When Terror Strikes Home: Covering Our Children While Protecting All Americans

Foreign Service crisis management can involve your own family. A career FSO and ambassador recalls his harrowing experience in Cambodia, and the lessons learned.

BY KENNETH M. QUINN

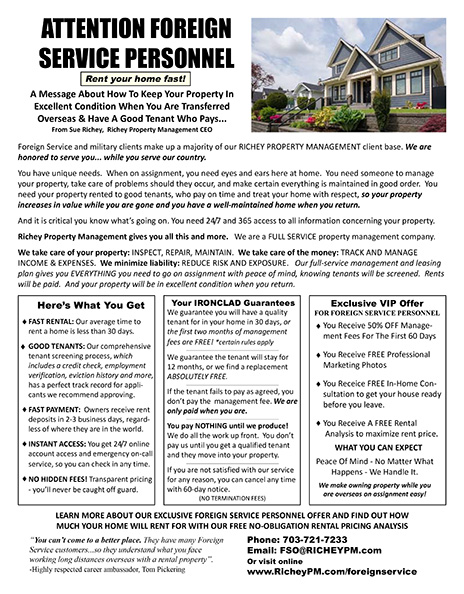

In 1995, at the ceremony where he received the Arnold Raphel Award, Ambassador Kenneth Quinn poses with his wife, Le Son, and two of their children, Kelly and Shandon. (Their son Davin was at college and thus not able to attend the ceremony.) Shortly after, they traveled to Cambodia for his posting.

Courtesy of Ken Quinn

Of all the horrible images and tragic stories to emerge in 2022, the combat-style attack on Fourth of July parade attendees in Highland Park, Illinois, stands out for me. The assailant in this merciless act aimed to exact lethal casualties, stirring memories of what I had witnessed as a Foreign Service officer on the battlefield in Vietnam in the late 1960s. But it was the picture of little 2-year-old Aiden McCarthy wandering about in bloodied clothes, saved from death by being covered by his father’s body, that prompted a particularly vivid recollection from my Foreign Service career: In 1997, in Cambodia, my wife and I had a very similar terror-filled experience, covering our children.

A Meeting with Terror in Phnom Penh

It took place shortly before the Fourth of July in 1997, when I was serving as American ambassador in Cambodia. With the end of the school year in the U.S., my wife, Le Son, and our three teen and tween children had just arrived in Phnom Penh so we could spend the summer months together.

After a long period of violence, Cambodia now seemed to be at peace. The Khmer people, who had suffered so incomparably under the genocidal Khmer Rouge (almost 2 million of the total population of 7 million had perished under the draconian rule of Pol Pot) were slowly recovering under a United Nations–supported peace process and a new democratically elected coalition government, all put in place with critical U.S. involvement across the George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton administrations. As deputy assistant secretary in State’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, I had bridged those two political leaderships and was now in Cambodia to carry forward the support of the new government.

That night, however, the cease-fire that had provided a several years’ respite from the two-decade-long civil war, abruptly ended as fighting broke out between the two main political factions that militarily occupied villas on Norodom Boulevard in the heart of the capital city. Our ambassadorial residence was right next to one of those heavily fortified villas, with sandbagged fighting positions manned by armed troops right outside the walls of our residence.

The first salvo was the firing of a rocket that, without any warning, struck our residence, blowing in the windows and narrowly missing the room where we were all gathered to watch a movie. Had the rocket struck just a few feet differently in either direction, it would likely have wounded or killed us all.

Now, even 25 years later, my clear recollection is of lying there and praying, begging God to allow any bullets that came into our home to kill me and not our children.

This explosion, which shook the house and shattered the windows, was instantaneously followed by an outbreak of automatic weapons fire surrounding the house. Suddenly, our residence was engulfed in an intense firefight. The incessant gunshots from just outside our walls were so loud and numerous that the sound permeated the entire house, bringing terror and the threat of imminent death directly into the family room.

