What We’re Doing Now

We began preparing this issue of The Journal in January, with a broadcast message to retired and former members of the Foreign Service requesting input on the “afterlife.” We asked members to reflect on what they wished they had known earlier about retirement and what advice they would give their younger selves on planning for it. We asked what they wish they had known before joining the Foreign Service. And we asked them to tell us about their interesting post-FS lives, including advice for others who may want to take a similar path.

The response was quick and abundant. We received more than 45 thoughtful essays—far too many to publish in one month, so we have included some here and will feature the rest in an upcoming issue.

We thank all those who took the time to write. As you will see, these fascinating commentaries are testimony to the great variety of meaningful paths open to individuals who have made a career in the Foreign Service.

Whether you just joined the Service, are paddling along at mid-level, or negotiating the senior threshold—you are sure to find these stories inspiring and insightful. Enjoy!

—The Editors

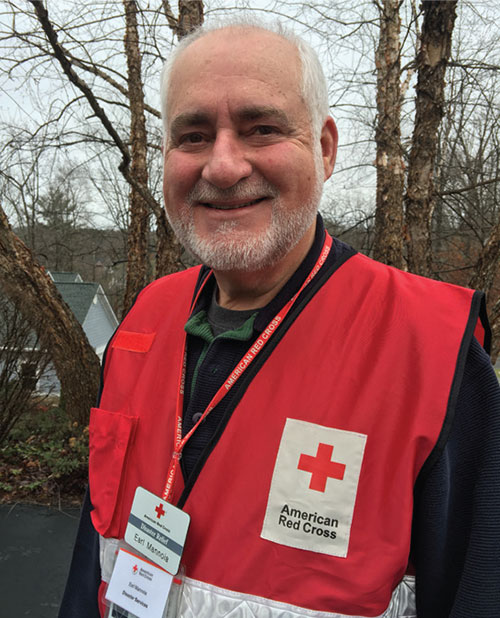

Volunteering for Disaster Response

BY EARL MANNOIA

Earl Mannoia

Courtesy of Earl Mannoia

After retiring in 2000, I was still doing work for the State Department four years later when my wife, Breda, and I began doing volunteer work for the American Red Cross. We were fascinated by the work, and felt it would provide us with the challenges and opportunities we wanted in retirement.

We were living in our new home at Smith Mountain Lake in Virginia. Within six months we were the Disaster Action Team leaders for our county. In that capacity we responded primarily to house fires and provided families with their first assistance in the form of housing and money for clothing.

Our first national disaster response was Hurricane Katrina. We served two three-week tours in Mississippi, where we had some of the most challenging and rewarding experiences of our lives. We were hooked. We are both in Red Cross leadership positions now and have responded to many national disasters. I am on the Virginia state leadership team and have responsibility for Red Cross government liaisons statewide.

Breda also volunteers at the local American Cancer Society thrift shop, and I do a fundraising golf tournament for the Red Cross each year. We are both involved in other activities such as golf, gardening, jewelry making, motorcycling, singing in a barbershop chorus; but it is the Red Cross that gives us a sense of accomplishment and purpose.

I feel like I’m having a second career that is as satisfying as my time in the Foreign Service.

From Consular Officer to Immigration Attorney

BY RUSS WINGE

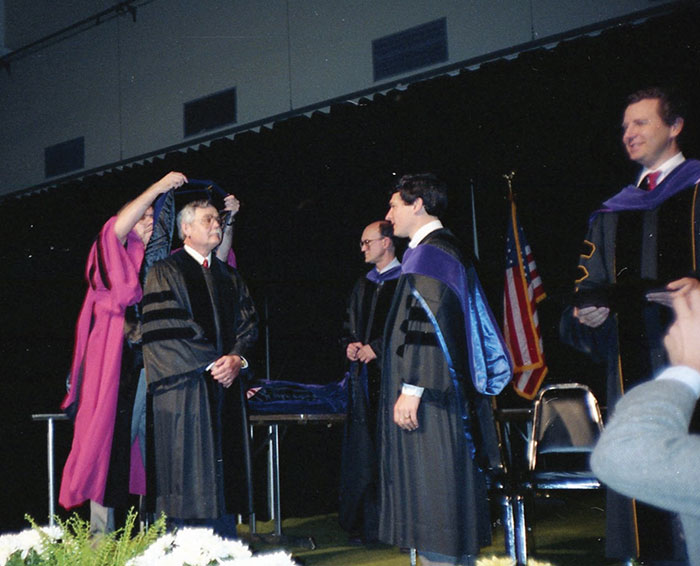

Russ Winge at his graduation, Senior Citizen Class of ’88, from Lewis and Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon.

Courtesy of Russ Winge

I welcome the opportunity to share my story of life after the Foreign Service. I chose the consular cone and during my career concentrated on learning as much as I could about immigration law because I believed it offered a skill set that would be most easily marketable upon retirement.

While assigned to Vancouver, I had personal contact with many immigration attorneys. When word got out that I would soon retire, I received several offers to work at law firms as a legal assistant. I realized I knew as much or more about immigration law as most attorneys.

I then began considering law school. First I needed to know if I could get into one, so I took the law school admissions test (LSAT) and applied to three law schools in the Northwest. To my surprise, all three welcomed me!

After some in-depth planning with my wife, Aileen, we decided to go for it, and I retired. At my retirement luncheon in Vancouver, a young vice consul asked me if I thought I might be a bit old to be going to law school. I told him, perhaps, but I would give it a shot, practice law for a while, and if I didn’t like it, I might try medicine!

I matriculated at Lewis and Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon. While I studied, Aileen worked for the Immigration and Naturalization Service in Portland. She had taken all the correspondence courses offered by State and by INS, and she was a most welcome employee.

After I graduated, I set up a law practice and Aileen came to work with me. Her work at INS made my future presence there as an attorney presenting cases much smoother. Furthermore, her in-depth knowledge of INS and State Department requirements and procedures was instrumental in guiding clients through the process.

My law practice was very successful. I managed to earn far more than I could have earned at the highest levels of State, and was able to put my children through university debt-free and meet all the other financial goals I had set. I eventually sold my practice and retired debtand mortgage-free to a lovely home on the Fall River in Oregon.

I truly enjoyed my Foreign Service career and my law practice. In full retirement, I now enjoy fly fishing, club chess and learning to fly on my highly sophisticated flight simulator. My wife approves of the latter activity in lieu of real flying because the worst that can happen to me would be to fall out of my chair!

To consular officers, I say: there is a use for your skills in retirement if you are willing to make the effort. It is the visa function, in particular, that offers opportunities in retirement either as a legal assistant or as an attorney.

To those of you who play the “I’m too old” card, I assure you that you are not. Law school was time-consuming but not difficult. I treated the experience as a full-time, eight-hour-a-day job, complete with coffee and lunch breaks. When not in class, I was in the library. As a result, I was able to spend evenings and weekends with my family. I am proud of my “second effort,” and I tell you this—if I could do it, so can you.

Best regards to my retired Foreign Service friends.

Network and Cultivate Mentors

BY CAMERON MUNTER

Just as it’s important to have mentors during your Foreign Service career, it’s important to have them for the afterlife. I noted that many colleagues in the retirement course seemed oddly puzzled, kind of bereft, when they realized they were leaving a system in which, for decades, they’d known to whom they should turn.

