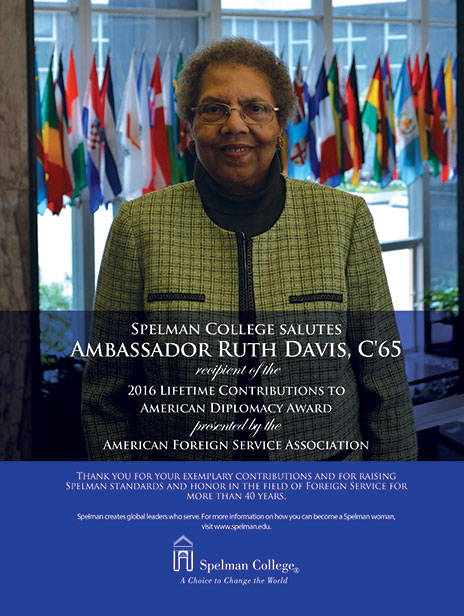

A Foreign Service Trailblazer—Ambassador Ruth A. Davis

The recipient of AFSA’s 2016 Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award talks about her Foreign Service career and her pioneering work to advance diversity and promote professional excellence at the State Department.

AN INTERVIEW WITH AMBASSADOR RUTH A. DAVIS

AFSA / Joaquin Sosa

AFSA / Joaquin Sosa

Ambassador Ruth A. Davis received the American Foreign Service Association’s Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award in recognition of her distinguished Foreign Service career and lifelong devotion to diplomacy at a June 23 ceremony in the State Department’s Benjamin Franklin Room (for her speech and coverage of the ceremony, see AFSA News; click here to watch her acceptance speech).

Born in 1943, Amb. Davis received a bachelor’s degree from Spelman College and a master’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Social Work in 1968. She joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1969.

A trailblazer throughout her 40-year career, Amb. Davis was the first female senior watch officer (SWO) in the Operations Center (1982-1984), the first African-American director of the Foreign Service Institute (1997-2001) and the first African-American female Director General of the Foreign Service (2001-2003). She was also the first and only African-American woman to be named Career Ambassador, the longest-serving officer at that level and, upon retirement, the highest-ranking Foreign Service officer. She is also the first African American to be awarded AFSA’s Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award.

Amb. Davis’ early overseas postings were as a consular officer in Kinshasa, Nairobi, Tokyo and Naples. She went on to hold many senior positions besides those in which she was the “first.” She served as consul general in Barcelona (1987-1991), ambassador to Benin (1992-1995), principal deputy assistant secretary for consular affairs (1995-1997), distinguished adviser to the Ralph Bunche International Affairs Center at Howard University (2003-2005) and senior adviser in the Bureau of African Affairs (2005-2009). Amb. Davis retired from the Foreign Service in 2009.

She is the recipient of numerous awards, including the State Department’s Superior Honor Award (1999), and its Arnold L. Raphel Memorial Award for mentoring other, especially junior, officers (1999). She also received two Presidential Distinguished Service Awards (1999 and 2002), the Secretary of State’s Distinguished Award (2003), the State Department’s Equal Employment Opportunity Award (2005), the Director General’s Foreign Service Cup and honorary doctorates from Middlebury and Spelman Colleges.

A lover of opera, Amb. Davis has remained engaged and active in retirement. She holds leadership positions in and works with a variety of organizations to promote women’s economic empowerment, recruitment and retention of minority members of the Foreign Service, and the expansion of career-long training in the Foreign Service.

Foreign Service Journal Editor Shawn Dorman interviewed Amb. Davis on June 9.

Foreign Service Journal: Congratulations! I can’t think of a more deserving person for the Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award.

Ruth A. Davis: Thank you.

FSJ: You grew up in the South during the last years of legal segregation. What impact did this have on you and your decision to go into public service?

RAD: Growing up in the South at that time was the determining factor in my interest in public service. As a proud child of the South, I bear the scars of segregation and discrimination, but these scars ignited in me a passionate desire to make the world a better place.

