Four Centuries and Three Decades of Russian Thinking

Conversations in Moscow with Russians of different social strata paint a vivid picture of a country grappling with the meaning of the past quarter-century's upheavals.

BY JUSTIN LIFFLANDER

People line up to purchase milk at a store in Syktyvkar, Russia, in 1989.

Shawn Dorman

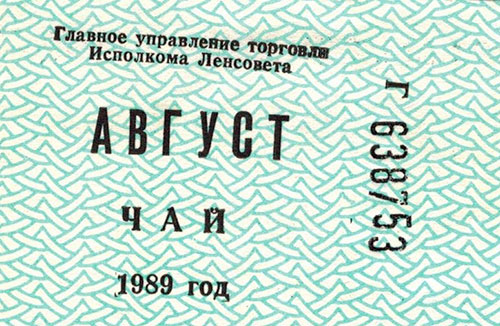

An August 1989 ration voucher for tea.

Shawn Dorman

At first it seemed to me as if he was wearing X-ray glasses. Having purchased a fur hat from Sasha, the teenage fartsovchik (black marketeer) working the Oktyabrskaya subway station in Moscow that day in 1986, I earned the right to chat with him in my broken Russian.

As he scanned the passers-by in search of potential clientele, I couldn’t figure out how he was able to spot the foreigners. “Look carefully,” he explained. “The facial features, the shoes, the wrist watches, the eye glasses. …” I began to understand how he chose who should be offered his znachki (pins) or money changing services.

Thirty years later my fartsovchik is probably a successful oligarch. He and his countrymen no longer think they are “covered in chocolate”—a phrase going back to the Soviet era meaning “fortunate, lucky, living well”—as they build the socialist paradise while the West rots on the garbage heap of history.

Living and working in Russia for the past three decades, I’ve become acquainted with people from a broad range of social strata—from government ministers to migrant workers. I turned to them to collect and distill their insights on how Russian thinking has changed since the end of the USSR.

The Evolution of Homo Rusicus

My friend Mikhailovich is a middle-aged entrepreneur who moved to Moscow from Kyiv as a young man. He believes that the factors contributing to an individual’s mentality are both experiential and hereditary.

“Look at the past 400 years. The Romanov dynasty started in 1613 and lasted 300 years,” Mikhailovich says. “The communists were in power for 74 years, and we’ve been free of them for 25 years. It is not a coincidence that 75 percent of the population are content to live under authoritarian rule; 24 percent think like communists—either thieves or despisers of private property and individual success; and only about 1 percent we can call ‘neo-Russian’—those with a balanced view of the external world and a desire to live and function in a progressive society.”

Street musician draws a crowd on Arbat Street, Moscow, 1988.

Shawn Dorman

Yurevich, another friend, has lived and worked in Moscow since completing his studies at the end of the 1980s. He puts the same idea another way, pointing out how long it takes for any society to free itself of the slave mentality: “About 150 years ago, Russia formally ended serfdom—the same time as the abolition of slavery in the United States. See how long the echo of distrust and low self-esteem lasts in both countries? And the slave belief that a man is unable to influence his fate has remained an element of the Russian soul since then. It helped the czars and the communists maintain power after emancipation…and is a big factor in the government’s popularity now.

“Periods of oppression followed one after the other,” continues Yurevich. “In 1917, the Communists destroyed the thin layer of society whose members had begun to raise their heads after the emancipation of 1861—the kulaki (wealthy farmers), the new intelligentsia and leading engineers. They were killed or compelled to emigrate, so the West got Sikorsky, Bunin and many others.”

“It’s in the Homo rusicus genes to count not on himself, but on someone from above,” Yurevich says. “He has had few opportunities to express his intellect and talents. As the poet Nikolay Nekrasov wrote, ‘The master will come and the master will solve the problem.’”

An engineer by training, Yurevich sees the lack of personal accountability as an explanation for the fact that Russian innovation rarely makes it to market thanks to a Russian. It takes determination born of a sense of ownership and responsibility to turn an idea into a product.

Perestroika, the effort to restructure the political and economic life of the country initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev in the mid-1980s, gave people a chance to open their eyes and start thinking for themselves. “But the only way to incubate a mentality of accountability and free-thinking is via the education system; and it’s not visible yet,” Yurevich adds. “Still, many people have learned to overcome the infantilism of the USSR and become responsible for their own fate.”

