The Man Who Crossed the Seas: Charles Lindbergh’s Goodwill Tour, 1927-1928

A complicated and controversial public figure, Charles Lindbergh was also one of the first cultural ambassadors for the United States, as seen in his ambitious Latin America journey.

BY JAY RAMAN

On Dec. 12, 1927, the day before taking off on his Goodwill Tour, Charles Lindbergh looks over railroad maps for navigation over land during his flight.

Rand McNally and Company

Few Americans have left as complicated and confounding a legacy as Charles Lindbergh. He was the hero of his age but tarnished his reputation with his outspoken isolationist, racist and anti-Semitic views in the leadup to World War II. Today, he is remembered as much for his discredited politics as his daring aviation skills.

But for all his flaws, Lindbergh was undeniably a pioneer, and not just in the cockpit. He was a conservationist, a Pulitzer Prize–winning author and an inventor.

He was also one of our nation’s first cultural ambassadors.

The Goodwill Tour

The first three decades of the 20th century saw U.S. soldiers and ships deploy to Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Venezuela and most of Central America. This was a direct result of President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1904 corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which declared that the United States had the right to intervene in the internal affairs of its southern neighbors.

By 1927 the Roosevelt Corollary had run its course and the United States was eager to recalibrate its relationship with Latin America. In this context, U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Dwight Morrow hit on the idea of inviting Lindbergh on a “Goodwill Tour,” starting in Mexico City and continuing around the Caribbean Basin.

That May, the 25-year-old Lindbergh completed his famous solo flight across the Atlantic, departing New York a humble airmail pilot and arriving in Paris a global superstar. He was suddenly the most famous and admired man in the world, and when he agreed to Ambassador Morrow’s request, it must have seemed like a gift from the heavens to U.S. policymakers.

For Lindbergh, the Goodwill Tour was a chance to use his celebrity for good. In a preview of his trip for The New York Times, he wrote, “Although my primary interest is to visit the country as an aviator, I also hope that the flight will show the way in which aviation brings the peoples of the world together in better understanding of each other.” In that respect, Lindbergh’s trip had all the hallmarks of a modern-day cultural exchange, with his airplane providing both the ends and the means to foster people-to-people relations.

