The Journal in Transition—The 1980s

As the Cold War lurched to an end and the Foreign Service Act of 1980 came into force, new challenges emerged and the Journal’s profile got a refreshing boost.

BY STEPHEN R. DUJACK

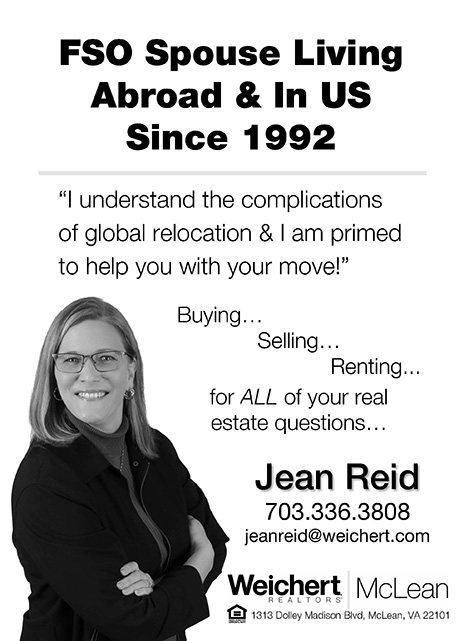

The July-August 1981 FSJ debuted the new approach to covers with this iconic NASA photo of the Earth as seen from the moon.

My tenure at AFSA started in 1981, just six weeks after the Foreign Service hostages held in Iran returned home, and ended a few months before the collapse of communism and ultimate dissolution of the Soviet Union. So I barely missed the two most important events affecting American foreign relations in that decade. But my seven years at the helm of The Foreign Service Journal occurred during the last gasps of the Cold War, what New York Times columnist Ross Douthat called “the Armageddon-haunted 1980s.” The face-off in Europe threatened to push the world to the nuclear brink. Meanwhile, the Middle East was an ongoing powder keg. And North-South issues were emerging to crowd ever-worsening East-West issues on the world stage.

Not coincidentally, it was a period of huge challenges to the diplomatic profession and to foreign affairs professionals personally.

For the former, there were antagonists like Senator Jesse Helms (R-N.C.), a ranking member of the Foreign Relations Committee and later its chair. Helms was always a thorn in the side of the State Department as he sought to impose his worldview on diplomatic officials and, with his “mini-State” on his staff, the foreign policy they carried out. At the same time, President Ronald Reagan was naming an alarming number of political appointees to ambassadorial posts and several unqualified people to key positions at the State Department.

The threat to personnel was multifold. It included, importantly, terrorism. The embassy in Beirut was twice car-bombed, with massive loss of life. Assassinations of American officials happened in other venues. The memorial plaque in the C Street Lobby of the Truman Building began to fill rapidly. There was also the onset of AIDS, the deadly and little-understood disease that threatened the “worldwide availability” of infected employees and thus the whole notion of foreign service.

It was a time when women were first cementing their gains in the workplace, fracturing the age-old paradigm wherein the uncompensated wife was rated on an annual basis alongside her Foreign Service husband. Now the woman was often the diplomat, or she had an independent profession. Dual careers and the challenges of raising children overseas were leading many families to simply refuse to move. Finally, the new Foreign Service Act of 1980 and the “up or out” system it created for senior officers was being implemented, to the benefit of diplomacy generally but also the consternation of many.

Seldom before was there a greater need for a professional magazine to offer guidance and an arena for robust debate of the issues confronting America’s diplomats.

AFSA wanted an active-duty-focused magazine guided by a peer-reviewing board made up of representatives of each of the foreign affairs agencies, as well as expert public members.

A Great Opportunity

The AFSA search committee had made it clear to me that they expected real improvement in the Journal. They wanted an active-duty-focused magazine guided by a peerreviewing board made up of representatives of each of the foreign affairs agencies, as well as expert public members. The FSJ Editorial Board drafted bylaws to codify these changes, putting in term limits to keep the membership fresh. An important innovation was to have a liaison officer; we put a member of the Governing Board on the Editorial Board so he or she could keep the big board informed as necessary.

I realized during the transition that the Journal had a great opportunity to become a true professional magazine for America’s diplomatic employees. That meant content that dealt with Foreign Service issues—including important articles on foreign relations, but written for a professional audience, as well as articles that addressed the unique aspects of overseas careers and lifestyles. I convinced the Governing Board to budget an assistant by promising an increase in ad revenues, and Frances G. Burwell, who held a master’s degree in international relations from Oxford, came on board to act as articles editor and chief salesperson. She made a critical difference in our editorial content and in our finances, more than paying her way in both contexts.