Don’t fall into this trap. You’re still part of a network if you choose to be. Who did you admire when you were an officer? That consul general or deputy chief of mission is probably working out in the real world somewhere and can give you good advice.

In my case, I went to a venerable Foreign Service legend who lives in New York. He said: You have three choices. You can get a job somewhere in business. With any luck you’ll make good money, work very hard. Option two: You can buy white shoes and move to Florida and learn to golf.

Option three (clearly the right answer, as far as he was concerned; don’t forget, we’ve all written action memos presenting a principal three options): You can build a “portfolio retirement,” in which you have a base and can expand your work from there as you wish.

In this third option, for example, you can be an adjunct professor or a leader of a nongovernmental organization (NGO) or do some other job that probably won’t make you enormously wealthy but will bring satisfaction and an office where you can display your tokens of appreciation from the Karachi Chamber of Commerce.

These jobs, he said, are easier to swing the farther you are from Washington, D.C. Then consult based on your Foreign Service expertise, spending as much time consulting as you wish based on your need for money or the time available. That means your public life need not end suddenly but can continue as long as you want it to.

I took adjunct professor jobs (actually, “professor of practice” positions), first at Columbia Law School and then at Pomona College; I joined the Washington consulting firm Albright Stonebridge, as well as a couple of London-based investment firms. And I had the pleasure of working on such projects as polio eradication in Pakistan (with the Gates Foundation), private telecommunications development in the Balkans (with KKR), and even various attempts to settle the longstanding Budweiser trademark dispute (between the government of the Czech Republic and InBev, the owner of Anheuser-Busch).

After doing this for a couple of years, I ended up taking the position of president and CEO of the East West Institute in New York, going back to a single job, but one engaging diplomatic skills in international conflict prevention.

As for what I wish I had known before I joined the Foreign Service: I wish I’d studied dramatic arts. Sure, it’s nice to be conversant with international relations, history, literature and economics. But it’s even more important to learn, as early as possible, about how to play your part, demonstrate sincerity on stage and understand the roles that others play.

Becoming a Minister, According to Plan

BY LOIS AROIAN

Lois Aroian in the First Presbyterian Church fellowship hall after her installation.

Courtesy of Lois Aroian

My “retirement” has been a journey into joy. My plan had been to retire at age 65, but circumstances intervened. While serving as consul general in Quebec City in 2000, I led worship occasionally at local English-speaking churches. A friend suggested I go to seminary and become the pastor at her church.

Three years later, while serving in Washington, D.C., I parachuted into a local seminary I’d never even visited. One course at a time, I became a candidate for ministry in the Presbyterian Church, USA (PCUSA).

That meant that when I retired in 2007 after a 23-year career that included tours as deputy chief of mission in Mauritania and Botswana, my progress toward my next career as a Presbyterian minister was already well underway.

While enrolled at Wesley Theological Seminary in D.C. following my retirement from State, I went to work in the declassification office that scans volumes of the prospective Foreign Relations of the United States after the books are compiled by the Historian’s Office. What a wonderful job, linked to my pre- Foreign Service training as a Middle East historian and author! I loved reviewing historical documents from presidential libraries and new FRUS volumes.

The higher income also gave me an opportunity to volunteer as an evaluator for the Future Leaders Exchange program bringing high school students from former Soviet republics to the United States. I could have stayed in that office forever, as most people who work there do.

However, in 2010 I accepted a call as pastor of a small church in rural Willow Lake, South Dakota, on a PCUSA program to match recent seminary graduates with rural churches.

Our Presbytery appointed me immediately to the Synod committees on racial-ethnic ministry and self-development of peoples. This broader engagement led me to attend the PCUSA General Assembly in Detroit in 2014, as well as the upcoming 2016 GA in Portland, Oregon.

In November 2015, I was called as pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in East Jordan, Michigan. I told the committee that my long-term plan was to retire at 80, as my dad had done. I feel very blessed that this wonderful congregation was willing to take a chance on someone well past the usual retirement age.

Ever since surviving meningococcal meningitis in my 20s while doing my doctoral research in Egypt, I have felt the importance of making each day count and of helping others.

I have no regrets. I went to college at age 16 planning to become a Presbyterian minister.

Two Truths

BY MARC E. NICHOLSON

I retired fairly early and with no financial worries, so my comments relate to the social side of life. I “sort of” knew two truths when I retired, but they became more vivid over time.

First, in middle age our friendships and social life are overwhelmingly obtained through our work life, so when one leaves the job, the room can become very quiet very soon unless one develops other associations and organizational affiliations that put one in contact with other people. And that human contact is essential to mental health and happiness.

Second, while at first in retirement we want to “clean up” various projects that had been postponed, it is important to shift soon if one has an aspiration to acquire a new talent or skill or one has a new career ambition. The longer you postpone it, the more you will feel that it’s too late in life to pursue it and reap sufficient benefit from your efforts. I was tempted on retirement to learn to play classical piano, but did not, and now regret that it may be too late.

Mr. Mayor: Still Keeping Promises Three Terms On

BY JIM CASON

Jim Cason (at right), the mayor of Coral Gables, Florida, presents the “Key to the City” to Jose Soria, Spain’s minister of commerce.

Courtesy of Jim Cason

Little did I imagine as I boarded the plane in Asuncion at the conclusion of my three-year stint as U.S. ambassador that I would end up as the mayor of Coral Gables, one of America’s most beautiful small cities.

My plan was to take the retirement seminar and move to Florida to begin a life of leisure after 38 years with State. The seminar suggested many ways to keep busy, but running for local office was not on the menu. I thought I might do some part-time work as a consultant after getting settled in a new home.

My wife and I had long had our eyes on Coral Gables as an ideal retirement community. Located just south of Miami, the “City Beautiful” of 47,000 residents is home to the University of Miami, many consulates and trade offices, and some 135 Latin American corporate headquarters. It was planned in the 1920s by George Merrick, who envisioned creating an international theme city from 3,000 acres of pine trees and fruit orchards.

Today it is renowned for its tropical foliage, well-kept homes, cultural attractions, and the linguistic and ethnic diversity of its inhabitants, most of whom have university degrees. USA Today and Rand McNally have named Coral Gables the second most beautiful small town in America.

The city is 58 percent Hispanic, a majority Cuban-American. I spent most of my career in Latin America, and served as chief of mission in Havana from 2002 to 2005. I realized that many people knew of me from Havana, where I had a reputation of creatively working with the opposition movement. Cuban-Americans began urging me to run for state or county office. However, I was more interested in getting acclimated and developing a circle of friends.

By mid-2009, some 18 months after moving to Coral Gables, I began to grow restless. The State Department Office of the Inspector General invited me to become a senior inspector, and I took assignments in Amman and Baghdad. But as I settled into my new city, I began to realize that Coral Gables voters were looking for new leadership. After months of delving into city records and talking with the manager, I decided to make a run for mayor. The odds were very much against a complete newcomer, but I won.