In those few seconds I acted on instinct, following a deeply embedded parental impulse. Pulling our three children to the floor, my wife and I desperately covered them with our bodies. Now, even 25 years later, my clear recollection is of lying there and praying, as I had never prayed before, begging God to allow any bullets that came into our home to kill me and not our children. It was the moment when I fully understood just how much I loved my children, how absolutely ready I was to give my life to save theirs. I have to believe that Kevin and Irina McCarthy made that same desperate supplication right before they died in Highland Park.

Miraculously, none of us were harmed by that initial fusillade. As all this was transpiring, I almost simultaneously followed another instinct, this one inculcated by my experiences as deputy chief of mission in the Philippines during coup attempts against the government of President Corazon Aquino: the need to address the security of all Americans in the country.

Terror as an Occupational Hazard

Physically covering our children while lying on the floor, I reached up to grab my radio that linked me to my senior embassy staff. With it, I issued the order to activate our consular warden network to alert all American citizens to urgently take shelter and avoid moving about the city. Keeping the radio in place near one ear with one hand, I used my other hand to dial the phone number of the State Department’s 24-hour Operation Center (which I had memorized) to report our precarious security situation. Our perilous situation was further exacerbated by the absence of any Marine Security Guards; we were literally a Benghazi-like embassy.

As the shooting began to subside, we moved the children to a more secure location inside the house, where any bullet would have to go through several walls to reach them. I then turned to the urgent need to get the two Cambodian factions to stop shooting. No one in the Cambodian government was answering their phones, so I had to cross Norodom Boulevard and get to the home of the interior minister. Waiting for a pause in the gunfire, I raced across the street and banged on the front door. I exhorted the minister, whose reception area looked like a war command center, to try to connect with his counterpart and get their troops to stop shooting. While I was there, he got through; and soon they agreed to halt the hostilities and exchange a liaison person to facilitate communications.

Our perilous situation was further exacerbated by the absence of any Marine Security Guards; we were literally a Benghazi-like embassy.

Over the next days and weeks, however, mutual suspicion and antagonism grew, and the threat of renewed warfare persisted. When the situation completely broke down and open warfare was again waged in the center of the capital city, our small embassy earned special recognition for our actions.

One of our first steps was providing interim protective arrangements for all Americans in the city by renting the ballroom of the Cambodiana Hotel. Remembering the lesson I learned in Manila, that we had to have such a place during the fighting, I beat the French ambassador in leasing the space in the most secure area in town. It served as a safe haven for more than a thousand of our citizens along with embassy families and nonessential staff while we worked to successfully evacuate almost all of them from the country.

In the absence of virtually all the local hotel staff, who deserted as the fighting intensified, my wife, Le Son, and our 12-year-old daughter, Kelly, worked in the kitchen helping prepare and serve food for their fellow American citizens. They were evacuated to Vietnam with the last tranche of American citizens. During the days of July 5 and 6, the situation in the city became increasingly untenable, as marauding military units roamed about, and artillery shells struck randomly, including near the embassy, badly shaking the structure every time. Having sent all but the most essential personnel to the relative safety of the Cambodiana Hotel, we were down to a skeleton staff. I had given the order to destroy all of our classified paper records and was preparing to break up the secret codes in our communications room, the last step before abandoning the embassy completely.

A Diplomat’s Job

In 1998, at the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh, Ambassador Kenneth Quinn (at right) meets with King Norodom Sihanouk about steps to take to encourage some candidates from the Royalist political party to return to Cambodia and contest the national election, an approach that was successful.

Courtesy of Ken Quinn

It was then that two phone calls came to me. One was about a group of Mormon missionaries who were trapped amid the fighting going on near the airport. They had no way out and were desperate for evacuation.

No sooner had I hung up when another call came, from a Cambodian American who had been serving as a minister in the government but was now caught up in the internecine warfare. He was trapped in a construction project somewhere near the airport but would not disclose his exact location for fear that the phone call was being monitored, and he would be tracked down and killed.

