Great Expectations

The administration’s vow to host the second U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit this year has sparked hope that Washington will treat Africa as a strategic priority. Here’s what’s at stake.

BY KENDRA L. GAITHER

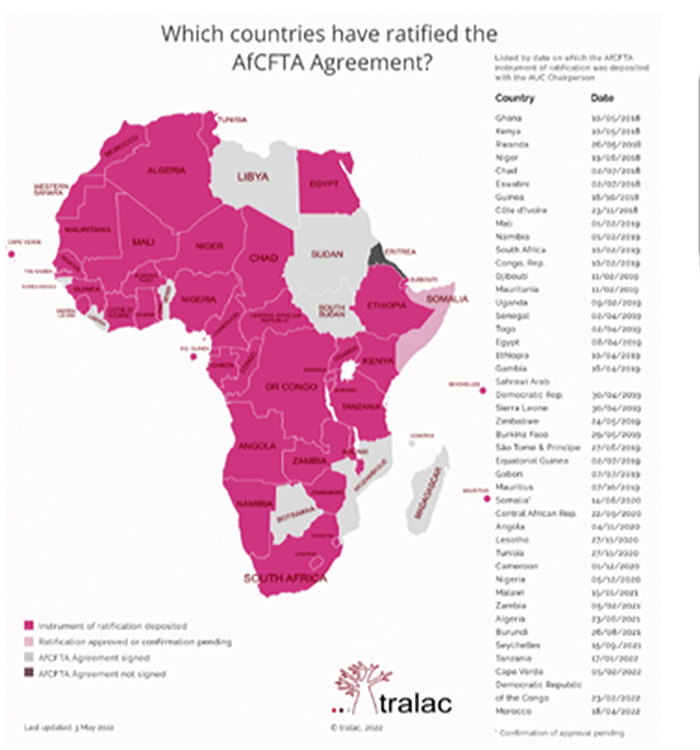

Trade Law Centre NPC (TRALAC)

On Feb. 5, 2021, a mere two weeks after taking office, President Joseph R. Biden delivered a video message to the African Union Summit, a convening of heads of state from the 55 member countries held virtually due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. President Biden said his administration would work to improve the relationship with the African continent based on mutual respect and solidarity “to advance our shared vision of a better future.” And the message was well received by African governments and institutions. In November, during his first trip to Africa as Secretary of State, Antony Blinken announced that President Biden would host the second U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit to deepen cooperation.

We at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s U.S.-Africa Business Center, the member companies we represent, and our network of affiliated American Chambers of Commerce across Africa enthusiastically welcomed Biden’s early signal and the Blinken announcement. The U.S. private sector, like others, had taken stock of U.S. foreign policy engagement with Africa and compiled a series of recommendations on engaging the African continent as a U.S. foreign policy priority. Topping that list was a call to reinstitute the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit and its accompanying business forum, and to demonstrate commitment to mutually beneficial trade and investment as part of an ongoing strategic partnership with the African continent.

The promised U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, scheduled for Dec. 13-15 this year, will be the first head of state gathering of African leaders and a U.S. president since 2014, and marks only the second time Washington has accorded this level of attention to a partnership dialogue with the region. Though the United States has an annual trade forum through the African Growth and Opportunity Act, convening trade ministers and a number of bilateral strategic dialogues with key country partners at the foreign minister level, these gatherings don’t confer presidential-level priority.

The hope now is that the summit will usher in more consistent head-of-state engagement, treat Africa as a strategic priority for the United States and give a dynamic boost to mutually beneficial U.S. engagement on the continent.

What’s At Stake

One need only look at the contemporary global issues that have dominated 2022 to understand the critical role the African continent plays today and how it will shape the future. South African scientists’ extensive and sophisticated genomic surveillance system was the first to identify and detect the Omicron variant of COVID-19 in a critical effort in the global fight to stop the spread of the virus. Africa represents 28 percent of the United Nations membership and has a significant voice in geopolitics. This was on display as only half of Africa’s 54 member states voted to rebuke Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and most of the remaining countries abstained.

As the world assesses its progress and makes new commitments in advance of the 27th Conference of Parties to the U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP 27) to be hosted by Egypt on behalf of the African continent in November 2022, Africa is classified by the United Nations Environmental Program as the most vulnerable region in the world to the effects of climate change, and it is also home to mineral resources like lithium, cobalt, palladium and others that are powering the green revolution and electric vehicles in the race for sustainability solutions.

