Scooter Wisdom: Life Lessons from the Streets of Saigon

For this author, commuting via scooter offered valuable lessons in how to survive—and thrive—in a complicated world.

BY JOHN HARRIS

A local family travels through Ho Chi Minh City in style, 2023.

Jannen May

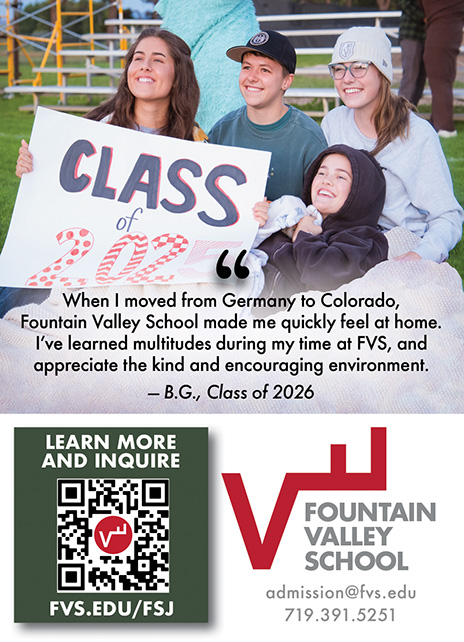

As we prepared to move to Vietnam two years ago, which we often did in our itinerant Foreign Service lives, we found ourselves looking around for cultural portals through which to learn about our new home. Given the rich history of the country, not to mention our complex bilateral relationship, there was much to choose from. An obvious place to start was Anthony Bourdain’s decades-long obsession with Vietnamese cuisine, or Ken Burns’ searing history of what is referred to here as the “American War,” or Viet Thanh Nguyen’s extraordinary novel, The Sympathizer, now an HBO series.

Somehow, however, it was the BBC’s hilariously absurd “Top Gear” episode about three middle-aged Brits’ disaster-strewn motorcycle trip from the south to the north of Vietnam (more than 1,000 miles) that really spoke to us. This wacky adventure stuck with me as we subsequently made our way around the country. I began to see the streets as one massive and connected organism, made of millions of individual parts but somehow behaving coherently as a united, kaleidoscopic whole.

USAID’s Samir Goswami visited the Selex Motors factory, which manufactures electric scooters and batteries, on February 27, 2024.

USAID Vietnam

§

§

Commuters on scooters navigate the crowded streets of Ho Chi Minh City, 2023.

Jannen May

Of all the planet’s megacities, few are as synonymous with motorcycles and scooters as Saigon. Saigon—or Ho Chi Minh City, as it has been officially named since reunification in 1976 (though its residents use the two names interchangeably)—pulses with relentless two-wheel energy. Several roads are designed exclusively for scooters, and many of the city’s gleaming new bridges across the storied Saigon River have dedicated, walled-off, scooter-only lanes. Cars are an annoying afterthought; unlike the capital, Hanoi, its northern, traffic-filled rival where cars choke the streets, Saigon is resolutely of, by, and for the scooter. Driving a car, you feel like a whale swimming through a school of nimble fish, moving slowly, deliberately, in a traffic pattern ruled by packs of agile, darting scooters.

With a population of nearly 10 million in Saigon, with likely at least as many scooters, its streets should be noisy and polluted. But every year the streets get cleaner, mostly because of the rise of electric vehicles (EVs). With U.S. government support, Vietnam is now a global leader in EV technologies. Two-wheeled EV entrepreneurs, in particular, are booming and, in some cases, preparing to export their technologies to the U.S. Keep an eye out for Vietnamese start-ups, like VinFast, DatBike, and Selex, any one of which may change the global EV market in the decades to come.

I rode my scooter daily on my way to work for USAID at the U.S. consulate in downtown Ho Chi Minh City. The consulate was built at the site of the pre-1975 U.S. embassy, known from images of last-minute helicopter evacuations of Americans and American-aligned personnel in April 1975. When I first sallied forth into Saigon’s scooter-centric soul, I thought I was entering chaos. In time, with the benefit of two years of scooter driving behind me, I’ve learned that Saigon’s two-wheel universe actually brings the possibility of serenity—even profound life lessons—if you approach the task with an open mind.

