Much Cause for Worry: A Clear-Eyed Look at Africa

It is time to put sentiment aside and look clearly at Africa through an objective lens, this Senior Foreign Service officer asserts.

BY MARK G. WENTLING

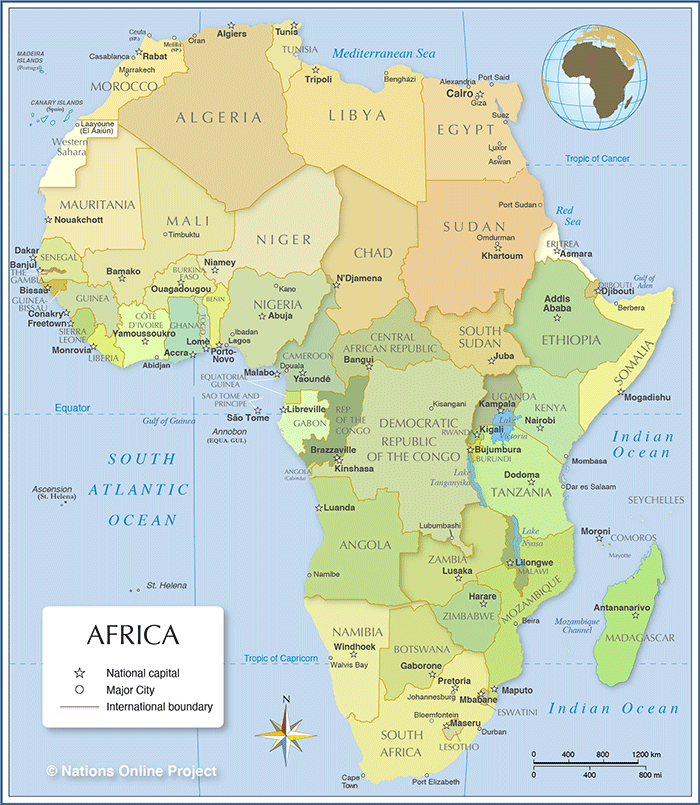

After working and living in every corner of the continent and visiting its 54 countries over the last 50 years, I cannot help but worry about Africa’s future, and I want to spell out why.

I apologize in advance to all my African friends. Though this article may come across as being too negative, I believe we need a dose of realism. It is time to put sentiments aside and look clearly at Africa through an objective lens, without exaggerating its future promise.

There is no question that peace, stability and good leadership are essential to the advancement of any country. Today the opposite exists in most African countries, limiting the continent’s future role in the world. Few have graduated from the lowest ranks of the poorest countries. All but three of the 31 countries listed in the lowest human development category of the United Nations Development Programme’s 2021 Human Development Index are in Africa. Despite many development efforts over the years, this has been the case since the annual HDI reports were initiated in 1990.

This is not to say that some progress has not been made. For example, the average adult literacy rate in Africa has increased from 49 percent to 66 percent from 1985 to 2019. And the infant mortality rate improved from 139 to 44 per 1,000 births in the 1970-2020 period. Importantly, during the past 50 years the status of women has also been elevated, in spite of Africa’s age-old patriarchal traditions. Indeed, women represent Africa’s greatest untapped resource. But while there has been progress in Africa, it has been much too slow.

I arrived in Africa for the first time in 1970, in Togo, a small West African coastal country that was known at the time as “the Switzerland of Africa.” There was a euphoric mood among the people. They believed that after 10 years of independence, real development was within grasp, and soon there would not be any need for external assistance.

Those were hopeful days in West Africa, where most countries gained independence around 1960. Little did the Togolese suspect then that the military coup perpetrated in 1963 would be the first of many in Africa, that they would have the same president for 38 years, and that upon his death in 2005, he would be replaced by his son, who still rules. My Togo experience has taught me many lessons about how difficult it is to achieve progress in an unpredictable Africa.

Yet Togo is a mild case of the kind of anti-development malaise that permeates most of the continent. Conditions are far worse in many other countries in Africa, which seem hell-bent on reversing the progress achieved over the last half-century. It is difficult to find an African country where competent and honest governance prevails and where justice is rendered to the people. Violent conflict exists in 20 African countries, and potential upsets in others cannot be ruled out. The violent activities of extremist groups are spreading. Living in Africa today obliges one to take many security measures.

