The Exile of a China Hand: John Carter Vincent in Tangier

For the sin of accurately foreseeing the success of Mao Tse-tung’s communist insurgency, Foreign Service “China hands” were accused of disloyalty and punished.

BY GERALD LOFTUS

The cover of historian Gary May’s definitive biography of FSO John Carter Vincent, published in 1979.

New Republic Books

Mark Twain, traveling on one of the first American cruise ships, stopped in Tangier, Morocco, in 1867 and called on the American consul. “I would seriously recommend to the government of the United States,” he later wrote in The Innocents Abroad, “that when a man commits a crime so heinous that the law provides no adequate punishment for it, they make him consul general to Tangier.” The life of the lone American diplomat and his family in this North African outpost struck Twain as “the completest exile that I can conceive of.”

Almost a century later, Foreign Service Officer John Carter Vincent spent his last assignment (1951-1953) in a sort of political exile in Tangier’s International Zone, where a consortium of powers represented by diplomats from European and American legations governed what was a city-state prior to Morocco’s independence in 1956. Though never guilty of Twain’s “crime so heinous,” Vincent found himself caught in the vise of McCarthyism, which asked “Who lost China?” to communism. His offense: years of honest Foreign Service reporting from wartorn China.

In the offices of what had become the American legation in Tangier’s medina (walled city), Minister John Carter Vincent—whose other titles were diplomatic agent and consul general—was a world away from the previous focus of his diplomatic career. A member of what was called the “China Service” (the State Department’s corps of language-trained China experts), Vincent had spent much of the 1920s through the 1940s reporting from a country successively devastated by internecine fighting among warlords and invasion from Japan, then riven by civil war between nationalist and communist forces. In 1945 he was appointed director of the Office of Far Eastern Affairs, precursor to today’s assistant secretary of State for East Asia and Pacific affairs. He was the most senior “China hand” on active duty in the Foreign Service.

A self-described “New Deal liberal,” Vincent had come to see Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalists as hopelessly corrupt, and ineffective in prosecuting the war against the Japanese. Apart from the war effort, Vincent promoted a Chinese polity in classic “civil society” terms: support for human rights, democratization and the rule of law. But his no-nonsense criticism of Chiang and Madame Chiang—darlings of the American press and the powerful “China Lobby”—came back to haunt him once they retreated to the island of Taiwan (then called Formosa) and the communists took over the mainland in 1949.

For the sin of accurately foreseeing the success of Mao Tsetung’s communist insurgency, John Carter Vincent and other Foreign Service China hands were accused of having “lost China.” By the time Vincent settled into his new Tangier position, one of his colleagues, John Stewart Service, had already been dismissed from the Foreign Service. More ousters were to follow.

The Tangier Tangent

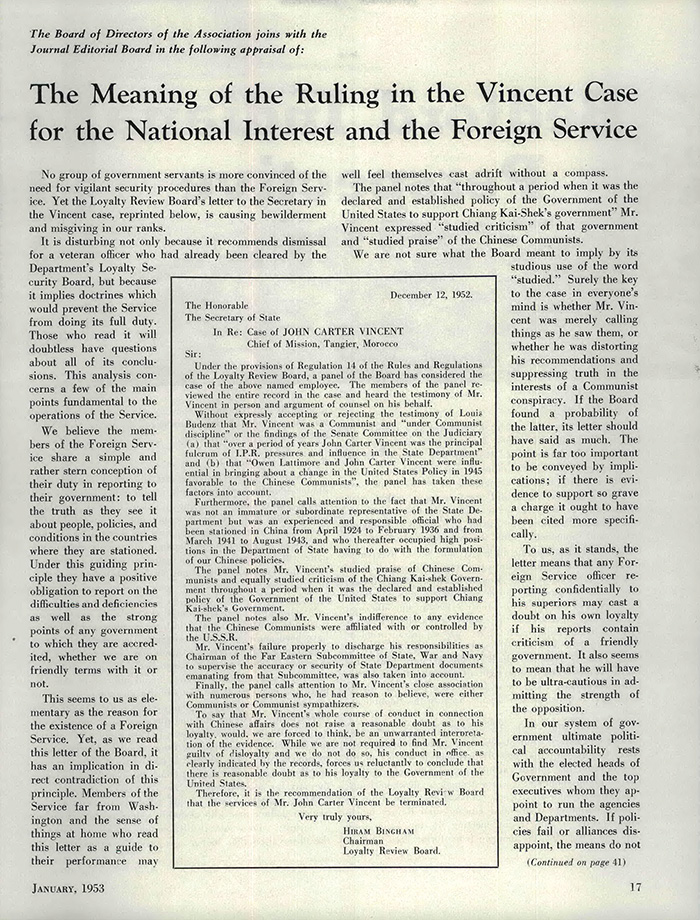

In January 1953, the FSJ Editorial Board published this appraisal of the ruling in the John Carter Vincent case. “It is disturbing not only because it recommends dismissal for a veteran officer who had already been cleared by the department’s Loyalty Security Board, but because it implies doctrines which would prevent the Service from doing its full duty,” the board states.

