From Guitars to Gold: The Fruits of Economic Diplomacy

This selection of first-person accounts showcases the work members of the Foreign Service do around the world every day to promote U.S. business.

Bob Taylor works with an employee in Cameroon to fine-tune the settings for cutting ebony.

Photo Courtesy of Bob Taylor

Often the best diplomatic work leaves no trace because it is achieved behind the scenes, through partnership and shared effort—and an insistence on giving all credit to others. Which is why, when we began planning this special issue six months ago, we put out a call to active-duty and retired members of the Foreign Service, soliciting their best stories about practicing economic diplomacy—“from the smallest success no one outside post would ever hear about, to the biggest, headline-grabbing accomplishment.”

This collection, selected from the many submissions we received, illustrates the critical, everyday work of the U.S. Foreign Service around the world on behalf of the United States in the realm of economic and commercial diplomacy.

Our thanks to all who shared their experiences.

—The Editors

Ebony for Taylor Guitars

CAMEROON, 2015 • BY MICHAEL S. HOZA

Bob Taylor, foreground, works with colleagues in Cameroon on the equipment he brought into the country.

Photo Courtesy of Bob Taylor

In 2015 Cameroon was an island of relative stability in a very troubled subregion, hosting half a million refugees from conflicts in neighboring states. It was besieged by many of the ills afflicting its neighbors: piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, Boko Haram’s violent extremism in the Lake Chad Basin, waves of infectious disease threatening its population and rapacious neocolonial trade practices by many Chinese companies.

The U.S. government had gained a measure of access and influence with the government of Cameroon through our partnerships to fight piracy, violent extremism and health pandemics. We found dedicated Cameroonian professionals who used our training and equipment to drive piracy out of Cameroonian waters, drive Boko Haram back into Nigeria, eradicate polio and stop outbreaks of bird flu virus and Ebola. The United States was increasingly seen as a reliable partner, and we used that credibility to open the door for American companies hoping to do business in Cameroon, a country that was widely disparaged for its unwelcoming business environment.

Chinese business practices in Cameroon had been ruinous for the country. First, Chinese companies did not create jobs for Cameroonians. They imported their own labor from China, and often left the laborers stranded in Cameroon after the project was completed. Second, China extracted raw materials, but never transferred technology to enable Cameroonians to develop value-added manufacturing. Third, Chinese companies were directly responsible for an overwhelming rate of corruption that was choking the socioeconomic environment. And, finally, Chinese companies did not engage in any form of corporate social responsibility. For more and more Cameroonians, it was increasingly evident that the bloom was off the Chinese investment rose.

Our embassy approached the government of Cameroon with an alternative—American companies and investors. We promoted U.S. companies based on “four points”: they would create jobs for Cameroonians; they would transfer technology to Cameroon; they would adhere to the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and maintain transparent accounting; and they would engage in corporate social responsibility for the betterment of the Cameroonian people, flora and fauna.

One of our greatest success stories was Taylor Guitars, one of the leading manufacturers of acoustic guitars in America.

As a young man many years ago, Bob Taylor went into his father’s garage and made his first guitar. By 2015 he was selling well over 140,000 guitars a year in the United States alone, and he got all of the ebony that he needed for his guitars from the trees of Cameroon.

Bob Taylor’s vision for ebony production from Cameroon dovetailed with our embassy’s “four points” policy for commercial advocacy. He began by assuming ownership (with Spanish partner Madinter) of the ebony mill, Crelicam. In addition to the 75 Cameroonians directly on Crelicam’s payroll, he worked with banks to establish transparent payment mechanisms for thousands of individual Cameroonian suppliers. Bob walked the talk of creating jobs for Cameroonians—and the jobs he created were good jobs. He brought in state-of-the-art machinery to process the ebony to the exacting specifications demanded by his guitar factory, and trained Crelicam employees to operate and maintain the machines. Bob was often in Cameroon, not in a suit and tie, but in overalls, working alongside his Cameroonian partners.

As much as he enjoyed seeing the Crelicam operation grow in expertise and productivity, Bob was not doing this out of pure altruism. Shipping fine finished pieces of ebony to his guitar factory in the States was a lot less expensive than shipping whole ebony logs. And apart from lowering his production costs, Cameroonians with good jobs represented the beginnings of a middle class that would eventually become consumers of his product.

During one visit Bob was surprised when he entered the office of the local tax assessor, who made it clear that a large bribe was all it would take to give Crelicam and Taylor Guitars a clean tax audit for the year. He walked out of that tax office and straight into my office at the embassy to tell me what had happened.

Thanks to a close working relationship, the embassy soon had an audience with the minister of finance, a young, Western-trained, progressive and highly respected technocrat. By the time the meeting was over, Bob Taylor was promised a fair audit and was notified of his eligibility for a tax holiday for foreign investors who create Cameroonian jobs. While it is unfortunate that we had to go all the way to the ministerial level to get a just outcome, we were grateful for the opportunity to bring Crelicam to the minister’s attention. It was our way of building a healthy business “microclimate” around an American company in what was otherwise acknowledged to be a difficult business environment.

When it came to corporate social responsibility, Bob Taylor proved to be one of the finest examples of American entrepreneurship. He won the Secretary of State’s Award for Corporate Excellence for his responsible harvesting of ebony, but he was not content to stop there. He forged a partnership with the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Congo Basin Institute in Yaoundé to grow ebony seedlings, and developed a mechanism to make it worthwhile for small farmers to tend the seedlings until they could grow on their own. Investing more than half a million dollars of his own money, he got the program off the ground in Cameroon—and can now say that he is planting more ebony than he cuts down. We were so proud of his initiative that we planted two of his seedlings on the embassy compound and one at the ambassador’s residence, amplifying the program through a public diplomacy campaign.

In Cameroon the reaction to the Taylor Guitars initiative was instructive. Pro-American sentiment went up wherever the Crelicam story was told. French commercial logging companies came to us to ask how they could start similar reforestation programs. And the Chinese ambassador thanked me, as the example of Taylor Guitars helped him discipline some of the more wayward companies from his country.

The Minister of Environment of Cameroon signed a private-public partnership agreement with the company at the United Nations Climate Change Conference held in Bonn in 2017 to partner in ebony propagation under the direction of Taylor Guitars and the Congo Basin Institute. And the Cameroonian government sent a trade delegation to the United States to find more American companies like Taylor Guitars.

The Taylor Guitars model served as the kernel around which we built our broader commercial engagement. The reputation for transparency we developed, as well as the new channels of communication we pioneered within the Cameroonian government and the private sector, created openings for other U.S. companies to successfully bid on and receive contracts and other opportunities.