You know the legend of the phoenix—the bird that rose from its own ashes and was more beautiful and magnificent than ever. Well, I was born in Phoenix, Arizona, and raised in Atlanta, whose symbol is that bird. Consequently, I always believed that from ashes you could make beautiful things, from chaos you could make peace, and from despair you could bring happiness—but only with hard work, dedication and determination. I knew I wanted to make a difference, and knew that I had to find my niche.

FSJ: What brought you to a career in diplomacy?

RAD: When I was a junior at Spelman College, I was awarded the Charles E. Merrill Scholarship, which gave me the opportunity to study and travel abroad for 15 months. I chose to study in Dijon, France, and while there, I met a number of African students who were preparing to return to their respective, recently independent countries to assume active roles in dealing with the political, economic and social problems of post-colonial Africa. I found it an exciting prospect and wanted to be on the ground in Africa as the nation-building process began and as the U.S. government worked to partner with and help support the development of these newly independent countries. What better way to do this than as a U.S. diplomat?

It was like being in the United States with Mr. Washington and Mr. Jefferson, when they were building our country.

FSJ: You joined the Foreign Service after getting a B.A. from Spelman College and an M.A. from the U.C., Berkeley School of Social Work. Did you see a connection then, and do you see one now, between social work and diplomacy?

RAD: Yes, there is a strong connection between social work and diplomacy. Social work is about helping and protecting people; it promotes change, development and the empowerment of people to address life’s challenges—it’s about social change at the individual and community level.

I entered the Foreign Service as a consular officer, and one of my mandates was the welfare and protection of American citizens abroad. That covers a lot of ground—from registering American citizens’ births to handling estate issues and many overseas life issues in between, such as ensuring that American citizens in trouble abroad receive equal treatment under local laws.

At the more senior level of the Service I served as U.S. ambassador to the Republic of Benin, where I dealt with development issues and encouraged the empowerment of civil society, especially women. Here in America, we automatically depend on efficient services provided by our local and federal government. In developing countries, the challenge is to create or improve the managerial and administrative structures necessary to provide basic public services. A background in social work gave me a leg up in helping the Beninese create the basic structures necessary to build and sustain their democracy.

FSJ: Who were your role models coming in?

RAD: My most important role models besides my parents, who taught me the value of hard work, integrity and spirituality, were my college and university professors. Dr. Lois Moreland of Spelman, a promoter of overseas experiences for students, supported my selection as a Merrill Scholar. Also, noted sociologist and author Dr. Andrew Billingsley—who I worked for as a research assistant while he was writing his acclaimed work, Black Families in White America—taught me a good deal about writing and research that served me well in the Foreign Service.

Following a meeting on revamping and strengthening State’s visa anti-fraud procedures in 1996, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs Ruth Davis meets with her mentor, Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs Mary Ryan.

Courtesy of Ruth A. Davis

FSJ: You joined the Foreign Service in 1969. What was it like taking the Foreign Service exam then? Were there other African Americans in your A-100 class? Did you feel welcome?

RAD: Yes, I entered the Service in January 1969. Much like the Pickering and Rangel Fellows, I was a Foreign Affairs Scholar—a program supported by the Ford Foundation that was designed to increase the number of minorities in the Service. I had just finished my studies at the University of California at Berkeley and found Washington and the Foreign Service to have a much more formal atmosphere.

I received a warm welcome from my fellow Georgian and future Director General of the Foreign Service, Edward “Skip” Gnehm. In fact, Skip and I drove down to Georgia on a couple of long weekends and had the occasion to do a sit-in—against my wishes, but Skip insisted that we would not leave a restaurant below the Mason-Dixon line until I was served. After a while the owners acquiesced, and we were on our merry way.

What I remember most about my A-100 class was the implied expectations. One speaker told us that only about three of our 30-odd classmates would become ambassadors. It was clear to me that my classmates believed those three would come from among the white males.

FSJ: When did you join AFSA?

RAD: I can’t be precise, but I believe it was in the latter part of my service as a mid-level officer. Early on, I was disappointed with AFSA. In 1971 Alison Palmer filed a suit against the department on account of discrimination against women in the hiring, promotion and assignment process. In 1976 she re-filed the suit as a class action suit, which was eventually decided in her favor. AFSA did not join or support this class action suit.

