Returning to U.S. Schools: A Guide to Transcripts and Smooth Transitions

Here’s what’s involved in aligning international school transcripts with the requirements of a U.S. public school.

BY REBECCA MCPHERSON

Resources

- GCLO Education and Youth web pages: https://www.state.gov/global-community-liaison-office/education-and-youth/

- Office of Overseas Schools Parent Resources: https://www.state.gov/resources-office-of-overseas-schools#parents

- Senate Bill (SB 1244) Expansion of Policies to Students Transferring from Foreign Countries: https://legiscan.com/VA/text/SB1244/2025

- Third Culture Kids (3rd ed.), by David C. Pollock, Ruth Van Reken, and Michael Pollock: https://amzn.to/49cxpBK

Transitions are familiar territory for Foreign Service families: packing up household items, attending farewell gatherings, and preparing for new assignments. These transitions come with a range of challenges such as choosing the right school for your children or trying to register without a permanent address.

One major concern can be aligning international school transcripts with the requirements of a U.S. public school, particularly for high school students.

The Global Community Liaison Office (GCLO) education and youth team understands the importance of facilitating a smooth academic transition and the complexities of placing students in the appropriate courses and grade levels upon their return to the United States.

The team took the opportunity to talk with administrators in Northern Virginia school districts as well as international guidance counselor Ryan Haynes and Regional Education Officer (REO) Andrew Hoover in the Office of Overseas Schools to provide guidance and tips to maneuver the transcript and transfer process successfully.

Understanding Transcripts

Academic transcripts serve as the official record of a student’s academic journey and include course titles, grades, credits earned, verification of course completion, standardized test scores, cumulative grade point average (GPA), and honors and award distinctions. They provide a chronological academic history of a student.

“It is important to note that transcripts don’t necessarily tell the whole story of a student,” notes Katie Server, family partnerships specialist for Fairfax County Public Schools. Server recommends that students share additional information that can help a school understand the larger picture of who they are as a student, such as asking teachers to write recommendation letters and providing details of extracurricular interests.

Creating a portfolio of the topics covered during a semester shows what was covered beyond the test scores; even submitting a sample of completed work can be helpful.

Being proactive by collecting and providing this information even before the international school sends the official transcript can help with the enrollment process. Server adds that schools will also want to see attendance and disciplinary records.

Andrew Hoover, REO for East Asia and the Pacific, says it is important to understand the difference between official transcripts, which are produced after a semester is finished, and unofficial transcripts.

The official transcript reflects the student’s completion of their courses of study. So, if the student leaves prior to the end of a semester, the transcript will be incomplete, and the student may get only a progress report or an “unofficial transcript” to take with them.

REOs and guidance counselors advise families to be flexible as the receiving school will have to resolve any issues with course credits.

Transcript Evaluation

Since there is no universal system for translating and evaluating transcripts, aligning curriculum standards and coursework between international schools and U.S. public school systems can present complications.

The evaluation process often involves deciphering different grading systems. Grades can be letter-based or percentage-based, strictly pass/fail, narrative, or standards-based, and grading practices can vary depending on the policies of individual schools or teachers, as well as the overall academic performance of the class. These differences can complicate the evaluation of an international transcript when transferring and assigning credits and determining appropriate course or grade placements in a U.S. school.

Working closely with guidance counselors from both schools and understanding their roles is vital.

Course equivalency determinations and verification of the completed coursework, credit transfer limitations, and noted gaps in the sequential learning process, especially in math and foreign languages, are common challenges that can affect the student’s placement outcome.

If the student is arriving from an international school in the Southern Hemisphere or is a midyear transfer, there may be questions as to the appropriate grade level to place them in. Standardized test scores may be missing, and records may be incomplete or delayed, causing a lapse in obtaining the official transcripts.

The Role of Guidance Counselors and Regional Education REOs

Early and frequent communication with both sending and receiving schools is crucial for a smooth transition and for parents and students to advocate for proper credit assignment and class placement.

Working closely with guidance counselors from both schools and understanding their roles is vital. Counselors at the receiving school in the U.S. will review the core subjects (typically math, science, social studies, and language arts) to ensure they align with U.S. standards. They will also assess grades and test results to confirm whether the student has made appropriate progress and demonstrated academic growth.

Additionally, they will verify that the sending school is U.S.-accredited or that the transcript and academic records are authenticated by another educational authority to validate the student’s credentials.

Guidance counselors also look at attendance records, extracurricular involvement, standardized test scores, and evidence of consistent academic performance. Any evidence of disciplinary actions is also considered. They will review supplementary instructional materials and discuss concerns with the family before making a final evaluation and recommendation.

Ryan Haynes, director of Upper School Personal and Academic Counseling at Taipei American School, advises students to go a step further and communicate with the receiving school the courses they were planning to take the following year and share the course catalog and course descriptions.

REOs can help coordinate with international school counselors to facilitate the transcript transition.

