A Hero of Our Time: William Caldwell Harrop

BY TOM BOYATT

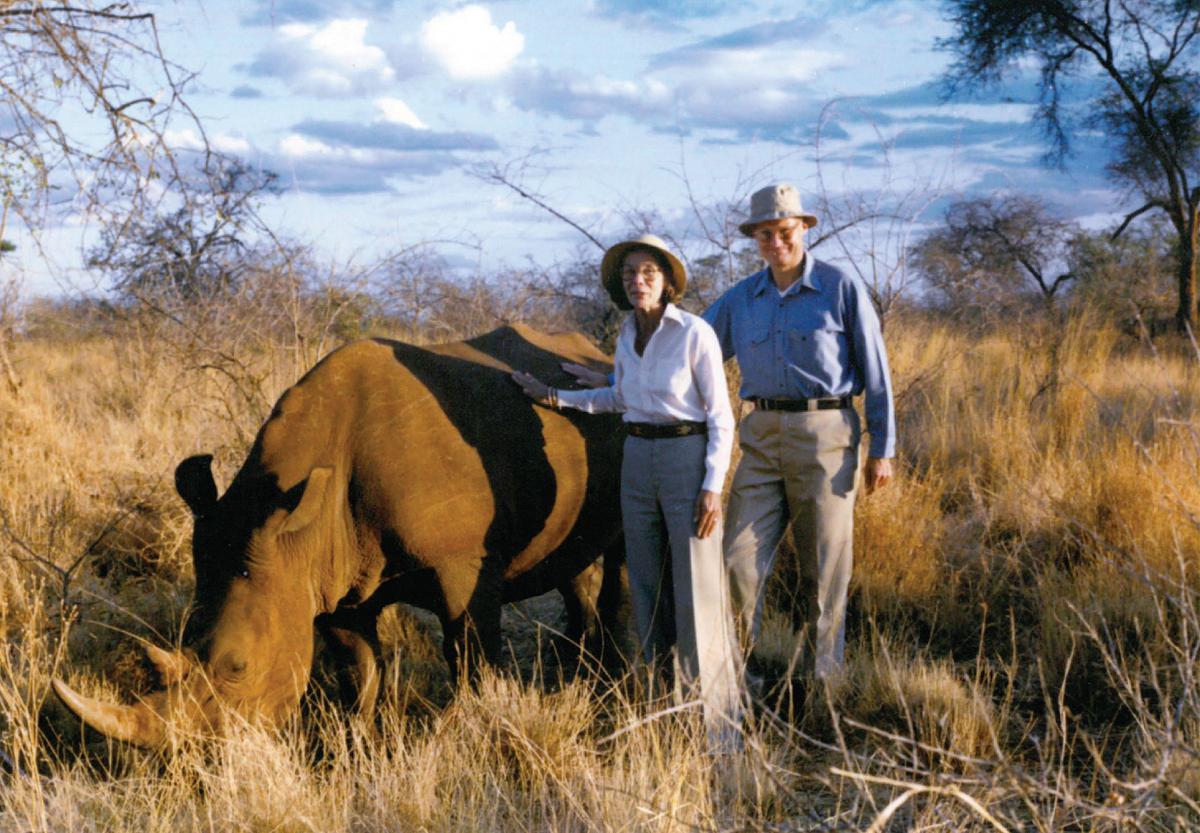

William C. Harrop and his wife, Ann Delavan, in Meru National Park, Kenya, in October 1981.

Courtesy of William C. Harrop / FSJ September 2015

In the 50 years since the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA), under the leadership of Chairman Bill Harrop, defeated the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) to become the Foreign Service union, scores of AFSA leaders and supporters have worked to strengthen AFSA in all its dimensions. The goal was and is to have the means to protect AFSA and the U.S. Foreign Service against any “existential threat.” That term was never precisely defined, so no one had a clear picture of what it would look like. Now we know.

