In Their Own Words: FS Family Members on Writing

Four writers who are FS family members talk about their paths to publication.

BY DAVID K. WESSEL

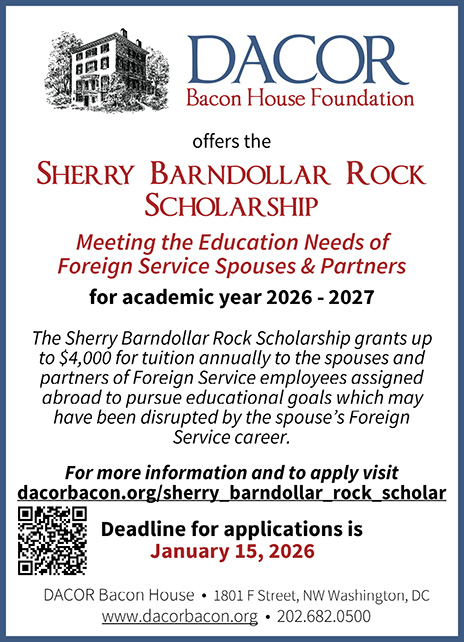

Author Matthew Algeo signing books at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, Independence, Missouri, November 14, 2023.

Courtesy of Matthew Algeo

Each November The Foreign Service Journal features the recently published literary works of many members of our community. Memoirs, biographies and histories, books on international relations and diplomacy, adult novels and children’s books, poetry collections, and guidebooks highlight the creative talents, mental energy, and writing skills that so many FS community members possess.

In this article, four current and former eligible family members (EFMs) share their experiences as authors and how their writing journeys have been influenced by living the life of a “trailing spouse.” Matthew Algeo is a history writer, radio show host, and the spouse of a recently retired Foreign Service officer (FSO). Matthew Becker is an EFM currently living in Nicaragua and the author of a three-novel thriller series. Derek Corsino is a culinary artist, educator, and the spouse of a first-tour FSO stationed in Shanghai. And Tomoko Horie, a former television journalist, is currently based in Hong Kong with her second-tour FS spouse.

This past spring the four authors, spread across the globe, were sent a common set of questions regarding their paths to publication. Their email responses were collected over the summer months and collated for this article.

§

§

Matthew Algeo

Courtesy of Matthew Algeo

David K. Wessel: Have you always wanted to be a writer?

Matthew Algeo: I was always a good writer and not cut out for manual labor, so it seemed a natural course. I majored in folklore in college, a sure sign I wouldn’t be pursuing a career in, say, chemical engineering. After college I drifted into journalism, mainly working as a reporter at public radio stations all over the United States.

I sold my first book in the spring of 2005. I signed the contract, and that night my wife and I went out to celebrate. We awoke groggily the next morning. Allyson checked her email. The State Department was offering her a spot in the next A-100 class. Our lives were upended in the course of a day! She accepted the offer, and we moved to Washington, D.C., for training. Over the next 20 years, we would live in Bamako, Rome, Ulaanbaatar, Maputo, Sarajevo, and Gaborone. Along the way I would write eight books.

Matthew Becker: I never considered being a writer until my late 20s. My writing career is entirely based on my love of reading and a random thought one summer that since I had read enough thrillers, I could come up with a plot of my own. I decided that I might as well write it and see. Flash forward a few years, and here we are!

Derek Corsino: Writing a book was never on my “things I must do” list, but it began to creep up as something I as an educator wanted to do.

Tomoko Horie: Three years ago, I left my corporate job and became a freelancer. Since then, I started wanting to make writing my profession; I wanted to write a book. Now, I am working as a writer.

I enjoy researching the books more than I enjoy writing them, to be honest.