The Foreign Service Journal

Historian Gary May’s definitive biography of Vincent—China Scapegoat: The Diplomatic Ordeal of John Carter Vincent (New Republic Books, 1979)—describes how he ended up with a decidedly “out-of-area” Tangier assignment. By the spring of 1951, Vincent’s nomination as ambassador to Costa Rica was seen as doomed. Rather than pursuing that process, the State Department switched gears and sent him to Tangier because the position of chief of mission in a legation did not require Senate approval.

In a midnight phone call to Vincent, New York Herald Tribune correspondent Bert Andrews wondered why the veteran diplomat would accept such “a terrific comedown” (at the time, Vincent was chief of mission at the U.S. legation in Switzerland). Vincent, the product of a Baptist Sunday school education in Georgia, began his response by quoting a missionary hymn: “I’ll go where you want me to go, dear Lord.” He then continued, “I’ll take the Tangier appointment because I’m in no position to fight this thing financially.” Vincent had been under suspicion since 1947, and though he was to receive important moral support from The Foreign Service Journal and the American Foreign Service Association, AFSA had not yet established its Legal Defense Fund. (Vincent did receive the pro bono services of a team of experienced Washington lawyers.)

The new assignment did not end Vincent’s ordeal, however. His 22 months in Tangier were spent under the shadow of multiple investigations, requiring travel back to Washington no fewer than three times to testify before successive investigative bodies. During a particularly trying period where he remained alone in Tangier, he bitterly wrote to his wife, Betty: “This is the god-damnedest house to get lonesome in. ... There isn’t a thing in its curious roominess that I can get sentimental about. ... The place and the people are without meaning to me with you and the children gone.” Mark Twain would have commiserated.

Though not on the front line of the Cold War, Tangier nevertheless felt its imprint. Radio relay stations proliferated, several of which were American: RCA, Mackay and the Voice of America. With its strategic location on the Strait of Gibraltar separating Europe from Africa, Tangier had changed hands over the centuries between Moroccan, Portuguese, English, Spanish and, finally, international rule. The city was variously depicted in forgotten B-list films as a haven for spies, gangsters and general naughtiness. But its black market was real; whether in gold bullion or nylon stockings, the Tangier International Zone beat all records.

Under the headline “TANGIER: Nylon Sid & the Jolly Roger,” the Dec. 29, 1952, issue of Time magazine recounted the sensational story of a modern-day American pirate: nylon stocking trafficker Sidney Paley. The United States had jurisdiction over this “gentleman of the export business” who was charged with committing piracy on the open sea. While he did not personally preside over the trial in the legation’s Consular Court, John Carter Vincent must have found the proceedings a momentary distraction from his own woes, and perhaps even some comic relief: “Nylon Sid,” after his conviction, swore off piracy and told reporters that he would return to his original occupation—smuggling.

But the distraction was brief: Vincent learned that his own case was coming to an ominous juncture. On Dec. 12, 1952, the Loyalty Review Board wrote to the Secretary of State “In Re: Case of JOHN CARTER VINCENT, Chief of Mission, Tangier, Morocco,” recommending “that the services of Mr. John Carter Vincent be terminated.” Vincent was suspended, no longer cleared to read even his own telegrams. While observing a not-so-merry Christmas, he awaited further word from Washington.

