When Lightning Struck Twice: How AFSA’s “Young Turks” Launched the Union

Once a polite diplomats’ society, AFSA is now a financially and politically strong union and a player on the wider stage—with the administration, Congress, and the American public.

BY THOMAS BOYATT

The “Bray Board,” headed by reformer Charles W. Bray III, steered AFSA from January through December 1970. The board prepared the way for AFSA’s victories in representation elections and negotiations with management. Pictured here, from left: George B. Lambrakis, Alan Carter, Erland Heginbotham, Barbara Good, Richard T. Davies III, Bray, William G. Bradford, Princeton Lyman, William Harrop, and Robert Nevitt.

FSJ Digital Archive

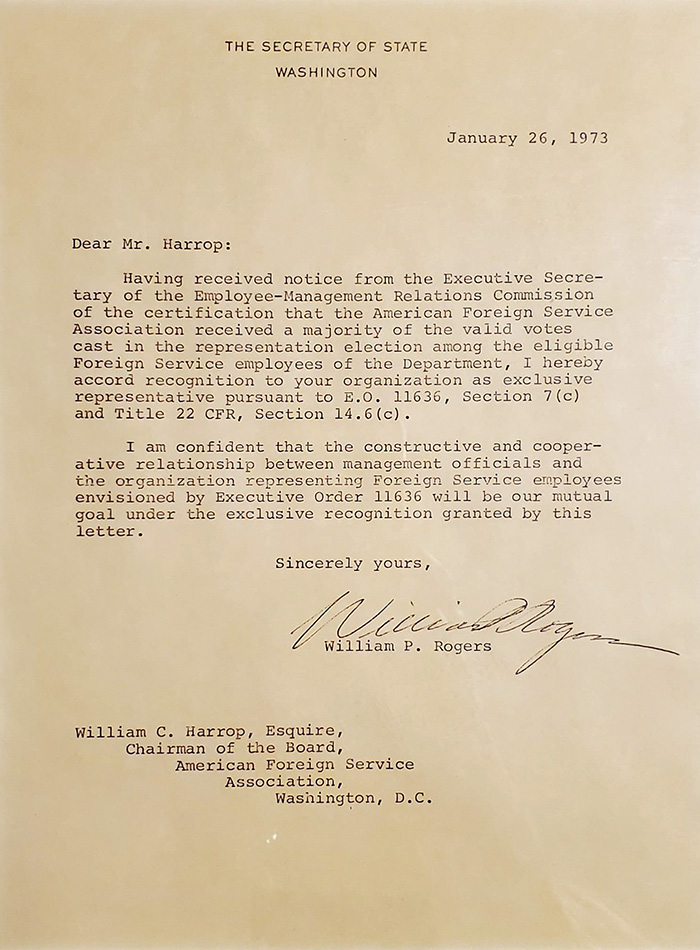

Letter from Secretary of State William P. Rogers to AFSA Board Chair William C. Harrop affirming AFSA’s recognition as the exclusive representative for the State Department’s Foreign Service.

AFSA

Next year, in 2024, we celebrate AFSA’s centennial. For the first half of its century, AFSA was a small professional association with little income, a tiny staff, and almost no influence beyond its membership of American diplomats.

Then, in the late 1960s, lightning struck. Twice.

First, a group of junior and middle-grade Foreign Service officers (FSOs) decided to contest AFSA’s 1967 leadership elections. The goals of these “Young Turks” (as we came to be called) were to use AFSA as a vehicle to:

- make the Foreign Service (FS) more professionally effective by giving AFSA a voice in the functioning of the personnel system;

- create safeguards against management abuse; and

- build AFSA’s political and financial strength to the point that we could defend the Foreign Service as an institution and individual Foreign Service personnel against external political attacks.

We had seen that from 1948 to 1952, President Harry S Truman and Secretary of State Dean Acheson did not protect the Service and FSOs from attacks by the Democrat-controlled House Un-American Activities Committee. Likewise, neither President Dwight Eisenhower nor Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had protected us from the depredations of Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis.) from 1952 to 1956. The lesson was clear: In Washington, you must be able to defend yourself.