There is a role for diplomacy in municipal government. Being mayor requires empathy and good listening skills, as citizens bring their problems to me for resolution. Given the breadth and depth of my Foreign Service experience, I could see options for solutions that others may not have considered. Running a commission requires tact and courtesy, compromise and, at times, firmness. And as the city’s ambassador, I get out to meet my constituents, explain what we are trying to do and seek support and understanding of the financial constraints facing the municipality. Above all, I am accessible and available to all who want to see me.

Taking office, I promised to be a full-time mayor, to tackle pension reform and to lower the tax millage rate. Three terms later, I continue to keep those promises.

While most FSOs won’t have the advantage of the support base that I had, you can win a local election. I think many smaller communities would welcome the fresh perspective we bring, our linguistic and public speaking skills, our ability to understand others’ views, and our flexibility and management experience.

Take a chance; reinvent yourself, and have fun!

Thinking about What’s Next

BY TED CURRAN

A key bit of advice for Foreign Service employees planning for retirement is to begin thinking about post-service life opportunities well before you leave the Service. The following questions should be posted on your “What’s Next?” chart.

• Are there institutions you have worked with in the Foreign Service such as think tanks, educational institutions or U.S. businesses with offices abroad with whom you have had contact? (These are excellent resources for job opportunities.)

• During your time in the Service did you pick up a language at level 3 or above that would be helpful to colleges or businesses located overseas? (It is still remarkable how few employees in China or Latin America speak the local language with any facility.)

• If married, does your spouse have language or personal ties that both of you can use as entry points for jobs? (The Ford Foundation, for example.)

Increasingly, U.S. colleges and universities are promoting study in the United States. These institutions are looking for “counselors” to find and support students from abroad. Assuming that FSOs are retiring to university towns, there are (paid) opportunities to be involved in the foreign student programs.

Seek an interview with a professional search firm. Their staffs are usually good, and there’s no charge!

Keeping Wild Equines Safe and Free

BY CHARLOTTE ROE

Mustang mare Carmelita has a conversation with Charlotte Roe shortly after her adoption. Carmelita is saying: “I’m still getting over the roundup and being separated from my band. … Will you be my forever family?”

Riley Salyards

Going from FSO to wild equine caretaker and advocate wasn’t my plan. I’d grown up riding and had livestock on a small ranch in Ohio, but thought I’d left that part of my life behind when I entered the Foreign Service.

As intended, immediately after retirement I moved to Colorado, where my three sisters live in the mountains, and where I’d done my undergraduate studies. I became active in the Colorado Celtic Harp Society and combined my part-time music career with the ancient art of storytelling. I got involved in Spellbinders, a national organization that trains volunteers to tell stories in public schools and libraries, and I joined Northern Colorado Storytellers. Telling animal stories from all corners of the globe to children and adults is a great way to spur learning and pass on traditional knowledge. My specialty is bilingual story-weaving in Spanish, which my husband, Hector, and I speak at home.

Our first home in Colorado had a barn, an irrigation well and an acre of pasture. We thought about getting goats to mow the field. Instead, because of our two large dogs, we chose donkeys. These highly intelligent animals don’t run away or panic when faced with would-be predators. They stand guard and assess the situation. We discovered Longhopes, the only globally sanctioned donkey shelter in the United States, and adopted a mother-daughter burro pair that had come from a wild herd range in the Sonoran Desert. Later Longhopes offered us a young gelding they had acquired from a local “kill pen” run by brokers who buy up unwanted equines and sell them for slaughter in Mexico and Canada. The three won our hearts with their alert ears, soft eyes and savvy ways.

One thing led to another. We moved to a five-acre, semiabandoned farm and began barn-building and restoring and fencing pastures. It was then that an older Andalusian-Appaloosa who needed a home galloped into my life. A powerful steed with a dominant attitude, he challenged me to begin retraining in natural horsemanship. Next we adopted a young “wild” mustang mare from Oregon who had been a star performer in an Extreme Mustang Makeover competition in Loveland, Colorado.

Then something big happened. My husband and I doubled up on riding to keep both horses in shape. The mustang and her burro friends breathed fire into me. What had previously seemed a romantic, somewhat remote quest—the fight to keep wild horses and burros safe and free on their native lands in the West—had come home. I delved deeper into the situation. In 1971 Congress unanimously passed the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act to protect these free-roaming creatures that were being slaughtered for the pet food industry. Today, they are still threatened.

This is not an issue that lends itself to simple solutions. The question of who benefits from our public lands is fraught with conflict, deception and misunderstanding. I have reached out to scientists and specialists in wildlife biology, wildlife fertility control and animal ethics. I connected with national and grassroots organizations. I’m publishing articles and op-eds and interpreting the story of Velma “Wild Horse Annie” Johnston, one of America’s greatest unsung heroines. I joined the Board of Longhopes Donkey Shelter and recently became an adviser to The Cloud Foundation, which works to preserve wild horses and burros on our public lands. With other horse and burro fans and adopters, I founded a network called the “Wild Equid League of Colorado” to promote education and informed action on this issue.

My advice for those considering retirement is this: Don’t over plan. Get engaged, because those who run the world are those who show up and roll up their sleeves. Everything you learned and applied in the Foreign Service will come into play. Albert Einstein said it well: “Those who have the privilege to know have the duty to act.”

Setting Sail: A New World of Challenges and Adventures

BY EDMUND HULL

Retired FSO Edmund Hull aboard S/V Panope in Gibraltar after his 2011 transatlantic passage.

Courtesy of Edmund Hull

I abbreviated my Foreign Service career at age 55. Three factors influenced that decision. First, in 2004, any future path for an Arabic-speaker led through Iraq and, like many in the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, I saw our invasion as a mistake fraught with tragic choices. Second, I had an excellent academic job waiting that would last at least a year. Third, I had long wanted to sail seriously, and I thought best to undertake that challenge physically fit.

On occasion, I regretted my choice. I saw colleagues pursue more fulfilling diplomatic careers despite or because of their Iraq service. Good friends assumed leading roles in the State Department, and I calculated that I would have fared well in the “D” committee. In retrospect, I felt that I left a lot of power and prestige on the table.

My compensation was great, however, because after two years of teaching, I did, indeed, embark upon a true adventure that would have been difficult, if not impossible, in later life. I bought a sailboat and with it a new world of challenge.

My experience was not that of the boating magazines— smooth sailing under blue skies in crystal clear tropical waters. The first couple years on the Chesapeake Bay were dedicated, literally, to learning the ropes—how to set sails, including big head sails like a gennaker; and, more importantly, how to douse them when a sudden thunderstorm leaves you seriously overcanvassed on a boat veering out of control. Even more challenging, for a policy wonk like me, was learning how to keep a diesel engine operating reliably. Both physically and intellectually, I was well out of my comfort zone.

In 2008, after a couple of years of making mistakes on the Bay, I decided to try an offshore passage to Bermuda, then on to Maine. With me was Len Hawley, an experienced sailor, with whom I had worked on peacekeeping and counterterrorism at State. We made it half way before head winds, fuel shortage and a fresh water leak dictated a new strategy. We hove to for two days waiting for a weather break so we could recross the Gulf Stream, and then headed northwest to Montauk. With little fuel, our sailing skills were severely tested over the next three days. In the Montauk channel, our starved engine actually sputtered before a slight grounding pushed the last bit of fuel from the tank and into the engine.

