An Indomitable Spirit: Johnny Young, 1940-2021

BY JOEL EHRENDREICH

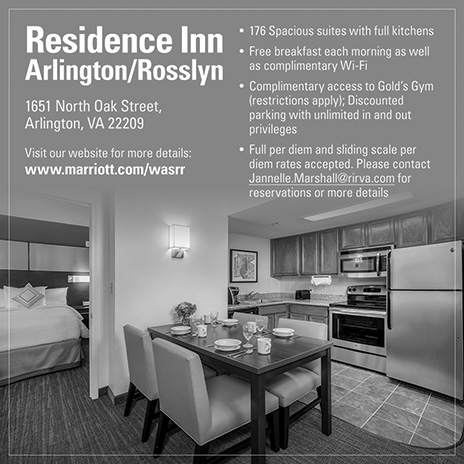

Johnny Young in 2014, 10 years after he retired from the Foreign Service.

Temple University

Johnny Young was the ambassador when I arrived for my first tour in Lome, Togo. That he would, during that tour, save my career when it could have been over so quickly is another story. Suffice it to say that the way he risked his reputation to save mine—when he didn’t have to—was the true definition of mercy, which Johnny’s life personified.

Indeed, for all who knew Johnny, we remember him first not for his exceptional career accomplishments; we recall his humanity, his dignity, his love for people of all nations and backgrounds, and the lasting impression he made on everyone. Together with his loving partner of more than 50 years, Angie, Johnny ran embassies that welcomed not just the employee, but the whole community.

I recall the large Thanksgiving party the Youngs threw in Lome, where our two pre-K children dressed up as turkeys for the play. A few nights later, it became clear how much of an impression Johnny and Angie’s warmth made on our 3-year-old son, Cooper. As we read Chicken Little to him before bed, at the point where Henny Penny says, “We must go tell the king!” Cooper corrected my wife: “No, mommy, we must tell the ambassador!”

Fast forward from that little boy to today. A couple of days after Johnny passed, Cooper joined a dinner with us and another Foreign Service couple who had never met the Youngs. He described Johnny and Angie like this: “After I graduated from college and moved here to start my career, Johnny and Angie heard I was in town and insisted on having me and my girlfriend, now wife, over for dinner. Why they felt they should open their home to children of people they worked with 20 years earlier amazed me. But I tell you what I remember most, is that when I was there, in their presence, there was an aura about them that you could just feel. Only one other time have I experienced such an aura when I was around someone, and that was when we got to meet the Dalai Lama in India. Johnny was just that powerful a force.”

Johnny Young’s autobiography is titled From the Projects to the Palace: A Diplomat’s Unlikely Journey from the Bottom to the Top. His journey was most unlikely, indeed. If Vegas odds-makers were to have looked at Johnny when he was growing up in an impoverished Black family in Georgia in the 1940s, they would have given him a zero percent chance of becoming a Career Ambassador. “We had nothing,” Johnny says in the book. “We were as poor as one can be. … We had difficulty with the Ku Klux Klan, and they would come to our street and absolutely terrorize us. I remember my mother would hold us close to her and with her hand over our mouths so that we wouldn’t make a sound.” (The mother referred to in this quote was his aunt, who raised him after his biological mother died of heart problems when he was but 1.) And in 1940 the United States was still more than two decades away from having its first African American ambassador.

It wouldn’t have just been gamblers who dismissed his chances for success. Johnny moved to the housing projects of Philadelphia at age 11. His attempt to enroll at the nearby, all-white Catholic school was rejected. “No, we don’t want them here,” the priest said, awakening Johnny for the first time to the savagery of racism. Despite eventual academic success, and ambitions of attending college, when he asked his high school counselor what he should do after graduation, he was told to “take a job in carpentry or something”—because “no college in its right mind will take a look at you.”

Johnny struggled to find meaningful employment: “I began to realize that I’d be called in for jobs, and the minute I walked in the door I knew that it was because of my color that I wasn’t going to get the job.” He eventually earned a certificate in accounting from Temple University and, later, a bachelor of arts magna cum laude; and he worked as a junior accountant for the city of Philadelphia. But it was a trip to Beirut as a delegate for the YMCA in 1965 that would change his life, exposing him to different cultures and convincing him to pursue a career in international affairs.

Johnny discovered the Foreign Service and passed the exam in 1967. Still, the odds were stacked against him. “You have to keep in mind that when I came in in ’67, you could count on one hand—not even two—the number of Black officers in the Service,” Johnny would recount.

Johnny ran embassies that welcomed not just the employee, but the whole community.