Protecting Intellectual Property Rights

ITALY, 1990S • BY KEVIN MCGUIRE

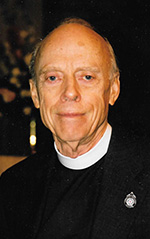

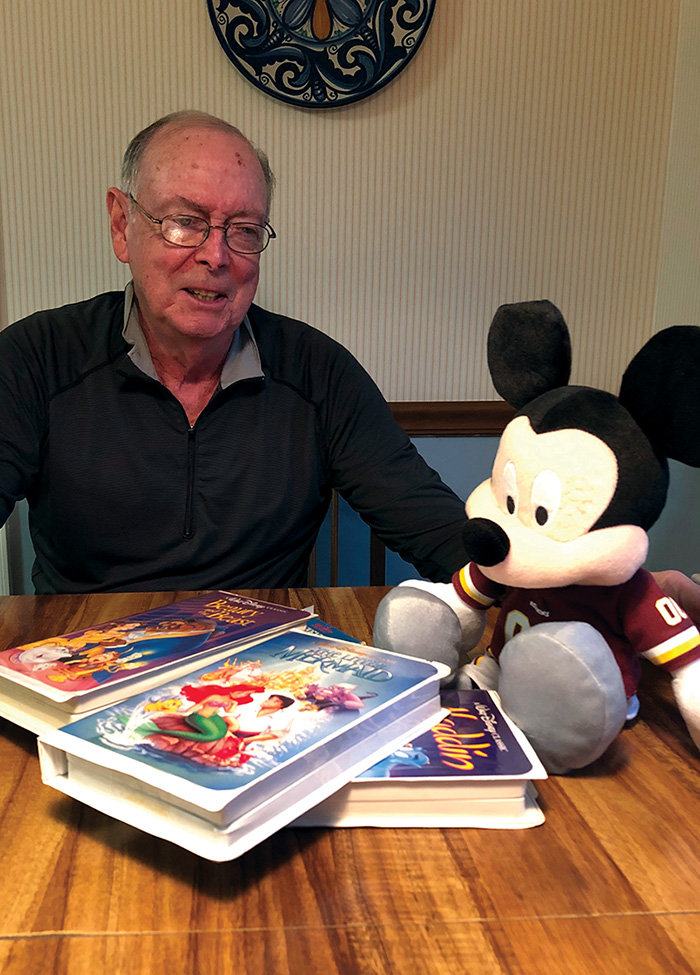

Mickey Mouse and Kevin McGuire reminisce about past battles.

Courtesy of Kevin McGuire

There is a great deal of attention today on problems with intellectual property rights (IPR) violations, particularly by China. This is not a new issue, and it is worth noting that a great deal of progress has been made in this area over the years through persistent bilateral and multilateral diplomatic efforts. In the late 1980s, we at Embassy Seoul spent a great deal of time and effort on such issues, with significant success. But as I discovered after being transferred to Rome as economic minister counselor in 1990, IPR problems are not always restricted to developing nations.

The U.S. Business Software Alliance informed us that they planned to seek U.S. trade retaliation against Italy because of the tremendous amount of pirated software that was being sold and used there. We suggested that perhaps a better way would be to work with us at the embassy to put together a program to address the problem. The BSA was enthusiastic about trying that approach; and so, working closely with their representatives, we organized an all-out blitz.

We approached Italian companies involved in software/hardware-related products and found they shared our concerns. Italian businesspeople were very eager to participate in developing a program that would put new laws in place and enforce them. We went to the foreign ministry and the prime minister’s office, and we talked to political party representatives. We got the BSA and their Italian colleagues to come up with specific draft legislation that would help solve the problem and also asked for suggestions on how enforcement could be improved.

With cooperation from Italian ministry officials, we sold the package to the parties in the coalition government, and the legislation passed. New enforcement techniques were also put in place to help police the new regulations. I remember getting phone calls from Italian contacts saying, “You’re a real pain in the neck. I’ve got the Carabinieri in my office looking for pirated software.” The effort was so successful that instead of pushing for a special Section 301 action against the Italians, the BSA got a resolution passed in the U.S. Congress praising the Italian government for its efforts in dealing with the piracy problem.

The case was an interesting example of how an embassy can be an activist in conceiving programs and putting together coalitions to help solve serious problems for American companies. We were successful because we had sufficient staff in the economic section, a staff that was well-trained and capable of maintaining strong ties to relevant host-country officials and to the local business community.

Disney representatives, who had previously avoided coming around to see us, heard about our success. They had earlier decided to address their film piracy problems through the courts, but that approach was proving expensive, time-consuming and largely fruitless. After our partnership with BSA produced results, Disney asked us for help, as well. So we sat down with a Disney team and plotted out a somewhat different strategy for dealing with their problem.

We used many of the same players in the Italian government, starting with the foreign ministry and the prime minister’s office, and also the parliament and law enforcement agencies. We got Disney and other moviemakers who had been affected by piracy to sponsor seminars for judges and supervisory police officials to educate them on the nature of the problem and ways to get rid of it. Once again, we found strong Italian support for action, in part because proceeds from many of the pirated videos were going to organized crime, the Mafia and its equivalent in other parts of the country.

Before we got involved, things happened along the following lines. A film courier would come into the country carrying a sealed bag with copies of a first-run movie. The movie was supposed to be delivered to the relevant theaters the next day, but the Mafia would pay off the couriers. They had warehouses set up with hundreds of recording machines, so they could make thousands of top-quality copies overnight and have vendors out on the street selling them before the film was released. As a result of our efforts laws were strengthened, and the police put additional people on the monitoring side, closing down illegal copying facilities and arresting street vendors. Judges began handing down heavy punishments for violations. It was another example of what an adequately staffed embassy can do when confronted with a problem.

Very few Americans know about these types of diplomatic accomplishments. The BSA people were very gracious, both privately and publicly, in their praise of the embassy, including with the U.S. Congress; but, unfortunately, that is atypical. However, I greatly valued the Mickey Mouse T-shirt my staff gave me for my birthday as a reminder of our excellent antipiracy work.

The Asian Financial Crisis: The Ground View from Jakarta

INDONESIA, 1997 • BY BRIAN MCFEETERS

The 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis began, most observers later agreed, on July 2, 1997, when the Thai government allowed the baht to float against the U.S. dollar, throwing a wrench into the region after an amazing decade of growth. The same day, my family and I arrived in Jakarta, and I began my third FS assignment, as finance and development officer at U.S. Embassy Jakarta.

Coming directly out of the Foreign Service Institute’s nine-month economic training, I would love to be able to say that I saw the financial storm on Indonesia’s horizon and alerted Washington about it. Instead, as I began to meet government officials and foreign bank executives, I believed what they told me: the fundamentals were sound. Indonesia was not like the other overextended Asian economies. It boasted world-class macroeconomic management, a solid foreign investment inflow, rich natural resources and an emerging middle class. Though sitting atop a corrupt system for decades, President Suharto had kept things stable and economic deals flowing. Even when Indonesia followed other regional countries and floated the rupiah in August, Jakarta’s in-the-know circle stayed calm.