The More Things Change

The wave of capitalism rolled eastward in the 1990s, and the landscape changed forever. Fanatic consumerism is now unabated, as are the traffic jams—which often reach maximum density around shopping centers.

New creative art space with book shops, studios, galleries and educational centers at the Red October factory (former chocolate factory) in the center of Moscow, February 2016.

Arthur Bondar

But many average Russians were washed overboard in the torrent. Even those who find success and happiness in post- Soviet Russia are nostalgic. Beyond getting used to the new perceived reality of poor-quality, high-priced “public” education and health care, there are changes in the very fabric of society. Gaping sinkholes in the mental landscape have appeared. Beloved traditions have disappeared out of reach forever. Friendships are harder to form—there is less interdependence and less time. Discourse at the kitchen table has been replaced by a mind-numbing flat-screen TV and “googling” for answers.

Druzhba narodov (the friendship of peoples), which described respectful interaction between Russia’s ethnic groups in the Soviet era, took a nosedive as migrants began to compete with locals for jobs and social services. Tensions, real and imagined, flare on the borders and between nationalities. Families are divided across former republics by political maneuvering and military conflicts. At home, the dvor (apartment yard), with its herd of children banding together after school to explore territory and relationships, is now blocked off by a semaphore gate and occupied by parked cars and trash containers.

Filipovich, a retiree who emigrated to California a few years ago, fondly recalls the sense of wonder the average post-Soviet citizen experienced in the 1990s when foreigners shared elements of their high standard of living. A Snickers bar cut into a dozen slices could easily bring joy to an entire group of friends.

The bucolic but tipsy countryside, where doors went unlocked and a stranger could appear and count on room and board with no remuneration expected, is no more. Yevgenevich, a 45-year-old native Muscovite executive, says poverty and a sense of desertion have fostered cynicism and greed in rural Russia. Those who are able flee, migrating to the big cities in search of education, goods and jobs unavailable at home. Residents of regional cities fare better. But by and large, they are focused inward. They use their limited disposable income not for travel, but for apartment remodeling and buying consumer goods—often on credit.

The culture of leadership has changed, too. Petrovich, a retired government official in his seventies, laments a loss of accountability among the political elite. When Mathias Rust landed in Red Square in 1987, the defense minister and a dozen generals were fired, and no one was surprised. This year Russia’s reputation as a sporting power was decimated by a doping scandal, and the sports minister, a longtime friend of the president, got promoted. Today, power is based on a St. Petersburg pedigree and your historical ties to the inner circle. Though it was never much of a meritocracy, the political and industrial leaders of the USSR were from a far broader geographic base and had a far more restrictive code of conduct.

Meanwhile, the average Russian now believes that Mikhail Gorbachev was an agent of the Central Intelligence Agency. How else to explain the events that led to the end of a country as powerful as the USSR?

Daily life on Tretyakovskiy Proezd Street, Moscow, February 2016.

Arthur Bondar

Relative Political Freedom Has Its Benefits

But there are also developments feeding an authentic sense of pride. With the cult of the individual taking hold, Ayn Rand’s objectivist philosophy is no longer seen as an anti-lesson but rather as a model with a growing fan base. In typical Russian fashion, this cuts both ways. While some pursue goals, many are returning to the involuntary mindfulness of the USSR—living one day at a time, with no grand ambitions. This time it’s not the result of blissful state-sponsored ignorance, but reignited uncertainty about the future.

Despite the pendulum’s swing toward conservatism, including current draconian laws and official morality, many Russians are comparatively more liberal in their thinking about gender today than in the Soviet period. Several major cities have at least one underground gay club, which survives thanks to a national “don’t ask, don’t tell” mentality. And while in the USSR the only steering wheel behind which you could find a woman was that of a tractor or trolley bus, female automobile drivers are now a common sight on the road.

Political freedom is also a relative concept. One friend illustrates how people here perceive democracy using the joke about a couple celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary.

“How did you do it?” a guest at the celebration asks the husband.

“Simple,” he says. “When we got married she told me she never wants to have a disagreement, and proposed we divide our authority. I make all the big decisions; she makes all the small ones.”

“And how did that work out?” the guest asks.

“Great,” he says. “It turns out there has never been the need to make a big decision.”

Indeed, with the electorate cajoled into showing up at the polls, voting irregularities and a barely nascent concept of conflict of interest, the democratic landscape resembles that of the late 19th-century United States—which is significant progress over the Soviet period.