But as I advanced in the Service, I observed and appreciated AFSA’s efforts to protect the professional interests of its members and to press for important reforms. Now, since I am retired, I appreciate AFSA more then ever for its advocacy concerning pensions and benefits, especially those related to health.

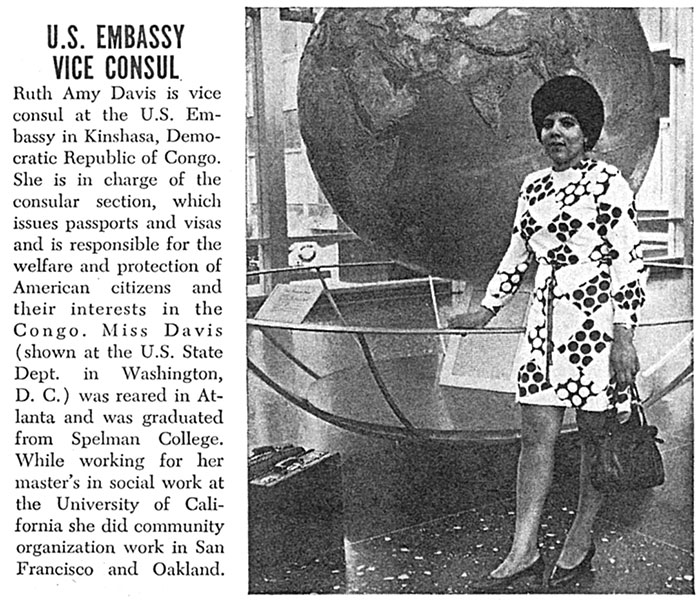

FSJ: Can you tell us how you came to be featured in Ebony magazine in 1970?

RAD: Ebony is a monthly magazine primarily for the African-American market, and at that time it had a regular column, “Speaking of People,” that featured African Americans in unusual positions as role models to encourage others to pursue similar careers. In my case, it worked. Years after the photo appeared, I was serving in Naples when I had the occasion to phone the consul in Nice, Eleanor Hicks. Eleanor informed me that she was in the Service because she had seen my photo in Ebony and had immediately declared, “I want to be like her.”

Your Career

January 1970

Ebony

FSJ: You have been a trailblazer—as an African-American woman in the Foreign Service of the 1970s, as the first African-American career ambassador and other accomplishments. What lessons can you share from these “firsts”?

RAD: I do have many “firsts” to be proud of, such as first female SWO in the Operations Center, first African-American director of the Foreign Service Institute and first African-American female Director General. I was not, however, the first African American to achieve the rank of Career Ambassador; that honor belongs to the late six-time ambassador Terence Todman. It is true, I am the first and only African-American woman to be named Career Ambassador—it’s a lonely group of only six other women: Frances Willis, Mary A. Ryan, Anne Patterson, Elizabeth Jones, Nancy Powell and Kristie A. Kenney. And, of course, I am very pleased and proud to be the first African American to be awarded AFSA’s Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award.

But to answer your question, it is not enough to be the first. That achievement must be followed by a concerted effort to ensure that I am not the last. I was very proud to be honored by the Thursday Luncheon Group in 2009 with its Pioneer Award, which symbolized my blazing a path for others to follow.

Two important lessons I learned are: First, it is incumbent on me as a leader to promote diversity. If I don’t promote diversity, probably no one else around me will, and the status quo, which does not generally include a representative number of women and minorities, will remain acceptable. Second, although I have always been cognizant of my racial identity as a determining factor in who I am, it is more important for me to be defined by my professional accomplishments and my service to humanity, especially to young Foreign and Civil Service personnel in or aspiring to be a part of the foreign affairs community.

On May 23, Ambassador Ruth Davis re-enacted the photo that appeared in the January 1970 edition of Ebony magazine, shortly after she joined the Foreign Service. Says Davis: “I am always drawn to the statue of Atlas because I believe that it is a great symbol of the importance of diplomacy in holding the world together in peace, prosperity and hope.”

AFSA / Allan Saunders

FSJ: What posting stands out the most in your memory, and why?