Population Numbers. All African countries are coping with the tsunami of a fast-growing population. The youthful structure of that population (the average age in Africa is 19.7 years, compared to 38.5 years in the U.S.) presents formidable challenges. Rapid population growth is outstripping development gains. In 2050 Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, will have as many people as the United States in a land area that is one-eleventh the size of the U.S.

There are almost four times the number of people in Africa today than when I first arrived on the continent in 1970. Projections indicate that its total population will continue to expand, going from about 1.4 billion today to possibly more than 4 billion in 2100. I am at a loss to see how Africa can cope with this number of people.

The phenomenal growth of Africa’s population underscores the fact that it is the only region in the world which has not achieved a demographic transition—i.e., its birth rates remain high. Further, this growth in population is spawning rapid urbanization, which often translates into the growth of large informal settlements. The dire consequences of such unprecedented population growth, coupled with a massive rural exodus, on Africa’s development prospects are without historical parallel.

A Constrained Workforce. The fact that most of the world’s future workforce will be in Africa merits greater attention. While the working population in high-income countries is dwindling, the overall working population in Africa is increasing. Yet most adults in Africa remain jobless. If the litmus test of development is job creation, Africa can be judged a failure. A central question for wealthier countries with vacant jobs is how to engage Africans to fill these jobs.

A huge constraint on the use of the available labor force in Africa is the low educational and health status of the people. In most countries on the continent, a substantial percentage of the population is illiterate. And the prevalence of tropical illnesses such as malaria limits the contributions of its labor force.

Low scores in the education and health sectors are key determinants keeping most African countries mired in the bottom ranks of the HDI. Host governments and donors need to accept that these countries will always be in the lowest HDI ranks as long as these two key indicators—education and health—remain low. If the objective is to reduce poverty, improvements in these indicators are essential.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added to Africa’s burdens. On average, less than 10 percent of Africans are fully vaccinated, and there is a fear of new virus variants originating in Africa. The low percentage of Africans vaccinated represents a health threat to the entire world.

The fact that most of the world’s future workforce will be in Africa merits greater attention.

An Agricultural Paradox. Africa is also the only region in the world that has not had an agricultural productivity transition. Crop yields remain a fraction of what they are in other regions, and average farm size is small compared to other regions. The average age of the African farmer is increasing as young people abandon rural life for the towns and cities.

The absolute number of hungry Africans (in the millions) is rising. Food import costs for African countries are also rising. Yet Africa has the potential to not only feed itself but the rest of the world. In this regard, it represents something of a paradox. Currently, the shortage of food in Africa is being made worse by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Higher population densities oblige farmers to cultivate smaller acreage and marginal land. Part of the problem is a lack of access to the improved inputs needed to cultivate intensively. Farmers’ encroachment onto marginal lands has also added to large-scale deforestation and land degradation. Further, rampant illegal logging has resulted in the disappearance of millions of acres of Africa’s forests.

The lack of secure rights to land impedes any progress in dealing with Africa’s agricultural productivity failure. Only an estimated 10 percent of African farmers have legal title to their land. Africa remains the only region in the world where land ownership has not become fundamental to successful farming.

Coupled with this challenging agricultural production picture are negative nutritional factors, and these, too, hold Africa back. In many African countries, malnutrition among children is of crisis proportions. If good nutrition is the foundation of life, Africa has no solid foundation.

Challenges to Democracy. Further complicating the picture, ongoing civil conflicts have resulted in more than 20 million people fleeing their homes, either to become internally displaced or refugees in neighboring countries. With the rise in violent conflicts and unfavorable changes in the climate, this number is expected to grow. Added to this number are thousands of desperate migrants who try to escape poverty by making the perilous trek north to Europe.

There is much handwringing over the backsliding of democracy in Africa. Do not get me wrong. I am not for military coups that result in uncertainty or constitutional coups that maintain in power the same corrupt leaders, but I want what is best for the African people, particularly for future generations. Democracy works best in a low-income country when it is effective at reducing poverty.

