The Payne Fellowship: Boosting Diversity at USAID

Launched in 2012, the Payne Fellowship has proven itself a valuable program.

BY YOUSHEA BERRY

Payne Fellows gather at the National Press Club. Top row, from left: Mariela Medina Castellanos (2016), Tracey Lam (2014), Taylor Adams (2013), Ellexis Gurrola (2016) and Hoang Bui (2016). Bottom row: Suegatha Kai Rennie (2016), Jolisa Brooks (2016), Stephanie Ullrich (2016) and Brittany Thomas (2016).

Courtesy of the Payne Fellowship Program / Maraina Montgomery

The Donald M. Payne International Development Graduate Fellowship program was established in 2012 to attract outstanding emerging leaders from historically underrepresented backgrounds, as well as those with financial need, to international development careers in the USAID Foreign Service. With strong congressional support, the program is funded by USAID and administered by Howard University’s Ralph Bunche International Affairs Center. Since its inception, the Payne Fellowship has opened the door for qualified, educated and diverse young professionals to help USAID leverage their experiences as development professionals and diplomats. To date, 39 fellows have graduated and joined the USAID Foreign Service, and 20 more are currently completing the program.

At the same time, over the past few months, several news articles, letters to the USAID Administrator and a Government Accountability Office report have all pointed to the lack of diversity at USAID, particularly in senior leadership positions. Simultaneously, there have been several internal dialogues and “listening sessions” at USAID about implicit bias, institutional discrimination and racism. The civil protests and anti-racism efforts in the United States and around the world highlight the difficult balancing act that Foreign Service officers navigate in terms of the American ideals of freedom and equality, and the implementation of those ideals in the United States and abroad.

When coupled with other effective programs and initiatives, the Payne Fellowship is poised to help USAID address some of these issues.

An Effective Program

As an international affairs hub producing a pipeline of future U.S. diplomats, Howard University’s Bunche Center plays a critical role in administering the Payne Fellowship program. The Bunche Center is also home to two flagship State Department diversity programs, the Rangel and Pickering Fellowships. The reach of the center’s network and the prestige of these programs ensure a competitive pool of applicants for the Payne Fellowship annually.

The diversity of program participants is central to its success: 86 percent are from underrepresented ethnic and racial backgrounds— primarily Black (34 percent), Hispanic (25 percent) and Asian (19 percent). In addition to ethnic and racial diversity, the fellows come from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds and must demonstrate financial need. They also represent a wide array of undergraduate institutions and academic disciplines. Many fellows have worked in the private sector or in nonprofits and advocacy programs. A significant number have served in the Peace Corps, AmeriCorps and Fulbright programs, proving their dedication to public service and international causes.

After successfully navigating a highly competitive process, Payne Fellows commit to serve a minimum of five years in the USAID Foreign Service, with the anticipation that they will remain with the agency after their formal fellowship commitment ends. The fellowship provides support for a master’s degree, including tuition, fees, living expenses and two 10-week internships during the summer: the first on Capitol Hill and the second at a USAID mission overseas. One of the key features of the program is mentoring. Payne Fellows are promptly paired with seasoned USAID mentors to help them enhance their skills and knowledge while gaining an early understanding of the values and mission of the agency.

A 2015 Payne Fellow, Keisha Herbert, learned about the fellowship while she was living in an indigenous village in Guatemala as a Peace Corps volunteer. Her Peace Corps service and her work as a diversity and inclusion training and programs specialist in a U.S. public hospital sharpened the skill set she would later employ as a new FSO, which included fluency in Spanish, an understanding of cross-cultural competency, and recognition of the importance of diversity and inclusion. Herbert now serves as a program officer at USAID/Jordan.

Jacqueline Rojas, a 2017 Payne Fellow, says: “In my short time as a USAID Foreign Service officer, I’ve witnessed policymaking, diplomacy and the effects of U.S. foreign assistance in action. Thanks to my graduate education and experiences through the Payne Fellowship, I have felt equipped to handle whatever challenge comes my way—whether it be working to develop a resource to help agency staff improve their private sector engagement efforts through collaborating, learning and adapting or helping a USAID mission design its new country development cooperation strategy.”