RAD: Cotonou, Benin—where I had the privilege of serving as chief of mission—stands out most. It was a heady time in Benin; the country was struggling to move from a disastrous Marxist-Leninist state to a fledgling democracy in 1991 when it held elections. Subsequently, our mission was instrumental in helping to build the basic structures required to support Benin’s developing democracy.

My very able USAID director, Thomas Cornell, and I chose helping to restore the devastated Beninese education system as our principal aid project, with the caveat that Beninese girls, who were previously excluded, should be included in the education equation. This, of course, had a profound impact on the lives and prospects of girls and an impact on the social fabric of the country. Among many other important undertakings, we assisted in the creation of Benin’s Constitutional Court and the country’s equivalent of our Federal Communications Commission, in addition to supporting Benin’s restructuring to a free and open market economy.

What an exciting, extraordinary time it was for me! It was like being in the United States with Mr. Washington and Mr. Jefferson, when they were building our country and defining American values. Where else, except the Foreign Service, could I have had an impact on the evolution of democracy in a developing country?

And if that’s not enough, serving in Benin put me in touch with my ancestry. In West Africa, I visited ports from which millions of slaves were shipped to the Americas. In Ouidah, Benin, I visited the Tree of Forgetfulness, around which slaves were forced to march in a symbolic severing of ties between themselves, family and Africa. I marched around the tree, but I did it backwards because I never want to forget.

FSJ: What was your favorite posting and why?

RAD: I loved all my postings, but Barcelona deserves a special mention for several reasons. First, I am proud to say, I left the post in a far better condition than I found it. Shortly after arriving, I began a search for better accommodations and stepped up the effort after my consulate was bombed by a group called the Red Army for the Liberation of Catalonia. Fortunately, although the bomb wreaked havoc, no one was killed. It was difficult to find property that met the department’s security and financial specifications. Nonetheless, I was able to locate and purchase what is undoubtedly one of the most impressive consulate building and grounds in Europe.

Second, I faced a significant challenge being the first African-American U.S. consul general. I am told that my assignment prompted some Catalans to ask, “What have we done? Have we angered the U.S. government?” In the best of circumstances, Barcelona was a very closed society, but I was determined to gain entry and respect—and I did just that. When I departed three years later, the Catalans hosted a farewell dinner for about 300 guests for me at the king’s palace, got a taped message from President Ronald Reagan complimenting my work and brought my parents over to attend the festivities as a surprise.

Lastly, I remain in touch with Catalan friends and contacts. I still work with the Barcelona Chamber of Commerce on women’s empowerment issues and joined with them and the Manhattan and New Delhi Chambers of Commerce as a founding member of the International Women’s Entrepreneurial Challenge, an organization I chair that is designed to create a global network of successful international businesswomen.

FSJ: What was your least favorite posting and why?

RAD: On account of language difficulties, Tokyo was my most challenging post. I did not occupy one of the few language-designated positions in the embassy and, consequently, arrived without language training. I had to rely on our locally employed (LE) staff to translate in visa interviews and other business that required local contacts, which was frustrating. Later, as director of the Office of Training and Liaison, as director of FSI and as DG, I pressed for more language-designated positions and more and improved language training.

FSJ: What life lessons did you learn as a consular officer? What did you like most and least about consular work?

RAD: The nature and volume of consular work gave me the opportunity, from the beginning of my career, to manage resources and people, especially LE staff. So early on I learned to manage a diverse workforce, while developing an appreciation for the work of our LE staff. In fact, it is consular work that piqued my ongoing interest in leadership and management. Working daily with the public, both foreigners and American citizens, gave me the opportunity to hone my customer service skills; and starting out in African countries where there were significant numbers of American missionaries, I also learned the relevance of religion to U.S. diplomacy and development objectives.

Having studied social welfare, I was especially attracted to American Citizen Services. I was most frustrated by working with officers who refused to see the value in serving in a consular tour. I believe consular work offers a unique learning experience, but that it is problematic to assign non-consular-coned officers to a second consular tour—as has been the case for far too many FSOs who want to get experience in their chosen career track as soon as possible. This is why I am a proponent of the Consular Fellows Program, which should be expanded to free up personnel to pursue their assigned cones.