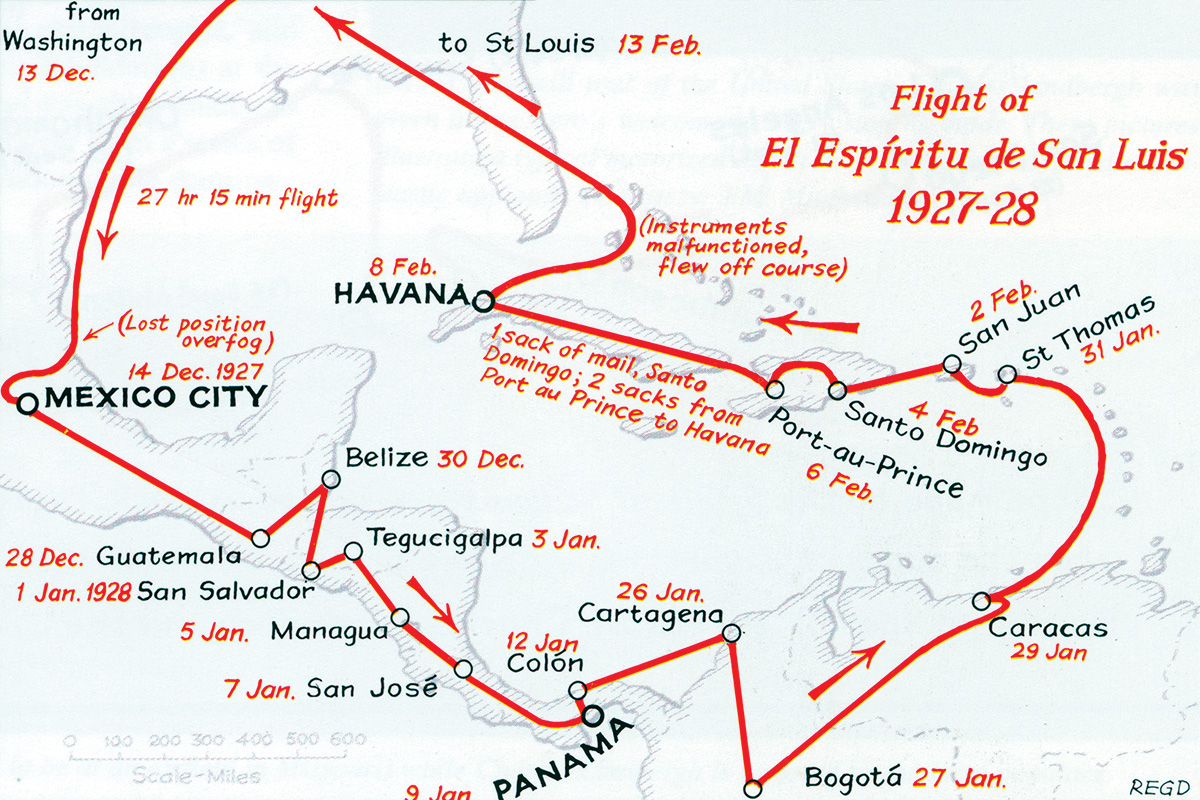

On his 9,500-mile tour, Charles Lindbergh flew from Washington, D.C., to Mexico, Guatemala, British Honduras, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Haiti and Cuba.

National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

The God of Wind

The trip got off to a bumpy start. On Dec. 13, Lindbergh took off from Washington, D.C., in the Spirit of St. Louis and headed southwest following landmarks and railroad tracks. He eventually became lost over Mexico, which lacked the visual markers common in the United States. He finally spotted a hotel sign in Toluca and reoriented himself, touching down in Mexico City 27 1/4 hours after departure. It was the first nonstop flight between the two capital cities.

Lindbergh was greeted by an enormous crowd including Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles, who declared a national holiday and ordered businesses to close. Lindbergh visited the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and attended a session of the Mexican Congress. He was celebrated at every occasion and took dignitaries on demonstration flights. More important, Lindbergh was introduced to Anne Morrow, the ambassador’s youngest daughter. The two were smitten and would marry in 1929.

Spending a total of two weeks in Mexico, Lindbergh was met with enthusiasm on both sides of the border that reached a fever pitch. On Christmas Day, the Times published a letter to the editor suggesting that Lindbergh might be the reincarnation of Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec god of wind. “May not this young man uplift the thought and crystallize the sentiment of Mexico?” the author asked rhetorically.

Clearly, the Goodwill Tour was working.

The Basis of Good Relations

Departing Mexico a hero, Lindbergh spent the next month hopscotching down the spine of Central America. The Times provided glowing coverage throughout, with correspondents filing anxious reports from every destination, supplemented by dispatches from Lindbergh himself.

Lindbergh was impressed by the sights along the way. As F. Robert van der Linden of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum notes: “All along his trip, Lindbergh was stunned by the natural beauty of the region and keenly aware of how undeveloped the transportation networks were—ideal territory for aviation, which could fly over the natural barriers of geography.” Lindbergh was also touched by the kindness he received, noting at one point that “the hospitable people of Guatemala are making it very hard for me to keep my visit here down to the two days which the schedule allows.”

The reserved Lindbergh was pressed into action as a citizen diplomat. Nicaragua was engulfed in a civil war and occupied by U.S. Marines, forcing Lindbergh to adjust his flight path to avoid conflict areas. But the members of Nicaragua’s rival political parties set aside their differences to attend a ball in Lindbergh’s honor. Lindbergh saw this—perhaps too optimistically—as “the best evidence that Nicaragua welcomes American aid in terminating the disorders which have recently disturbed Nicaragua.”

For Lindbergh, the Goodwill Tour was a chance to use his celebrity for good.

Throughout his trip, Lindbergh was an advocate for air travel. In one of his reports, he wrote, “I hope that commercial aviation will soon be able to help to provide rapid and safe communication for transport and travel, which is the basis of good relations.” From Costa Rica, he wrote, “My flights in this part of the world have indicated that aviation is one of the best available means of transportation and, in addition, that it is peculiarly adapted to Central America. Trips of days, if not of weeks, by the present means can be shortened to hours.”

Lindbergh spent more than two weeks in Panama, recovering from his rigors of the past month. His agenda was the subject of media speculation, and his American hosts in the Panama Canal Zone went to great lengths to shield him from the spotlight, saying that he “is very nervous and ‘may crack under the strain’ of social activity.”

When asked about Lindbergh’s hunting exploits, a companion cheekily responded, “He shot at a couple of wild pigeons on the wing, but missed them. So far he has not killed anything but time.” Spirit also received some much-needed attention, getting a complete overhaul by mechanics.

Rested and refreshed, Lindbergh lifted off from the isthmus on Jan. 26, 1928, and headed 400 miles east-northeast across the Caribbean Sea to Cartagena, his first destination in South America.