In October 1997 Ambassador J. Stapleton Roy, an inspiring leader, summoned our economic section to his office. He told us he didn’t want the embassy to keep telling Washington that the fundamentals were sound and have the Indonesian economy “come crashing down around our ears.” Economic Counselor Judith Fergin and her deputy, Pat Haslach, told us to dig deeper. Judith, working her huge network of contacts, began daily phone briefings back to State and Treasury. Banking contacts I had met a few months earlier now sounded worried. They said funds from abroad—which Indonesian firms relied on to keep rolling over short-term U.S. dollar loans—were drying up.

As things grew more uncertain, FSI economic course cochairman Barry Blenner was my lifeline. I often called him at night, taking advantage of the 12-hour difference, to talk through the worsening situation and prepare for the next day. For example, I once confidently briefed the ambassador and country team about the need for the government to sterilize the money supply, keeping the overall supply stable as foreign assets were increasingly withdrawn, based on Barry’s explanation the night before.

By January 1998 there were no more illusions about Indonesia. The exchange rate, our main instability indicator, suddenly weakened to 12,000Rp/USD compared to just 2,400 in August. The crisis hit the real economy. Half-built skyscrapers in central Jakarta became deserted sites, and businesses shut down. Real GDP would decline by 13 percent that year. Ambassador Roy called us in again, saying that a senior Treasury official wanted his bottom-line assessment on where Indonesia was heading. He gave us until close of business.

Pat Haslach, running the section that day, gathered us in the common area and asked us each to write a short summary of the situation and our recommendations. A mid-level officer, I felt empowered, recognizing that other senior officers might have taken sole lead on such a high-priority project. We jointly described the situation as dire and government credibility as low. We suggested that a senior U.S. government official come meet with President Suharto to recommend that his government seek International Monetary Fund assistance. A few days later, Secretary of the Treasury Larry Summers came, and Suharto reluctantly agreed to negotiate with the IMF.

Had the problems been solely economic in nature, the IMF intervention package agreed to in April may have righted the ship. But by then the crisis was political, too; and we worked with political section colleagues to convey the emerging reality to Washington. A front-page newspaper photo of IMF Chief Michel Camdessus standing over Suharto with his arms crossed signaled to many status-conscious Indonesians that their president had knuckled under. I called financial-sector contacts to ask questions about the economy, and they answered by saying that Suharto needed to go.

In early May 1998 riots that, in retrospect, appear to have been staged broke out across the Jakarta metro area and elsewhere in Indonesia. That was the beginning of the end. In late May, Suharto stepped down, resigning after his Cabinet and key military leaders abandoned him.

By then, my family and I had been evacuated back to Washington, out of concern about mounting street violence and an expected million-person march in front of the presidential palace near the embassy. We relied on management section colleagues to put us on chartered flights out of the panicky city. The crisis that began as a financial phenomenon developed into a political and security crisis that the whole mission needed to cope with.

In July 1998 my family and I returned to a different Indonesia. The worst of the financial crisis was over, as the controversial but effective IMF stabilization policies took effect. But Indonesia was knocked down and sobered, taking the better part of a decade to get back to 1997 economic levels.

Social Entrepreneurship Takes Center Stage

TOGO, 2017 • BY DAVID GILMOUR

Ambassador David Gilmour visits the Olympia, Washington, headquarters of Alaffia, guided by CEO Olowo-n’djo Tchala and company staff.

Courtesy of Alaffia

Ambassador David Gilmour (center), Alaffia CEO Olowo-n’djo Tchala (third from right) and a delegation of senior Whole Foods Market officials dedicate a partnership-financed primary school in rural northern Togo.

Courtesy of Alaffia

In sub-Saharan Africa, U.S. embassies strengthen commercial ties and promote economic growth to achieve our national security goal of making African countries stable and reliable partners for the United States. That task is especially challenging in Francophone Africa, where the language barrier and obstacles in the operating environment can discourage American companies from investing.

In Togo, our embassy tackled the problem by creating partnerships with private-sector companies, civil society and the host government to promote education, environmental protection and public health, while working to improve the business climate and encourage trade with the United States.

A small post like Lomé with a limited foreign aid budget might seem to have little to offer partners, but we crafted a unique approach to attract them. When Togo was selected for a Millennium Challenge Corporation Threshold program, a team of American and Togolese economists set out to identify the binding constraints in its economy. The embassy seized the opportunity of that MCC research project to significantly ramp up our contacts within the business community.

We launched a series of dialogues with businesspeople to learn about their challenges and listen to their ideas for improving Togo’s investment climate. I stressed the need to improve the business environment in nearly every speech I gave, and we strongly promoted entrepreneurship programs. We initiated a public-private working group to promote English-language teaching, stressing the economic opportunities for young people and the benefits to a business community in search of talent.

Our team established a “U.S.-Togo Business Forum” of American-associated businesses and promoted the services of regional resources like the USAID West Africa Trade and Investment Hub and the Foreign Commercial Service. We also supported the government of Togo in hosting the 2017 African Growth and Opportunity Act Forum, which brought together 39 AGOA-eligible African nations and the United States for this annual dialogue to foster increased U.S.-Africa trade and investment.

Using MCC and other activities like the AGOA Forum, we branded the embassy as the most prominent advocate for improving Togo’s business climate. The private sector saw value in our activities and perceived us as an ally, and our enhanced convening authority brought numerous partners to the table.

With that support, we collaborated on projects that offered businesses the opportunity to demonstrate good corporate citizenship, while enriching Togo’s human capital. To support educational advancement, local companies joined us to sponsor a national English-language competition in which more than 10,000 Togolese high school students from more than 600 schools participated. Students gained valuable skills, and businesses could recruit talented scholars when they graduated. The embassy collaborated with U.S. company Contour Global to outfit a donated bus with computer equipment and scientific gear, creating a mobile learning lab that visited schools to offer hands-on experience with science, technology, engineering and math.

We also teamed up with American companies, U.S. alumni of exchange programs and the Togolese government to create a nonprofit organization to promote environmental education and carry out community cleanup activities, which regularly drew several hundred volunteers.

In health care, we enlisted an American company to pay the shipping costs of donated medical equipment from the United States to outfit hospitals in Togo’s underdeveloped rural areas. We also leveraged U.S. Defense Department funding to attract an American company to help renovate and equip a health clinic in a populous Lomé neighborhood.

Our most fruitful partnership was with the Olympia, Washington-based company Alaffia, which makes natural skin and hair care products from African ingredients like shea butter and coconut oil. Founded by a returned Peace Corps Volunteer and her Togolese husband, Alaffia operates on a fair trade and social entrepreneurship model that emphasizes doing good works while generating jobs and making profits.