I would subsequently make Casco Bay in Maine, Bermuda on my second try, the Bahamas a couple years later, then Bermuda-Azores-Gibraltar. In 2011, the western Mediterranean; and, finally, in 2014, the eastern Med to our second home in Cyprus. The challenges from weather, waves, navigation, cooking, heads, coral reefs and more were constant and varied. Costs also added up: I stopped calculating in dollars, and adopted “boat units” ($1,000) as currency.

What rewards could justify the costs?

First, the satisfaction of following a challenging career with a challenging retirement. Declining the safe and comfortable in favor of calculated risk and mastering, or at least surviving, elemental nature and ever-changing problems with sails, lines, engines and electronics. Second, my passages offered opportunities to former State colleagues, family members and friends. That crew not only enabled my passages, but also created a camaraderie that substituted well for the rush of a country team in crisis.

Finding the Perfect Retirement Work

BY SONNY LOW

Sonny Low found his ideal retirement job working in the Gardening Department at Home Depot.

Courtesy of Sonny Low

Retirement started for us on July 5, 2005, when we boarded a flight to London to start a “Grand European Tour” for three weeks. The tour took us from England to France, Monaco, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Germany and back to Washington, D.C.

Fully decompressed, my wife, Mirian, and I boarded Amtrak for our cross-country trip. On Aug. 1 we arrived at my hometown where, after a 10-day visit with my sister’s and brother’s families, we packed up our sturdy Honda CRV for the 1,200-mile drive down to Chula Vista, California, to start this newest adventure in our lives.

Long before retirement, the frigid winters and humid summers of Washington, D.C., were important in our decision to move west. Moreover, the prospect of working in an office pushing papers had lost its appeal. International travel to complete complex assignments under strict deadlines and under constant stress was no longer exciting. I wanted something completely different in life!

Hence, in 2000, we went to San Diego, where I had lived during the 1970s, to look for a suitable property to rent out before converting it into our retirement home. We found a town house that was affordable, and we found a fantastic property manager. In August 2005, we arrived to reclaim it.

We spent the first year of retirement furnishing the new house and settling in. Because the house was in walking distance of a community college, I began taking classes in travel and tourism and to update my computer skills. For a time, I considered starting a new career in the travel industry. I also took out a membership in a local fitness center and enjoyed daily walks in the neighborhood.

In the travel classes I discovered ocean cruising. Starting with a weeklong cruise to Hawaii in 2006, we have made these annual vacations. On cruises to Alaska, up and down the Pacific Coast in Mexico, through the Panama Canal, and with stops at different ports in Central and South America, we have visited friends and family and met fantastic people with whom we’ve stayed in contact over the years.

I continued searching for the ideal retirement activity. I spent a year learning the insurance industry. I completed the training course and was state-certified, but concluded that it was not right for me. What I really wanted, I discovered, was a part-time job that would get me out of the house to meet people and give my wife time for herself. That led to a five-year stint as a part-time “security guard” certified by the State of California. I received security training—never in firearms, which I detest—but worked in crowd control and ushering people who attend sports and entertainment events at large venues.

Finally, just three years ago, I found my ideal retirement job—as an associate with Home Depot. Working in the Gardening Department three to four days a week on four-hour shifts keeps me constantly walking, bending and stretching to water plants and load bags of rocks and fertilizer. I’ve shed 25 pounds, brought my pants size down two inches, and stayed fit. Also, I use my Spanish to help customers who prefer that language. And the Met Life dental insurance offered by Home Depot to its part-time employees beats what I left the federal government with 10 years ago!

Volunteer Work: Bigger Opportunities in Smaller Towns

BY MARK LORE

I’d suggest that those approaching retirement begin to develop interests not connected to the Foreign Service. For a few years after my retirement at age 59, I traded on my FS background. I taught at FSI and Shenandoah University, gave talks to adult education classes and service clubs, and wrote several articles for the FSJ and other publications. Gradually, however, these “gigs” vanished. Unless you are actively engaged on a daily basis with the issues, your usefulness to others inevitably atrophies. One should have a Plan B.

For me, the fallback has been community volunteer work. In this, I was fortunate to have settled in small-town America (Winchester, Virginia) where the competition is less but the opportunities can be surprisingly diverse. I have directed a local film society and served on city boards that oversee historic preservation and downtown revitalization. I’ve also been on a variety of nonprofit boards, as well as taking an active role in my local Unitarian Universalist congregation.

Volunteer activities can be more challenging than one might think. Successfully leading others in a no-pay environment can arguably be more complicated than dealing from a position of authority in an embassy or a departmental bureau. I’ve drawn often on some of the management tools I learned in the Foreign Service, particularly from the deputy chief of mission course. Unlike in the FS, however, the payoff is that you can build something from beginning to end and take personal ownership of it. A taste for fundraising is usually critical, as is a willingness to stay reasonably up-to-date with fast-evolving communications technology.

So unless you have the credentials and contacts to remain active in foreign affairs, identify your other pursuits early on. If these suggest further study or training, make the investment as soon as possible. It can be hard to gear up once you’re in your late 60s and 70s.

Back in Academia After an “Interlude”

BY JAMES F. CREAGAN

James Creagan discusses the work of a diplomat at the Vatican with a student in the course “The Holy See and World Affairs.”

Courtesy of James Creagan

In joining the Foreign Service, I never intended to stay “for life.” It was to be an interlude, perhaps five years, in the life of a professor. I thought that some Foreign Service experience would be useful in teaching foreign policy and international relations to future students. That five-year interlude turned into almost 35 years for me and for my family. It went by in a flash.

I had imagined myself a minor Kissinger, who could enter government and return to Harvard as a full professor unscathed by the government experience—even ready for another Department of State stint at some point. I dropped out after tours in Mexico City and San Salvador to return to where I thought the action was in the early 1970s, the campus. I tried to quit the Foreign Service, but my terrific ambassador, Bill Bowdler, convinced me to take leave without pay instead.

After a year at Texas A&M, I was ready for the world again. So off we went, Gwyn and I and the children, to successive posts in Rome, Lima, Naples, Lisbon, Brasilia, Vatican City, São Paulo, New York City, Rome and Tegucigalpa. It was a long run, with an ambassadorship and the fun and grind of running two embassies in Italy and a consulate general in Brazil. We spent only two years out of 34 in Washington, D.C. It was the old Foreign Service, and the focus was on the foreign.

Along the way, I was lucky to have had the opportunity to teach a course or to lecture at universities in several countries. After I retired, the Board of Trustees at a private university in Rome lured us back to Italy. Six-plus years as university president there meant that we had lived 18 years or so in Italy. Tough duty.

During the last 10 years I have been a professor in San Antonio and have now returned to St. Mary’s University as professor of diplomacy—where I taught 50 years ago and where I met my wife of 50 years, Gwyn. The circle of life. I am honored to hold the professorship named for an old friend and late colleague, Ambassador Eugene Scassa, a friend of many of us veteran diplomats and a great mentor to a whole cohort of this century’s Foreign Service officers.

My advice would be to not plan your entire career. Think of five years, and see what happens. There is lots of life after the Foreign Service. In the meantime, go for the experience and for the great opportunity to serve our country and, through diplomacy, improve our world.

Karate Anyone?