FSJ: You were very involved in planning for U.S. participation in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics and in helping Atlanta win the bid to host the 1996 Olympics. Do you have any lessons on “Olympics diplomacy” to share?

RAD: While serving as CG in Barcelona, I was the consular corps’ liaison to the Barcelona Olympic Organizing Committee. That positioned me to not only work on the 1992 Olympic concerns of the countries represented in Barcelona, but to be an informal liaison for the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games, which was bidding on the 1996 games. It was a special privilege to travel to Tokyo with the ACOG for the announcement awarding my hometown the 1996 games, knowing that I had an active role in making the bid process successful.

Working with the 1992 and 1996 Olympics, the latter as principal deputy assistant secretary for consular affairs, gave me a fine appreciation of the value of sports diplomacy in strengthening relations between the United States and other nations, and of the important role the United States plays in making the Olympic Games successful—the Bureau of Consular Affairs for its information sharing and protection of American citizens, the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs and, most significantly, the Bureau of Diplomatic Security that works with host-country counterparts to help ensure safe and secure games.

FSJ: During your tenure as director of the Foreign Service Institute from 1997 to 2001, you focused on moving the institutional culture from being training-averse to training-committed. Would you say that shift has occurred?

RAD: The State Department has come a long way on the training front since the establishment of the School of Leadership and Management. I will never forget how astonished Secretary of State Colin Powell was when he learned of the negligible amount of time that Foreign and Civil Service personnel in the department spent on training compared to their military colleagues. The value that Powell placed on training was key to instituting basic, intermediate and advanced mandatory leadership and management training.

Consequently, now multiple generations of both Foreign and Civil Service personnel have received leadership training, and others expect to be properly trained and given the tradecraft skills they need to be successful in new jobs. So I would say that there has been a cultural shift in the expectations of the department’s workforce and in the value accorded training. However, the personnel gaps incurred, especially during lengthy language training, frequently cause pushback from supervisors and receiving posts.

FSJ: FSI’s School of Leadership and Management, which you established in 1999, is a significant legacy. What has that school accomplished and what remains to be done?

RAD: While the School of Leadership and Management has brought about a cultural shift in the expectations of the department’s workforce and in the value accorded leadership training among department personnel, challenges remain—namely, to rebuild a personnel float to assist with vacancies caused by training-related absences, and to have supervisors give the same priority to leadership skills as is given to analytical, operational and programmatic skills.

It is not enough to be the first. That achievement must be followed by a concerted effort to ensure that I am not the last.

Being Director General

FSJ: You closed your first State magazine column as DG (September 2001, “Seizing the Moment”) with this very optimistic line: “While I don’t expect to see you doing handsprings of joy in our long hallways, I hope I will soon see a bounce in your step and a gleam of excitement in your eyes, because it’s such a great time to be serving the people of the United States of America.” The Diplomatic Readiness Initiative was extremely successful, increasing FS ranks by more than 40 percent after years of shortages. What was it like being Director General at that time, essentially in charge of the biggest hiring surge in decades?

RAD: It was a very exciting time. The era of resource deprivation was replaced by a new set of challenges related to hiring, training and assigning the new recruits. We completely re-engineered the FSO hiring process, reducing the time to hire from more than two years to less than one. It required intense coordination with Diplomatic Security and MED to speed up clearances, with FSI to provide orientation and training, and with the offices of Career Development and Assignments and Resource Management to ensure that adequate assignments and positions were available for the people we hired. We finally had sufficient personnel to create a training float, and from a human resource standpoint the picture was very positive.

FSJ: Right after you became Director General, the events of 9/11 occurred. Can you describe what significant changes resulted in the aftermath of the attack, and the impact the “war on terrorism” has had on diplomacy?

RAD: With the war on terrorism, the world has become much more unsettled, placing more demands for professional, smart diplomacy and requiring diplomats capable of dealing with complex, tumultuous, rapidly changing circumstances.

The international challenges today are much more varied and seemingly more intense than when I joined the Foreign Service at the end of the 1960s. International terrorism, nuclear proliferation, cybersecurity, regional conflicts and public health crises are among the issues that diplomats grapple with on a daily basis. The challenge for the State Department is to recruit, train and assign the right people to carry out the changing demands of today’s diplomacy.