Second, in 1969 President Richard Nixon unexpectedly decreed, in Executive Order 11491, that there should be unions in the federal sector. Suddenly, there was a potential pathway for AFSA to secure and build political and financial power on a presidentially sanctioned basis as a union. It was the opportunity of a lifetime; but, of course, not everybody saw it that way. A period of disagreement and debate ensued, both within AFSA and within the Foreign Service generally.

We all know how the saga ends. AFSA did become a union. We celebrate this year the glorious golden anniversary of AFSA’s election victories to become the union of all Foreign Service personnel. Indeed, in its half century, AFSA the union has put AFSA the professional association cum union on Washington’s power map. This happy outcome, however, was by no means a foregone conclusion.

The years following Nixon’s 1969 pronouncement were a time of strife and struggle. There were elections to be won and momentous negotiations to maximize the potential fruits of victory; and the costs of failure were correspondingly enormous. AFSA President Eric Rubin refers to this era as AFSA’s “heroic age.” Here is that story from the viewpoint of a combatant.

Three Elections and an Existential Negotiation

Tom Boyatt celebrates a union election victory in Washington, D.C., in the mid-1970s.

Courtesy of Tom Boyatt

The AFSA Election of 1967. In the winter of 1966, the future Young Turks began to meet in Charlie Bray’s basement to discuss how to improve the Foreign Service. We agreed on only two things: We had to have an institutional platform to reform the FS, and AFSA was the ideal organization for that purpose. Accordingly, Bray recruited Lannon Walker, and they organized a reform slate to contest every board and officer position in AFSA’s 1967 election. The Young Turks won every seat. At that point we faced the reality that discussing reform is much easier than making it happen. There were consultations with management over the next two years, but no durable results.

The AFSA Election of 1969. With Walker posted overseas, Bray organized the second Young Turk slate, which swept all positions. Later, in 1969, the Nixon executive order raised the union issue, and that became the overriding focus for the Bray Board. From this point on, the protagonists were:

• The American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) and the Junior Foreign Service Officers Club (JFSOC) wanted a single system for all government employees under E.O. 11491, the exclusion of all “managers” broadly defined from the union, and a three-year contract covering employee working conditions;

• The Young Turks on the Bray Board and the soon-to-be-formed Harrop Board strongly favored a union system, but one that was independent of the Civil Service and one that recognized the unique aspects of the Foreign Service. We also favored negotiation of personnel policy agencywide and a narrow definition of management official that would put the vast majority of FSOs in the bargaining unit; and,

• State Department management’s overriding goal was to protect the special status conferred on the Secretary of State and the Foreign Service Director General by the Rogers Act of 1924. Interestingly, management itself was divided into two groups. Many senior officers—Bill Macomber, Nat Davis, Larry Eagleburger come immediately to mind—were in varying degrees sympathetic to the Young Turks’ objectives. For them, love of the Foreign Service and its people trumped all else. Other managers, sovereign in their areas of expertise, had great difficulty accepting that they would have to negotiate with middle-grade political and economic officers (the AFSA leadership) with any disagreements going to third-party adjudicators.

While the above groups were forming and dissolving coalitions on the various questions that arose, AFSA President Bray had the challenge of discovering whether AFSA and the Foreign Service actually wanted a union. Bray held a worldwide referendum on the issue of whether AFSA should form a union. A statistically overwhelming 2,241 members participated, 25 percent of the total membership, with 85 percent favoring the proposal. Bray also proposed a formal board vote on participating in the upcoming union election. The proposal was strongly, but not unanimously, approved. Bray began meetings with management on the form of the new employee-management structure, but these discussions were overtaken by two developments that unfolded concurrently—namely, the 1971 AFSA election and a negotiation chaired by the Department of Labor on the form of our employee-management system to be detailed/codified in a separate Foreign Service executive order.

The Existential Negotiation over Executive Order 11636. In October 1969, President Nixon issued E.O. 11491 establishing an employee-management relations system for the federal government service, including the Foreign Service. Secretary ARCHIVEof State William Rogers objected strongly to an FS employee–management system controlled by the Secretary of Labor rather than himself.