Pilots Will Come

Modern-day Colombia would not be possible without the airplane, for its mountains and jungles make transportation exquisitely difficult for the uninitiated. In April 1536, Spanish conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada left coastal Santa Marta for the interior with 800 soldiers. When he arrived at the future site of Bogotá a year later, only 162 were left. For the next four centuries, travel from the coast to the highlands required days of exhausting travel by riverboat and rutted tracks. Many places were completely isolated. Even today, terrestrial travel between large cities is often impractical, if not impossible.

The first few efforts at fixed-wing flight were a failure, but Colombians pressed on. As one hopeful enthusiast wrote, “Pilots will come. The devices will be among the best known today. We predict true triumphs and magnificent results for the one who comes to bring us that little bit of civilization.”

American pilot George Schmitt is credited with bringing aviation to Colombia in 1912, making it as far as Medellín. The Andes proved a formidable barrier, however, and it would be another six years before the first plane came to Bogotá.

Lindbergh’s trip had all the hallmarks of a modern-day cultural exchange, with his airplane providing both the ends and the means to foster people-to-people relations.

Airplanes of that era were not equipped for high-altitude conditions, leaving pilots exposed to the elements. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s 1939 memoir, Wind, Sand and Stars, recounts the experience of pilots flying early mail planes through similar mountain passes in Argentina and Chile, where “blustering gusts sweep through the narrow walls of their rocky corridors and force the pilot to a sort of hand-to-hand combat.”

Despite the risks, Colombians were quick to embrace the new technology. Colombia’s first airline, Sociedad Colombo-Alemana de Transportes Aéreos (SCADTA), was founded in 1919, and within a few years it was already traveling to Venezuela and the United States. SCADTA eventually merged with another company to become Avianca, which is considered the second-oldest continually operating airline in the world (after KLM).

By the middle of the century, domestic routes stretched from the Atlantic and Pacific coasts into the mountainous interior and south to the Amazon. Air travel had accomplished what nothing else could: It made Colombia whole.

My Motor Does Not Fail

Lindbergh was supposed to fly straight to Venezuela, but at the last minute he decided to include Colombia in his itinerary. Working on short notice, a contingent of officials, including the American consul, gathered in Cartagena to await his arrival. The crowd grew steadily over the course of the day, and by the time the plane came into view, it had broken through the police cordon and swamped the landing grounds. Lindbergh had to circle the field four times to clear enough space to land.

When he touched down, Lindbergh was mobbed by well-wishers, “necessitating his rescue by numbers of his compatriots, who bore him to the reception stand.” On the way into town, “the procession passed through the principal streets en route, gaining in volume at each block until it developed into the largest assembly ever witnessed in Cartagena. Upon arrival at the Cartagena Club champagne was partaken of,” though presumably not by Lindbergh, who was known for his temperance.

Lindbergh spent one night there hosted by an American official of the Andean National Corporation, a subsidiary of the Standard Oil Company. The inevitable banquet and ball included renditions of “Lucky Lindy” and “Lindy”—two of the hundreds of songs about Lindbergh that were copyrighted between 1927 and 1929.

As was his custom, Lindbergh had nothing but praise for the city and its people, saying, “Cartagena, seen from the air, is the most beautiful city of all those … so far visited.” As he readied for departure, the reporter asked if Lindbergh was concerned about the surrounding mountains and fog. “My motor does not fail,” was Lindbergh’s retort.

With that, Lindbergh climbed back into Spirit and set off for Bogotá.

Flags from the countries Lindbergh visited, on the hull of his plane.

Mike Peel

A Hearty and Enthusiastic Reception

Unlike Cartagena, Colombia’s capital was fully prepared for Lindbergh’s arrival. The American legation, under the direction of Minister Samuel Piles, worked feverishly with the Colombian government to arrange a proper welcome.

Lindbergh navigated his way from Cartagena by following the San Jorge River and then connecting with the Nechí and Cauca Rivers, which took him to the town of Puerto Berrio. From there, he ascended high into the Andes, working his way through a pass at 9,800 feet. He dropped out of the clouds at 2 p.m., making several turns over the city before touching down at Madrid Field an hour later.

The Associated Press reported that Lindbergh “came from Cartagena, about 425 miles away, over high mountains enshrouded in clouds, past dangerous ravines, and through unknown country—one of the most daring flights he has yet made on his present tour. No other plane had ever crossed the ranges to the valley in which the Colombian capital lies, and Lindbergh was on time.”