FSJ: What is the legacy of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan on the Foreign Service and diplomacy?

RAD: Regretfully, most of the increased hiring during the Diplomatic Readiness Initiative was absorbed by the demand for personnel in Afghanistan and Iraq. The State Department now faces increased demand to staff hardship posts and those that qualify for danger pay. State has created a wide range of measures and incentives to encourage officers to bid on these difficult assignments, with mixed results. The mere existence of this demand reinforces the need for a stronger State Department, better prepared to practice smart diplomacy.

FSJ: How would you describe your level of optimism about the state of the Foreign Service today?

RAD: There are numerous problems undermining the strength of today’s Foreign Service, but I am optimistic as long as organizations such as the American Academy of Diplomacy, which recently produced the report “American Diplomacy at Risk,” and AFSA take an active role in supporting and working to improve the quality and professionalism of the Foreign Service.

Diversity and Mentoring

FSJ: You’ve done so much to help increase diversity in the Foreign Service. What is your response to those who say that after years of effort to diversify the Foreign Service, it still has “a diversity problem”? (An example is the May 22 Nick Kralev Foreign Policy magazine article, which cites State Department figures showing that 82 percent of career diplomats are white and 60 percent are male.)

RAD: Section 101 (a) (4) of The Foreign Service Act of 1980 says that the Service should reflect the American population. Consequently, we must continue to strive to ensure that it becomes representative of the mosaic that is America. It has been my experience that unless there is clear and visible support from the highest levels of the department, very little effective action is taken to advance diversity interests.

We completely re-engineered the FSO hiring process, reducing the time to hire from more than two years to less than one.

FSJ: What strategies do you recommend for increasing diversity in the Foreign Service both in recruitment and retention and promotion?

RAD: Among the strategies I recommend are the following:

• The State Department should continue its strong support for the Pickering, Rangel and Payne Fellowships. These are a critical source of diversity and are bringing really outstanding candidates into the Service.

• In terms of recruitment, Diplomats in Residence should step up their efforts to identify minority candidates, referring them to the fellowship programs, internships, language programs such as the Boren Fellowship and other opportunities that spark interest in careers in the Foreign Service.

• Reach out more effectively to minority audiences, increasing the number of minority takers of the Foreign Service Written Examination.

• Pay attention to the assignment and retention of minorities in the Service. With the mid-level gap closing and promotions slowing down, special attention needs to be given to assignments and training. I was disappointed to learn of the negligible number of African Americans, Hispanics and other minorities assigned as deputy chiefs of mission, principal officers and office directors. If minority officers cannot aspire to positions of responsibility, they will not remain in the Service.

• I am also concerned about the paucity of minority Civil Servants in the Senior Executive Service, more of them at the GS-15 level should be groomed for SES positions in the department. The SES Career Development Program should be offered more frequently, and HR must ensure that those receiving the training are representative of the department’s diverse work force.

FSJ: You’ve been president and adviser to the Thursday Luncheon Group. How did that group get started, and can you tell us a bit about its work?

RAD: The Thursday Luncheon Group is one of the leading affinity groups in the department. It was formed in 1973, at a time when African-American participation in the foreign affairs agencies was increasing. Two senior U.S. Information Agency officers brought together colleagues to consider what could be done to encourage a significant role for African Americans in the formulation and implementation of U.S. foreign policy.

TLG has since grown to about 300 members and actively mentors, recruits and sponsors activities designed to help its members navigate the system, such as career development and EER preparation sessions. TLG joins with the Association of Black American Ambassadors to hold an annual reception welcoming the new cohorts of Pickering, Rangel and Payne Fellows and coordinates with AFSA annually to sponsor an intern in the department.

FSJ: You’ve been a champion for mentorship. How is the State Department doing in terms of encouraging mentorship and establishing official mechanisms for mentoring?

RAD: The State Department has a range of formal mentoring programs available to every employee—Foreign Service, Civil Service and LE staff—and the Rangel, Pickering and Payne programs seek mentors for their participants. While I applaud the department’s efforts, I believe that the most effective mentors are those who are developed through situational connections without a formal structure. Such mentors can be found in a variety of settings in or out of the workplace, in professional associations, such as AFSA, or in numerous other places. The major point is to identify and select a mentor who is thoughtful, articulate and able to offer useful career advice.

