Holding History in the Vatican’s Secret Archives

Reflections

BY VINCENT CHIARELLO

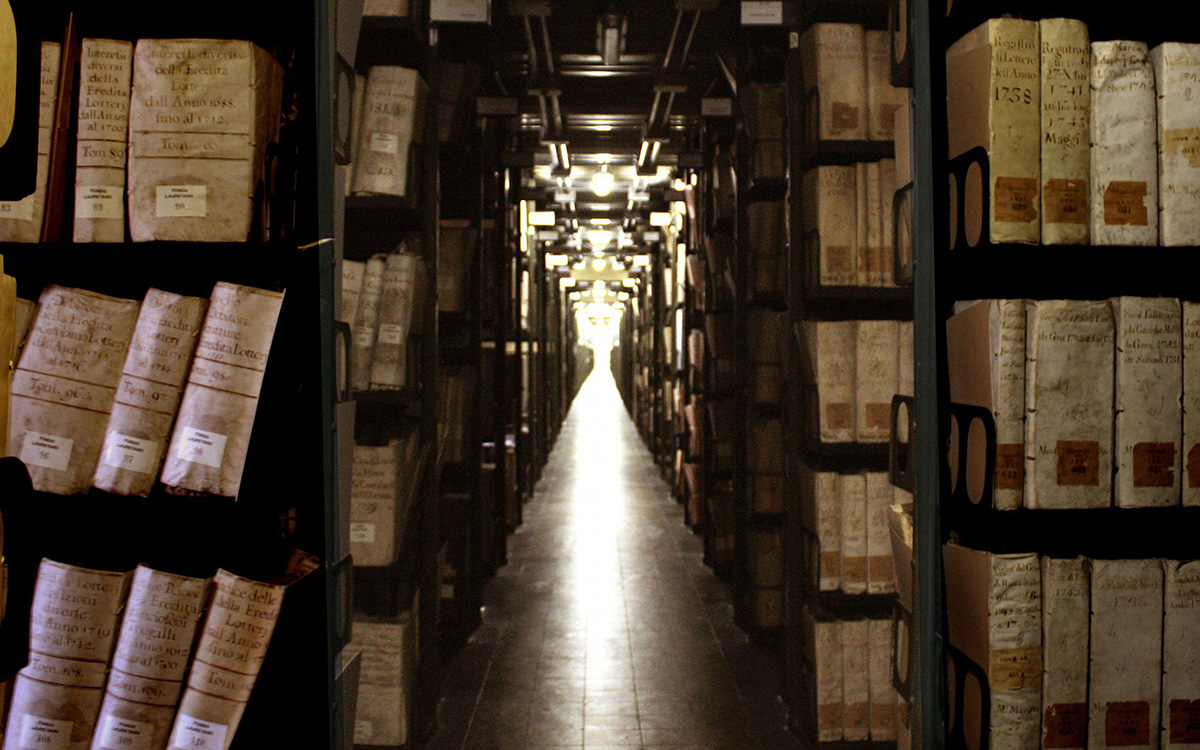

A stretch of hallway in the Vatican Secret Archives circa 2012.

Abaca Press / Alamy

In January 1993, shortly after returning to Washington from an assignment at the U.S. Embassy to The Holy See, I was invited to attend the opening of the exhibit, “Great Libraries of the World,” at the Library of Congress. The Vatican Library, first established in 1485 and the oldest in the world, was the first to be so honored. The invitation was extended by Rev. Leonard Boyle, O.P., then prefect (head) at the Vatican Library, whom I had met during my assignment.

After I received my diplomatic tessera (credentials) from the Vatican in 1990, one of my first visits was to the library, where I met Father Boyle, a highly respected Oxford-trained paleographist, or student of manuscripts. He described to me the role the U.S. had played in the reorganization of the Vatican Library, which includes the “Secret Archives.”

In 1928 the Carnegie Endowment had sent a team of U.S. cataloging experts, along with the librarian of the American Academy in Rome, to provide guidance to the Vatican Library’s staff. That staff included a future prime minister of Italy, Alcide De Gaspari.