This “conscious capitalism” approach is rapidly gaining popularity in the United States, where American consumers increasingly demand products that are responsibly sourced and environmentally sustainable. For African countries with agriculture-based economies, fair trade and social entrepreneurship represent exciting new opportunities to supply natural and organic products, and to increase economic prosperity for their citizens.

Inspired by Alaffia’s success, Embassy Lomé made social entrepreneurship a centerpiece of our trade promotion activities. I visited the company’s Washington state headquarters to highlight both the creation of American jobs and the social impact in Africa. We organized a campaign to educate the Togolese about social entrepreneurship and opportunities in the fast-growing $200 billion American market for natural, organic and fair-trade products.

We showcased American and Togolese social enterprises at the embassy’s Independence Day celebration and organized a major conference on social entrepreneurship. Following that conference, the Togolese government established a special public-private task force to promote social enterprises and recommend policy changes to facilitate their formation.

After we highlighted social entrepreneurship and fair trade at the AGOA Forum in Lomé, organic supermarket giant Whole Foods Market sent a delegation to Togo to deepen its supply chain connections with West Africa. The government of Togo is considering a “fair-trade friendly” marketing campaign for the country.

Embassy Lomé’s business partnerships produced winning results for everyone involved. We helped American companies showcase their corporate citizenship while enhancing the business climate and demonstrated the tangible ways that diplomats assist U.S. businesses overseas. By promoting social entrepreneurship and fair trade, we enhanced America’s image, communicating that U.S. consumers are responsible global citizens who care about the welfare of producers in developing countries.

We showed that fair trade raises rural incomes and reduces dependence on foreign aid by helping producers tap rapidly growing new markets. We helped change the Togolese mindset about the role of government, and proved that citizens can work with businesses to make positive changes in their community. Our embassy partnerships were a multiplier that vastly stretched our limited resources, inspired our staff members and improved morale.

The Secretary of State’s Office of Global Partnerships recognized our efforts with its annual Partnership Excellence Award and cited Lomé as an “Embassy to Watch” in its 2018 annual report. Alaffia was the recipient of the 2018 Secretary of State’s Award for Corporate Excellence for Women’s Economic Empowerment.

Beer Diplomacy: Craft Brewing and U.S. Agricultural Export Promotion

BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO, 2018 • BY PREETI SHAH

Founding members of the U.S.-Mexico women’s brewing nonprofit “Dos Californias Brewsters” at the Ensenada BeerFest last March.

U.S. Consulate Tijuana / Jose Maria Noriega

Consulate General Tijuana applied an array of business promotion and public diplomacy tools to the growing craft beer industry in Baja California over four months last year to further three U.S. Mission Mexico goals: expansion of U.S. exports and business; development of local entrepreneurship, small businesses and the workforce; and promotion of gender equality. Working with our interagency partners from the Foreign Agricultural Service and the Foreign Commercial Service, we developed a multipronged program that pulled together experts and participants from each stage of beer brewing, including marketing and export, to promote U.S. economic growth while simultaneously supporting young, mostly female entrepreneurs in Mexico.

Mexico’s craft brewing industry is rapidly expanding, and Baja California has the highest concentration of craft breweries in the country. U.S.-grown barley and hops and U.S.-manufactured brewing equipment are key to their success. Through sustained engagement with the brewing industry, we solidified the U.S. role as a key economic driver in the binational border region, and ensured U.S.-grown agricultural exports would be the preferred base ingredients to brewing craft beer in Mexico.

We also tapped into the Cicerone certification program, a U.S. business-sponsored initiative that educates and certifies beer servers, brewers and critics, much like the process a sommelier goes through to become a certified wine expert. Cicerone representatives were eager to gain a foothold in the Mexican market, and we connected them with representatives of the brewers’ guild, Tijuana and Ensenada restaurant associations, universities and large breweries.

As a result, Cicerone developed more than 10 new potential contracts in Baja California and a host of new contacts with whom to explore further business relationships. In addition, numerous Southern California and Baja California breweries have partnered to brew and distribute beer on both sides of the border, increasing their visibility and economic success in both consumer markets.

Women are underrepresented in the Mexican craft brewing industry. As part of the consulate’s support to the Ensenada Beer Congress, we brought together female representatives from the agriculture, marketing, brewing, industry advocacy and certification parts of the industry.

In one of the best-attended sessions of a three-day conference in Ensenada in March 2018, we hosted a panel, “Women in Brewing,” in which five women from both countries discussed inclusion, diversity and gender equality in the field of craft beer. Connecting female brewers from Southern California with Baja California female brewers facilitated business and mentoring relationships. One immediate result was that Baja California women established the first Mexican chapter of the Pink Boots Society, a beer industry nonprofit designed to build mentorship opportunities for women in brewing.

This cross-border group also went a few steps further and brewed unique beers for the Ensenada BeerFest, using the profits from their sales to endow scholarships for young female brewers to get their brewing science certificates at Baja California universities. The group’s binational board also established itself as a nonprofit in Mexico and plans to continue brewing together with the goal of supporting young female brewers.

Craft brewing was an ideal vehicle—especially in the border region that embraces U.S. trends and interests before the rest of Mexico—to showcase the benefits of export and business promotion, as well as to highlight U.S. commitment to entrepreneurship, gender equality and workforce development. (And we got to sample some terrific products along the way.)

Open Skies, Open Markets

BRAZIL, 2018 • BY PAUL BROWN AND NAOMI C. FELLOWS

In 2011 the United States and Brazil signed a bilateral Open Skies Air Transport Agreement to provide new market access options for the airlines of both countries. Open Skies agreements give the public expanded choices for flights and services and offer exporters more choices when they ship goods. These benefits would only become available once the agreement entered into force—but for that to happen, Brazil’s National Congress needed to ratify the agreement. From 2011 to 2016, however, the agreement remained with the Brazilian executive branch and legislature. In the meantime, air links between the two countries were limited, affecting both market entry and services.

Delay in reaching a new agreement imposed real costs on both countries. The United States is the biggest market for international flights with Brazil: U.S. air carriers transport more than 60 percent of the passengers between the two countries. But they could not reap the full benefits of their investment in Brazil or with Brazilian airlines without Open Skies in place. Alliances and proposed joint ventures between U.S. and Brazilian airlines—the norm in the liberalized aviation markets of several other important Latin American partners—also remained at a standstill pending entry into force of the new agreement.

With the arrival in office of a new Brazilian president in 2016, U.S. Embassy Brasilia, working closely with the State Department and interagency colleagues, undertook a concerted campaign to put ratification of the agreement at the top of our bilateral economic agenda. The ambassador and country team members repeatedly raised the issue with Brazilian officials and legislators. The embassy facilitated a visit by Brazilian congressional leaders to Washington, D.C., where U.S. officials were able to stress the benefits of ratification. Senior State Department officials raised the issue with their Brazilian counterparts to make clear the importance we placed on this agreement in the context of the overall bilateral relationship.

