The Life and Tragic Fate of a Young U.S. Consul

Felix H. Suau, the U.S. consul in Guadeloupe, was only 27 and had served for just three years when he perished in the earthquake of 1843.

BY SÉBASTIEN PERROT-MINNOT

The story of how Thomas T. Prentis, U.S. consul in St. Pierre, Martinique, died in the volcanic disaster of May 8, 1902, is quite famous. The general public, however, knows much less of the story of the other American consul to fall victim to earth’s convulsions in the French West Indies: Felix Henry Suau.

He lost his life in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, following the catastrophic earthquake of February 8, 1843, and after having served in his consular duties for nearly three years. I felt it was important to contribute to reviving, through this article, the memory of this dedicated and unfortunate civil servant.

§

§

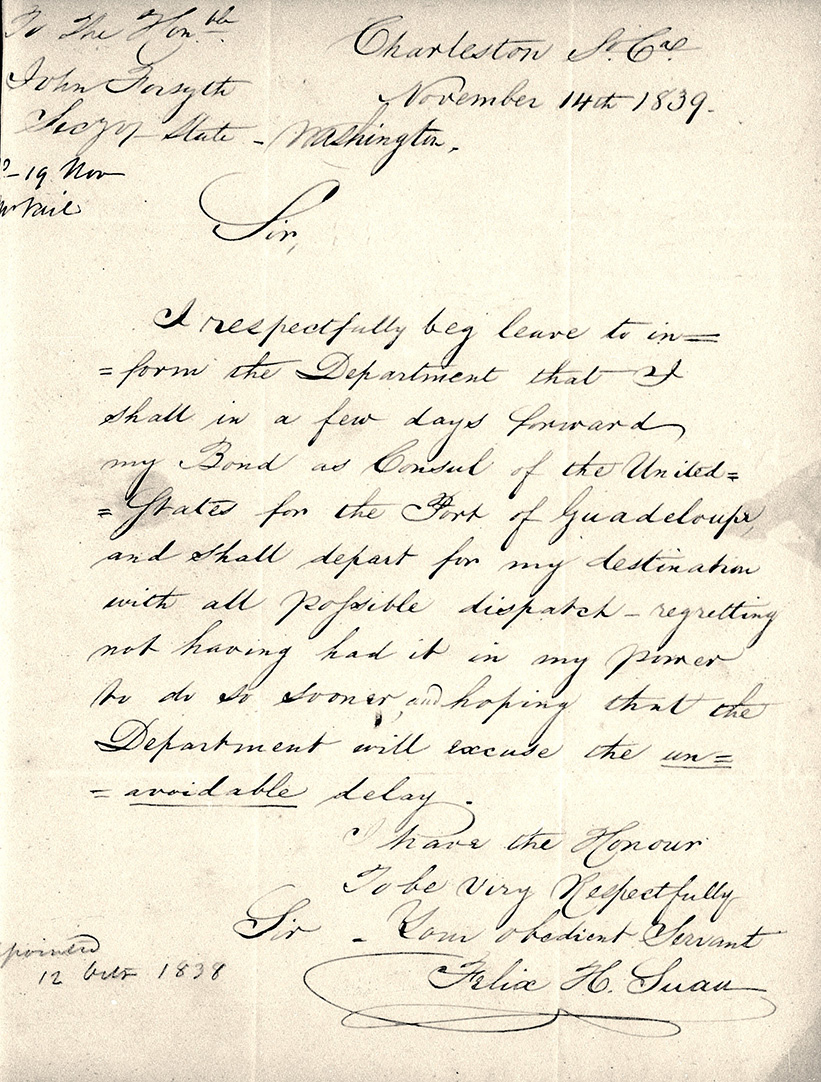

A letter from Felix H. Suau to Secretary of State John Forsyth dated November 14, 1839, informs the State Department of his plans and regrets the “unavoidable” delay.

National Archives and Records Administration

Felix H. Suau was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1815 to French parents who were naturalized American citizens: Pierre “Peter” Suau, from Bordeaux in southwestern France, and Rose Antoinette Champy, a native of Guadeloupe who died in Charleston in 1828.

