Climate Change: It’s Personal

As climate change boosts the frequency and severity of natural disasters, diplomats will increasingly find themselves dealing with the fallout.

BY KOVIA GRATZON-ERSKINE

Figure 1. Twenty-five countries and territories with most new displacements in 2020.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

Iam no stranger to fire. I have been posted overseas driving past burning buildings during riots or through roadblocks with stacks of burning tires and rock-throwing protesters. What I had never experienced until the fall of 2020 was an out-of-control forest fire, sweeping through a drought-ridden valley, taking out homes and old growth forest, and threatening the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands.

At 3 a.m. irksome chirps from my cell phone woke me. The alert: “Phase 2: Be ready. Stand by for evacuation orders.” Not wanting to wake my parents whom I was visiting in Oregon, I quietly began packing what I considered most crucial: grandma’s writings and instruments, family photographs, papers from my dad’s adoption, my passport, electronics, some clothes and creative projects. I filled gallon jugs of water and stashed away Clif bars, trail mix and Gatorade.

At 5 a.m. the sound of clanking metal and heavy tires sent me out to the usually quiet rural road. There, recreational vehicles and trucks full of livestock, tools, tractors and anything else that could fit barreled through the dark morning. These people reacting to “Phase 1: Leave now” lived a mere 20 minutes away. I woke my parents. “Time to pack,” I said. “Take what you can’t imagine losing.”

By 8 a.m. the kitchen table had turned into evacuation staging. I grabbed pillows and blankets. Barely a week out of surgery, my mother could hardly get out of bed. While she packed one small bag, I collapsed her walker, bed bolsters, shower chair, makeshift toilet, medicines and ice machine. My dad packed his CBD products for arthritis and SSRIs for depression and anxiety. “How long are we going to be gone?” He wanted to gauge how much dog and cat food to bring. “Is that right?” he asked, pointing to the clock. It said 8:30, but outside it was dark as night.

At 9 a.m. the sky was red. I rushed outside to look for fire. The smoke made me cough, and I ran back in. “Time to go. Dad, get the animals; I'll get Mom.” White ash fell as I packed the car, stuffing my parents in among our belongings. We headed out of town away from the fire, up the hill and out of the smoke-filled valley.

30.7 million people were newly displaced as a result of natural disasters in 2020.

Climate change is personal, but it is also communal. The year 2020 rivaled 2016 as the world’s hottest recorded year. The Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters recorded 389 climate-related events, resulting in more than 15,000 deaths and 98.4 million affected, according to U.N. Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (undrr.org). Climate change has been proven to make some hazards, such as wildfires, in certain regions more frequent and intense. Although not all weather-related disasters are a result of larger trends, the last two decades have seen a dramatic rise in disasters, including events linked to climate change.

In rural Oregon, we had an alert system. The public could view maps on air quality, flame coverage and burn damage. My family had a car and money to take us to safety. Thousands of volunteers collected clothes and toiletries, medicine and pet supplies for families that had lost nearly everything. The government and private sector opened hotel rooms and fairgrounds, providing safe havens for those displaced by the wildfire.

This is not the case for the 30.7 million people newly displaced as a result of natural disasters in 2020 (see figure 1). Natural disasters in the form of fire, drought, flood, earthquake, mudslides and other weather events affect the availability of clean water, food, livelihood options and shelter, forcing people to leave their homes (see figure 2).

In practical terms, this means there will be increased need for humanitarian assistance, development assistance and climate change diplomacy to support governments in promoting recovery, mitigating and adapting to climate change, establishing warning systems and developing emergency protocols. It means doing what we can to promote disaster risk reduction (remember: Oct. 13 is International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction).

In Guatemala, where I live now, the risks of natural disaster are plentiful. The country is ringed with gorgeous volcanoes, and tropical storms regularly roll in from two coasts, pouring down on communities that constantly manage the extremes of both drought and flood. This is a place where people brace through storms and listen to deep thunderous grumbles from nearby mountains in what are either resilient or adaptive behaviors. Those, however, who lose homes, land, crops and livelihoods are environmentally displaced, seeking refuge and a future for themselves and their loved ones.