Rojas explains that supportive team members and access to the fellowship’s mentors have been crucial to her ability to navigate her early career as an FSO.

The Payne Fellowship has strong congressional backing. More than 40 members of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate actively support its funding and growth through the annual appropriations bills that fund USAID. In a joint letter to the House State and Foreign Operations Appropriations Subcommittee, for example, the late Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), Rep. Alcee Hastings (D-Fla.) and Rep. Gregory Meeks (D-N.Y.) requested increased FY 2020 funding for USAID to honor the legacy of Rep. Payne and “his lifelong efforts to increase diversity in international affairs and support foreign policy and assistance strategies that are inclusive of diverse and underserved populations.”

Payne Fellows from the 2015 cohort strike a pose. From left: Jeanne Choquehuanca, Keisha Herbert, Berhan Hagos, Lea Claye and Marvin Crespin-Gamez.

Courtesy of the Payne Fellowship Program

Challenges Persist

The Government Accountability Office’s June report on USAID, “Mixed Progress in Increasing Diversity, and Actions Needed to Consistently Meet EEO Requirements,” showed that the overall proportion of racial or ethnic minorities in USAID’s full-time, permanent, career workforce increased from 33 to 37 percent from 2002 to 2018, but that the direction of change for specific groups varied: For instance, the proportion of Hispanics rose from 3 to 6 percent, while the proportion of African Americans in full-time, permanent, career positions fell from 26 to 21 percent, and the proportion of racial or ethnic minorities was generally smaller in higher ranks.

The gaps and potential barriers that GAO identifies directly mirror and affect the experience of Payne Fellowship alumni who are in the early stages of their USAID careers. “Now as a first-tour officer with USAID … I am the only African American in the USAID post here in Jordan, and the total number of USAID officers who are people of color is around five,” Keisha Herbert observes. “The current racial tensions in the U.S. have put the spotlight back on diversity and inclusion, and embassies around the world are feeling the pressure to diversify recruitment and better represent the demographics of the U.S. abroad.”

For her part, Herbert is seizing the opportunity to contribute and lead on efforts to increase diversity and inclusion at the embassy: “I’m helping to lead this mandate ... here in Amman and have received genuine support, guidance and buy-in from senior leadership. I’m not sure how long it’ll take for the diplomatic corps to completely reflect the diversity of the U.S. throughout its ranks, but the conversation is starting, and I hope the momentum continues to build and achieve the goal.” The Payne Fellowship’s contribution to this effort cannot be overstated.

Take, for instance, Chigozie Okwu, a 2017 Payne Fellow. While he values the opportunity to serve at USAID, he candidly reflects on how the presence of Black mentors and, conversely, the lack of other Black faces at internal and external meetings, bear on his experience as an environment officer. “During my time, there have been many other Black development professionals who have supported and championed my success and place at USAID. These strangers helped create a more welcoming environment for me by providing tips to help me navigate the federal bureaucracy or sharing experiences about life at USAID,” he says. “However, I am acutely aware of, sometimes, being the only Black person in the room, and people always make sure to emphasize that I am ‘articulate’.” Okwu observes that there are not many midcareer Black environment officers at the agency, and it is often difficult to fully discuss how micro- and macro-aggressions in the workplace affect his experience. He notes that, despite these challenges, “I do believe that I am extremely fortunate to have this career and have to find a balance between all the aspects of working for USAID.”

Several USAID FSOs who entered the agency through the Payne Fellowship program report that they have endured stigmatizing and condescending comments by other agency staff who assume that the Payne Fellowship gives fellows an unmerited “free pass” into the agency. In fact, the reverse is true—the vetting and application process for Payne Fellows is extremely rigorous and competitive. “The number of applicants for the Payne Fellowship has steadily increased throughout the years while maintaining a high concentration of underrepresented talent in the applicant pool,” states Payne Fellowship Program Director Maria Elena Vivas-House. “Applicants come from virtually every state and even some U.S. territories and attend hundreds of undergraduate institutions.”