Parallels with China

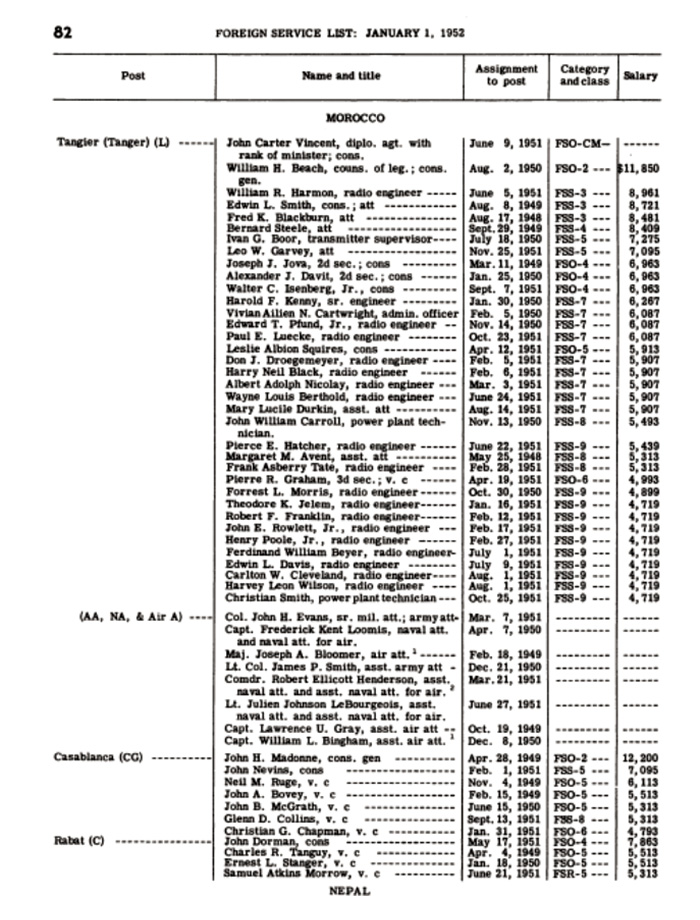

John Carter Vincent’s assignment to Tangier, as it appeared in the Foreign Service List of Jan. 1, 1952.

U.S. Department of State

Internationally administered Tangier was literally a world away from the China that Vincent knew well, but there were parallels. He had experienced China under various regimes— Japanese occupation, European Shanghai concessions, Nationalist- and communist-ruled regions and warlord territories—and found that Morocco had its own kaleidoscope of jurisdictions and interlocutors.

During the 1950s Morocco had emerged from the wartime occupation of Tangier by Francisco Franco’s Spain, which continued to hold the northern fifth of the country while France retained the rest. As minister of the legation and its diplomatic agent, John Carter Vincent was accredited not only to the International Zone, administered by Tangier’s “Committee of Control,” but was consul general in Morocco, which the United States recognized as part of a French protectorate with its administration in Rabat. While sympathetic to Moroccan aspirations, the United States was more attentive to French concerns. Paris hosted the headquarters of the new NATO alliance and provided valuable base rights in Morocco to the United States.

In a December 1952 first-person telegram, Vincent describes his call on the French resident general in Rabat. As in China, the main Moroccan political movements were nationalist and communist, referred to by Vincent as “the Istiqlal and Commie Parties,” both of which Paris had just outlawed. His use of “Commie” may have been simply the telegraphic shorthand in use at the time; but in view of the accusations against him boiling to a crescendo at that very moment, was it perhaps an attempt to burnish his anticommunist credentials? Legation political officer (and future ambassador to Mexico) Joseph Jova said of the McCarthy influence on his own drafting from Tangier: You “had to be careful. One would have been foolish not to watch what one was reporting, putting the proper caveats in to make sure it was an all-American point of view.”

Vincent’s China experience during the anti-foreign agitation of the 1920s was echoed in Tangier during the pro-independence riots in the spring of 1952. Troops were sent in from the Spanish zone and from the French protectorate, and American employees of the Voice of America relay station started to carry handguns in case they were caught up in the anti-European violence. For American writer Paul Bowles, a longtime resident of the city, “Tangier was never the same after the 30th of March 1952.” As in China a quarter century earlier, John Carter Vincent was witness to the beginning of the end of a colonial regime.

And in another area, a November 1952 dispatch, “Modifications in the International Regime of Tangier,” illustrated Vincent’s familiarity with the question of extraterritoriality. In China, the status of Americans through their treaty rights had been a constant source of tension with the Chinese authorities. The young, first-tour vice consul had organized the evacuation of hundreds of American citizens from provincial China when nationalist anarchy threatened those very protections, at one point shouting “American gunboat!” to disperse a threatening crowd.

A pensive John Carter Vincent on a return visit to Tangier in 1967, drawn by artist Marguerite McBey.

Marguerite McBey

The Last Post

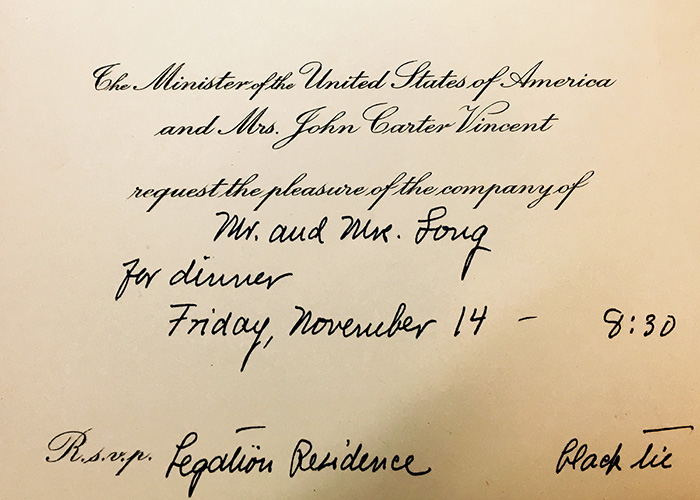

The invitation to a black-tie dinner hosted by Minister John Carter Vincent and Mrs. John Carter Vincent at the legation in Tangier.

