Helping Refugees in Poland

One FS family member shares her “all-consuming” experience on temporary duty in Warsaw during the war in Ukraine.

BY LILIA LALLY

Located at the Przemysl train station, the World Central Kitchen has been serving meals every day since the war in Ukraine began.

Courtesy of Lilia Lally

Poland was receiving thousands of refugees fleeing Ukraine, and the U.S. Embassy Warsaw requested volunteers to assist with demand. On Monday, March 14, I received confirmation from the Bureau of Consular Affairs that my nomination as a volunteer to assist U.S. Embassy Warsaw with Mission Poland had been approved. Because I was born in Ukraine, participating in this temporary duty (TDY) assignment was my dream from the moment the war began on Feb. 24, 2022. I arrived in Warsaw on Wednesday, March 16, and immediately started interpreting from Russian and Ukrainian into English for consular officers and locally employed staff on the visa line.

There, I met a dedicated consular team whose members had come to serve on TDY assignment from around the world: England, South Africa, Taiwan and South Korea, among other places. I was also glad to reconnect with colleagues from Embassy Kyiv’s consular section, where I had worked from 2018 to 2019. They contributed their unique knowledge of Ukrainian naming conventions and other invaluable local knowledge that helped inform visa decisions. I was so grateful for my Polish consular colleagues, as well, who welcomed us and whose graciousness provided us the comfort needed to do this difficult work. Our team of approximately 60 people all worked together to support this effort.

On the visa line, the team adjudicated hundreds of cases each day. This was not easy. Consular work relies on a strong knowledge of U.S. immigration law, but adjudications also draw heavily on local cultural knowledge and experience. Not only was our group of TDYers new to this applicant pool, but the Ukrainian applicant pool had been fundamentally changed by the war, as well. Most of them had never applied for tourist visas before, and all of them had just left a life that had been completely upended. The primary applicants were mothers with small children accompanied by grandparents or relatives.

Because I was born in Ukraine, participating in this temporary duty (TDY) assignment was my dream from the moment the war began on Feb. 24, 2022.

Most of their stories were the same. They were traveling to visit a cousin or other relative and planning to return to Ukraine as soon as the war is over. They were planning to stay only for a few months since their husbands, sons, brothers and fathers were left behind. One young boy was so excited to receive a visa that he started crying when told it was approved. His mother explained that he had just spent days in a bomb shelter. A family of five had to stay in a school’s gym while waiting for the interview. They were so delighted to continue their journey after their visas were approved.

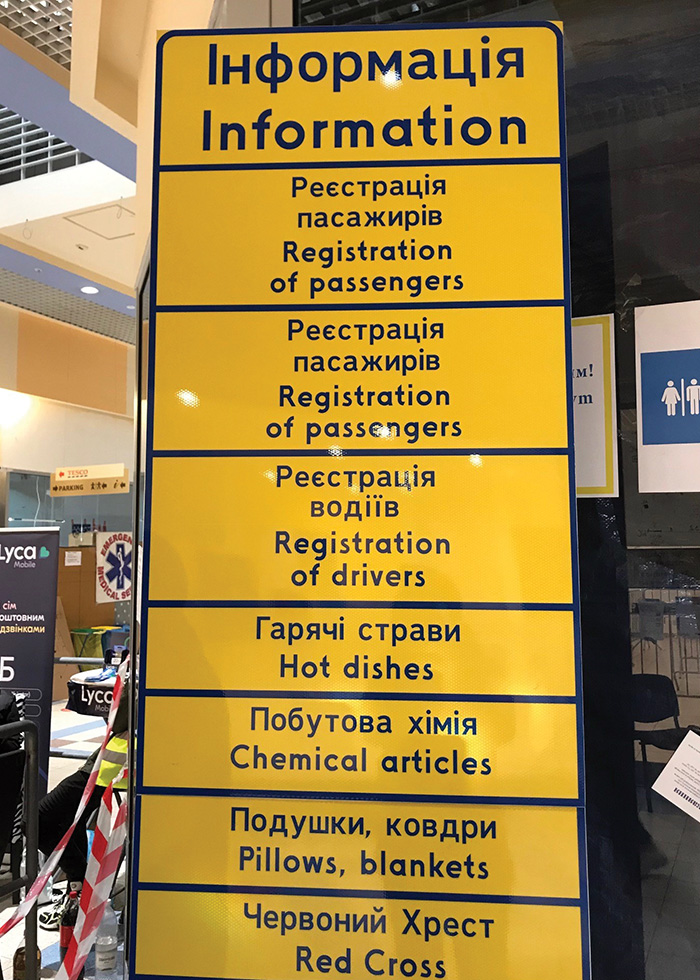

The Registration Center in Przemysl, Poland.