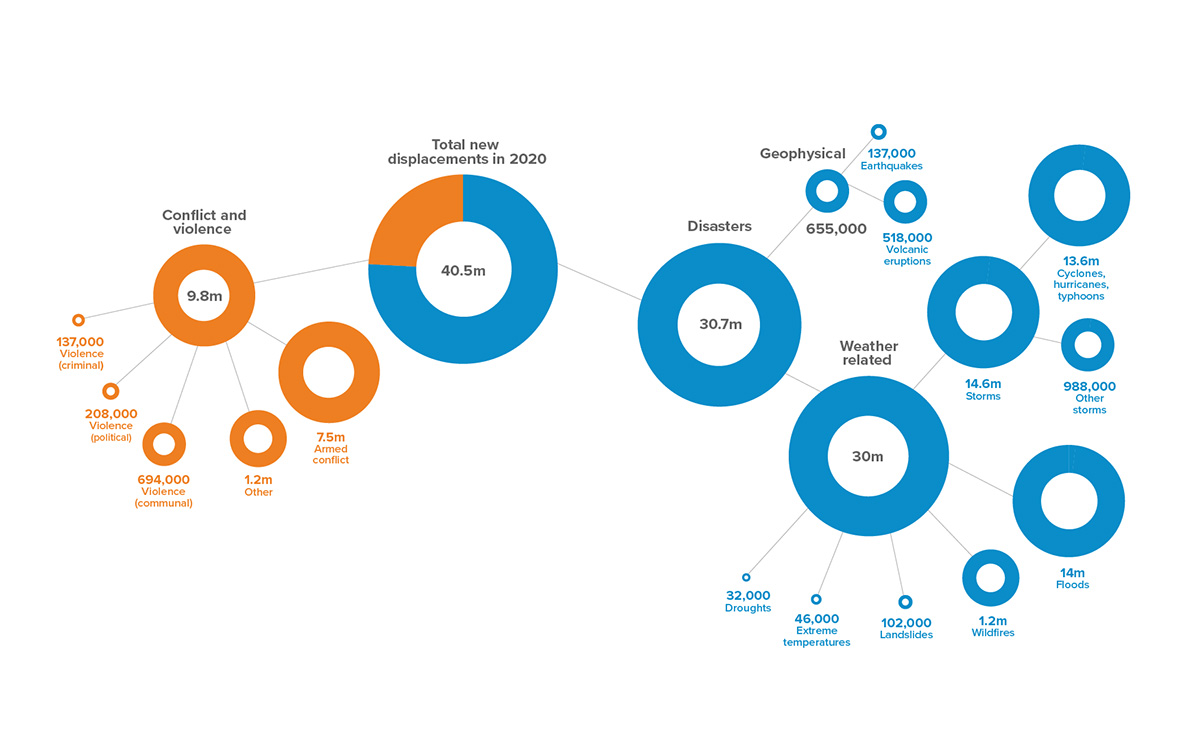

Figure 2. New displacements in 2020: breakdown for conflict and disasters.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

Checklist: When Things Get Hot at Work

Self

How’s my nervous system?

- Jumpy, irritable, sad vs. calm, grounded, content

How do I spend my day?

- Mostly at work or working vs. carving out time to do healthy and satisfying activities

How am I sleeping?

- Can’t fall asleep, can’t get out of bed, nightmares, tossing and turning vs. sleeping like a log

Others

Who can be an accountability buddy?

- Someone who can check in with me about quitting time, working after hours

- Someone who can encourage me to take a break, have fun, seek support

Agency

How can I take advantage and promote the use of agency policies and programs?

- Call Staff Care Center hotline 24/7

- Utilize available sick or annual leave

- Negotiate work schedule and plan with supervisors to promote work-life balance

More and more people around the globe are experiencing “solastalgia,” defined as the distress caused by environmental change. I would include myself. The distress can come in many ways: depression and anxiety over personally experiencing or lamenting certain changes, strong emotions over observing and working with and for populations directly affected by climate change, or disappointment over policy or programs that seem to take too long to make a real difference.

As climate change boosts the frequency and severity of natural disasters, more diplomats and development workers will find themselves unexpectedly part of a nation and living among communities grappling with recovery and, later, how to “fix” the issue. Helping people survive and helping governments and communities respond and build can lead to traumatic consequences not only for the people directly affected but also for those who support diplomacy and humanitarian and development assistance work. I have experienced nightmares, apathy, helplessness and hopelessness, depression and anxiety, even panic.

Well known among trauma and disaster professionals are three factors that increase the risk of experiencing traumatic consequences: duration, severity and meaning.

- Duration: working long hours for extended periods of time without stopping to eat, exercise, play, pray, socialize or otherwise recharge;

- Severity: being exposed constantly to death/dying, poverty, suffering, abuse and any horrific scene; and

- Meaning: connecting personally with the situation, being consumed by thoughts (“If I stop, someone will die or get hurt”).

I have found this to be true each time I dealt with a disaster on the job. Now I know that, I must consider my work habits and work environment (see sidebar).

The reality is that climate change—which includes assisting with disaster recovery, rebuilding communities and resolving policy issues to help the millions of environmentally displaced persons in this world—is a long-term, complex issue that requires solutions beyond the work of one person.

My Oregon wildfire trauma was short-lived. The situation couldn’t get more personal and meaningful. But my childhood home is still standing, and my parents are safe. For millions, this is not the case; and for diplomats and development workers, more and more will be faced personally or professionally with climate change and environmentally displaced persons. It will take not only a special kind of climate change diplomacy and post-disaster development expertise, but exceptional self-awareness and management skills to keep our staff healthy and safe, especially when things get hot.

Read More...

- “An Existential Threat That Demands Greater FS Engagement,” by Tim Lattimer, The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2017

- “It’s Time to Put Climate Action at the Center of U.S. Foreign Policy,” by Jason Bordoff, Foreign Policy, July 27, 2020

- “China’s Fight Against Climate Change and Environmental Degradation,” by Lindsay Maizland, Council on Foreign Relations, May 19, 2021