Educating others about the Payne Fellowship program may help reduce the apparent stigma that former Payne Fellows have identified. In a July 2020 internal USAID newsletter, “Frontlines,” USAID Counselor Chris Milligan addressed the issue. “The Payne program enables the agency to attract top-notch talent. It also strengthens our core value of diversity by encouraging the application of members of historically underrepresented groups in the Foreign Service, as well as those with financial need,” he wrote. “Obtaining a Payne Fellowship is extremely competitive; more than 500 impressive candidates applied for the 10 positions available this year. As a comparison, the acceptance rate for a typical Foreign Service position is 4 percent—which means the Payne Fellowship is at least twice as competitive. Candidates for the Payne Fellowship undergo a rigorous selection process; a panel of interviewers review each candidate’s experience and career objectives, grades and writing skills, language(s) and potential to represent our agency.”

2019 Payne Fellows at AFSA with Representative Donald M. Payne Jr. From left: Rose Quispe, Bemnet Tesfaye, Michelle Ngirbabul, Natalie Fiszer, Susan Ojukwu, Jessica Hernandez, Rep. Donald Payne Jr., Niesha Ford, Meklit Gebru, Marianna Smith and Avani Mooljee.

Courtesy of the Payne Fellowship Program

Next Steps

The Payne Fellowship will increase from 10 to 15 officers in 2021. That’s not enough. By comparison, the Rangel and Pickering Fellowships bring in 90 fellows annually, and the programs are expanding for 2021.

Further, though the composition of the fellowship cohorts has been ethnically diverse, it has been predominantly female—only one Black male has completed the program since its inception. To ensure broader gender representation, increase professional development opportunities, and expand the recruitment and retention of stellar, diverse talent, the program has deepened its relationship with two key partners. They are USAID’s Development Diplomats in Residence—with one diplomat recently serving at Morehouse College, an all-male Historically Black College and University in Atlanta—and the USAID-based alumni of the International Career Advancement Program. Members of the latter formed a Payne Advisory Group more than a year ago to help identify opportunities to improve “the felt experience” of the fellows once they join the agency.

The advisory group meets regularly with staff of USAID’s Bureau of Human Capital and Talent Management to elevate concerns and help expedite solutions within the agency. For example, when the summer placements at missions and in congressional offices were canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Payne Advisory Group identified a diverse cohort of USAID leaders to serve as situational mentors, launched a “virtual office hours” series for off-the-record conversations with agency leaders, and hosted “virtual coffee chats and meet-and-greets” with leaders of USAID employee resource groups and other USAID networks. Ultimately, the increased coordination among HCTM, the Foreign Service Center, DDIRs, Payne Advisory Group representatives and Payne program staff at Howard University has led to better transitions for Payne Fellows into the program and agency during this extremely uncertain time.

Since the program is new, retention data is limited. Fellows who have completed the program are current FSOs. Only a handful have met the tenure requirement, and they are still with USAID. The return on investment for the Payne Fellows’ graduate school education and professional development is high, and the U.S. government and USAID’s partners around the world benefit when they see America’s diversity represented abroad. Fellows also benefit directly from and value this experience.

Yet there is a continued need for broader recruitment and retention efforts beyond the Payne Fellows program, particularly given the limited number of fellowships available each year. There is also a concern that it is easier for agency leaders to focus on recruitment rather than working to resolve retention issues around promotion and tenure for minority FSOs. USAID must ultimately ensure that all managers are held accountable for their efforts in hiring, retaining, empowering and promoting qualified individuals from underrepresented groups.

There is a growing call across our nation, and from within USAID, to address the effects of institutional racism. In this regard, it is appropriate to pause and reflect on Rep. Payne’s legacy. Not only did he put his life at risk in Mogadishu in 2009, while advocating for democracy and human rights, he never stopped fighting for equality and fairness for all Americans. Neither should we.

The Program’s Namesake: Rep. Donald M. Payne Sr.