On landing, the plane was swamped by a crowd of 15,000 and Lindbergh “seemed almost in danger of his life from the enthusiastic welcome.” A detachment from the aviation school rushed in to protect Spirit. After stepping down from the cockpit, Lindbergh “was greeting with a kiss on the cheek by Señorita Olga Noguera Davila, pretty queen of the student body delegated for this duty.” Not to be outdone, the “feminine contingent of the American colony” presented him with a feather, pearl and gold locket to take home to his mother.

“No other plane had ever crossed the ranges to the valley in which the Colombian capital lies, and Lindbergh was on time.”

As Lindbergh wrote in one of his dispatches, “The welcome by the people of Colombia at the Madrid Aviation Field might well be compared to that at Paris in May. It took nearly an hour, because of the enthusiasm of the people, to get to the aviation school building.” He then went a step further by saying, “I have never received a more hearty and enthusiastic reception in either America or Europe than the one today at Bogota.”

From the airfield, Lindbergh made the 20-mile trip into town “over a smooth road comparable to our own in the United States,” accompanied by Minister Piles and Colombian Foreign Minister Carlos Uribe. At the entrance to the city, the motorcade was joined by a mounted escort. They were also followed by hundreds of private cars, prompting one reporter to remark, “If any automobile in Bogota was not in the parade it must have been in the machine shop.”

Flowers and streamers poured down as Lindbergh waved politely from the back of the open car. A correspondent estimated that 100,000 people lined the streets to welcome Lindbergh to Bogotá. If accurate, that would have been almost half the city’s population.

The parade finally arrived at the American legation building at 6 p.m., where Lindbergh and Piles appeared on the balcony. Lindbergh gamely headed out to tea, followed by a late-night reception at the Anglo-American club.

Meanwhile, a colorful crowd lingered hoping for one last glimpse of their hero. As a reporter described it, “They were of all classes. Sandal-clad or barefoot Indian men and women of the country districts touched elbows with Bogota’s ‘nicest people’—a strange picture in contrasts, illuminated by many searchlights flooding the neighborhood of the legation.”

The Lone Eagle

Charles Lindbergh works on the engine of the Spirit of St. Louis in 1927.

Library of Congress

After a late breakfast and a meeting with reporters and fellow aviators, Lindbergh paid a courtesy call on Colombian President Miguel Abadía Méndez. The president presented Lindbergh with the Cross of Boyacá—the country’s highest military distinction, which had been awarded just nine times before and never to an American.

Lindbergh then went back to the airfield to inspect his plane, which had been topped off with gasoline and oil provided by the Colombian government. In the evening, Lindbergh attended a banquet at the legation for 600 guests. He was continuously called out to the balcony “to acknowledge, with the ‘Lindbergh smile’ very much in evidence, the prolonged cheers of the Colombians.” The banquet was followed by a ball at the Jockey Club, where Lindbergh was “serenaded until midnight.”

The next day, Lindbergh was up at the crack of dawn. After a final breakfast at the legation, he headed back to Madrid Field to ready the plane for departure. As the Times reported, “There he was surrounded by a hundred or more cheering Colombians, many of whom were in evening attire, having attended the dance given in his honor last night. High officials were on hand to bid him farewell and to express the wish that he would visit the city again for a more extended trip.

“The Spirit of St. Louis responded quickly to the turn of the propeller and rose gracefully from the field under the touch of her distinguished pilot. A few minutes later a silver speck high in the sky completely disappeared beyond the mountains and the ‘Lone Eagle’ was winging his way to another city that eagerly awaited his presence.”

When approached by a reporter at the scene, President Abadía Méndez offered a final tribute: “If Horace eulogized the man who crossed the seas, what can be said of the man who crosses the seas in the air?”

Postscript

Lindbergh’s journey from Bogotá to Maracay, Venezuela, would pioneer yet another route. The trip took 11 hours and required Lindbergh to fight his way back to land after being swept off course due to wind and fog. Despite the difficulty, “the supreme audacity which is Colonel Lindbergh’s birthright carried him through to another aeronautical triumph.”

He would go on to visit Caracas by car before flying to the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Haiti and Cuba. The last leg of the journey was direct from Havana to St. Louis.

Two months to the day after setting out, the Goodwill Tour had reached its end. When asked about future plans, Lindbergh said simply, “I have none beyond getting a good night’s rest and making my air mail flight next week.”

Read More...

- “Charles Lindbergh,” History.com, May 6, 2020

- “Germany and the America First movement,” by Encyclopedia Britannica

- “Lindbergh Kidnapping,” by FBI