I do not believe “good governance” requires the establishment of a widespread participatory democracy process modeled on wealthier countries. I also question whether a functioning democracy is possible in any low-income agrarian country with a high level of illiteracy.

Holding democratic elections is expensive, and the term “democracy” does not exist in most local African languages—but the word “justice” does. Most so-called Western-style democracies in Africa are a sham. Perhaps indigenous forms of participatory governance would be more appropriate.

Any decision on the form of governance to be adopted will need to consider a country’s multi-ethnic makeup and the colonial borders it inherited. National borders in Africa are those set by colonial powers in their scramble for Africa following the Berlin Conference in 1884-1885. When the African Union was founded in 1963, it accepted these borders.

Africans want justice. This could mean better schools, health clinics and water supplies. These services can be provided by a strong, benevolent leader who puts the best interests of the people and country first. My favorite kind of African leaders have no blood on their hands or large sums of money stashed away in foreign banks. Where in Africa do such national leaders exist?

The term “democracy” does not exist in most local African languages—but the word “justice” does.

PRC Involvement and the Debt Trap. Over the past 20 years, the People’s Republic of China has made inroads in Africa. China has tackled Africa’s large infrastructure deficit, providing expertise, funds and workers to construct ports, roads, railroads, dams and sports stadiums. The number of Chinese living and working in Africa has grown exponentially. Their willingness to live poor and work hard is unsurpassed.

Western countries have found they cannot compete with the Chinese. The Chinese do not express concerns over the environment, democracy or human rights as Western nations often do. The high amount of China’s loans to African countries has raised fears that it is causing a debt trap for Africa.

The national debt levels of a number of African countries are, indeed, rising, and it is expected they will be obliged to default on their debts. Economic dependence on the export of one or two commodities is not a solution to Africa’s financial problems.

More money leaves Africa illicitly than goes into it through legitimate channels. Until this kind of corrupt financial hemorrhaging is cured, can there be any hope for a better future for Africa?

Money and Minerals. The continent has natural resources the world needs. It is regrettable that a number of African countries are exploiting a wealth of natural resources, but their people remain poor. There are too many countries in Africa where the country is rich and people are poor. This is a contradiction that only Africans can resolve.

One example of this contradiction is the strife-ridden Democratic Republic of the Congo. This country is larger than Western Europe. The DRC is gorged with natural resources. Yet its people are among the poorest in the world, while its deeply corrupted elites are fabulously rich. It also has a dense forest cover that plays a critical role (after the Amazon Basin) in absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

No doubt the DRC possesses resources the world needs, but if the international community does not act, these resources will be squandered. These resources include rare minerals like cobalt and coltan, necessary for the manufacture of electric cars and mobile phones. These minerals are largely mined in a chaotic fashion by criminal gangs.

Since the survival of the planet may be at stake, it is past time for the international community to take seriously what is happening in the DRC. Firm arrangements for efficiently and honestly managing the mining of these minerals and the DRC’s tropical forest must be concluded between the DRC and the international community.

Increasingly, illegal activities that did not exist before are now major preoccupations. The trafficking of humans, arms, drugs, gold, diamonds, animals, timber, money laundering and counterfeit medicines is now commonplace. International organized crime is well implanted in Africa, and criminal cartels control lucrative businesses.

The world is changing quickly. Africa must run fast to stay in the same place. Climate change makes it even more difficult to advance. Where does the hope for the future of Africa lie?

It seems few Americans care about Africa. I care, but I am helpless to change the course of history. I can see that if the negative trends of this large and diverse continent of more than 2,000 ethnic groups are not reversed, there is much cause for worry.

Read More...

- “The Global Slowdown: Why Sub-Saharan Africa is so Important” by Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou and Naomi Aladekoba, The Atlantic Council, August 2022

- “Slaughter South of the Sahara: No Scope for ‘Business as Usual’” by Mark Wentling, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2020

- “Born in Kansas, Made in Africa” by Mark Wentling, The Foreign Service Journal, January 2012