“Now, activists are running for office,” says long-serving State Department Kremlinologist Igor Belousovitch. “They are visible in the press, they are grudgingly recognized by the authorities. ... Who would have thought in the days [of the USSR] that opponents of the regime would be running for office and even joining legislative bodies?”

Freedom of worship, at least for mainstream religions, is another new concept that Homo rusicus has in his quiver to help compensate for his losses. The millennium anniversary of the Russian Orthodox Church in 1988, under the tolerant watch of the glasnost (openness) campaign, gave a kickstart to the rebirth of that religion. Now more than 70 percent of the population openly associates itself with orthodoxy, and the genuinely faithful can be found at all levels of society.

Looking Outwards

A young woman texts on the embankment in Sochi, Russia, February 2014.

Arthur Bondar

In the late 1980s, when not patrolling the subway station in search of the almighty dollar, Sasha the fartsovchik would collect and play games with fantiki—the colorful wrappers of imported chewing gum. During the era of glasnost and U.S.-Soviet peacemaking between President Ronald Reagan and General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, some began to think that “help from above”—formerly the exclusive role of the party and its leadership— might now be coming from the West.

Teens and young adults of the late 1980s and early 1990s began to get more access to Western goods and culture. The forbidden fruit tasted sweet. With the disintegration of the USSR, it wasn’t hard to conclude that communism had been a mistake. Many of that generation believed their government would learn from the West. Democracy was just around the bend.

This kind of zapadnichestvo (reverence of all things Western) traces its roots to Peter the Great, illustrated in the 1928 satirical novel by Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov, The Twelve Chairs. As the New Economic Policy–era collective discusses a way out of its dire economic straits, con man Ostap Bender chimes in with a typical Russian combination of sarcasm and faith, “Don’t worry. The West will save us!” This faith has not, however, been constant: the economic crises of 1991, 1998, 2008 and 2016 jolted some into doubting the sanctity of the world economic order and its worthiness as a role model. Yet my friend Yurevich remains optimistic: “In any case, we have become more broadminded, thanks to the flow of information.”

At the same time, this expansion of intellectual horizons has not been fully embraced by the government, since a freethinking citizenry is not an element of a monarchy or any of its authoritarian permutations. Yurevich offered an example: I had been taught that Stalin locked up many returning Russian prisoners of war because they were considered traitors for allowing themselves to be captured. But Stalin’s real fear, according to Yurevich, was that the soldiers might share their impressions of the Germans’ high standard of living.

The Door Is Ajar

Mikhailovich concurs that the door to the West is still only ajar. The volume of exchange is paltry. The neo-Russian minority— 1 percent of the population—has begun to travel the world as tourists, students and businessmen. The West has penetrated their souls, at least superficially. But only a sliver of the total populace has experienced this, or had the opportunity to interact with intrepid foreigners studying and working in Russia.

Thanks to subsistence-level salaries, labor market dynamics and registration rules, Russia remains a highly immobile society— especially for residents of the regions. The vast majority of the Russian population read about foreigners in books and watch foreign movies, but they have only a vague idea of how foreigners really live. The most mundane things can easily shock them. Lenochka, a young woman from central Russia, tells of the teacher from her provincial town who recently shared with the local paper her deep insight from a trip to Europe: how the aborigines (a Russian term for natives of other countries) are disciplined and throw their garbage into rubbish bins. The effort to separate items for recycling impressed her even more.

It was only natural that an element of resentment would emerge. Vladimir Kartsev, in his 1995 biography of populist politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky, tries to explain the phenomenon by asking the American reader to step into the shoes of his Russian counterpart living in post- Soviet chaos: “Imagine General Motors and General Electric have been bought and taken over by local sheriffs. Lockheed is producing pots and pans. … Texas is engaged in a bloody war with Arkansas. Hawaii, New Mexico and Alaska have declared independence and called for a jihad against the U.S. government. … All you can see on television are old Russian films and ads for Stolichnaya vodka.”

Now there is funding for domestically produced TV and film content. Anti-Western rhetoric has skyrocketed since the start of the current geopolitical rift. Meanwhile, more than half the population considers television the most trustworthy news source, according to a poll last year by the Levada Center, an independent research organization. And because people have little firsthand knowledge about foreigners, it is easy for TV producers to hop on the pendulum as it swings back against the West. In this way they impose their state-sponsored views: the West must be feared, Western people have crumbling morals, etc.