Courtesy of Lilia Lally

Courtesy of Lilia Lally

It was not only Ukrainians who were applying for visas; Russians were, too. The officer’s job is to assess each application individually, taking into consideration all the factors unique to each applicant. With U.S. Embassy Moscow’s staffing severely decreased due to Russian government strictures, Russians have been applying for visas across the world. Many of the Russian applicants we saw in Poland had traveled to the United States previously and were simply looking to do the things people, regular people, do. They were visiting friends and family. They have children in American universities. We provided the same service to them as to Ukrainian applicants and the same careful consideration of each specific case as we do for people everywhere.

But this was just one facet of a huge, all-of-government international response. For example, the U.S. Foreign Commercial Service office in Warsaw had begun assisting Ukrainian refugees almost immediately after the invasion started. They received large volumes of inquiries from U.S. companies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) looking to provide support, and they got to work connecting donors with needy recipients.

Because of their unique relationship with the private sector, FCS could easily route offers of assistance, help donors navigate Polish customs clearance, identify freight forwarders that could manage cross-border shipments, and work with the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs to help ease bureaucratic bottlenecks. FCS started tracking acts of corporate social responsibility and worked closely with the embassy’s public affairs section to amplify the support U.S. companies provided to Ukraine relief efforts through the embassy’s social media channels.

It was not only Ukrainians who were applying for visas; Russians were, too. The officer’s job is to assess each application individually, taking into consideration all the factors unique to each applicant.

Shortly after arriving, I joined my colleagues at Mission Poland’s American Citizens Welcome Center in the southeastern border town of Przemysl. The center was open 24/7 for more than six weeks, and more than 1,900 Americans received assistance from consular staff by phone or face-to-face. Working side by side with the Warsaw and Krakow American Citizens Services teams, we were able to assist families with emergency passports, transportation and lodging, and general information.

Lilia Lally (right) volunteering at the World Central Kitchen in Przemysl, Poland, with Holly Connor (left), a volunteer from EngenderHealth, an NGO in Washington, D.C.

Courtesy of Lilia Lally

The author in front of U.S. Embassy Warsaw in March.

Courtesy of Lilia Lally

I remember one instance meeting a mother and children who, after just crossing the Ukrainian-Polish border on foot, carrying a saxophone, guitar and ice skates, were finally able to find some rest in a local hotel, thanks to U.S. government support, while we helped prepare and provide them with new U.S. passports and loan applications. Thanks to our support, the family was able to fly to the United States where these small children could find at least some sense of stability, continuing their education in a U.S. school.

In another instance, this one rather surreal, the center facilitated bringing infants born to Ukrainian surrogate mothers across the Polish border into the waiting arms of their new American families. With the help of the Regional Security Office, these newborn children were carried first by Ukrainian ambulances and then Polish fire trucks. None of this could have happened without the support of Polish authorities and many volunteers.

Between shifts, I was able to volunteer at the World Central Kitchen in Przemysl. Since the beginning of the war, World Central Kitchen founder José Andrés and WCK’s volunteers had been serving meals every day around the clock—more than 300,000 by the time I arrived. Many Ukrainians were able to receive hot meals with sandwiches at the train station in Przemysl. The food was delicious, nutritious and novel. Many Ukrainians probably tasted a chicken sandwich and Austrian apple strudel for the first time in their lives. I was impressed how well the facility was set up: volunteers from the United States, Spain, Switzerland, Poland and elsewhere kept the place spotless and up to the highest hygiene standards.

My experience was all-consuming. My whole world for this period was the war, the crisis and the people directly affected by it. On returning home to Brussels, I joined my family in welcoming four Ukrainian refugees there.

Read More...

- “In Poland, refugees from Ukraine escape the danger, but not the war” by Lydia Tomkiw, The Christian Science Monitor, May 2022

- “Reflections on Russia, Ukraine and the U.S. in the Post-Soviet World” by Michael Tefft, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2020

- “Oral History in Real Time: The Maidan Revolution” by Joseph Rozenshtein, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2017