The staggering demographic boom transforming Africa’s and the world’s future has been well covered, but it bears repeating when considering the opportunities and imperatives that other countries are reviewing and responding to with a clear vision. The African continent is home to approximately 1.3 billion people, with an estimated population growth rate of 2.7 percent—more than double that of South Asia (1.2 percent) and triple that of Latin America (0.9 percent). The United Nations projects that by 2050, Africa’s population will nearly double to 2.5 billion people, and by 2100 triple to 3.8 billion. These numbers are even more significant in light of the 2020 Lancet study that predicts every other region could see its population decline during this same period.

Africa also has an exciting new trade bloc, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), that unites the continent into a single giant market.

In other words, by the end of this century, one-third of the people on the planet will be African and largely concentrated in cities, with 65 percent of the top 20 urban areas projected to be on the continent. Nigeria, already the most populous African country, is expected to nearly double in population to 400 million by 2050, overtaking the United States as the third-most populous nation in the world, with Lagos poised to become the world’s largest city. The Brookings Institution also projects that by 2050, Africa’s combined business and consumer spending will exceed $16 trillion, making the continent an attractive market for African producers and global exporters alike. This means that a continent with the youngest population in the world will set trends in trade, technology, climate sustainability and urban development that will dictate the future of the planet. If demographics are destiny, then Africa is poised to be the center of global affairs within a generation.

Prior to the COVID-19 global pandemic, Africa was home to six of the 10 fastest-growing economies in the world. The United States has a growing two-way trade relationship with the continent that exceeded $64 billion in 2021, but this only represents 1 percent of U.S. trade, and there is plenty of room to grow America’s economic partnership with Africa as the continent continues to grow and attract global trade and investment. The continent that gave rise to mobile money and digital payments set record highs in 2021 for venture capital (VC) investments in its fintech sector, according to Partech’s 2021 Africa Tech Venture Capital Report. That report showed that African VC investments tripled from the prior year, grew faster than any other region and are growing three times faster than global VC investment. Africa also has an exciting new trade bloc, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), that unites the continent into a single giant market and promises to reduce red tape, harmonize the regulatory burden, and significantly diminish tariffs and customs procedures.

This ambitious project, which entered into force in May 2019, is in its first phase of implementation, with negotiations underway to set the terms for trade in goods and services, and second-phase talks also in progress to address investment, intellectual property rights and competition policy, among other things. The third phase will include the digital economy and a special protocol on women and youth. As of the Tralac Law Centre’s May 2022 status update, no trade had yet taken place under the AfCFTA regime, but there is significant interest in supporting its successful implementation. [See above for a map and list of African countries that have ratified the AfCFTA agreement.]

While the goal of AfCFTA is to spur intra-African trade, it also sets the framework for foreign investors with the promise of a single trading bloc that is twice the size and population of the European Union. Today, as the continent sets the standards for its trade relations, it is working with China through a recently signed cooperation agreement to share experiences on intellectual property, digital trade, competition policy and customs procedures. Significantly, as the continent ascends to become the most dominant region on the globe, China is the country positioned to influence the policies Africa develops in the critical sectors for today and tomorrow.

If We’re Not Present, We’re Not Partners

Africa policy in the U.S. government and adjacent policy community has been for the most part an area of bipartisan collaboration, but the continent has not been seen as a strategic priority for Washington. This is markedly different from how allies and adversaries have viewed Africa. Countries as diverse as Turkey, Japan, Russia, South Korea, India and the United Kingdom have regular, ongoing summit-level talks with the African continent as a whole. Through the African Union, the continent has articulated a plan to achieve “the Africa we want”—the A.U.’s Agenda 2063 for sustainable development and inclusive growth—and African leaders are engaging with counterparts who are responding to the continent’s vision for the future.

Significant attention is given to China’s relationship with Africa, and this well-documented relationship has played a role in fueling China’s economic growth. Since 2000, China has held a triennial meeting with African counterparts—the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation—and has made no secret of its interest to create a closer connection with the continent. It’s little wonder that in 2009, China became the continent’s top trading partner and that in 2013 it surpassed the United States as the largest investor in Africa. During the 2021 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, Beijing signed a memorandum of understanding to provide technical assistance and support for implementation of the AfCFTA agreement, further extending its reach through standards setting in the chief vehicle that will dictate trade terms.

Similarly, in February 2022, Brussels hosted the sixth European Union–African Union Summit, in which the partners announced a new action plan through 2030 as part of their joint vision for renewed partnership. Using mutual interest as a guide and focusing on a joint program of shared priorities, the summit convened the 27 E.U. and 55 A.U. member states and signed onto a commitment to support projects in sectors ranging from health and energy to digital and infrastructure with €150 billion in investment. “As Africa sets sail on the future, the European Union wants to be Africa’s partner of choice,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stated Feb. 18.