Courtesy of Gerald Loftus

Despite his regular complaints, the record shows how attached Vincent became to what was to be his last post, even performing matchmaking duties there: a reception he hosted resulted in the marriage of another future American ambassador, Thomas Enders, to Gaetana Marchegiano, daughter of an Italian administrator of the International Zone.

There were occupational hazards to living in close quarters within the medina, however, as the April 12, 1952, New Yorker reported: “When the American minister entertains on his terrace, he is never quite sure if the neighboring housewives will not unintentionally bombard him with garbage or drape him with errant laundry.”

Vincent also joined in the revelry at the Tangier Press Club’s annual charity event, christened the “Pirates’ Ball,” featuring a caricature of “Nylon Sid” Paley, dressed in a bandana and sporting a cutlass. The guests were treated to a surprise appearance by a tuxedoed Paley himself. All very appropriate to Turbulent Tangier, the title of a 1956 book by Aleko Lilius chronicling the final years of the International Zone.

The outpouring of support for Vincent and his wife, Betty, after the world learned he had been suspended from his duties following the loyalty board’s announcement was recorded in a Dec. 26, 1952, New York Times article, “Tangier’s U.S. Colony at Vincent Farewell.” Lauding the Vincents’ support for the new American school and for the arts, the article notes the “indignation” of American expatriates, several of whom had “written protests to their congressmen” on Vincent’s behalf.

Political officer Joseph Jova sympathized with Vincent (“a very fine person”), but later opined that his wife should have been more circumspect instead of “sounding off,” which did not, perhaps, help her husband’s cause. The new Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, did revoke John Carter Vincent’s suspension in early 1953, but he was still forced to retire as of March 31. The Vincents departed Tangier, arriving back in the United States as private citizens on April 29, 1953.

In early 1967, a pensive John Carter Vincent returned to Morocco, where he was sketched by Marguerite McBey, an American artist who had settled in Tangier. McBey, who was selective in her invitations (“She’d reject duchesses if she thought they were boring,” wrote a friend), would likely have wanted to learn more about his persecution during the McCarthy era. Vincent’s trip down memory lane might well have included a visit to the old legation building, which by then housed the Foreign Service Institute’s Arabic language program for diplomats.

A few years later, Vincent had a chance to revisit a country he’d known since the beginning of his career: China. In the summer of 1971, during the excitement over President Richard Nixon’s announcement of his upcoming visit to China, a New York Times article mentioned that Premier Chou En-lai had invited the “China hands” back to Beijing. John S. Service accepted the offer immediately; but Vincent, touched by the Chinese Premier's invitation, wrote to his “Dear and Esteemed Friend” promising a visit “next year.”

That was not to be, however: John Carter Vincent, whose China policy recommendations were finally being acted on a quarter century later by Nixon (ironically, one of McCarthy’s congressional anticommunist cohorts), died on Dec. 3, 1972. At his funeral, he was remembered by a friend as “an old-fashioned Southern gentleman.” Today, he and the other victims of McCarthyism have largely been vindicated as upstanding truth tellers, while tormentors like Roy Cohn—McCarthy’s right-hand counsel— have had their hypocrisy and corruption unmasked.

The turmoil over “Who lost China?” was echoed in the 1980s, after the fall of another autocratic U.S. ally, the shah of Iran. Again, Foreign Service careers suffered. At the Foreign Service Institute, “Contacts With the Opposition” (the title of a Georgetown University symposium), a how-to on avoiding being misled into a regime-friendly mindset, became a theme in improving Foreign Service reporting from the field. This evolved during the 1990s, in places like Algeria, and informed approaches in dealing with the rise of “political Islam.”

Whether from China in the 1940s, Algeria in the 1990s or from somewhere else today, Foreign Service reporting can involve an element of danger—and not just because of local instability. As John Carter Vincent and the “China hands” learned to their cost, and as American diplomats continue to find, telling it like it is can be a high-risk occupation when Washington doesn’t like what it hears.

Read More...

- “The Meaning of the Ruling in the Vincent Case for the National Interest and the Foreign Service,” The Foreign Service Journal, January 1953

- “Memorandum by the Secretary of State in the Matter of John Carter Vincent,” The Foreign Service Journal, April 1953

- “China and the Foreign Service January 1952,” The Foreign Service Journal, March 1973