FSJ: You chair the selection committee for the Rangel International Affairs Fellowship. How successful has the program been in increasing diversity? How can the foreign affairs agencies retain minority talent once in the Foreign Service?

RAD: The Rangel Fellowship program was established in 2002, and it is having an impact on the Foreign Service. The program has selected 243 fellows; and, as of September 2016, there will be 170 in the Foreign Service and 60 in graduate school. While this is an admirable start, there is still quite a bit of work to do. Once these fellows are in the Service every effort must be made to retain their talents. Hence, the department must focus on career development, including training, promotion opportunities, good assignments and employee incentives.

Ambassador Ruth A. Davis discusses the empowerment of women and education of girls in Benin with First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton on July 13, 1995. While serving as ambassador to Benin, Amb. Davis accompanied Mrs. Rosine Soglo, wife of the president of Benin, to the White House meeting.

The White House

Retirement and Reflection

FSJ: Can you give us some highlights of the work you’ve done since retiring from the Foreign Service in 2009?

RAD: I don’t often share this, but I’m going to say it here, hoping that it might inspire others. Here goes: In 1999, I was diagnosed with multiple myeloma and told I had a maximum of three years to live.

However, thanks to breakthrough clinical treatments, two bone marrow transplants and continued excellent medical care here at the Washington Hospital Center and at the Myeloma Institute of the University of Arkansas, I am surviving multiple myeloma plus a number of other health issues and have been determined not to let them deter me from making a difference in this world.

I am busily involved in building a global network of successful international businesswomen as chair and founding member of the International Women’s Entrepreneurial Challenge Foundation, which will celebrate its tenth year of growth and success in 2017.

My other activities include chairing the International Mission of Mercy, USA, which provided aid for orphans following Nepal’s April 2015 devastating earthquake and, more recently, sent medical supplies to Ecuador following the April 2016 earthquake. I also chair the annual Selection Panel for the Charles B. Rangel Fellowship program, which has assisted the department’s diversity efforts since 2002.

As vice chair of the Association of Black American Ambassadors, I mentor aspiring and professional Foreign and Civil Service personnel and lobby the State Department on diversity issues. As a member of the Defense Language Institute Board of Visitors of Monterey, California, I contribute to the enhancement of language training for members of the U.S. Armed Services. And as senior adviser for the International Career Advancement Program, I provide leadership training to mid-level, underrepresented professionals in international affairs.

Finally, I serve on several boards of directors, including the Senior Seminar Alumni Association, American Academy of Diplomacy and the Washington Institute of Foreign Affairs, where I am also vice president.

FSJ: What do you see as the essential ingredients for a successful diplomat?

RAD: A successful diplomat must have a combination of strong professional and interpersonal skills. I place leadership and management at the top of the diplomatic skills pyramid. Today’s diplomat must be prepared to practice not just diplomacy, but mega-diplomacy. To do so requires a broad knowledge of the world and current issues viewed through a historical lens; vision; good negotiating, verbal and written communications skills; and adept use of information technology. On the interpersonal front it requires the ability to navigate, understand and interpret foreign cultures—language ability being extremely important. Also needed is the ability to work effectively with and inspire both American personnel and FSNs to give their best in accomplishing U.S. goals and objectives. Successful diplomats must have integrity, courage and self-confidence, preferably laced with humility.

FSJ: Who were some of the people you especially admired or were inspired by during your Foreign Service career?

RAD: There have been many people I have admired and sought to emulate during my Foreign Service career. In fact, it is the quality of the people I had occasion to observe and work and interact with that proved to be the most stimulating aspect of my Foreign Service experience. I would, however, cite three mentors who stand out because they embody the essential ingredients of a successful diplomat.

I will always be indebted to the late Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs Mary A. Ryan, who shared her advice, her counsel and her insights more generously than any other person I know. As a consular officer, she cared about the security and welfare of Americans living, traveling and studying abroad. She also cared about sharing America’s message and America’s freedoms, while at the same time protecting America’s borders and essential security. But most of all, she loved the Foreign Service, the work of the Department of State and the people who represent America overseas, and she looked after all three.