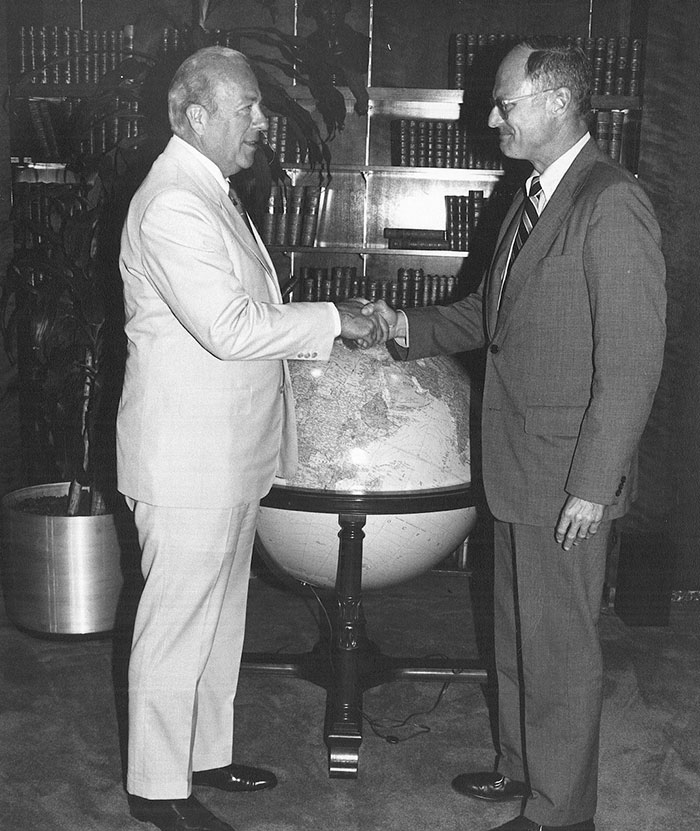

William C. Harrop, right, in his role as inspector general of the Department of State and the Foreign Service, meets with Secretary of State George Shultz in December 1983.

Courtesy of William C. Harrop / FSJ September 2015

In late March of this year, the Trump administration published a presidential executive order (EO), “Exclusions from Federal Labor-Management Relations Programs,” that purports to exclude all subdivisions of the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development from Chapter 10 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, pertaining to labor management relations, based on alleged national security reasons. The EO led to the “decertification” of AFSA as the union for State and USAID Foreign Service employees, eliminated dues checkoff, and asserted that all union contracts with AFSA were null and void.

AFSA immediately sued on the basis that the Trump administration’s actions were illegal and unconstitutional. In passing Chapter 10 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, both houses of Congress, as well as the then president who signed the law, deemed that collective bargaining and representation by a union were in the public interest. It can only be nullified or amended by the same due process of law. An executive order alone does not have the force of law since the legislative branch is excluded from the process. The EO is thus manifestly unconstitutional.

The D.C. Federal District Court granted AFSA a preliminary injunction, finding that the EO was likely to cause irreparable harm to AFSA and that AFSA was likely to prevail on the merits of its case. The administration appealed that decision to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, and it was temporarily stayed. AFSA appealed to the full Court of Appeals, which unfortunately upheld the stay. The fight continues, and a decision is expected later this year. The case will very likely go to the Supreme Court.

Fortunately, AFSA is not completely outgunned in this fight. In fact, we are a powerhouse. AFSA has a multimillion-dollar war chest to support its legal and public relations efforts, and the ability to raise much more if necessary. We have a strong congressional advocacy program, and we are also a professional association well respected among the professional and educational institutions dealing with foreign affairs.

Understanding how AFSA achieved this status over five decades starts with a testimonial to one Foreign Service officer: the late William Caldwell Harrop.

§

§

A career FSO and five-time ambassador who retired in 1984 with the rank of Career Minister, Bill Harrop was the leader of the “Young Turks” and their official inspiration during his time as chairman of AFSA (1969-1973) and then, informally, for the rest of his life.

The “Young Turks,” a group of aggressive, reform-minded middle- and junior-grade officers, controlled AFSA for three years at the beginning of the 1970s with the avowed goal of “reforming the Foreign Service.” Until then, there had been much discussion and no action. In fact, senior administrators had made it clear that AFSA was not going to dictate Foreign Service personnel policy. There was no clear path for enacting change.

Then, in October 1969, President Richard Nixon announced he would establish unions in the federal service. It was a bombshell. Neither federal managers nor employee organizations knew exactly how to react. Nevertheless, EO 11491, “Labor Relations Management in the Federal Service,” was drafted and sent to all agencies.

When Secretary of State Bill Rogers learned that the EO would make the Foreign Service part of an employee-management system under the Secretary of Labor, he demanded a separate system for the Foreign Service, reporting to the Secretary of State. The issue is said to have gone to the president, who supported Secretary Rogers.

At this point Harrop was vice chair of AFSA. He would soon become chair, when Charlie Bray resigned to become the State Department’s press spokesman. Harrop understood the enormity of the opportunity. If AFSA could become the union of the Foreign Service, we could negotiate with management to achieve desired reforms, which would then become part of official State Department regulations.

In 1970, under Harrop’s leadership, AFSA conducted a worldwide referendum to settle the question of whether a majority of AFSA members wanted to become the union of the foreign affairs agencies. Voter participation was high, and a clear majority favored unionization.

The Department of Labor was directed to supervise talks involving primarily State management and AFSA to produce a separate executive order that would establish employee-management systems for the Foreign Services of State, USAID, and the U.S. Information Agency. The resulting EO 11636 established employee-management systems in these agencies and called for union representation elections.

The provisions of EO 11636 were included in the text of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 and have been the law of the land ever since.

William C. Harrop with current and former Secretaries of State during the September 2014 groundbreaking event for the United States Diplomacy Center. From left: Henry Kissinger, James Baker, John Kerry, Harrop, Hillary Clinton, Madeleine Albright, and Colin Powell.

Courtesy of William C. Harrop / FSJ September 2015

Establishing AFSA’s Framework and Goals

The protagonists in the union elections of 1971-1973 were AFSA (20,000 members) and the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE), the 200,000-member Civil Service union. AFSA won all three representation elections by wide margins. AFSA Chairman Harrop was formally notified by the agency heads that AFSA was the certified union in each of their agencies.