BY ROBERT H. CURTIS

Robert Curtis, at right in this series of photos, demonstrates techniques for responding to a certain kind of attack by grabbing the attacker’s hand and wrenching his arm or elbow to break it (1), performing a classic arm bar (2) and delivering a kick with a heel to the ribs of the attacker (3).

Courtesy of Robert Curtis

People say that happiness and satisfaction in retirement require that you have goals and interests to keep you busy. It is never too early to begin thinking about what you will do when you retire.

For me, retirement after 34 years of government service provides the opportunity to focus on gardening, reading, studying in college-level courses, teaching a course at George Mason University and teaching traditional adult-focused Okinawan self-defense karate—my lifelong passion.

I have been a student of an Okinawan Karate Grand Master, now a 10th Degree, since 1979. In spite of the challenges of a Peace Corps assignment in rural Paraguay and four overseas postings along with Washington assignments in the Foreign Service, I continued to practice and teach karate.

When I began studying the martial arts I was unconcerned with, and probably unaware of, the long-term physical benefits it provides. Older masters refer to karate as the pathway between self-defense and self-discovery, because it develops both your body and your mind. Unlike competitive sports, practicing the martial arts continues to improve your mental focus and physical movement efficiency as your skill levels continue to increase.

My 84-year-old instructor holds an annual national training seminar where most of the senior instructors, now in our 60s and 70s, gather with our students. Surprisingly, the younger and stronger competitive black belts are hard-pressed to keep up physically with us old guys. We have been doing this for decades, and our physically efficient techniques are much faster than their attacks and defenses.

When I first moved to Washington, D.C., with a master’s degree from Michigan State University, my instructor, now an internationally renowned Okinawan Karate Grand Master, told me to teach a few students wherever I went. Teaching karate to others would force me to relearn and improve my skills over and over again.

Each new assignment required starting a new school—securing adequate space and then finding interested students, too! While overseas, I regularly instructed fellow FSOs, members of the local Marine detachment and local security personnel. While in the United States I normally focused on building a more stable student base.

In 2008, I was promoted to 7th Degree, Karate Master, by the Okinawan Shidokan Shorin Ryu Karate Association.

With retirement, I changed my small “club” karate school format to a more commercial format. I had to learn how to set up a business plan, rent space, run marketing campaigns and comply with local business laws and regulations. The learning curve can be steep and painfully expensive (I can provide gory details of seemingly brilliant marketing campaigns that failed to provide even a single new student).

Are the martial arts for you? Basically, if you can walk, you can practice the martial arts. We have all seen slow graceful movements of morning Tai Chi practitioners in Chinese parks. Most of these folks seem to be of retirement age, or older, and many only started practicing in the last decade or so. One of my newer students began karate practice after nearly 40 years of government service. This individual in his mid-60s quickly adapted to our practice and became one of our regular class members, and younger students now often ask him for karate assistance as well as life guidance.

Travel with a Purpose

BY WILLIAM MCPHERSON

When I went through the retirement seminar at the end of my Foreign Service career, I learned a lot about taxes and estates and all of the other formalities of retiring. But the thing that stuck with me most is when the instructor asked us during one session to list three things that we would be doing after retirement. This got me thinking about what I was really interested in. I thought about travel, of course, and possible use of my experience in some academic setting.

What worked out best for me, however, was the following:

• Volunteer Work. In the Foreign Service, I had become interested in the use of technology in the State Department and, in fact, had a short Foreign Service Institute assignment on the use of personal computers in diplomacy. After retiring, I found volunteer work with SeniorNet, a nationwide computer instruction service for seniors. I am now working with the Seattle Mayor’s Office for Senior Citizens on their “Seniors Training Seniors” computer program.

• Part-time Conference Reporting. I am not a good tourist, but I did enjoy travel with a purpose: reporting on more than 25 environmental conferences around the world for Earth Negotiations Bulletin. This kept me current with international negotiations on the environment, particularly climate change.

• Writing. It is perhaps a cliché that we are all writers, but I did put my writing experience to work to publish three books on climate change. (They have been listed in “In Their Own Write” in The Foreign Service Journal.) I found the experience of writing to be a very satisfying activity, made much better with the availability of the Internet for research. It is also an opening wedge for entrée to the academic world, where I have been able to participate in seminars.

A Passion for Environmental and Life Design

BY DEBORAH HART

Deborah Hart attends to chickens as part of her volunteer work with Interfaith Food Shuttle in Raleigh, North Carolina. She frequently volunteers with local food security nonprofits.

Courtesy of Deborah Hart

To be honest, I have never thought about retirement as a goal. What do I wish I had known earlier about retirement? I can’t really say… maybe, how much fun it would be. So far, I don’t have any regrets about how my “retirement” has proceeded. I am surprised that I am so much busier than I have ever been in my life. My younger self might have been surprised about that, but I am not sure that knowing it would have made any difference!

The first third of my Foreign Service career was spent as a consular officer and I relished the opportunity to develop systems to improve customer service as well as effectiveness and efficiency. However, the second third was spent trying desperately to change my cone to what became my true love—public diplomacy. Fortunately, I finally was able to reach my goal and become a public diplomacy officer. I wish I had known more about the cones before I joined the Foreign Service!

Right now is a very exciting time of my life because I have been able to delve deeper into some lifelong passions that revolve around personal health and the health of the environment. Since retiring I have become certified in permaculture design and as a primal blueprint expert. I have developed a holistic approach to lifestyle design known as PermaPaleo, which employs the complementary approaches of permaculture (or restorative agriculture, if you will) and primal/paleo to help me live a life that supports my health and that of our earth.

The same social media skills that I practiced in the Foreign Service serve me well—I am still a bit of a geek and an early adopter of whatever is the newest way to communicate. My latest love is Periscope and live video using my smartphone.

My advice to the newly retired? Keep learning! Check out programs like the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. There is probably one near you. Never miss a chance to learn something new, and you will enjoy every day.

Act Two: Movie Reviewer

BY MIKE CANNING

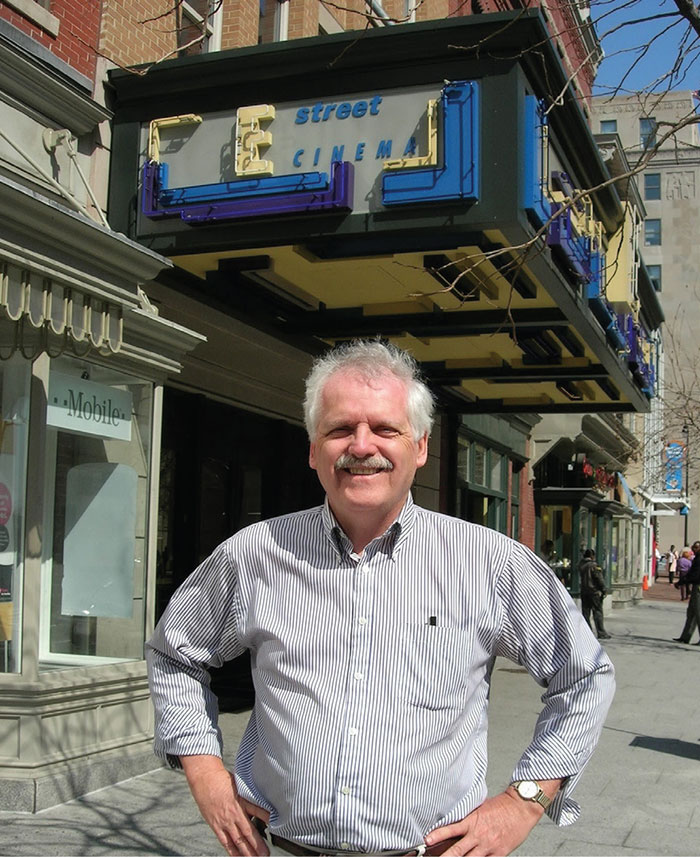

Mike Canning at Landmark E Street Cinema in downtown Washington, D.C., where he sees many of the movies he reviews.