In terms of career achievement, Ambassador Terence A. Todman was always my polestar. He taught me to strive for the best and to be conscious of my responsibility to make the Foreign Service more inclusive of the American population. He came to the Department of State when segregated dining facilities were in vogue and when no career African-American Foreign Service officer was considered for worldwide assignments. It was next to miraculous that Todman broke the assignment color barrier, always excelling, both overseas and domestically, to become only the 33rd officer in the history of the Foreign Service to be named Career Ambassador.

And finally, in terms of institutional impact, there is Ambassador Edward J. Perkins, the first African-American Director General of the Foreign Service, who played a pivotal role in pressing South Africa to end apartheid and who, as DG, instituted the Pickering Fellowship program that is essential to the department’s diversity efforts. He taught me, above all, that one person can have a lasting institutional impact.

Successful diplomats must have integrity, courage and self-confidence, preferably laced with humility.

FSJ: How would you describe Civil Service–Foreign Service relations, and what changes have you seen over time?

RAD: Civil Service and Foreign Service relations continue to be a work in progress, complicated by two different personnel systems with different benefits, protections, rights, and appointment and promotion policies. I am in agreement with Secretary John F. Kerry that each component of State’s workforce must work together as one cohesive and vibrant team, which to me means a strong Foreign Service and a strong Civil Service working in unison to achieve U. S. foreign policy goals and objectives.

As Director General, I made every effort to strengthen both systems, especially through the Diplomatic Readiness Initiative, by increasing Civil Service hiring, training and assignment possibilities and re-engineering the Foreign Service hiring process. It is essential for the department to continue developing the potential of employees in both systems. I am particularly pleased with Director General Arnold Chacón’s new Civil Service Reform Initiative, which is designed to develop and enhance the career paths of entry- and mid-level Civil Service employees.

FSJ: Is the Foreign Service as an institution strong today? How has the role of the Foreign Service changed?

RAD: The Foreign Service as an institution could be stronger. A good beginning would be to dedicate additional resources to support our domestic and overseas operations.

But there’s more to be dealt with, such as questions about staffing, including the encroachment of Schedule Cs; the lack of understanding of the department’s role by the White House—witness the exponential growth of the National Security Council, which seems to me a duplication of State’s function; the lack of appreciation by Congress of the role of the Foreign Service, which is further marred by partisanship—a low point being the Benghazi hearings that ignored Congresses’ responsibility to provide the resources required to keep our people safe overseas; and, finally, a lack of understanding by the American public of what the Foreign Service does.

Moreover, as retired Ambassador Charles Ray is known for saying: FSOs need to exercise more courage in stepping up to the plate on issues like pushing for a career-long ‘education and training’ system to complement the training they currently get. And they need to adopt a formal code of ethical conduct for the Service as a means to inculcate professionalism in entry-level officers and reinforce it throughout a career.

I do not believe the fundamental role of the Foreign Service has changed, but the exigencies of today’s world demand more of modern diplomats. With the proliferation of terrorist groups, physical security is a major concern, especially overseas; moreover, protection of the homeland is the uppermost thought of all visa officers. Diplomats must now pay serious attention to information technology, especially cybersecurity—not to mention the prominence of environmental issues, transnational health issues, refugee flows, and issues of war and peacekeeping. The list goes on, all calling for diplomacy at the highest level.

FSJ: Are you optimistic about the future of professional diplomacy?

RAD: Yes. I believe that in this global world of increasing complexity, crisis and challenges, professional diplomacy becomes ever more indispensable. However, the methods and means of practicing diplomacy must evolve to enable it to remain a leading force in sync with the demands of our changing world.

FSJ: How do you advise young people considering a Foreign Service career?

RAD: I relish recruiting for the Foreign Service and tell promising young people that our country desperately needs people with their values, intelligence and education. I do not sugarcoat the many challenges of a career in the Foreign Service, but tell them honestly that it offers a unique opportunity for public service that makes a difference in issues with global impact.