A decade later, during the library’s renovation, 14 miles of steel shelving from the Snead Shelving Company of New Jersey were installed throughout the library. Given the roles of the Carnegie Endowment and Snead Shelving, Fr. Boyle acknowledged the U.S. had a part to play in the development of the world’s oldest library.

After discussing the problems scholars faced in using Vatican Library resources, Fr. Boyle asked me, “Have you been to the Secret Archives?” I had not, but Fr. Boyle offered his assistance in setting up an appointment with Fr. Josef Metzler, then prefect of the Secret Archives. For understandable reasons, this visit would remain indelibly etched in my mind.

Fr. Metzler, a librarian by training who had served on various pontifical committees regarding the storage and classification of the artistic and cultural patrimony of the Vatican, began our conversation in his office by asking what I knew of the Secret Archives. My answer: “Not much.”

Atop the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, one gets a bird’s-eye view of the Vatican City in Rome.

Diliff / Wikimedia

The term “Secret Archives” is misleading, he told me, and the word “Private” more accurate because scholars with genuine research projects are able to use the archives. Fr. Metzler described the origins of the archives, which began in the second century A.D. and were originally stored under the title “the Holy Scrolls” of the Church.

Each pope was, by custom, allowed to keep documents of his pontificate in his residence. The major problem with this form of storage was that these paper documents were fragile, and when a transfer took place, multiple pages were destroyed. To prevent that from happening, the papacy began to use vellum, whose shelf life, as I was to find out, is very long.

The Vatican’s Secret Archives were first collected and stored in some systematic order in Rome’s Castel Sant’Angelo (Hadrian’s Tomb), but in 1611-1614 they were moved to the Vatican. Napoleon ordered the confiscation of the archives in 1810, and they were sent to Paris. They were returned to Rome five years later, although, according to the Pontifical Annual, “with many lost.”

In 1880 the archives were opened by papal decree to allow “the free consultation of scholars,” although Vatican Library officials typically offered little more than superficial assistance. This situation dramatically improved under Fr. Boyle’s recent leadership.

After this review of the origins and development of the Vatican’s Secret Archives, Fr. Metzler asked me: “Would you like to see something interesting?”

I accompanied him to an elevator that took us three levels below the ground floor of the library. When the door opened, we began to walk through what had originally served as the burial ground for Christians, or catacombs in ancient Rome, but was now the repository of the Secret Archives.

As we walked, I observed the corridor, which was about 10 feet wide and bracketed by steel shelves. On these shelves were numbered olive-green-colored loose-leaf binders arranged by the years of pontificates. I cannot recall how long we walked, but what I do remember was asking Fr. Metzler if we were now in Sweden.

Shortly thereafter, Fr. Metzler said, “Ecco” (We’re here), took a step stool, went to the highest shelf, and brought down a binder.

As he opened this particular binder, Fr. Metzler asked me to stand at his side. As he turned the pages, I noticed the documents were made of vellum, not paper, and were encased in a transparent plastic cover for protection. He then took out one page, handed it to me, and asked if I knew what I was holding.

The writing on the document was in legible, understandable Italian, and the quantity and description of the number of items indicated it was a bill. That was even more certain because at the right side of the document were the letters “FL.” Florins were the unit of monetary exchange in the Papal States during the Renaissance.

I responded that it was a bill, to which the prefect quickly retorted, “But whose?” I turned the page over, and about halfway down were the very large letters “MB.”

“Buonarotti,” I said. Fr. Metzler nodded.

What I was holding in my hand was the original bill that Michelangelo Buonarotti had sent to the Vatican to pay for the material he would use to paint the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling. Several weeks later, I would be able to see firsthand what that bill’s contents had achieved when I stood on the scaffolding of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel during its final stages of restoration.

Looking back, my years in being posted to six different embassies were unforgettable—not only because I was able to visit the Vatican’s Secret Archives or touch the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, but also because it allowed me to meet men like George Kennan, an icon in the Foreign Service, perhaps a reflection for another time.

The words of the legendary baseball player, Lou Gehrig, come to mind: “I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth,” he said. To that I would simply respond, “So do I.”

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.