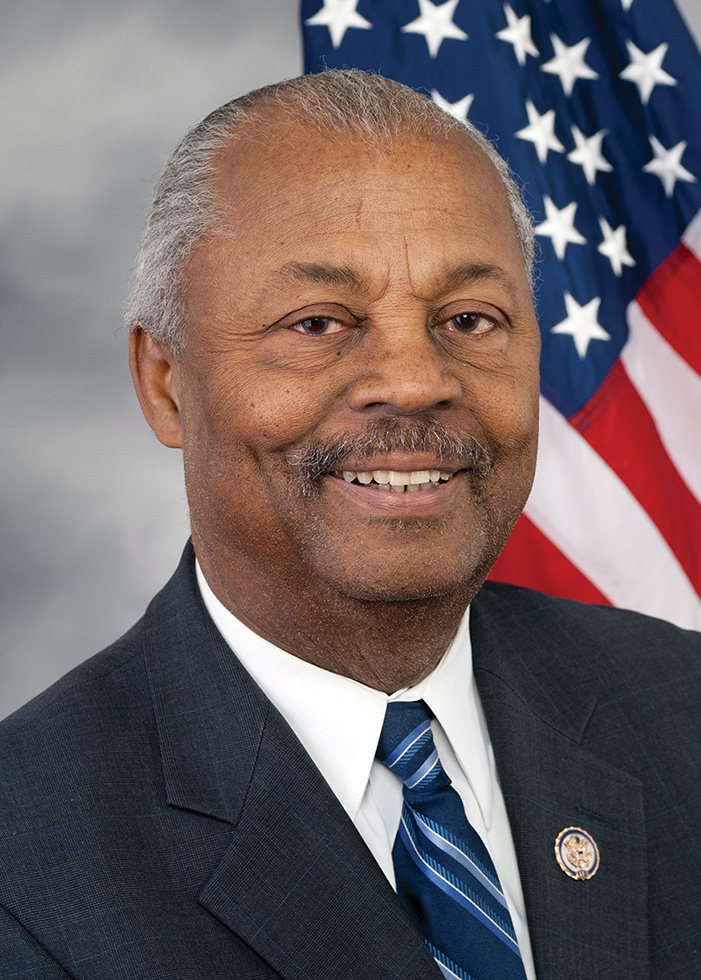

Rep. Donald M. Payne Sr.

In 2009, the late Congressman Donald M. Payne Sr. (D-N.J.) traveled to Somalia to engage in strategic dialogue and to witness firsthand the social, economic, security and political challenges facing the wartorn country. As he departed Mogadishu airport, an Islamist insurgent group based in East Africa, al-Shabaab, bombarded his plane with mortars. Shortly thereafter, Rep. Payne, a longtime champion of USAID, spoke passionately before Congress about the need to build the capacity of the Somali people by investing in their unity government. He urged that technical assistance and financial support be provided so Somalia could progress and lead the regional fight against terrorism and piracy.

Members of Congress on both sides of the aisle respected Rep. Payne and frequently looked to him for leadership on global development issues. His legislative record was expansive and historic, including brokering the major trade agreement with the continent of Africa—the African Growth and Opportunity Act—and crafting legislation to authorize the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the President’s Malaria Initiative.

Moreover, he vocally and presciently declared the systematic murder of people in Darfur a genocide and was recognized in Congress for having the most supportive record on issues regarding the Northern Ireland peace process. President George W. Bush twice appointed Rep. Payne to serve as a congressional delegate to the United Nations.

Congressman Payne tirelessly fought for the advancement of international cooperation and development, particularly in Africa and the Western Hemisphere for decades prior to his death in 2012. When USAID administrator Rajiv Shah launched a new junior Foreign Service fellowship program later that year, it was fittingly named after Rep. Payne.

Aysha House, a former congressional staffer who now serves as senior adviser and interagency coordinator for the Bureau for Resilience and Food Security at USAID, said of Rep. Payne: “I was proud to be in the presence of someone who believed so deeply in the power of international development. From combatting the pressing global challenges of poverty and hunger, violence and piracy, injustice and accountability in government to access to education and so much more, Rep. Payne was our steadfast champion.”

Ms. House and career FSO Lorraine Sherman, both of whom were working in the Bureau for Legislative and Public Affairs at the time, played a significant role in establishing the Payne Fellowship program.

Read More...

- “State Department expands diversity fellowships amid pressure to better support diplomats of color,” by Conor Finnegan, ABC News, September 1, 2020

- “Fighting for U.S. Values Abroad, Black Diplomats Struggle With Challenges at Home,” Robbie Gramer, Foreign Policy, June 11, 2020

- “A Reckoning With Race to Ensure Diversity for America’s Face Abroad,” Lara Jakes, The New York Times, June 27, 2020