Calling It Like We See It

President's Views

BY BARBARA STEPHENSON

This month’s Journal covers the AFSA annual awards ceremony and spotlights the 2016 award winners. This makes for inspiring reading, as we explore what our colleagues are doing to achieve our collective mission. One friend now serving at the Foreign Service Institute tells me she scours the AFSA awards write-ups for case studies to highlight best practices in her training classes.

Foreign Service Core Precepts

Excerpt from the Core Precepts

Decision Criteria for Tenure and Promotion in the Foreign Service Leadership Skills/Openness to Dissent and Differing Views

Entry-Level: Exhibits moral courage and intellectual integrity. Publicly supports official decisions while using appropriate dissent channels in case of disagreement. Resolves disputes using appropriate mechanisms.

Mid-Level: Encourages frank communication with colleagues and subordinates. Discerns when well-founded constructive dissent is justified; advocates policy alternatives and guides staff to do the same. Recognizes employee dissent through awards programs.

Senior-Level: Encourages and expects personnel to express opinions and to use dissent channels; accords importance to well-founded constructive dissent and solicits, weighs, and defends its appropriate expression. Recognizes and supports moral courage.

The annual awards ceremony is a great AFSA tradition, one that recognizes excellence and courage. The AFSA awards program makes our profession stronger.

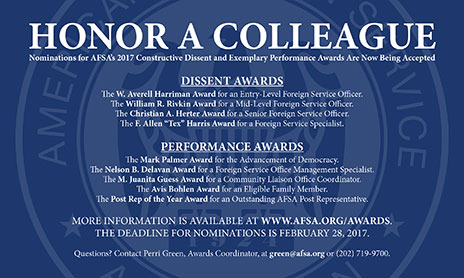

AFSA gives a variety of awards—one for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy, several outstanding performance awards and, unique in the U.S. government, four awards for constructive dissent—at the entry level, mid-level, senior level and by a specialist.

This year, after the kind of spirited, principled debate that represents AFSA at its best, only one award for dissent was granted. Governing Board and Awards Committee members agreed on the need for better, clearer guidance on what constitutes dissent in the Foreign Service—beginning with how to distinguish between dissent and the equally important, but distinct, act of taking initiative and finding innovative ways to approach challenges.

We resolved to produce a more robust definition of dissent in time for next year’s nomination process. This column is meant to contribute to that thought process and invite your input.

We in the Foreign Service deploy worldwide—to protect and serve, yes, but also to understand the local context and call it like we see it. Sometimes Washington wants us to deliver something we know is not achievable in that context. Sometimes we know that even trying would cause a backlash and impede achievement of other goals.

It is our obligation to point that out, to offer our best judgment and, when possible, alternatives (see “Foreign Service Core Precepts,” below). This is the basis for constructive dissent as we have traditionally defined it. The State Department’s Dissent Channel is one way—the institutional vehicle—to deliver that dissent (see “The Dissent Channel,” below).

The same obligations to speak up apply for matters related to the management of our own institution, not just for classic foreign policy issues. We must all think of ourselves as stewards of the Foreign Service and act accordingly, working to establish and maintain well-functioning embassy platforms and healthy career paths for the next generation. Because the Dissent Channel is restricted to “substantive policy” issues, dissent on management matters must be conducted through other channels.

The Foreign Service adds tremendous value every time we advise with precision about what will work, and what won’t work, in the local context at our posts.

The AFSA awards program recognizes constructive dissent on management issues as well as foreign policy issues. This year’s Rivkin Award winner is a great example of the former.

The Dissent Channel

Excerpt from 2 FAM 070 Dissent Channel

2 FAM 071 POLICY

2 FAM 071.1 Policy Statement

a. It is Department of State policy that all U.S. citizen employees, foreign and domestic, be able to express dissenting or alternative views on substantive issues of policy, in a manner which ensures serious, high-level review and response.

b. The State Department has a strong interest in facilitating open, creative, and uncensored dialogue on substantive foreign policy issues within the professional foreign affairs community, and a responsibility to foster an atmosphere supportive of such dialogue, including the opportunity to offer alternative or dissenting opinions without fear of penalty. The Dissent Channel was created to allow its users the opportunity to bring dissenting or alternative views on substantive foreign policy issues, when such views cannot be communicated in a full and timely manner through regular operating channels or procedures, to the attention of the Secretary of State and other senior State Department officials in a manner which protects the author from any penalty, reprisal, or recrimination.

c. Freedom from reprisal for Dissent Channel users is strictly enforced; officers or employees found to have engaged in retaliation or reprisal against Dissent Channel users, or to have divulged to unauthorized personnel the source or contents of Dissent Channel messages, will be subject to disciplinary action. Dissent Channel messages, including the identity of the authors, are a most sensitive element in the internal deliberative process and are to be protected accordingly.

2 FAM 071.2 Scope

The Dissent Channel is reserved for consideration of dissenting or alternative views on substantive foreign policy matters. The Dissent Channel may not be used to address non-policy issues (e.g., management or personnel issues that are not significantly related to substantive matters of policy). Complaints relating to violation of law, rules, or regulations; mismanagement; or fraud, waste, or abuse may be addressed to OIG/INV. Classification challenges should not be addressed through the Dissent Channel.

Lest we come across as simply nay-sayers (as we might to interagency partners whose leadership principles do not embrace dissent as fully as ours), let me note that we routinely add as much value pointing out what will work as we do pointing out what won’t work.

We who typically understand the local context better than anyone else in the U.S. government are often the first to see that a long-shot goal might just be achievable if we frame the arguments a certain way, avoid that third rail, garner support from this key group while not alerting another too early.

Delivering on those long-shot goals may show incredible, even unusual, initiative and innovation. It may be outstanding performance, but it’s not dissent.

The Foreign Service adds tremendous value every time we advise with precision about what will work and what won’t work in the local context at our posts. This is a core role of the Foreign Service, and it is often the basis for well-founded constructive dissent.

There is something else to consider. When AFSA gives only one award for dissent, a question naturally arises: Is the space for constructive dissent closing? This is both a fair question and a powerful, foundational one, given our role in the interagency “ecosystem.”

Pointing out that something Washington wants just won’t fly requires courage and often risks repercussions. The perceived price for doing the right thing, for engaging in constructive dissent, rises, I am convinced, when we feel insecure in our careers.

When, for example, mid-level officers need to worry about there being more bidders than jobs, or when senior officers see their career paths blocked by appointees from outside the Foreign Service, we shouldn’t be surprised if dissent declines.

Our dissent awards honor those who stand up and call it like they see it. We all need to defend the space for constructive dissent, which is, in my view, inextricably intertwined with defending a strong, professional career Foreign Service.