Peter, a merchant, was appointed U.S. consular and commercial agent in Pointe-à-Pitre, the main port of the French colony of Guadeloupe, in 1830 and consul in the same city four years later. He was thus the first official installed by Washington in Pointe-à-Pitre. He served as consul there until his death on May 17, 1838, at the age of 73.

To succeed him, U.S. President Martin Van Buren appointed his son, Felix H. Suau, on October 12 of that year.

The corresponding documents were not delivered to the appointee until five months later, however, after the young Suau had written to “a member of Congress.” Further delays were caused by personal problems, notably health, and he did not forward his consular bond to the State Department until January 1840. Leaving Charleston on February 13, 1840, aboard the brig Alpha, he arrived in Pointe-à-Pitre on March 5. He was then presented with his exequatur, granted by the King of the French, Louis Philippe I.

In a letter to U.S. Secretary of State John Forsyth, dated February 13, 1840, Suau’s former employer in Charleston wrote that Suau had always conducted himself as “a strictly moral and honest young man.” The correspondence of the second U.S. consul in Pointe-à-Pitre with the department reveals that he was a diligent civil servant.

On May 5, 1840, in accordance with U.S. Foreign Service regulations, Suau drew up an inventory of the consulate’s property, noting the absence of the U.S. flag and arms, to be received five months later. He worked mainly in connection with the then-significant maritime trade between the United States and Guadeloupe but was also called on to assist American citizens (in particular, sailors having problems with the colony’s authorities).

At the same time, Suau worked as clerk to a French firm of ship brokers, whose associates included his brother Henry Amand. It should be noted that his income as U.S. consul was not very high: He received no salary from Washington and had to earn revenue from certain paid acts and services related to maritime traffic.

§

§

During his consular career, Suau saw his reputation attacked by a U.S. Merchant Marine captain, George Howland. In a letter dated April 16, 1842, sent to Secretary of the Treasury Walter Forward and referred to the State Department, Howland accused the consul of charging him undue sums and, more generally, of abusing his office, lacking loyalty to the United States, and demonstrating incompetence. “He is very young and unexperimented,” Howland declared, going so far as to call for the official’s replacement.

Secretary of State Daniel Webster replied on May 2—but only on the question of the allegedly unjustified expenses and largely rejecting the claims made in this regard. As for the captain’s most severe accusations, they are totally unsupported by the other historical sources available on Suau.

Another incident worth mentioning occurred in 1841, when a man introducing himself as “Colonel” Monroe Edwards gave the consul a letter purportedly from former Secretary of State Forsyth. The Secretary asked Suau to lend his full support to this “gentleman of the highest respectability” traveling on “business.”

The following year, however, Suau read newspaper reports of the arrest in the United States of Edwards, who was actually a slave trader, forger, and swindler. Forsyth’s letter of recommendation was clearly a forgery, which the conscientious consul did not fail to point out to Secretary Webster.

Published in L’Illustration on March 18, 1843, this engraving shows the destruction of Pointe-à-Pitre by the earthquake of February 8.