He tearfully asked me to call his wife in Bangkok and say goodbye for him. As the battery on his cell phone was running down, we were suddenly disconnected. Not having any U.S. Marines or any other armed security force at the embassy, I thought there was only one thing I could do. Grabbing one embassy officer to go with me, we took my Chevrolet Impala, which served as the ambassador’s “limo” and, unfurling the American flag on the front fender, drove toward the airport where black smoke rose and the sound of automatic weapons filled the air.

Driving through roadblocks and around troop formations, we arrived at the Mormon mission where the group leader rushed out and told me he had never been so glad to see the American flag in his life. With their safety assured, I continued driving toward the area where I believed the Cambodian American government official was hiding. Weaving around tanks and past advancing troops with the sound of gunshots resonating, I kept calling his number on my cell phone, leaving messages urging him to run out and jump in the car. But he never answered, and I could not tell if he had even been able to hear my messages. Eventually, we gave up and turned back to the embassy.

A few hours later, I went over to the hotel where hundreds of Americans were gathering. As I walked into the lobby with several of my interagency staff, many of our fellow citizens began clapping in appreciation for all that we had done to keep them safe. While I felt good that so many Americans had been able to be kept safe from the fighting, I still was despondent that I had not been able to help that one political leader.

Remembering the lesson I learned in Manila, that we had to have such a place during the fighting, I beat the French ambassador in leasing the space in the most secure area in town.

But then I looked up, and there he was—a big, burly Cambodian man walking down the corridor toward me. I rushed up to him expressing amazement that he was alive and safe.

“I came looking for you and was afraid that you had been killed,” I said.

“I know you did,” he replied. “I saw you, but I didn’t dare run out.”

And then, contrary to all usual interpersonal aloofness that characterizes cultures in Southeast Asia, he stepped forward and threw his arms around me. Hugging me, he said something that I will never forget: “Now I know what it means to be an American.”

Lessons Learned

Eventually, we evacuated more than 1,000 Americans from Cambodia and had the satisfaction of knowing that we did not have one citizen hurt, wounded, or killed. A few months later, after the fighting had subsided and Americans could return to the country, a man who said he was from Salt Lake City came to the embassy and asked to see me. When I expressed puzzlement about why he was there, he explained that he had been sent by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to thank me for “your heroic efforts” to ensure that the Mormon missionaries in Cambodia were safe.

I expressed appreciation for his message but explained that it was just part of the job being an American diplomat. We are employed to advance and protect America’s interests and its citizens around the world, often in difficult and dangerous circumstances. Our career grants us a front-row seat to the making of history, and it also exposes us to potentially life-threatening challenges. Indeed, I was shot at, wounded, or under death threat in every foreign assignment I had during my three-decade Foreign Service career.

We learned another valuable lesson from our experience in Phnom Penh: When a violent political crisis is over, it really isn’t over. Two years later, in 1999, our now high-school-age daughter and I arrived in Des Moines, Iowa. Having retired from my 32-year diplomatic career, I was about to take up leadership of the World Food Prize Foundation. Kelly was preparing to start training with her high school swim team.

One evening right around July 4, as she and I were sitting at home, we were suddenly transported back two years by a rat-a-tat-tat-tat sound that almost perfectly replicated those automatic weapons firing on that night in Phnom Penh. As we both instinctively dove to the floor, we locked eyes, and I said: “I think it’s firecrackers going off for the Fourth of July …”

On every future Fourth, when they hear the sound of firecrackers going off, I imagine everyone caught in that Highland Park mass shooting will be painfully transported back to those terror-filled moments they experienced in 2022.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Cambodia: July 1997: Shock and Aftermath,” Human Rights Watch, July 2007

- ADST Foreign Affairs Oral History Project: Interview with Ambassador Kenneth M. Quinn by Charles Stuart Kennedy, August 2013

- “Viet Cong Attack on Embassy Saigon, 1968” by Allan Wendt, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2015

- “A Day of Terror: From the FSJ Archive,” July-August 2018

- “Diplomacy Can Save the Day” by George Lambrakis, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2019