Courtesy of Mike Canning

Whenever I tell people I review movies, they invariably exclaim: “Hey, you are so lucky; how can I get that job?” In my case, by answering an ad.

In 1993, after 28 years in the Foreign Service with the U.S. Information Agency, I was attending the State Department’s retirement course and wondering what was next. While reading a local Capitol Hill newspaper, I noticed a classified ad for a “movie reviewer.” I applied and was hired, and have been writing about motion pictures ever since, thus indulging a desire I have held since I was about four. One is hardly born a movie reviewer, of course; one starts as a movie-lover.

As one of the last pre-television kids, my youthful entertainment in Fargo, North Dakota, was the picture show. Then, at the university in my hometown, I discovered foreign-language films and was captured by their exoticism, an enthusiasm further stimulated by graduate study in Germany. After Germany, motivated in part by foreign climes that the cinema had shown me, I entered the Foreign Service with USIA. There, as a press and cultural officer, I was able to indulge my film bent, finding ways to program and write about movies of all types.

At that retirement seminar, I was relaxed about what came next. My whole life had mostly been one of blessed serendipity and acceptance—as with Charles Dickens’ Mr. Micawber—“in case anything turned up.” With a good pension and a settled domestic life, I didn’t feel I had to work at something that paid, as did some anxious colleagues in the seminar.

When I started reviewing in 1993, I was looking forward to nailing some cinematic turkeys with blistering put downs. What I found out, however, was that the hard knock might be fun, but it was also facile and fleeting. I quickly came to focus on films that moved me or interested me, and thus might interest those for whom I was writing.

I was so lucky. I have kind editors who allow me to ruminate in my monthly column; I write about what interests me. I don’t write about the Hollywood blockbuster of the week but prefer to do riffs on the quirky independent effort or the intriguing new foreign flick. In discovering any good movie for myself, I aim to trigger interest in it for my reader.

If I were looking back on my callow self, how would I advise myself on a life after the Foreign Service? Probably this way: Embrace variety and change. My whole career was comprised of such change and I thrived on it. The passion that the Service nurtured—new environments, cross-cultural communications, and crafting analytical critiques—led me, in a way, to my second act, my film life. And it’s been a great gig, just like the first one.

The Joy of Flight

BY BRIAN CARLSON

Pilot Brian Carlson volunteers with Pilots ‘N Paws, a national organization through which pilots volunteer their time and airplanes to fly dogs and other animals from euthanasia shelters (mostly in the southern states) to new homes with adopting families (mainly in the northeast).

Courtesy of Brian Carlson

In the 1970s’ Embassy Caracas, a generous ambassador allowed embassy families to ride on the mission’s airplane when it went to nearby countries. The fare was free, but the destination and timing were unpredictable. Our first trip in the DC-3 to Bogota and Quito included a weather diversion to Guayaquil.

It was the beginning of a Foreign Service career enlivened with aviation. In addition to the Pan Am flights to and from posts in South America and Europe, there were small airliners to places like Canaima’s dirt landing strip. (The pilot turned circles over Angel Falls so everyone could see it!) During the Cold War days, I felt liberated every time a sparkling, modern Austrian Airlines DC-9 lifted off from a dingy Warsaw Pact airport. In the early 1990s, I felt a little shiver of trepidation when boarding doubtful-looking Aeroflot TU-134s in the Central Asian states of the former Soviet Union.

But the best were flights in small aircraft, close to the ground. For a Cold War parliamentarians’ tour, a U.S. Army helicopter flew 500 feet above the ground, doors open, up the fortified border between West and East Germany. In Norway I experienced float plane flying—taking off and landing on breathtakingly beautiful lakes and fjords—which cost less than using an airport. In Latvia, in a Soviet-design MI-8 helicopter, the Minister of Defense marveled that a few years before it would have been unthinkable to take the American ambassador across a countryside then dotted with Soviet military installations.

When I retired, I learned to fly. Piloting challenged me to use long-neglected skills. Acronyms, numbers and rules must be memorized to pass Federal Aviation Administration tests. The Foreign Service never required much math, but even simple calculations of wind and compass deviation certainly do. I learned to use hand-eye coordination in new ways, not to mention steering with my feet. Navigation by “dead reckoning” is as treacherous as it sounds.

It was a thrill not only to pass intermediate checkrides, but to fly solo and, eventually, to receive a private pilot, single engine, land certificate (PP-SEL) from an exacting examiner. An eightman partnership in a 1967 Beechcraft plane made flying affordable. Then I got my instrument rating, which means I can fly not just in daylight visibility, but also in clouds and darkness with air traffic control’s help—just like the big jets. (Well, not as fast, not as high, etc.)

A few years ago I partnered in a Cirrus SR-22—a newer, faster and more comfortable airplane. Then I got my FAA commercial pilot certificate (meaning I could, in theory, get paid to fly), as well as complex and technically advanced aircraft endorsements. Recently I qualified in tailwheel airplanes and, with a friend, bought a Super Decathlon aerobatic airplane. We lease it out to people who want to fly loops and rolls, or just fly low and slow with the doors off in summer.

Why fly in retirement? Of course, it enables fun travel. I can lecture and attend conferences. I love the ever-changing view of America from four or eight thousand feet. And aerobatics are more fun than a roller coaster!

But best is the community of flying enthusiasts. These people don’t know what an FSO is, and their backgrounds are vastly different from ours. But they all enjoy the challenges of being pilot-in-command (PIC), planning adventures and introducing newcomers to the joy of flight.

As we like to say, “If you build 5,000 feet of highway, you can go about a mile. If you build 5,000 feet of runway, you can go anywhere.”