To absorb many of life’s great lessons, you just need to jump on a two-wheeler and ride around the city.

In Saigon, being right is less important than being accommodating. Sure, there are rules on the books. In practice, however, nearly anyone can do nearly anything, anytime. In the absence of crosswalks, pedestrians cross even crowded thoroughfares at will—miraculously, nearly always successfully. With traffic lights a rarity, diverging traffic finds its way through confusing intersections with astonishing smoothness. The near absence of accidents despite the chaos would baffle someone trained in a more rules-oriented system. (Just think of U.S. streets when a traffic light fails.)

Rules, of course, are important. But so is a bit of flexibility and imagination. On the streets of Saigon, everyone is accommodating. Scale the approach up to the national level, and this results in Vietnam’s famous “bamboo diplomacy,” which enables Vietnam to exist in a confusing, contested part of the world and remain everyone’s trusted partner. Recently, in less than a year, Vietnam hosted the presidents of the U.S., China, and Russia. The secret of how Vietnam can pull off that extraordinary balancing act may be found in the functional chaos of its streets.

Wise riders head for openings, not closings. There is a clearly understood hierarchy on the streets of Saigon. In general, size gives precedence. Buses, for example, proceed deliberately into chaos, fully understanding that everyone will scatter by the time they arrive. Scooters, at the lower end of the size/priority continuum, must be considerably more agile.

USAID Administrator Samantha Power rides an electric motorbike in Hanoi, March 10, 2023.

USAID Vietnam

Crossing the river at night in Ho Chi Minh City, 2024.

Hannah Harris

Wise two-wheel pilots move toward openings, not closings. If the car just ahead unexpectedly signals that it’s making a U-turn, wise riders accept this fact and time their arrival after the offending four-wheeler has cleared, even if the rules of the road are in their favor. Scooters in Saigon are pint-size, scrappy survivors. Adjusting to circumstances to find a path forward is much more important than analyzing what has gone before; what exists is much more important than what should be.

The entire spectacle reminds me of the central tenet of improvisational theater: Always accept what has gone before and build on it. Scootering around Saigon teaches you to embrace the unexpected and thrive amid chaos, a valuable life skill.

There are different ways to know what’s coming. In the relatively few intersections where traffic lights are operational and respected, scooters quickly build up behind the red light. Jostling to get ahead, scooters soon fill the road space in front of the light as well, beyond where the traffic light is visible. You would have thought that these drivers would be at a disadvantage, not knowing when the light behind them turns green.

But there’s more than one way to know when to proceed. These forward-leaning riders, for example, unable to see the green light behind them, are listening for the rev of engines instead. When enough engines rev, they can safely assume that light must have changed. You don’t have to have seen the light to know that it has changed.

Watching this dance reminds me of the role of a diplomat overseas. You can read the news and digest the headlines, no matter where you are in the world. But to truly understand a place as nuanced and multifaceted as Vietnam, the only way to fully succeed is to be here, on the ground, using all your senses.

Proceed with caution, but proceed. On a scooter in Saigon, it is rare to have open road in front of you. There is almost always something alarming unfolding ahead. A sensible approach would be to slow down, perhaps even stop, until you can see a safe way through. Wise riders, however, continue toward the obstacle—safely, for sure, but resolutely. Nearly always, as you approach the obstruction ahead, conditions will have shifted by the time you arrive, allowing you to safely pass. You may not take the path you originally intended, and you may have to get creative in your approach. But pass you can.

This got me thinking about uncertainty and opportunity—two omnipresent truths of our lives overseas as FSOs. Who knew that scooters in Saigon could be such eloquent instructors of this critical diplomatic lesson? My experience has convinced me that a good deal of what you need to know about life, you can learn while navigating Saigon’s scooter traffic.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Doing Social Work in Southeast Asia” by Lange Schermerhorn, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2015

- “Vietnam and the United States: The Way Ahead” by Ted Osius, The Foreign Service Journal, April-May 2025

- “Peace, Cooperation, and Global Progress: 30 Years of Vietnam-U.S. Diplomacy,” by H.E. Nguyen Quoc Dzung, The Foreign Service Journal, April-May 2025