Characteristically, Johnny’s diplomatic career started humbly. Johnny and his lifelong love, Angie, were newlyweds when they boarded a steamer for a two-week voyage to their first post, Madagascar. During that first tour, when a diplomatic pouch he was the non-pro courier for temporarily went missing, Johnny thought: “Oh my God, this is the end of my career. It hasn’t even gotten off the ground yet.” Colleagues helped recover the pouch, and stuck out their necks to make sure he wasn’t made a scapegoat. It was an incident that would shape him, and he endeavored to return the favor throughout his career.

His next assignment was in Guinea, where he was caught up in the attempted coup against President Sekou Toure’s regime. Taken at gunpoint from his apartment and put in jail, he endured pressure to sign a forced confession. It wasn’t until the U.S. government threatened to end food aid to Guinea that he was released.

He advanced to midlevel assignments primarily in the administrative—as it was called at the time—cone, including Nairobi, Doha, Bridgetown, Amman and The Hague, in addition to tours in Washington.

In 1989 he was confirmed as U.S. ambassador to Sierra Leone. He would go on to be a four-time ambassador, also serving as the U.S. president’s representative in Togo, Bahrain and Slovenia. In 2004, he was awarded the rank of Career Ambassador.

Johnny Young’s prowess as a diplomat was recognized by peers and made him a role model for those who served under him. As his deputy chief of mission in Lome, Terry McCulley, recalls: “Johnny was beloved for his kindness, gentle manner and good humor, but he was also a fierce defender of American values. Togo’s President, Gnassingbe Eyadema, had been in effective power since 1963, and his security forces had pushed back brutally on efforts to open Togo’s political space, including firing on unarmed demonstrators and disappearing political opponents. Johnny was fearless in calling this out and firm in his private discussions with senior Togolese officials.”

“Eyadema was not used to this kind of pushback from American diplomats,” McCulley continued, “and during a meeting in his natal village of Pya with Ambassador Young and the visiting Africa Bureau principal deputy assistant secretary (as DCM, I was the notetaker), Eyadema asked for a private session with the Washington visitor. The PDAS told us immediately afterward that Eyadema had complained bitterly about Johnny’s actions and asked that Washington direct him to moderate his behavior. To his credit, the PDAS told the Togolese leader that Johnny was doing his job as the president’s personal representative and had Washington’s full support.”

Dean Haas was DCM in Ljubljana for much of Johnny’s final ambassadorship. “My memories of Johnny are all about his warmth, his friendliness and his ability to connect. He taught me and others how to get to the next level in getting to know people and showing you care. What I noticed after a few weeks in Ljubljana was how in touch he was with the staff—he knew about the lives of the people who worked for him, making no distinction between the American and Slovenian staff. Johnny is a leader I always recall when engaged now in coaching and mentoring. His legacy is a legion of people who have basked in his glow, learned from his experience, and tried to model his humanity and faith in his people.”

One of his co-pioneers in the Foreign Service, Aurelia Brazeal, described Johnny’s professionalism this way: “Johnny had an unerring way of focusing attention onto the crux of issues and, because of his intellect and forceful but unpretentious personality, getting consensus in most cases. A consummate host, as a diplomat he placed the foreign official (or whoever the visitor was) at the center of his attention, frequently compelling more revelations. He listened and crafted questions based on what was being revealed, thus learning substantially more from even a casual interaction.”

After retiring from the Foreign Service, Johnny relished the time with his children, David and Michelle, and his grandson, Phoenix. He stayed busy, becoming a private consultant, contractor and lecturer. He was appointed executive director of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2004, a position he held until just before his death.

But more than the numerous, odds-defying accomplishments, it was Johnny’s effusive happiness that endeared people to him most. Johnny would always say that despite the many challenges he faced growing up, he grew up happy. His humility, his grace, the joy he spread, his determination to pay it back and pay it forward—that is what defined him to the people he met. His partnership with his beloved Angelina reinforced all these qualities, and our thoughts go with her as she endures the loss of the love of her life.

Goodbye, ambassador, Mr. Career Ambassador. Goodbye, mentor. Goodbye, role model. Goodbye, friend. Goodbye to that special aura that was an inspiration to literally thousands around the world. I’d close by saying rest in peace, but you always seemed at peace; indeed, you were the source of peace. Instead, I’ll say thank you. The world is a better place with the energy you brought it.

Goodbye, Johnny.

Read More...

- “Johnny Young – From Abject Poverty to Chief of Mission,” by ADST

- “Interview with Ambassador Johnny Young,” by ADST (Full interview)

- “When will we learn… Drawing public and private lines in the sand?” by Amb. Johnny Young, American Diplomacy, September 2016