National Library of France

§

§

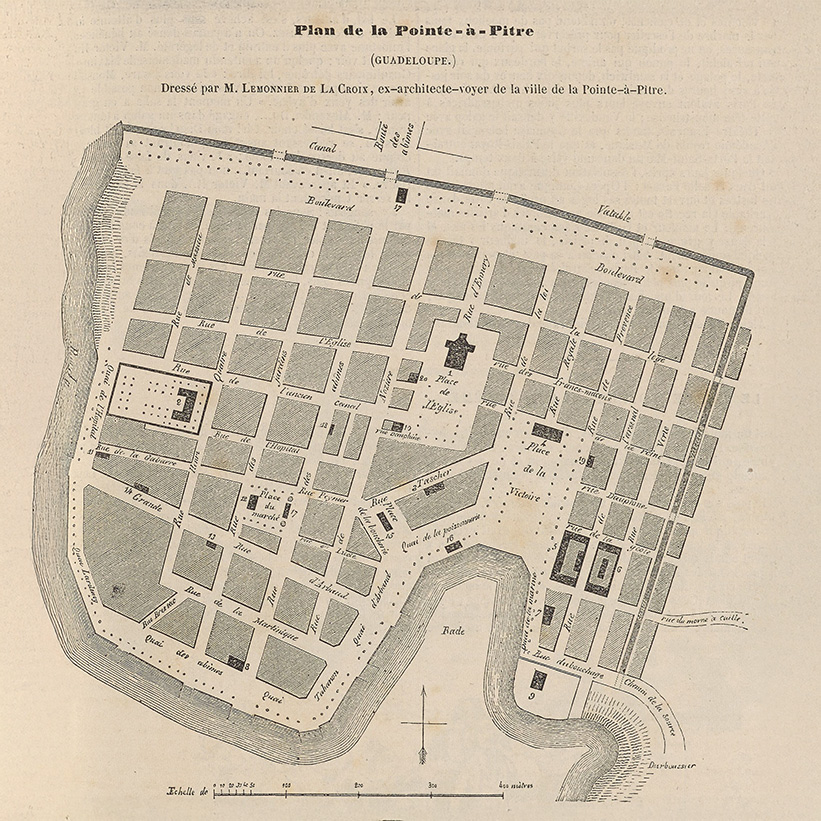

This map of Pointe-à-Pitre was published in the French magazine L’Illustration on March 25, 1843.

National Library of France

Yet Suau’s consular mission is most notable for its tragic ending. The young civil servant was in Pointe-à-Pitre on the morning of February 8, 1843, when a powerful earthquake devastated the city, then home to some 22,000 inhabitants. With an estimated magnitude of around 8.5 on the Richter scale, this earthquake had its epicenter between Guadeloupe and Antigua and was felt from the north of South America to the north of the United States. It triggered a gigantic fire in Pointe-à-Pitre, further exacerbating the disaster. As a result, between 1,500 and 4,000 people are believed to have perished in the city.

In a February 12, 1843, letter to Secretary Webster, the U.S. consul in Antigua, Richard S. Higinbotham, stated: “A French ship of war arrived here this morning from Guadeloupe and reports that the once beautiful town of Pointe-à-Pitre is now a heap of ruins and about three to four thousand persons supposed to have perished.”

On February 16, his colleague in St. Pierre, Martinique, Philip A. de Crény, wrote in a missive to the same recipient: “Among the victims [of the earthquake], I regret to be obliged to announce Felix H. Suau Esq., United States Consul for the Island of Guadaloupe, who being severely wounded was obliged to have one of his legs amputated, but did not survive the operation.”

A U.S. Merchant Marine captain who arrived in the martyred city on February 9, John G. Dillingham, indicated in a letter to his wife three days later that Consul Suau was the only American victim of the cataclysm, but we must be cautious on this point: It is known that several Americans were in Pointe-à-Pitre the day before.

In any case, Dillingham’s words are not contradicted by the (very partial) register of deaths linked to the earthquake and fire, drawn up by the municipality of Pointe-à-Pitre on February 26. According to this document, Felix Henry Suau died on February 8 aboard the American brig Rival; he was 27 years old and single.

The following month, news of the disaster spread through the U.S. press, and some articles reported Suau’s death. For example, we can read in the March 17, 1843, edition of Boston’s weekly newspaper The Liberator that “among the killed is the American Consul. He was taken from under the ruins with both legs broken and put on board an American vessel in the harbor, but died the next day” (in fact, he must have died on the night of February 8).

The fate of the consul’s remains is unfortunately unknown, but they were probably buried in Pointe-à-Pitre.