–Matthew Algeo

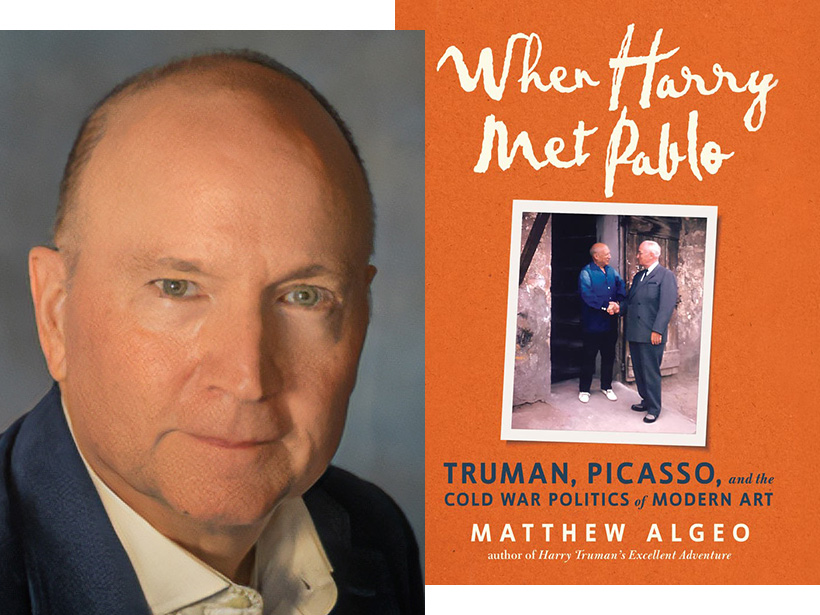

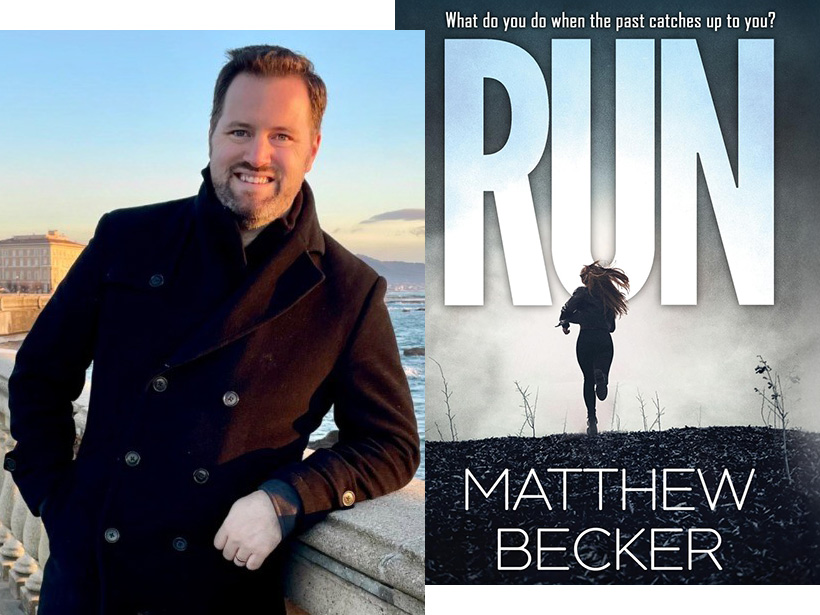

Matthew Becker

Courtesy of Matthew Becker

Wessel: Where did the idea for your first book come from?

Algeo: I write nonfiction, so all my books have been based on true stories, usually some small event that illuminates a larger issue. For example, Harry Truman’s Excellent Adventure tells the story of a road trip that Harry and Bess Truman took in the summer of 1953, shortly after they left the White House.

At that time ex-presidents didn’t receive pensions or Secret Service protection, so it was just the two of them driving cross-country in their Chrysler, staying in motels and eating in roadside diners. So, more than just the story of their trip, it’s the story of life in America in the middle of the 20th century.

My most recent book, New York’s Secret Subway, tells the story of the city’s first subway, a pneumatic-tube line built clandestinely, but at the same time looks at the history of mass transit and politics in the Gilded Age.

Becker: There is that piece of fleeting hope you hold on to when a loved one has been involved in some sort of tragedy but hasn’t been confirmed as a victim yet. In real life that normally ends only one way, so I wanted to construct a story where there was more than met the eye. Now I have so many ideas I’ll never get through all of them.