This disagreement reportedly went to the president, who decided in favor of Secretary Rogers. The Foreign Service would have its own employee-management system. However, the Labor Department was directed to conduct a negotiation among the parties (AFSA, JFSOC, AFGE, and State management) to produce an agreed executive order distinct and different from E.O. 11491. An administrative judge from the Labor Department was put in charge of the negotiations. The Macomber-Bray discussions were now moot.

In the winter of 1966, the future Young Turks began to meet in Charlie Bray’s basement to discuss how to improve the Foreign Service.

The E.O. 11636 talks lasted for several months. AFGE and JFSOC argued to bring the Foreign Service under E.O. 11491. AFSA and State management argued for a separate E.O. 11636 recognizing the unique personnel system and working conditions of the Service. Management’s overwhelming goal was a separate system, as made clear by Secretary Rogers. To achieve this, management needed AFSA. This leverage encouraged management to follow our lead on the more “technical” issues, as long as we supported a separate system. In the end, the provisions of E.O. 11636 were much more union-friendly than E.O. 11491, which applied to the Civil Service. Specifically:

- AFSA was a single bargaining unit for all FS personnel worldwide; AFGE bargaining units, by contrast, were mini sections of small units throughout the country.

- AFSA negotiated “personnel policies and procedures” on an agencywide basis; AFGE negotiated working conditions in each of thousands of bargaining units.

- AFSA only excluded personnel in specific management jobs, while all others were in the unit; AFGE, by contrast, excluded every manager broadly defined from the unit.

- AFSA’s negotiations were “rolling.” Either party could raise any issue at any time. By contrast, AFGE negotiated all issues during a fixed period every three years into a single contract.

- AFSA had input into the selection of members of the adjudicatory bodies; AFGE had no such inputs.

The provisions of E.O. 11636 made AFSA a major player in determining the personnel system and, therefore, the quality of U.S. diplomacy, while AFGE dealt with small problems in hundreds of small units. AFSA’s mutually reinforcing dimensions of professional association and union provided a unique basis for AFSA to become a major force in the Foreign Service world. Our duality continues to reinforce AFSA’s strength. E.O. 11636 was clearly much more favorable to AFSA than the Civil Service system.

The AFSA Election of 1971. The intensity of the E.O. 11636 negotiations did not reduce AFSA’s internal political differences. The contenders continued to, well, contend.

Bill Harrop brought together holdovers from the previous Governing Board including F. Allen “Tex” Harris, himself, and others. He also recruited a more aggressive cadre of candidates including myself, Hank Cohen, and Barbara Good, who favored E.O. 11636, recognizing the importance of an employee-management system separate from the Civil Service and the favorable terms and conditions emerging from the E.O. 11636 negotiations. We called ourselves the “Participation Slate.” We were a coalition of political and economic officers from the regional bureaus, as well as secretaries, communicators, and representatives from the U.S. Information Agency and USAID.

In strong opposition was the “Members’ Interest Slate,” whose core group was the leadership of JFSOC. Although supporting a union in principle, they attacked from the left, strongly criticizing E.O. 11636 and the Participation Slate for its alleged sellout by accepting that E.O. They opposed the concept of AFSA as both a professional organization and a union, and generally projected a junior officer image although their slate was diversified.

For our part, the Participation Slate argued that AFSA could become an effective union while maintaining its status as a first-rate professional association. We supported E.O. 11636 because it emphasized the uniqueness and independence of the Foreign Service while providing a much stronger union role than E.O. 11491. Our goal was to reach out from the center of the AFSA polity to both right and left.

The open meeting debates were sharp, with both ideological and generational overtones. Each side worked the halls of State and sought to contact friends and sympathizers at posts abroad. When the votes were counted, the Participation Slate had swept all 11 Governing Board seats. The Members’ Interest Slate fought well, their best vote-getter coming within 60 votes of our lowest scorer. But the Participation Slate won a clear mandate to lead AFSA into the world of unionism. Then it remained to be seen whether AFSA could defeat mighty AFGE to lead the Foreign Service into this new world.