The East Timor Guy: Area Expertise Paves the Way

BY W. GARY GRAY

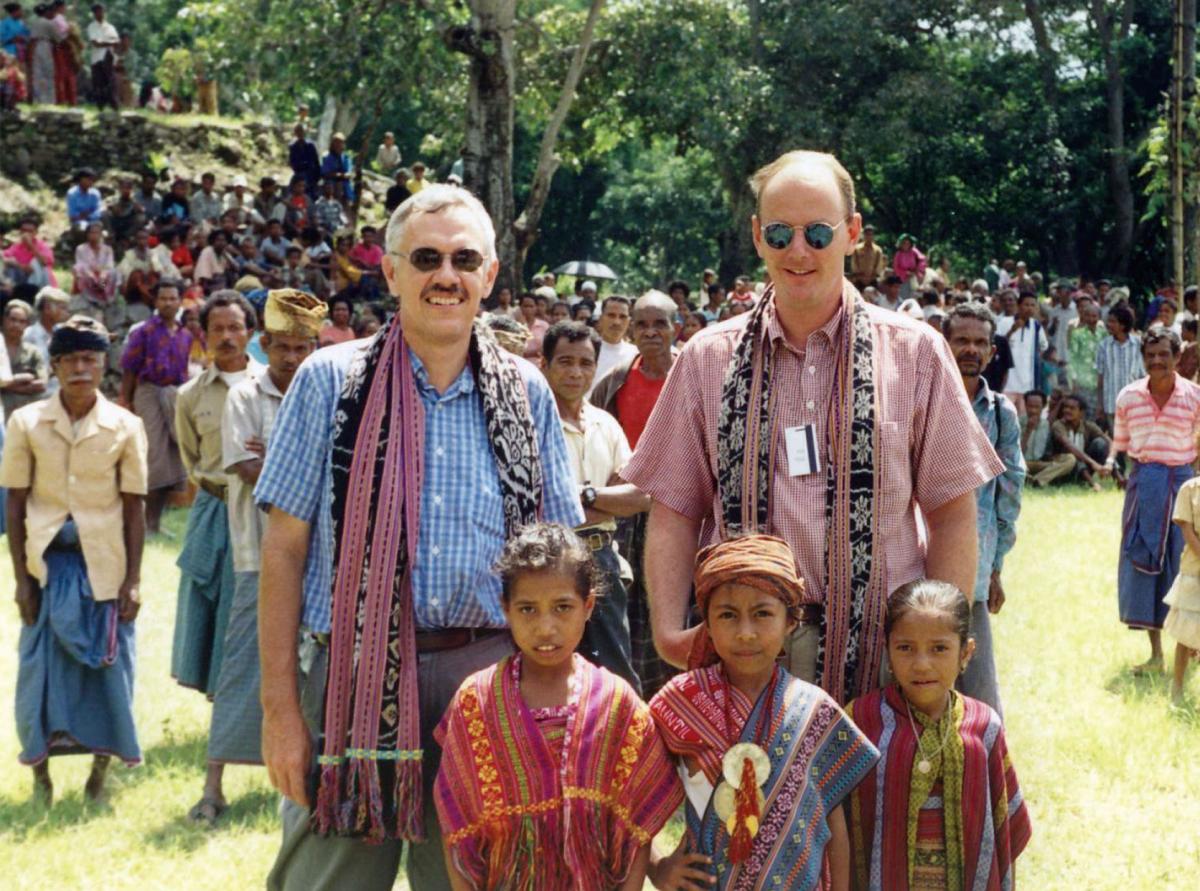

Gary Gray, at left, during a visit to Marobo village in East Timor with a representative of New Zealand.

Courtesy of Gary Gray

I retired from the Foreign Service in 2002 at age 51, long before I needed to, having another 10 years or so before any time in-class (TIC) issues would arise. At the time, I was bored in my pleasant but relatively routine job in Kuala Lumpur, having been spoiled by a series of remarkably fortuitous right-place-at-the-right-time assignments where dramatic political transitions were taking place (Pretoria, Moscow, Maputo, Jakarta, Dili).

As the first chief of the U.S. office in East Timor (2000-2001), I had perhaps peaked too soon as a de facto chief of mission and calculated that at my grade level it would be many years, if ever, before I could get back to that level. Most critically, East Timor maintained a special hold over me, and I was offered an opportunity to go back in a challenging position as chief of political affairs at the United Nations peacekeeping mission.

I nevertheless agonized for a couple of months over the decision. Australian and Canadian colleagues were able to take extended leaves of absence (up to 10 years in some cases!) to make similar moves, but State’s system offered no such flexibility: I had to make an all-or-nothing choice. Seeking advice from all quarters, I found some of my FSO friends envious, while a few others (including, most relevantly, my wife) expressed serious concern about me giving up a secure career with such good benefits.

As it turned out, I was fortunate that my first peacekeeping job continued for three years into 2005. Then I traveled to various U.N. peacekeeping missions with a new nongovernmental organization attempting to encourage the use of local procurement to boost post-conflict economies. I ended up back in Dili from 2006 to 2007 as a When Actually Employed chargé at the embassy after the new country again descended into conflict.

Following 2008 and 2009 WAE stints back in Kuala Lumpur (now more interesting with the opposition threatening to unseat the long-ensconced government), I returned to Dili in senior management positions with the new U.N. mission through 2012. I finished my more than six-year U.N. career in South Sudan in 2013, having reached the organization’s mandatory retirement age of 62, and returned to Dili in a contract position as an adviser with the embassy from 2013 to 2014.

Had I known in 2002 what I know now about how precarious, unpredictable and difficult the employment situation outside the Foreign Service can be, I may not have taken the leap. U.N. peacekeeping jobs are not tenured positions, but six-month or one-year renewable (or not) contracts. All of the jobs I actually ended up taking were the result of close contacts approaching me. During 2007 and 2008 I was more proactive, scanning listservs for international jobs, hooking up with Beltway bandit contracting firms and applying for U.N. positions, but little came of that. I did turn down opportunities to work in Iraq and Afghanistan, and other seemingly solid offers fell through at the last minute.

Watching friends and former colleagues advance to the senior ranks, I still sometimes wonder how my career would have developed had I remained in the Foreign Service; but I have no regrets. My subsequent jobs have all been challenging and rewarding. And being able to exert more control over where I wanted to be and for how long has provided better work-life balance with more opportunities for travel, attention to family issues and serious work on my tennis game. In any case, continuing to maintain contacts with FSO and FSN friends over these years provided the opportunity to come back into the State Department at some key junctures and maintain the comforting feeling that I never really left.

A Logical Next Step: Defense Department Contracting

BY MARY ANN SINGLAUB

Mary Ann Singlaub at a Society for International Affairs holiday party at Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum in Washington, D.C., in 2015. SIA is the premier U.S. association for training in export and import licensing, one of the skills Singlaub developed as a defense contractor after leaving the Foreign Service in 1999.

Courtesy of Mary Ann Singlaub

I entered the Foreign Service shortly after graduate school (an M.S. from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service) and did not give much thought to life after the Foreign Service, much less retirement. For me, Foreign Service was a desirable career path to follow after growing up as an Army brat, but not one I had planned much ahead of time.

On reflection, perhaps the most useful advice I could give my younger self about serving in the Foreign Service and planning for life beyond, is this: networking is the key. I constantly underestimated this as I breezed through my Foreign Service assignments, leaving both good friends and excellent contacts, but also questionable Foreign Service supporters, in my wake.

Never being one to bow to authority for the sake of it, I questioned my superiors’ decisions and almost always expressed my opinion. This is not helpful etiquette for an FSO in terms of promotions and assignments. Add to that some health issues and a Level 2 Medical Clearance, and I was suddenly no longer “worldwide available.” Despite entering the Foreign Service with fluent German and Italian, without that string of senior officers willing to recommend me without reservation, it was often a struggle during bidding time.