The team spent days on the floor of the Brazilian Congress tracking how members were voting and engaging congressional staff when the vote became close.

Embassy officers and Locally Employed staff intensively engaged Brazilian legislators and industry representatives. Over a five-month period, from October 2017 through February 2018, we strategized and executed a missionwide, vote-by-vote advocacy effort in Brazil’s Congress. We made the case for Open Skies with the Brazilian travel, tourism and business groups who would benefit from the agreement, encouraging them to advocate with their congressional representatives in favor of Open Skies ratification.

The embassy’s insight into the Brazilian Congress and its internal dynamics generated an effective advocacy effort. Our Open Skies ratification team held meetings—both group and individual—with legislators and staffers, using statistics to highlight the concrete results of successful Open Skies agreements signed with other countries and showing Open Skies as a win-win agreement for both parties. The team spent days on the floor of the Brazilian Congress tracking how members were voting and engaging congressional staff when the vote became close. Weeks of patient, hands-on diplomacy led to the agreement’s ratification, first by the lower house in December 2017, then by the Federal Senate in February 2018. The embassy then worked with Brazilian counterparts to use the visit of Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan in May 2018 to finalize entry into force.

U.S. airlines celebrated Brazil’s entry into force of the Open Skies Agreement on May 23, 2018. One major U.S. airline will now be able to move plans forward on a joint venture with a Brazilian carrier. Combined, these two carriers transport more than 40 percent of all passengers traveling between the United States and Brazil. Another U.S. airline has since increased its investment in a Brazilian airline by more than $100 million. As a result of the new agreement, these airlines and others will be able to offer new flight options for travelers and shippers in both countries.

To put these gains in context, the U.S. commercial aviation industry supports more than 5 percent of U.S. GDP and more than 10 million jobs. Our dedicated team, both in Brazil and in Washington, made this important U.S. industry even stronger.

Transforming the Agricultural Bank of Mongolia

MONGOLIA, 2003 • BY JONATHAN ADDLETON

Khan Bank in downtown Ulaanbaatar.

Courtesy of Jonathan Addleton

An advertisement for Khan Bank over a busy thoroughfare in Ulaanbaatar.

Courtesy of Jonathan Addleton

Financial sector reform is not for the fainthearted. But the transformation of Mongolia’s Agricultural Bank is an inspiring example of what can happen when the embassy country team works together.

Ed Birgells, my predecessor as USAID mission director to Mongolia, was a major contributor, as was Pete Morrow, a financial consultant and banker from Arizona. Ambassadors John Dinger and Pamela Slutz also supported this risky endeavor, one that could have blown up in our faces.

When I arrived at post in August 2001, Pete Morrow was already several months into his new job as Khan Bank CEO. At the time it was still referred to as the Agricultural Bank of Mongolia—Khan Bank came later, when Pete tapped into Mongolia’s history to rebrand the bank and give it a new name.

The bank had been launched during Soviet times to furnish credit to herders in Mongolia’s vast countryside. More recently, during the country’s democratic era, it had been bankrupted twice, in each case following elections. After he took over as CEO, Pete often showed visitors the relevant World Bank assessment from the time, which gave little cause for optimism: “No amount of financial remediation will save this bank,” it read. “The only thing to do is shut it down.”

After the bank’s second bankruptcy, the government of Mongolia had approached my predecessor at USAID in desperation, asking for help to select and fund a new senior management team—that’s how Pete came to join the bank.

I had a bird’s-eye view of what unfolded, both as a Khan Bank board member and as the new director of a five-person USAID mission (myself, three Mongolian office staff and a driver), possibly the smallest USAID mission in the world. USAID contributed $2 million to $3 million over 30 months to support this unlikely effort to save the bank.

USAID brought Morrow in, and he ran Khan Bank like a “real” bank, demanding staff accountability and scrutinizing loans to ensure viability. He was especially effective at resisting politically motivated lending and hiring.

Usually bank restructuring involves deep cutbacks. But Morrow increased the number of branches from 269 to more than 350. He also doubled the number of staff from 800 to more than 1,600. Many of his new hires were women, and the senior Khan Bank management team remained overwhelmingly Mongolian, not expatriate. He viewed Khan Bank’s human resources as its most important asset.

Morrow introduced new computers and financial products, including a creative new pension loan that ensured elderly herders only had to travel to town once or twice a year rather than monthly to collect their modest pension checks, thus reducing transactional costs.

Remarkably, the bank turned a profit after only six months, later emerging as one of the largest corporate taxpayers in the country. Rather than receiving subsidies, it contributed mightily to the national budget.

The end game for Khan Bank was always privatization. Now that it was a successful bank, however, the government expressed interest in retaining it, at least through the next election, and some donors privately asked USAID to reconsider privatization.

But the embassy resisted this change, and we continued to work with the Mongolian State Property Committee to find a new owner. In March 2003 Khan Bank was sold to a joint Japanese-Mongolian consortium. Soon after, the new owners signed a management contract with our team, including Pete Morrow. The new owners, not U.S. taxpayers, would pay the bills. The bank sold for $6.9 million, nearly twice its assessed value.

I left Mongolia in spring 2004, one year after privatization. Five years later, I returned to Mongolia, this time as ambassador. Pete Morrow, who has since passed away, was still in Ulaanbaatar, continuing to serve as CEO. I asked him how much he thought Khan Bank was now worth. He estimated $100 million, nearly 15 times its selling price.

During the intervening years, Khan Bank had paid tens of millions of dollars in taxes. The number of bank branches now exceeded 500 and the number of employees, virtually all Mongolian, surpassed 5,000.

More importantly, Khan Bank had further expanded its loan portfolio in rural Mongolia, providing credit that helped fund tens of thousands of new solar panels, satellite dishes and motorcycles. To cite one example, the percentage of herder families placing solar panels on their gers (yurts) increased from 15 percent to more than 75 percent, illustrating one way in which the steppe was changing.

USAID also worked with the economic section and front office to promote change in Mongolia’s financial sector in other ways, including privatizing the country’s Trade and Development Bank and establishing a new microfinance bank, XacBank, which was formed by consolidating two separate USAID and United Nations Development Programme informal microfinance programs. In yet another example of effective interagency cooperation, this effort was also supported by commodity proceeds from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

All these efforts focused on financial-sector reform were largely successful, enhancing U.S. government credibility, moving Mongolia toward a market-based economy and strengthening economic and commercial ties between the two countries. They also provided unusual opportunities for USAID to work with three of the four largest private banks in Mongolia, demonstrating the success of a practical, hands-on approach to financial-sector reform in ways that benefited both the United States and Mongolia.

And this was just the beginning. The Khan Bank turnaround strengthened positive perceptions of the U.S. government in a country living in the shadow of both Russia and China. More broadly, success at Khan Bank opened the door to expanded commercial relations with the United States, most notably on the part of Boeing, which sold its first aircraft to Mongolia as the national airline transitioned toward an all-Boeing fleet; General Electric, which exported medical equipment, locomotive engines and wind turbines; and Caterpillar, which supplied heavy equipment during the rapid expansion of Mongolia’s mining sector.