The Showdown: AFSA versus AFGE

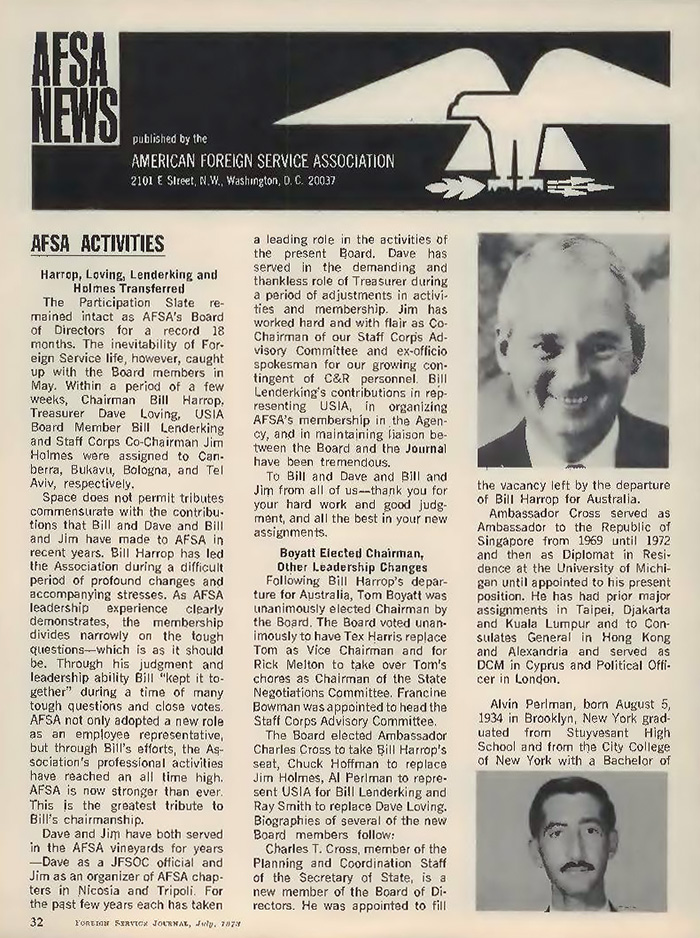

Announcement of leadership turnover at AFSA in the July 1973 Foreign Service Journal AFSA News section.

FSJ Digital Archive

E.O. 11636 and AFSA’s internal election were both completed at the end of 1971. The Labor Department then established the “Employee Management Relations Committee” (EMRC) to oversee elections in the foreign affairs agencies (State, USAID, and USIA) under the aegis of E.O. 11636. An administrative law judge was assigned the task of managing that election.

On its face, the election was a David-versus-Goliath situation. AFGE already represented many in the Civil Service; it had millions of dollars to spend on campaigning; it could field scores of lawyers; and it was an affiliate of the all-powerful AFL-CIO. AFSA, on the other hand, did not formally represent anybody; we were financially insolvent (in fact, seriously in debt given the recent purchase of the headquarters building); we had no lawyers on staff (oh blissful time); and we were without institutional allies. But we had one huge advantage: We knew and loved the Foreign Service and its people, and that showed.

At its early March 1972 organizational meeting, the new AFSA board elected Bill Harrop as chairman and myself as vice chair, along with other officers and committee chairs. I was named “participation coordinator” with responsibility for obtaining a “showing of interest” to start the election process. The “showing” consisted of signed cards from at least 25 percent of the bargaining unit (2,000 cards from State, fewer from USIA and USAID) calling for elections.

I immediately recruited fellow Young Turks Rick Melton, Jack Binns, David Ransom, and other stalwarts to go door-to-door in State’s halls and by diplomatic pouch to our friends overseas collecting signed cards. By the end of April, we had 1,000 signed “showings” from State alone. By May, cards were flowing in from overseas, and we exceeded the minimum necessary 2,000 cards, a number that was doubled by early June.