The absence of high-level U.S. strategic engagement with the continent is striking. Our partnerships are on display nearly everywhere else in the world. In June, the United States hosted the ninth Summit of the Americas (SOTA), where the U.S. president has gathered with regional counterparts in the Western Hemisphere every three years since the U.S. convened the first summit in 1994 (and since 2012, this has included an accompanying CEO summit). The U.S. head of state meets peers annually in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum founded in 1989 that aligns the 21 countries of the Asia-Pacific with a goal of creating a more prosperous relationship through regional integration. (APEC’s Business Advisory Council, ABAC, is the model for SOTA’s CEO summit configuration.)

Significant attention is given to China’s relationship with Africa, and this well-documented relationship has played a role in fueling China’s economic growth.

Under the Transatlantic Declaration forged in 1990, the U.S. and the European Community have held regular dialogues and summits, and there is regularized coordination with Europe through the G7, OECD, NATO and various other multilateral fora that set the tone for the nations’ collaboration with the world.

The Biden administration appears to grasp that the United States would be wise not to miss a strategic opportunity that allies and adversaries alike have assessed and seized. In short, if we’re not present, we are not partners. As Secretary of State Antony Blinken explained in a May 19 interview with Stephen Colbert: “What we know is this: If the United States is not engaged, if we are not trying to lead … either someone else is—and that might not go forward in a way that reflects our interests and our values—or no one is, and that usually leaves a vacuum.”

Back to the Future

The Biden administration’s foreign policy focus on Africa has personal meaning for me as a former economic officer in the U.S. Foreign Service. Two tours in the Bureau of African Affairs launched a careerlong focus on Africa that I have carried beyond my tenure at State to my work at Carnegie Mellon University and now at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Though the Africa reset is certainly most welcome, for me, the calls for a more strategic policy focus on Africa engagement have felt a bit like Groundhog Day.

In 2005 I had the privilege of working on the annual African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) Forum dedicated to promoting trade and investment in Africa. Then 5 years old, AGOA was hailed as a success, with U.S. Trade Representative Rob Portman touting an increase in U.S. imports from sub-Saharan Africa of more than 50 percent and an increase in U.S. exports of 44 percent. The atmosphere was filled with optimism: The forum featured a special screening of the film “Africa: Open for Business” featuring success stories that showcased a vision of a modern continent filled with entrepreneurial drive, untapped opportunity and business success.

The ministerial-level event gathered officials, executives and civil society leaders under the theme of “Expanding and Diversifying Trade to Promote Growth and Competitiveness” one year after President George W. Bush had signed an extension of AGOA that included trade capacity provisions to support market utilization of tariff-free access to the United States.

AGOA has been described as the centerpiece of U.S. economic and commercial policy with Africa, and for two decades the forum has been the signature gathering between the U.S. and Africa. In recent years, the U.S.-African Union High-Level Dialogue, which extends beyond economic partnership to include other areas of cooperation, was added. While laudable and important, these gatherings are held at the ministerial level. But AGOA legislation was specifically designed to create an annual head-of-state engagement; the law requires the U.S. president to convene a forum annually on trade and investment relations and AGOA implementation between the United States and its African partners.

Which brings us back to the second U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, expected to take place in late 2022. The reality is that the United States has not accorded the continent the kind of sustained and ongoing high-level partnership dialogue and attention that it grants to other regions, even with legislative efforts designed to boost the same. But as the saying goes, the best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, and the second-best time is now.

This year, the United States can demonstrate a commitment to meaningful partnership with the nations of Africa through a summit that sets the tone and cadence for regular heads-of-state dialogue with our African partners on our shared priorities and opportunities. The president can make good on the commitment to reset relations and build back better by engaging the business community to play a significant role as part of a more holistic engagement of the continent, akin to other global summit dialogues.

Doing so can ensure that the United States is a partner today in the continent’s structural transformation under the A.U.’s Agenda 2063, and is positioned to be a partner in Africa’s emergence tomorrow.

Read More...

- “Africa needs more private funds for infrastructure investments - Africa50 CEO” by Ahmed Eljechtimi, Reuters, July 2022

- “Tackling Corruption in the Trading System through a Culture of Integrity” by Kendra Gaither, Global Trade Magazine, September 2020

- “Sierra Leone’s Dream: Diplomatic Activism, Not Dollars, Helped Bring Democratic Elections to a West African Country” by Charles Ray, The Foreign Service Journal, April 1998