When I was selected out in 1999 as a tenured FS-3 (how embarrassing!), I did not bother to go to the Foreign Service Grievance Board. They would not allow me to “grieve” from my fabulous posting in Bern, so my thought at the time was just to get out and see what other jobs I could find. Luckily, I was able to take advantage of my political-military experience and Top Secret security clearance to embark on a second career as a Department of Defense contractor.

Between contracts providing international security and policy support to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization, and the Navy and Army, I used the networking skills I had developed all my life to find my next contract. Networking is crucial in the Foreign Service and also in the defense contracting arena.

I would encourage anyone in the Foreign Service to continue to develop outside interests and contacts both overseas and stateside. One never knows when that seven-year window might creep up, or one of those “Areas for Improvement” required on every employee evaluation report will haunt you in the next promotion review or assignment cycle.

My political officer background is always a topic of interest in job interviews, and has served me well in my new obsession with Toastmasters International, the worldwide public speaking and leadership organization. Serving as resident of a Toastmasters Club in McLean, Virginia, teaching English for Speakers of Other Languages and remaining active in networking associations in the international field are all part of a logical progression from my Foreign Service background.

There is life after the Foreign Service, and it goes far beyond that part-time gig as While Actually Employed (WAE) that so many retired FSOs rely on. Step away from the department, and you will discover excellent opportunities to utilize those diplomatic and networking skills you displayed in the Foreign Service!

You Need a Vocational Focus

BY ANN GAYLIA O’BARR

What do I wish I had known earlier about retirement? How few Americans are interested in foreign affairs or what goes on in other countries or the fact that the United States is not the center of the universe to everyone on the planet.

What advice would I give my younger self about planning for life after the Foreign Service? Take a few months to decompress, read, think and enjoy activities you haven’t had time for before. But avoid getting stuck in this mode. Plan to enter another career, not necessarily full time or involving a lot of stress, but you need a vocational purpose after leaving FS life.

What do I wish I’d known before joining the Foreign Service? How important language is to the job of an FSO. I wish I’d learned more languages and taken more courses in college before I was under the stress of language training and examinations.

As for my post-Foreign Service life, writing remains my first love. I wanted to be a foreign affairs correspondent, combining my desire to experience foreign cultures with writing. I’ve done what I wanted in two steps: first living in foreign cultures and now writing articles and novels, marrying the experiences with literary undertakings.

A Full Second Career: International Corporate Executive

BY JOEL BILLER

When I retired in 1979, there still were relatively few opportunities in the private sector to work internationally. I was lucky enough to find one.

After a first tour as a consular officer, I spent my entire career in the economic cone. At one time or another I worked on international finance, trade, economic development, transportation and labor. I spent nine years working on European affairs, mostly having to do with what was then the European Economic Community, and then six years in Ecuador, Argentina and Chile as economic counselor, with a second hat as assistant director or director of the local U.S. Agency for International Development mission.

My last assignment was in the department as a deputy assistant secretary in what was then the Bureau of Economics. During those days the State Department managed the commercial attaché network, and that was one of my responsibilities. It was not a happy job because the Department of Commerce chafed about not having an independent foreign commercial service. But it had a happy result for me. During the five years of that tour, which turned out to be my last, I came into contact with a large number of companies engaged in international business. When I retired, I found that I had a very useful contact list.

One of the companies on that list was Manpower Inc., a Fortune 500 corporation in the personnel staffing and management business. About 80 percent of its business was in Western Europe and Latin America, and it was headquartered in Milwaukee, where my wife and I had grown up and still had family. It was a perfect match. I spent the next 30 years as an international corporate executive.

I drew heavily on my Foreign Service experience. I had to learn the language of corporate financial statements, shareholder relations and a little bit about marketing, but after that it was analysis, negotiation and representation. Most of my time was spent negotiating acquisitions and joint ventures and opening new markets.

Some of my time was spent doing almost exactly what I had done in my last few years in the Foreign Service. When I was in EB I had participated in U.S. delegations to United Nations specialized agencies like the International Civil Aviation Organization, World Intellectual Property Organization and International Maritime Organization. With Manpower I found myself a U.S. representative on the employer delegation to annual meetings of the International Labor Organization. For the five years before I finally retired I was president of an international industry trade group headquartered in Brussels.

I have never regretted the time that I spent as a Foreign Service officer. I relish the memory of those years: the friends, the places, the experiences. I love living abroad, and I was fascinated by life in Washington. But I never regretted leaving when I did, still young enough to have a full second career.

From Diplomat to Solar Cooking Fanatic

BY PATRICIA MCARDLE

Sudanese women in the Iridimi refugee camp in eastern Chad have been constructing simple solar cookers like the one shown here for distribution to refugee families for years.

Courtesy of Patricia McArdle

During entry-level officer training, new diplomats are often asked to ponder the challenge we all face at some point during our careers—what to do when you disagree with a policy you are required to defend. Retirement frees us from that conundrum and allows us to speak truth to power without risking our jobs or our pensions.

My primary activity since returning from a 2005 tour of duty in northern Afghanistan and retiring nine months later has been the promotion of a renewable energy technology—solar thermal cooking. Over the past decade I’ve demonstrated solar cookers in Sudanese refugee camps, on the Navajo reservation, in Nepali villages, central Mexico, Morocco, India, Guyana and all over Washington, D.C. In 2007 I organized the first in a series of annual solar cooking demonstrations in the center courtyard of the Pentagon.

How did this retired grandmother become a solar cooking fanatic? Afghanistan’s abundant sunshine, its vanishing forests and the sad processions of small children I saw everywhere hauling mounds of brush back to their villages for their mother’s cooking fires reminded me of a solar cooker I’d made as a Girl Scout. This memory inspired me to build a new one and demonstrate it when I accompanied NATO military observation teams on peacekeeping patrols in northern Afghanistan.

The first time I boiled a pot of water with a cardboard and foil solar cooker for a group of astounded Afghan villagers, I was hooked. I assumed that USAID and State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration would share my enthusiasm when I came home. They did not. Ten years later, the U.S. government continues to spend millions of dollars improving and promoting biomass-burning stoves and even liquefied natural gas stoves but still almost nothing on solar cookers, the cleanest of all cook stoves.

One of my initial “political” acts after retiring was to join the first 1,000 volunteers selected for Al Gore’s Climate Project training. After attending sessions in Nashville, we fanned out across the country to give presentations based on his film, “An Inconvenient Truth.”

My personal politics included more than a concern about global warming. On Sept. 11, 2001, I was looking out a window at FSI and saw a black mushroom cloud billowing into the cloudless blue sky after American Airlines Flight 77 hit the Pentagon. While I supported our initial military actions in Afghanistan, I was horrified at the unprovoked invasion of Iraq in 2003. I knew that when I returned from Afghanistan I could not in good conscience accept another overseas assignment, since I would be required to defend this disastrous war of choice. I chose to leave the service early, albeit quietly.

My other passion is writing—and I don’t mean briefing memos and talking points. When I returned from Afghanistan with hundreds of pages of journal notes and a minor case of PTSD (which like many of my colleagues I did not discuss with anyone), I decided to turn my notes into a novel—a literary catharsis of sorts. I entered my manuscript in the 2010 Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award contest and miraculously won a publishing contract with Penguin Books later that year.

I have another novel in the works, and I continue to produce short videos on solar cooking and related topics for my “solarwindmama” YouTube channel.