Our Participation Committee became the Election Committee. We petitioned the EMRC judge to hold representation elections in State, USAID, and USIA. At this juncture, AFGE, seeing our strength in gathering the showing of interest cards, realized they could not defeat AFSA in open elections. Calling on their platoons of lawyers, AFGE sought every delay possible. They alleged the showing of interest was void because Bill Harrop was a member of the Policy Planning Council and that Hank Cohen and I were similarly tainted because we had served on promotion boards. Eventually, the EMRC dismissed these and other stalling ploys and summoned AFSA and AFGE (who had filed 400 showing cards that allowed them to get on the ballot) to a pre-election conference in August.

Bray held a worldwide referendum on the issue of whether AFSA should form a union.

On Sept. 26, 1972, the EMRC judge directed that a worldwide union election for Foreign Service employees at State, USIA, and USAID be held during a 52-day period beginning Oct. 10, 1972. AFSA proposed programs strengthening an independent Foreign Service and negotiations with management on personnel policies and procedures. But our main point was that we were, above all, members of the Foreign Service. To quote our final appeal: “Remember, AFSA belongs to us. AFSA has more active committee members working for you than AFGE has Foreign Service members. AFSA can take positions without checking with the AFL-CIO … or with AFGE headquarters (to clear the impact on the Civil Service). LET’S. DO. OUR OWN. THING.”

State ballots were counted on Dec. 4, 1972. AFSA was the overwhelming victor with a 75 percent majority. At USIA, certification of our strong victory was delayed by AFGE’s final, futile, protests. At USAID, management in extreme denial refused to hold elections. That silliness was overcome, elections were held, and AFSA won 80 percent of the vote. By the end of March 1973, AFSA Chairman Bill Harrop had received certification letters from the Secretary and the heads of the other foreign affairs agencies. AFSA now had the power and responsibility to negotiate personnel policies in the foreign affairs agencies and to defend and speak for their employees.

Bringing Management to the Table: The AFSA Election of 1973

By late summer of 1972, it had been clear that AFSA would defeat AFGE in the October-November representation elections at State, USAID, and USIA. Accordingly, we organized a Negotiations Committee to have proposals ready to table with management as soon as we were certified. Our team of Bob Pelletreau, Rick Melton, Tex Harris, Jack Miklos, Bruce Hirshorn, Jim Holmes, Barbara Good, and Hank Cohen resembled the 1927 Yankees in firepower. In the days and weeks following AFSA’s certification, we tabled more than 50 proposals from checkoff of dues (management collects and remits to AFSA) to kindergarten allowances and promotion precepts. Management was not only in denial; it was neither organized nor staffed to meet our “shock and awe” proposal blitz. A period of paralysis ensued, but we were clearly defining the agenda.

At the same time, Foreign Service realities caught up with the AFSA board. That spring and summer, Chairman Bill Harrop, Treasurer David Loving, USIA Representative Bill Lenderking, and Staff Corps Co-Chair Jim Holmes were transferred to Canberra, Bukavu, Bologna, and Tel Aviv, respectively, as reported in the July 1973 FSJ. Tom Boyatt, Tex Harris, and Rick Melton were elected AFSA chair, vice chair, and chair of the Negotiations Committee. Further, Tex Harris, who had been on leave without pay serving full time as AFSA’s counselor, returned to the Foreign Service. Tex continued to push for a legislated grievance system for the Foreign Service. He succeeded with the passage of the “Bayh Bill” (S.782, a bill to provide for the establishment of a Foreign Service grievance system), which went into effect in 1976. Tex was replaced by Rick Williamson, who made enormous contributions during his tenure. Our season of change was capped in September when Henry Kissinger replaced William Rogers as Secretary of State.

I immediately sought a meeting with Henry Kissinger, which, to our surprise, was quickly arranged. On Sept. 6, Tex Harris, Hank Cohen, and I trooped into Kissinger’s White House office. [Kissinger, then National Security Adviser, was to also become Secretary of State Sept. 23.] For 45 minutes, we outlined our objectives. I closed by informing the Secretary-designate that I would testify against unqualified ambassadorial nominees if so directed by the AFSA board. Kissinger closed by reminding me that he could “always send you to Chad,” to the hilarity of all present, save myself. Our unanimous impression was that Kissinger realized we were beyond his diktat. He appeared inclined to accommodate many of our goals in exchange for “peace and quiet.”