Harrop quickly initiated development activities in four critical areas, which have endured and evolved over the last 50 years to give AFSA a good chance of success in meeting the challenges of today. Those areas are robust negotiations; political power; financial independence and strength—a fortress balance sheet; and maintenance of professional and Foreign Service imperatives.

Robust negotiations. Uniquely among federal unions, AFSA negotiates personnel policies and procedures agencywide. That includes bread-and-butter issues, like language incentive pay, as well as major professional issues such as promotion precepts.

Further, the broad negotiating mandate in the Foreign Service Act of 1980 enables AFSA to defend the act’s special Foreign Service provisions (e.g., “robust and impartial” entrance procedures, peer performance reviews, worldwide service, rank in person, and promotion up/selection out) from efforts by personnel bureaucrats to alter these provisions or shift decision-making power to themselves.

For 50 years, beginning under Chairman Harrop, AFSA has pursued negotiations with management to produce the most effective diplomacy possible to serve the American people.

Political power. After AFSA’s representation election victories, Harrop testified in the Senate against the confirmation of an unqualified politically appointed ambassador. From there, AFSA moved on to participating informally in the authorization and appropriation processes in both houses of Congress. Today AFSA has a fully staffed office to deal with Senate and House staff as well as our own political action committee (AFSAPAC), which facilitates personal contact with members of Congress.

In terms of wholesale politics, AFSA has significant public outreach, including a speakers program supplemented by similar efforts by other Foreign Service groups such as the American Academy of Diplomacy.

Financial independence and strength. At Harrop’s direction, AFSA’s initial negotiations included a member dues checkoff. In the 50 years since then until April this year, management collected AFSA dues at the end of every two-week pay period and sent the funds to AFSA. In addition, since the 1990s, AFSA has been governed by private-sector management norms. Our objective is an excess of annual income over costs. These “profits” are then deposited in the General Fund, which serves as a war chest and a general financial reserve. The General Fund, currently at about $4 million, is there to confront the existential threat we now face.

Maintenance of professional and Foreign Service imperatives. When it became clear in 1970 that AFSA would compete in union representation elections, the membership divided sharply over whether AFSA should compete exclusively as a union or in its dual capacity as a union and professional organization. The 1971 AFSA Governing Board elections were fought over this issue.

Harrop formed the “Participation Slate,” which argued forcefully that the union and professional dimensions would be mutually reinforcing and make AFSA the strongest possible voice of the Foreign Service. The other slate argued that the union and professional organizations should go their separate ways. In the event, the Harrop slate won every AFSA board seat. The new AFSA board promptly and unanimously elected Harrop the chairman and CEO of AFSA, and filled the other officer and committee chair positions with members of his slate, mostly “Young Turks.”

A Time of Heroes

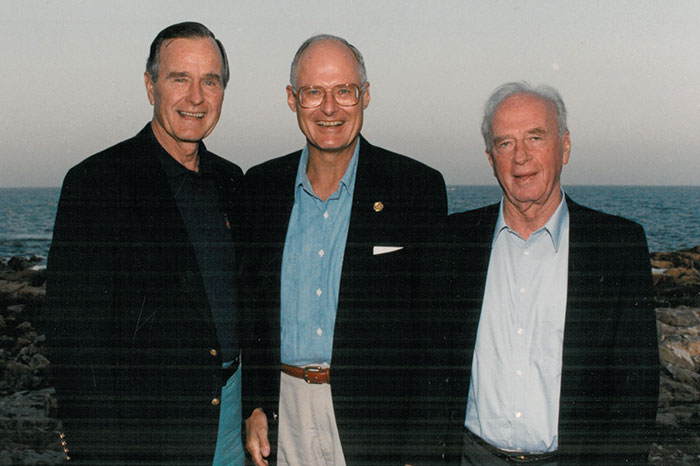

William C. Harrop, center, with President George H.W. Bush (left) and Yitzhak Rabin in Kennebunkport, Maine, on July 10, 1982.

Courtesy of William C. Harrop / FSJ September 2015

Over the last half century, Harrop ensured that AFSA’s actions and statements met the highest standards of professionalism and service. Actions do speak louder than words. For the last 50 years, AFSA members in their union negotiations activities have strongly defended the promotion up/selection out system, which guarantees that about 65 percent of the same members will not reach their highest aspirations for rank and income. Think about that.

A few years ago, then–AFSA President Eric Rubin declared that the decade of the 1970s was AFSA’s “Heroic Age.” The comment stimulated my thoughts about an earlier heroic age described by a series of poet/singers around 1000 BC in The Iliad. Late in that song, after the Greeks had prevailed over the Trojans, Odysseus, the wisest of the Greek warlords, sacrificed to the gods and gave thanks. He did not give thanks for victory; nor did he give thanks for his survival. He gave thanks that the gods had caused him to live in a time of heroes. Odysseus exalts, “I lived in the time of Ajax. I lived in the time of Hector. I lived in the time of Achilles.”

And so I give thanks and exult that I have lived in a time of Foreign Service heroes. I lived in the time of Charlie Bray. I lived in the time of Tex Harris. And I lived in the time of Bill Harrop.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.