The barrage of “feel good” TV programming—where, as one pundit put it, “prosperity is a state of mind”—is having an effect. Economic and other statistics indicate a real decline in the standard of living.

Though it serves as a weather vane for the ever-present Russian duality, the pendulum casts its shadow only on the surface. Foreign is, was and always will be cool…at least in terms of gadgets, food and films. Still, the anti-West swing has a dangerous effect on the mindset. A 2015 Levada poll found that 31 percent of Russians believe the United States might attack their country.

The vast majority of Russians remain convinced of their country’s greatness: 25 percent believe that Russia is already a “great power,” and another 49 percent believe it will become one in the near future, according to 2016 Levada figures. Interestingly, in 2014 the “leading indicators” of this greatness in the minds of the respondents were the country’s “developed economy” and “strong military”— 52 percent and 42 percent respectively. Those factors have now dropped to 37 percent and 26 percent respectively. As of this year, 38 percent of respondents believe the country’s greatness is evidenced first and foremost by the “well-being of its citizens.” The barrage of “feel good” TV programming— where, as one pundit put it, “prosperity is a state of mind”—is having an effect. Economic and other statistics indicate a real decline in the standard of living.

The neo-Russians, for their part, don’t trust their televisions. They are uneasy. Another Levada poll in July revealed that 42 percent of 500 senior managers of domestic and foreign companies working in Russia want to emigrate. Meanwhile, the number of foreign specialists coming into Russia has declined dramatically, with information agency Ros Business Consulting reporting a 57-percent drop in work permits issued for “highly qualified” European executives in 2015 compared to 2013.

What’s to Be Done?

Dissecting the deception is the best hope for reaching the Russian mind, Yurevich says: “Our government wants the people to equate love for the motherland with love for the state. But the motherland is not the state: it is the people, the soil, the culture. The West should understand this and leverage it in each communication; differentiate every time there is a comment or criticism of the state. Don’t say ‘The Russians annexed Crimea.’ Say ‘The Russian government…’”

Mikhailovich remains calm, pours another cup of tea and points out that Russia’s relationship with the West must be looked at as an interaction between different civilizations. “We are just at the initial stage of getting acquainted. There are pain points in the process: high expectations on both sides. Those who have faith and a long-term strategy—in diplomatic, business and personal relations—are the ones who will succeed. Besides, don’t forget: it’s a pendulum. It swings back and forth.”

Mikhailovich’s thesis that 75 percent of the people need authoritarian rule explains President Vladimir Putin’s huge popularity. It is noteworthy that despite the herd mentality fostered by television and exemplified by gangs of rowdy soccer fans, Mikhailovich has such faith. He is convinced that if a brawling Russian were to break away from the mob and face his foreign counterpart as an individual, his façade of nationalism and bravado would quickly fall and the humility of his Russian soul would emerge…probably. Keeping in mind the more subtle elements of history and culture will help to facilitate understanding.

Tatyana, a 38-year-old professional, was born in the Urals, lived for many years in Moscow, but has since moved to Italy to escape the superficial materialistic suyta (fuss) that she says has possessed the capital city. She chose family as a metaphor for understanding mindsets. “Putin’s Russia is only 16 years old: a teenager—a boy, I think, with all the associated testosterone, insecurity and potential for development. The United States is the baffled, self-absorbed middle-aged parent, occasionally trying to find a common language. Then we have Grandma Europe: overindulgent, a bit clueless, but applying wisdom to her relationships.”

People enjoying Mayakovskaya Square in Moscow in February, after its renovation.

Arthur Bondar

Counting on Kolya

And finally, there is Cousin Kolya. In his mid-60s, Kolya lives in a village 150 miles north of Moscow. A professional fireman in the Soviet era, in the early 1990s he made his first trip to Poland to buy cheap Western housewares for resale back home. He built a business, bought a log cabin on a small plot of land and put his son through college. Now he and his wife focus on their vegetable garden, chickens and honey bees.

As stoic as the farmer with the pitchfork in Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” Kolya survives and thrives on self-reliance, faith in a higher power and a quasi-Tolstoyan philosophy of distrusting the state. Unlike Lev Nikolayevich, he enjoys meat and moonshine…in moderation. Like most Russians, a healthy respect for fate permeates his ideology.

“Do most Russians think differently now?” I ask him.

Kolya doesn’t hesitate. “No.”

“But what about you?”

“I had my own personal perestroika. Many people haven’t.”