Suddenly, there was a potential pathway for AFSA to secure and build political and financial power on a presidentially sanctioned basis as a union.

The news of the AFSA leadership’s meeting with Kissinger swept through the department like a prairie fire. Most senior officers had not met with the incoming Secretary, and our meeting sent them a message. Soon the negotiating logjam was broken. In late 1973, the incumbent AFSA board was overwhelmingly reelected as the “Achievement Slate” to serve until 1975. By the end of the term of the last of the Young Turk boards, there was a dramatic increase in agreements with State (most notably) and the other foreign affairs agencies; new initiatives were undertaken, such as the hiring of AFSA’s first staff lawyer, Cathy Waelder; representations to Congress were put in place; and the employee-management system had been well and truly launched.

Of course, AFSA history did not end in 1975. For five decades, generations of AFSA presidents, officers, and boards have taken AFSA up the growth curve and brought us to our current eminence. When we defeated AFGE, our budget was under $200,000; today the budget is nearly $6 million. Then we were in debt; today we have a “war chest” of more than $3 million. Today our legal staff alone is larger than the entire staff then. When we started there were no employee-management or grievance systems, and we did not represent anybody; today both systems are enshrined in the Foreign Service Act of 1980, and we represent all Foreign Service personnel of the foreign affairs agencies. Indeed, we have much to celebrate on this, our golden 50th.

Today and Tomorrow

Recently, AFSA demonstrated political power at the outer edge of the hopes and dreams of the “Young Turks” 50 years ago. In 2017 President Donald Trump proposed a budget that reduced international affairs expenditures (the 150 account) by 37 percent. AFSA President Barbara Stephenson and her board and staff immediately engaged and encouraged an informal caucus composed of all Senate Democrats and about 12 national security Republicans, who worked to defeat the proposed drastic cuts. In the end, the caucus defeated the cuts and engineered a slight increase in the 150 account. The same process with the same result occurred with Trump’s 2018, 2019, and 2020 budgets. It was a clear demonstration that AFSA has the means and will to defend the Foreign Service as an institution.

In 2020 President Trump’s allies began a smear campaign against career FSO Marie Yovanovitch, our ambassador in Kyiv, because she would not participate in schemes to involve the Ukrainian government in anti-Biden activities in the middle of the presidential campaign. She was recalled to Washington and summoned to testify in the Trump impeachment trials and hearings. The smear campaign continued. AFSA President Eric Rubin and his team came out punching. They immediately reactivated the AFSA Legal Defense Fund for the FSOs under attack and raised $750,000 in a very short time. Our media and congressional networks were deluged with our narrative that FSOs swear to “defend the Constitution of the United States,” not a particular administration or president. Marie Yovanovitch and her colleagues became and remain heroes. It was another clear demonstration that AFSA has the means and will to defend individual FSOs—promises made by the Young Turks and redeemed by our successors.

Looking back 50 years, I am gratified, even astonished, that we achieved so much in such a short time. I am also terrified by what I now realize but had no clue about at the time—namely, with one mistake, one lost election, or a botched negotiation over E.O. 11636, today’s celebrations would not exist.

Looking forward, I am delighted that AFSA has the financial and political power to defend the Foreign Service and its people, but fear also lurks. Will future leaders have the wisdom to understand AFSA’s capabilities and the courage to use the means available in defense of the Foreign Service as an institution and its people? I am hopeful. What is certain is that hard tests lie ahead. May God be with you, as certainly was the case with us at the rebirth of our unique association 50 years ago.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Swan Songs and Journalistic Integrity” by Thomas Boyatt, The Foreign Service Journal, April 1998

- “AFSA Becomes a Union: 4 Battles” by Thomas Boyatt, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2003

- AFSA History Timeline, May 2014

- “Role Models: Lessons for Today from AFSA’s Past” by Harry Kopp, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2019