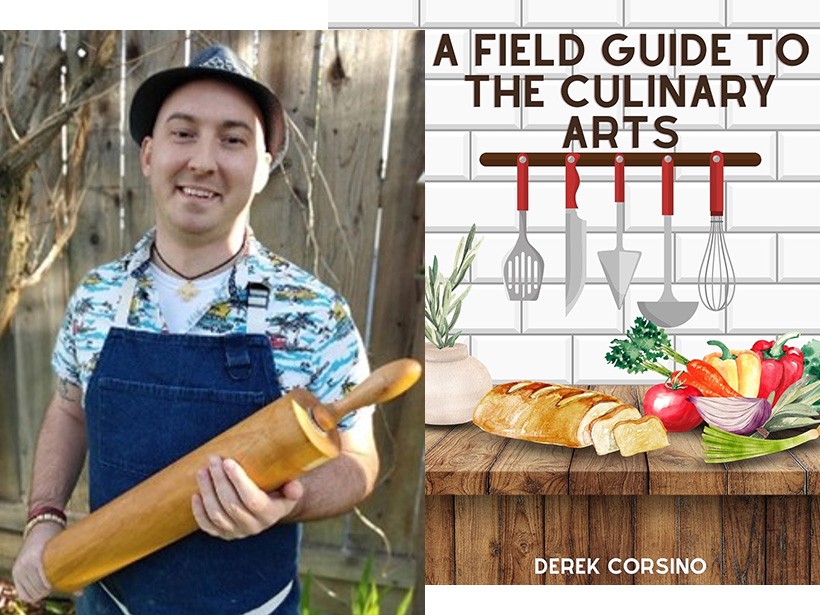

Corsino: This first book stems from my students and curriculum. I thought of what I do in my introductory culinary arts classes and how I developed that successful curriculum. Then, I moved from there toward how the average person may want to learn.

Horie: My husband’s first overseas assignment was in Tanzania. I thought it was a very special and rare opportunity to live in Africa, so I wanted to document my experiences there. But I figured that if I wrote only about life in Africa, people who aren’t interested in Africa wouldn’t read it, so I decided to write about the challenges people face in their 40s and how I dealt with those challenges while living in Africa.

Derek Corsino

Courtesy of Derek Corsino

Wessel: What do you most—and least—enjoy about writing?

Algeo: I enjoy researching the books more than I enjoy writing them, to be honest. I like nothing better than walking into an archive or library or historical society with a list of items I want to look up. It’s exciting to me. Most research trips don’t yield much, but once in a while, you find a gem. Maybe it’s an old letter that Harry Truman wrote to a friend about his road trip, or a ticket to ride New York’s first subway, or photographs about the story you’re researching that have never been published before. That’s the best part, the hunt for those little bits and pieces that together complete the story.

Becker: I love writing the twist, writing those lines where everything you thought you understood is flipped on its head, and imagining readers’ reactions when they get there. That’s a large part of what I’m in it for. Most of my novel ideas start with “what if we thought x … and then it was actually y.”

The chapters I enjoy writing the least are those right before a big reveal or twist. I’m so desperate to get there that it can sometimes make it feel like a bit of a slog doing that final buildup. But it’s vitally important not to rush those!

Corsino: My book is primarily recipes; much of it was already written and extensively field-tested from years of student successes and failures. What was fun was reimagining some of them to work better in a home kitchen and reformatting them for home use and not industry use. I had to change the tone and vernacular quite a bit.

My least favorite part of writing a book was all the formatting and editing it requires. I self-published, so I built and edited the entire thing in-house. If a page number did not line up well with a particularly large recipe, I needed to edit all 117 pages.

Horie: I enjoyed writing about the surprising experiences I had in Africa and how they completely overturned my previous assumptions.

Tomoko Horie

Courtesy of Tomoko Horie

Wessel: Please describe your journey from the idea stage to publication. How has being part of the Foreign Service community helped during your publishing journey?