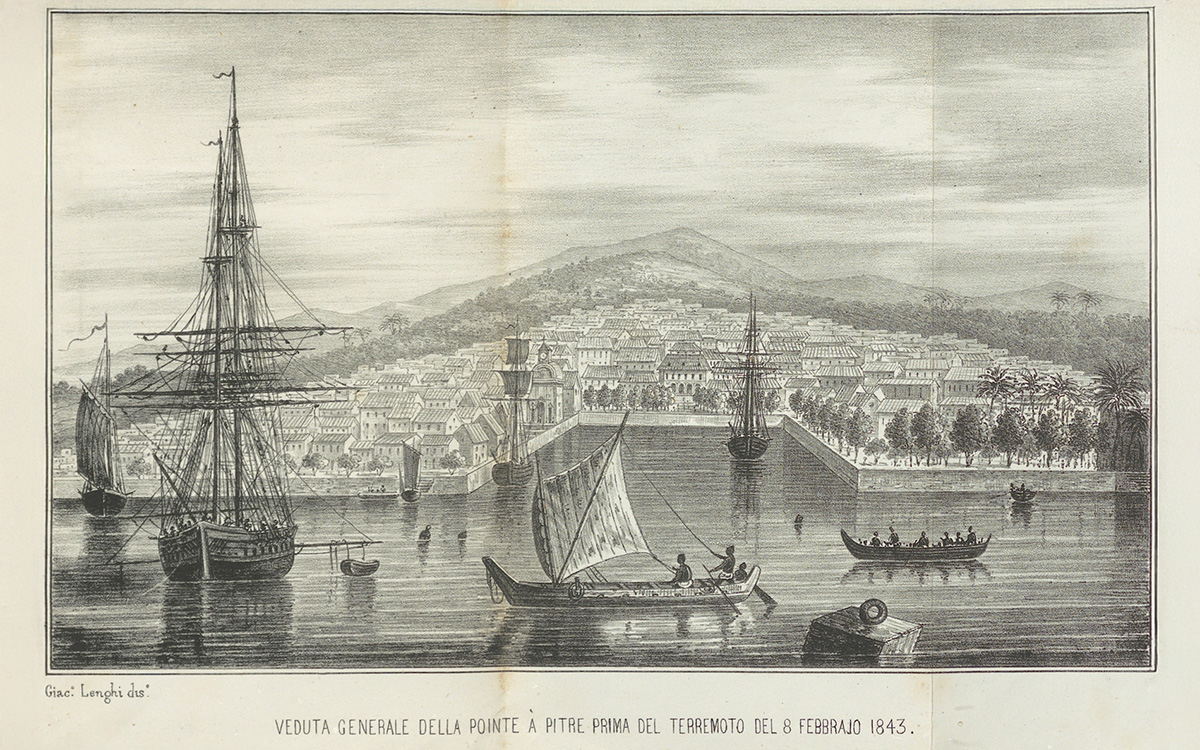

This engraving depicts Pointe-à-Pitre before the earthquake of February 8, 1843, and was published in a booklet in Naples, Italy, March 1843.

Guadeloupe Departmental Archives

§

§

The terrible toll of the earthquake in Guadeloupe prompted a wave of international solidarity, including in the United States. Pointe-à-Pitre was gradually rebuilt, and its port resumed commercial activity. As early as May 1843, U.S. President John Tyler appointed a new consul for the city: John W. Fisher, who took up his post in October.

In this geologically unstable and meteorologically turbulent region of the Caribbean, the U.S. consulate in Pointe-à-Pitre was confronted with other natural disasters. In particular, its building as well as the residence of the head of mission were destroyed by the Okeechobee Hurricane in September 1928 (but then-Consul William H. Hunt survived). The consular post was definitively closed the following year, after almost a century of existence.

As for the unlucky consul Felix H. Suau, his story has faded over time but remains linked to that of the 1843 disaster. Fortunately, as the result of diligent research by several AFSA members, his name was inscribed on the AFSA Memorial Plaques in the C Street lobby of the Harry S Truman Building in 2021. Researchers had identified a total of 56 diplomats and consular officers dating back to 1794, whose deaths were unknown when AFSA unveiled the original plaque in 1933. The AFSA plaques honor Foreign Service members and pre-1924 diplomats and consular officers who died under circumstances distinctive to overseas service for the U.S. government and American people—and the young consul, Felix H. Suau, is now among them.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “The Unlucky Consul: Thomas Prentis and the 1902 Martinique Disaster” by William Bent, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2020

- “Memorializing the U.S. Consular Presence in Martinique” by Sébastien Perrot-Minnot, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2022

- “Once Upon a Time: The U.S. Consulate in Martinique” by Sébastien Perrot-Minnot, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2023