Looking back, the engagement with Khan Bank remains in a special category, one that has been a point of pride on return trips to Mongolia, where the familiar green and white Khan Bank logo that was introduced by the USAID-funded management team is visible everywhere. Without a doubt, it was one small USAID mission, supported by a patient embassy country team willing to trust its USAID colleagues to take informed risks, that made this possible.

On the Economic Front Lines in the Vietnam War

VIETNAM, 1964 • BY THEODORE (TED) LEWIS

I was assigned to the joint State-USAID economic section in Saigon from 1965, when the American military buildup in Vietnam got seriously underway, through 1967, the eve of the Têt Offensive. It was a dangerous and difficult assignment, but the economic section team displayed the core disciplines of the Foreign Service: willingness to confront any challenge, no matter how daunting; readiness to accept any assignment, no matter how difficult; and determination to meet any deadline, no matter how short.

The 1954 defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu had resulted in their withdrawal from Vietnam and the division of the country into North and South Vietnam. North Vietnam was left to the communist-inclined Viet Minh (later Viet Cong), with the anticommunist Ngo Dinh Diem as president of South Vietnam. For some years the South remained quiescent, but in the early 1960s the local Viet Cong, supported by the North, became increasingly active. When the South proved unable to contain them, American military support was extended, first with advisers and then with combat troops; American troop strength reached nearly 400,000 by the end of 1966.

The military buildup necessarily injected vast purchasing power into an economy in which production, especially agricultural production, had already been disrupted. Much more money was chasing far fewer goods, with a high potential for runaway inflation. The resulting general instability would undercut or even negate the military effort. The economic section’s task was to work with the South Vietnam government to contain the inflation and assure a sufficient supply of basic goods, especially food, for the civilian population.

The pressures were unrelenting. We worked long hours, often seven days a week. Our assignments often involved the risk of being killed or captured. Yet, believing that the war’s outcome might depend on what we did or failed to do, we persevered. And as brilliantly led by the economic counselor, we largely succeeded.

The staple Vietnamese food was rice. Prior to the war Vietnam had been a major producer and exporter of rice; but because of the war rice production in South Vietnam—though the country was comprised largely of the fertile Mekong River Delta—had turned from surplus to deficit. Rural sections of the country were still self-sufficient. But the cities, especially Saigon with its two million people, were another matter. To meet their requirements, imports were needed.

The question was how much domestic production could be expected, leaving how large a gap to be filled by imports. Stock levels, both urban and rural, also had to be taken into account. We lacked reliable statistics, and with large sections of the Mekong Delta under Viet Cong control and travel in the countryside hazardous, answering this question was difficult. Yet we were able to do so with sufficient accuracy.

Pork came second only to rice in the Vietnamese diet, but supplies were easier to track: Most pigs were brought to the municipal slaughterhouse in Saigon, and figures could be obtained from its director. One of my jobs was to bicycle there once or twice a week, riding through Saigon’s streets in the dim light of early morning (slaughtering was performed before dawn on account of lack of refrigeration).

In view of urban dependence on the countryside for rice, pork and other foodstuffs, members of the economic section were required to make frequent trips outside of the city to check on conditions. Travel was in almost all instances by air, the provincial roads being too insecure to drive on. Provincial cities like Can Tho were reasonably safe, but forays into their environs were dangerous. Still, this did not deter us.

Equally important was the demand side of the inflation equation, distorted by the massive purchasing power injected by the rapid American military buildup. There was not much scope for curbing inflationary pressures through fiscal policy. Collecting—let alone increasing—taxes in the midst of the war presented great difficulty for the South Vietnam government, which at the same time had to make large war expenditures. The principal instrument remaining to curb inflation was the exchange rate.

American spending meant that abundant dollars were available to finance imports. And when importers bought dollars with piasters (the local currency), the amount they paid was taken out of the money supply, thereby reducing domestic demand. These amounts depended on the piaster-dollar exchange rate: the higher the rate, the more piasters were removed. Devaluation of the piaster was therefore essential, but it would have to be coordinated with the South Vietnam government. Further, the discussions would have to be kept secret, so as not to tip off speculators. As negotiated by the section’s leadership, both these conditions were met. Devaluation of the piaster by a third in June 1966 was decisive in ensuring the country’s economic stability and the welfare of its people.

Despite the efforts of the economic and other embassy sections, we lost the war. Were our section’s efforts then wasted? Not entirely, for they remain a shining example of economic achievement through courage and commitment.

Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation

VIETNAM, 2015 • BY KIMBERLY ROSEN AND PAUL FEKETE

Alliance Director Philippe Isler speaks at the launch of the GATF project in Morocco.

Courtesy of the Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation

For many years, USAID has supported global efforts to promote international trade and foster economic growth in developing countries. Since the early 2000s much of the focus has been on the reduction of “frictions” to trade flows—those policies and practices that constrain the physical movement of goods. Trade facilitation, as it has come to be known, is based on the acknowledgement that policy liberalization alone cannot ensure the growth of trade if businesses continue to face barriers to the movement of their products into and out of other countries.

One of the most significant initiatives undertaken by USAID in this realm has been the 2015 creation of the Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation, a public-private partnership to develop effective, private sector-based solutions to trade problems. Established with four other donors and with such multinationals as Walmart, FedEx and UPS, GATF’s objective has been to support the implementation of the World Trade Organization Trade Facilitation Agreement by making sure that the private sector is included in the development of commercially meaningful technical assistance interventions.

The WTO TFA, which entered into force in 2017, requires participating countries to minimize bureaucratic delays by border control agencies (e.g., Customs, Agriculture, Standards) that constitute a costly burden on traders. The simplification, modernization and harmonization of export and import processes—trade facilitation—will reduce average costs to WTO members by 14.3 percent and could create 20 million new jobs, particularly in developing countries. It will have a greater effect on global GDP than the complete elimination of all trade tariffs.

Vietnam is the location of one of GATF’s flagship projects. There, working with the government and the private sector, the alliance is implementing a bond system that will yield significant benefits to the business community. Since Vietnam concluded a bilateral trade agreement with the United States in 2001 and joined the WTO in 2007, it has become an increasingly important market for U.S. companies. When Vietnam joined the WTO it committed to creating a regulatory environment conducive to the operation of competitive enterprises, including smooth importation and exportation across its borders.

The project aims to reduce “hold” rates for imports and exports through the establishment of a customs bond system. Vietnam’s hold rate—the time it takes for duties and taxes to be paid and certificates to be obtained, during which time Customs holds the shipment in its physical possession—has traditionally been among the highest in Asia. By reducing hold rates, Vietnam will be able to reach its goal of becoming a more efficient manufacturing platform for the region.