If there are questions about course titles or content, Rebecca Sharp, executive director of student services in Falls Church City Public Schools (FCCPS), notes that providing a course syllabus or curriculum plan and course outline can help confirm the rigor and depth of a subject and whether it is grade-appropriate.

The REOs can help coordinate with international school counselors to facilitate the transcript transition. As Andrew Hoover states, “We recognize there are transcript translation challenges—if you transition to the U.S., you, as the parent, may be responsible for managing the translation of the transcripts, and I don’t mean from a foreign language.”

The REOs meet with counselors during post visits and will consult with families so they know what questions to ask and how to prepare. In some cases, according to Hoover, the origin school may arrange for a high school student who leaves midsemester to do some kind of extended learning so that the student can enroll in a U.S. public high school and yet receive the final course credit from the origin school.

He also notes that it may be helpful to share the origin school’s high school profile to show what the learning experience is like as additional information for the new school.

IBDP and AP Considerations

For students coming from an IB Diploma Program (IBDP), careful examination is needed to align courses with those available at the new school. There could be continuity challenges if a student is in the middle of an IBDP because there are often differences between course offerings at schools.

Also, higher-level IBDP courses last for two years, so careful consideration must be made to ensure continuity.

Most AP classes are one year, so they do not pose a challenge to transcripts unless the student is moving during the school year.

If a student is planning to take several AP classes during high school, it is important to confirm the offering at the new school. If a school does not offer the course, it might be possible to find an authorized online AP course.

Overall, when moving during high school, connecting early with the guidance counselor to discuss these situations is highly recommended.

For families in the bidding process, Haynes suggests researching schools that have pivoted from traditional IB methods of integrated math and science to the U.S. standards of learning, where the courses are stand-alone (e.g., geometry, algebra 1 or 2, and sciences such as biology and chemistry).

This makes it easier should the student return to the U.S.

Impact and Support

It is important to recognize the impact that these challenges may have on a student. Feeling pressure to adapt to a new school setting and prove their academic competency is not uncommon. Parents and schools can provide support by acknowledging how the transition affects the student. Academic advising and student support services are available to help.

Haynes points out that the goal is “leaving well to arrive well,” and that many schools offer transition programs or dedicated orientations to help both the students and parents. International guidance counselors familiar with Foreign Service students may share the principles of the stages of transition and the importance of building a RAFT or using a RAKE.

The RAFT is about leaving well: Reconciliation, Affirmations, Farewells, and Think Destination. It involves making time to resolve any conflicts or unfinished projects, showing gratitude and saying thank you, prioritizing proper goodbyes, getting excited for a new experience, and preparing for what lies ahead.

Using the RAKE model—Reconciliation, Affirmation, Keep in Touch, and Explore—helps guide and encourage students and parents to arrive well.

“The three most important things to provide a receiving school in the U.S. are the names of courses, credits awarded, and grades earned,” says Sharp. “It is also imperative for parents and students to review the state graduation requirements to make sure the student is in line for an on-time graduation.”

Overall, when moving during high school, connecting early with the guidance counselor is highly recommended.

Sharp also notes that FCCPS, for example, will start the registration process without a permanent address on file since they are accustomed to working with Foreign Service families.

Parents can begin communicating with FCCPS schools two to four weeks ahead of the official registration date, and students may opt to apply to and attend an IB school if there is no program within the boundary they are zoned for, if space is available.

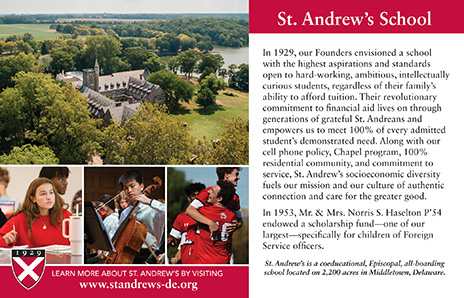

In March 2025, Senate Bill 1244 became law in the state of Virginia. The bill, which went into effect on July 1, provides additional support to ease transitions for returning families and expands the provisions of law relating to educational opportunities for students of certain federal employees who are transferring from a school in a foreign country to a school division in the Commonwealth by establishing definitions for the terms “foreign education agency” and “sending country.” (See page 67 of the April-May FSJ for more.)

The bill amends Virginia’s education code to simplify school enrollment for children of federal employees returning from abroad, allowing provisional enrollment with unofficial records, honoring previous educational placements, and promoting the on-time graduation of students if similar coursework has been completed in the sending country.

School transitions and transcript evaluations can be successfully maneuvered with proactive communication from students and parents and support from both schools involved in the process.

With the right resources and timely preparation, families can experience smoother transitions and help their children to succeed in a new academic environment.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Transitioning FS Kids to U.S. Public Schools: What You Need to Know” by Charlotte Larsen, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2022

- “What You Need to Know: Returning to U.S. Public Schools with Special Education Needs” by Charlotte Larsen and Rebecca McPherson, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2022

- “Navigating the Foreign Service Educational Landscape” by Rebecca McPherson, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2024