Algeo: In some ways it was an ideal situation. Whenever we were in Washington, D.C., I could do most of the research. A lot of what I needed was in the Library of Congress. Then, when we went back out for a tour, I could do the writing. Of course, when the book was published, I would have to fly back from Mongolia or Mozambique to promote it in the States, but that’s the way life goes in the Foreign Service. And I could always count on our FS friends to show up for my events!

Becker: I did the classic querying into every agent’s slush pile, hoping for that one break. What ended up happening was things working in the opposite direction. While waiting for agent responses, I saw that my publisher at the time had opened a thriller imprint and was willing to accept submissions directly from authors. They liked my manuscript and offered me a three-book deal.

In the meantime, I was able to get an agent, who has been wonderful ever since. As with so many writing stories, it all moved very slowly until all of a sudden, it was a runaway train. We just completed that contract, and now my agent and I are discussing what we want to do next.

The Foreign Service community is an extraordinarily supportive group. We’re all doing this thing together and having experiences that are difficult to fully get across to anyone outside this life. So for me it has been having a built-in community of people who care about you and your successes and are rooting for you.

Corsino: It took about two years from start to finish, but really a month of constant work. I knew I wanted to write recipes, but I struggled with what the customer needed. Also, as culinary trends changed, my scope would get thrown out. So I opted for something more specific and broader in subject matter. That first book was done prior to my wife’s first tour, but that lit a fire under me to get it done.

My next book, which is in development, is looking at a trend that is speculative but should be a hit right when it comes out. It’s important to always know where they are going in culinary research and development.

Horie: At first I wrote in Japanese for a Japanese audience. Later, some American colleagues and friends said they wanted to read the book, so I decided to publish it in English as well. As a writer, I want to share new learnings and insights from the countries where I will live in the future through articles and books. Being part of the Foreign Service community provides me with that environment, and I am grateful for it.

I did the classic querying into every agent’s slush pile, hoping for that one break.

–Matthew Becker

Matthew Becker, with the first two books in his murder mystery trilogy. Run, a psychological thriller, was published in 2024, and Don’t Look Down followed in 2025.

Courtesy of Matthew Becker

Wessel: Did your Foreign Service life hinder your writing journey in any way? If so, how?

Algeo: Yes, undoubtedly it was difficult to do some research overseas, especially in the early years of Allyson’s career. I often had to hire researchers to look things up for me in the States. As the years went on, however, more and more archival material could be found online (especially newspapers), so this became less of a concern. I should mention, too, that I always tried to find a place to do my writing, either in a library or a shared workspace. I have library cards from Rome, Ulaanbaatar, and Sarajevo!

Becker: The biggest hindrance is the distance away from writing events, whether launch parties or big conferences. There’s no replacement for face time with readers (and other writers, editors, agents).

Corsino: No. As an EFM, and with a hiring freeze while being in a country with no bilateral work agreement, I find myself with an immense amount of time to write.

Horie: Not at all.

Wessel: What advice would you offer other aspiring Foreign Service authors?

Algeo: Write what you want to write, not what you think you can sell. If you write nonfiction, take note of all the times you’ve thought “I’d like to read a book about that,” and write that book. Fiction is much more difficult to sell (and to write, I believe). The nice thing about writing nonfiction is that you don’t have to write the whole book before you sell it, you only need to write a detailed proposal.

Becker: Find a community of writers. It doesn’t matter who, and you certainly don’t have to share your writing; but having people to talk to throughout a process that is filled with rejection at every step is a must. I am super chatty, so come talk to me!

Corsino: Give it a shot, and when in doubt self-publish!

Horie: Publishing a book might seem intimidating at first, but nowadays it’s easy to self-publish without going through commercial publishing. Plus, not everyone gets the chance to live abroad, so I encourage you to consider publishing with the mindset of sharing what you have seen and experienced with others.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “A Bibliography of USAID Authors” by John Pielemeier, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2015

- From the FSJ Archive: FS Spouse Employment, The Foreign Service Journal, September 2023

- “In Their Own Words: An Interview with Four Foreign Service Authors” by David K. Wessel, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2024