It can take days or even weeks for Customs officials to release shipments in Vietnam. Their understandable concern is that once goods are released, there is no way to ensure compliance with Vietnam’s laws and regulations. At the same time, importers and exporters are unable to predict when they will get their goods out of Customs, making it difficult to plan, let alone deliver, time-sensitive shipments to domestic and international customers.

Because it is working to correct this problem, the project enjoys the support of major U.S. firms such as UPS, Ford, Intel, Amazon and Walmart, as well as local Vietnamese entities such as the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the American Chamber of Commerce in Vietnam. The project will also positively benefit U.S. companies that already sell their products in Vietnam, such as General Electric and Caterpillar.

USAID’s support of GATF advances the agency’s mission of helping our partners become self-reliant and capable of leading their own development journeys while also promoting American prosperity by strengthening and expanding markets for U.S. businesses. Reducing the time and cost of trade helps both local businesses seeking greater commercial opportunities through trade and U.S. firms that are pursuing opportunities in developing country markets such as those in Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia.

Another significant, but underappreciated, benefit of enacting trade facilitation reforms is that international businesses are more likely to invest in places where they know that red tape will be minimized, making it easier to move their goods. This can have a positive effect on development and can make U.S. businesses more competitive in the global marketplace.

Commercially Viable, Conflict-Free Gold

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2017 • BY KEVIN FOX

Aerial view of the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) community at Nyamurhale, South Kivu, DRC. Roughly 500,000 persons directly depend on ASM for survival income in eastern DRC, and it is estimated that this income indirectly benefits as many as three million family members.

Storyup

“Private sector engagement is fundamental to our goal to end the need for foreign assistance.”

–Mark Green, USAID Administrator

An artisanal miner removes clay deposits using a manual hand-scrubbing method. Processing artisanal gold is very labor-intensive, and sometimes mechanization is not sustainable on small-scale sites.

Storyup

Conflict-free artisanal gold from eastern DRC. More than 95 percent of artisanal gold—estimated at 40 metric tons per year, with a value of $1.8 billion—is mined illegally and smuggled out of the country.

Storyup

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is home to more than 1,100 mineral substances and a potential mineral wealth of $24 trillion. However, almost all of the gold from the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector in the DRC is smuggled out of the country, and revenues are often laundered in illicit schemes in Uganda, Rwanda and the Middle East. Mineral smuggling finances armed groups and militia activity in the eastern DRC, perpetuating the wider conflict that has already claimed millions of victims. Although donors have spent tens of millions of dollars to stem the flow of conflict minerals, progress has been slow.

USAID development experts and State Department diplomats recognized that co-creation and a market-based approach was needed to finally break the link between conflict and the gold trade. Toward this end, USAID implementing partners on the ground worked with ASM cooperatives to build capacity, develop traceability and certification systems, and strengthen partnerships with Congolese market actors.

Success came in August 2018 after years of engaging with those involved in both the upstream and downstream supply-chain. A USAID pilot project was able to facilitate the first export of conflict-free gold to the United States from South Kivu province in the wartorn eastern DRC. It was the culmination of years of dedicated work by officers to build trust with the private sector, working jointly to develop a commercially viable solution to a seemingly intractable development challenge.

In an interagency effort, USAID and U.S. State Department FSOs collaborated in the field and back in Washington to cultivate partnerships with responsible American companies like Google, Richline, Signet and Asahi Refining. The clean gold was exported by Fair Congo, processed by Asahi Refinery in the United States, made into gold earrings by the Richline Group and sold by Signet Jewelers through brands like Zales and Kay Jewelers. This first-ever export of fully traced and clean gold was small, but it is considered an important step in creating supply chains that are conflict-free and led by the private sector. This success led to positive press coverage from major media in the jewelry industry.

Looking to the future, USAID is working with the private sector to address the systematic challenges of conflict minerals that harm both business and the public. Within the field of international development, USAID created a more flexible procurement option that allows the government to work directly with potential collaborators and beneficiaries to “co-create” innovative approaches to tackling complex development challenges.

USAID held a co-creation workshop in Kinshasa that brought together more than 70 participants to tackle this complex challenge. Over a three-day period they developed more than 26 innovative concepts that used exciting technology like blockchain and blended tools to mobilize finance, and new approaches to encourage increased private sector engagement and co-investment to ensure conflict-free gold supply chains.

Private-sector representatives at the workshop helped develop and vet these new ideas alongside others representing civil society, donors and governments. One industrial miner even reported that he learned more about artisanal and small-scale mining in three days than he had learned in a 25-year career working in the DRC.

The new projects that will be awarded should be rolled out this winter, helping catalyze investment and financing from the private sector to increase exports of “clean” conflict-free gold and improve the livelihoods of miners. These collaborations will drive innovation at the intersection of business and development to reduce donor subsidization of responsible minerals trade and, hopefully, one day end the need for its existence.

Convincing Nigerians to Buy American

NIGERIA, 1981 • BY GEORGE GRIFFIN

I went to Lagos as commercial counselor in November 1981. At the time Nigeria was the source of our fourth-largest trade deficit because of our oil imports, and the United States was Nigeria’s second-largest export market. My job was to convince the Nigerians, since we were buying a lot of their oil, that they needed to reciprocate by buying more American goods. Competition was fierce, and the commercial section’s workload was huge.

Ambassador Tom Pickering viewed the commercial function of the embassy as one of the more important aspects of his job. He wanted a political officer as head of the commercial section, saying you can’t dissociate the two. I worked closely with the political and economic sections, and we formed a bilateral business council made up of business leaders from both countries who agreed to try to influence their governments to facilitate business. A year after the council was formed, Vice President George H.W. Bush came to Lagos to bless it.

Nigerians were not catalog or internet buyers. They wanted to touch, feel, drive or play with whatever was being sold. With this in mind, we organized big trade shows, sharing the cost with several other posts. Our primary focus was to help small American businesses who otherwise couldn’t afford to market their goods and services abroad.

Under the terms of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act we worked with only the most trustworthy Nigerian businesspeople. I tried to convince the American business community that it was not a fatal blow to have to comply with the FCPA, while making clear what would happen to them if they got caught violating it. We suggested firms should calculate what they would otherwise have spent on bribes and instead call it an immediate profit. We said the best approach was to shine a spotlight on their competitors’ bribes, something we would help them with.

The new Foreign Commercial Service Director, Rick McIlhenny, convened an all-Africa/Middle East commercial counselors’ conference in Nairobi. He insisted that we do a lot of reporting, something FCS officers were not used to doing. I calculated that during the course of my tour we facilitated $20 billion worth of business, and our trade deficit with Nigeria dropped by $2 billion in that time.

Keeping Americans Safe During a Civil War

ANGOLA, 1999 • BY JOSEPH SULLIVAN

U.S. petroleum companies have been exploring and producing oil from offshore sites in Angola for more than 60 years. Since its establishment in 1994, U.S. Embassy Luanda has worked closely with American petroleum companies as they expanded existing production, bid for newly opened exploration areas and established their operating conditions with the Angolan government.

During my time as ambassador to Angola, the final stage of the country’s long civil war erupted and the embassy’s relationship with Chevron, the largest U.S. petroleum producer in Angola, and other American petroleum companies was particularly intense on the security front. In early 1999, the provincial capital of a province where Chevron had significant operations was briefly overrun. American petroleum companies actively participated in the frequent security meetings conducted by the embassy’s regional security officer as we sought to keep each other safe and the companies sought to protect their multimillion-dollar investments. I, as well as other embassy officers, traveled several times a year to Chevron’s isolated offices and production facilities in the northern Cabinda province to meet and offer support and reassurance to the many Americans working there.

American company representatives consulted frequently with me and with the embassy’s economic/commercial officer on their plans and operations. On issues where the embassy could assist, such as the renewal of Chevron’s exploration and production lease, I advocated for the companies on behalf of the U.S. government with the Angolan government. During that same period, Exxon-Mobil consulted closely with the embassy and bid successfully on several major offshore petroleum exploration blocks. (It has since become a major producer of petroleum from its deepwater blocks in Angola.) In addition, the embassy offered advice and support as Chevron and other U.S. petroleum companies launched significant social responsibility activities in Angola.

The embassy and the oil industry worked together during this time, enabling the companies to maintain, even expand, operations and production through the most difficult and dangerous years. Since then, Chevron alone has surpassed five billion barrels of petroleum production from its fields in Angola, while Chevron and Exxon-Mobil each produce more than 100,000 barrels of petroleum a day from their Angolan operations.

U.S. Embassy Luanda supported American businesses to function in a difficult environment and worked very closely with American companies to help keep their employees and their facilities safe in the midst of a war.

NASA's New Horizons

SENEGAL, COLOMBIA, SOUTH AFRICA, ARGENTINA, U.S.A., 2016 – PRESENT • BY JOHN FAZIO AND HEATH BAILEY

U.S. and Senegalese astronomers test a telescope prior to deployment.

Courtesy of John Fazio

New Horizons project lead Dr. Marc Boie (left), Dr. Adriana Ocampo of NASA (center) and Felix Menicocci of CONAE present occultation findings in Buenos Aires.

U.S. Embassy in Argentina / Jorge Gomez

Parker Christian Hinton

Who does the National Aeronautics and Space Administration rely on to execute the most ambitious and challenging ground astronomy experiments ever conducted? The State Department, of course!

Over the past two years, teams of economic officers and their colleagues from missions in Dakar, Bogotá, Pretoria, Cape Town, and Buenos Aires worked day and (mostly) night to champion the cause of science diplomacy by supporting dozens of astronomers working on NASA’s New Horizons mission.

Launched in 2006, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft encountered Pluto in 2015 and will soon—on New Year's Day 2019—fly by a Kuiper belt object nicknamed Ultima Thule, giving planetary scientists insight into the origins of our solar system. To optimize New Horizon’s instrumentation and trajectory, NASA sent teams of astronomers overseas on five separate expeditions to collect data on Ultima Thule’s size, shape and surface reflectivity. This information will also help to mitigate risks to New Horizons on its six-billion-mile journey to the most distant part of the universe ever explored by a spacecraft.

Economic officers and other embassy personnel joined forces with NASA, coordinating logistics, addressing security issues and ensuring foreign government engagement. For example, General Services Office staff facilitated the import of telescopes and other sensitive equipment. Locally Employed staff arranged fleets of trucks and lodging for research teams in remote regions of Patagonia and Senegal, while regional security office colleagues worked with local law enforcement to ensure the safety of U.S. astronomers and their partners. Economic officers obtained host-country support and planned for future science collaboration. As New Horizons project leader Marc Buie remarked to U.S. Ambassador to Senegal Tulinabo Mushingi: “The expeditions simply could not have been executed without the flexibility of the U.S. embassy teams.”

The astronomy expeditions faced unique challenges. The first hurdle was the need for a bilateral agreement between NASA and each host-country government to facilitate the import of equipment and data sharing. To speed up implementation in Senegal, Embassy Dakar—in close coordination with State’s Office of the Legal Adviser—used an exchange of diplomatic notes, with NASA’s standard agreement attached, to get all parties pointed in the same direction in record time. Early in the process, State’s Senegal desk officer facilitated a meeting between NASA’s Office of International Relations and the Senegalese ambassador in Washington, D.C., to secure support for the expedition. Together, these actions laid the diplomatic groundwork to ensure the telescopes and astronomers would arrive on time in Dakar.

No strangers to international exchanges, economic officers facilitated this multinational cooperation and helped build the capacity of our host country partners. In Argentina, the national space agency, CONAE, connected NASA to the local resources and expertise of provincial governments, which was crucial to the success of the expeditions. The expeditions also benefited from security escorts, weather reports and the use of commercial trucks to shield the telescopes from the fierce Patagonian wind. Provincial police even closed the national highway for two hours so that lights and vibrations from vehicular traffic would not affect data collection. As NASA’s Adriana Ocampo stated: “The team succeeded, thanks to the help of institutions like CONAE, and all the goodwill of the Argentinian people. This is another example of how space exploration brings out the best in us.”

In Senegal, embassy officers worked with the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation to coordinate the participation of 22 Senegalese scientists. While these scientists had solid theoretical training, this was the first opportunity many of them had ever had to join a field expedition using sophisticated observation equipment. Senegal’s President Macky Sall also recognized the opportunity the expedition represented to build bridges of international science cooperation. Sall, a geologist by training, invited the entire expedition team to the presidential palace to celebrate this collaboration.

The New Horizons expeditions provided an unparalleled opportunity to promote U.S. leadership in science, technology and research. Local media treated NASA scientists like rock stars, highlighting their achievements through print, TV and radio interviews, as well as numerous public speaking engagements. This outreach connected NASA to local communities outside of the capital cities and influenced a diverse audience with the positive message of science diplomacy. In Dakar, the public affairs section organized a presentation on women in science by two New Horizons team members to introduce a screening of the movie “Hidden Figures,” which tells the true story of three African-American female mathematicians who made significant, but initially unrecognized, contributions to NASA’s space program.

Having organized the New Horizons visits, embassy staff took full advantage of them to stimulate future U.S. science and technology collaboration with science ministries, universities and astronomers. In fact, NASA has offered to return to Senegal in mid-2019 to present the findings of the flyby and to conduct a workshop for Senegalese planetary scientists, while Argentina’s space agency will pursue an expanded bilateral dialogue on space science. NASA plans to conduct similar astronomy expeditions in other countries over the next few years—and you can be sure the Foreign Service will be there to promote U.S. science agencies and ensure their continued global leadership role.