Fran and I reorganized the magazine with columns up front covering various beats important to diplomatic employees, followed by a series of Foreign Service-focused features. Finally, we preserved the remarkable overseas experiences that were the mainstay of the old FSJ by running a single such piece per issue at the back of the book, with a special layout and illustration.

Then we proceeded to secure a bunch of articles that cemented the new identity of the magazine. President Reagan had pulled out of the Law of the Sea Treaty that spring, and by coincidence a week earlier we had received a manuscript on the accord. We also obtained an article on the law governing outer space resources, which Reagan would soon threaten to militarize via his Star Wars missile defense program. In both cases, we were ahead of the curve.

No More Cover-ups

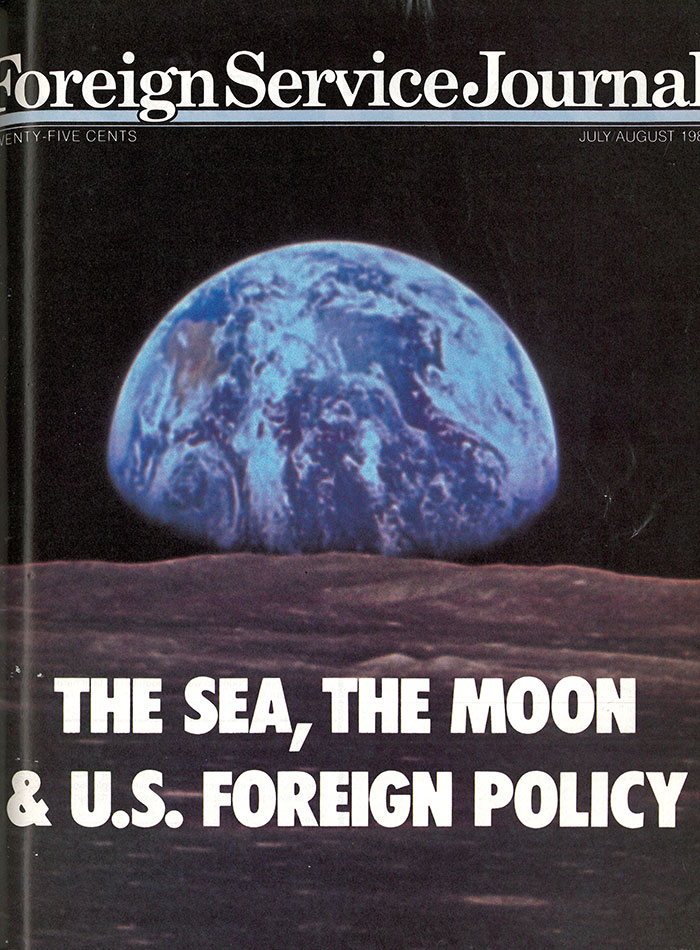

A “contraband” color photo of the Iraqi nuclear plant bombed by the Israeli Air Force earlier in the year was the cover of the September 1981 FSJ.

Until then, the Journal’s covers had been artwork by Foreign Service employees or their spouses. Sometimes these depicted overseas scenes, many of them charming and by a fine hand; but, even so, they were unrelated to the content of the magazine. And sometimes they were neither topical nor good art. Never was this disconnect clearer than in the April 1981 Journal.

Just weeks after the Iran hostages returned, my predecessor secured a coveted interview with Bruce Laingen, who had been the chargé d’affaires in Tehran, for the April issue. Laingen also gave the Journal a watercolor he had done while in captivity. It showed his view from the room where he had been held prisoner. He had smuggled it out of the country when the hostages were released by taping it to his thigh. Incredibly, this historically important and well-executed painting ran on an inside page in black and white, while the cover was taken up by a color folk art rendition of the Garden of Eden, with papier-mâché figurines of Adam and Eve showing prominent pubic hair.

We took a different approach. Beginning with the July/August 1981 edition and our sea and space articles, we sought covers that advertised the contents of the issue. For that issue, the Journal obtained from NASA one of the most famous photographs in history: the watery blue Earth rising above a barren moonscape taken by the Apollo 8 astronauts. Below that, in bold type, was the header: “The Sea, the Moon, and U.S. Foreign Policy” (see above). That cover announced via tone and content that the magazine was a professional policy magazine now.

The Journal then secured an interview with Sigvard Eklund, the little-known Swedish diplomat who had guided the International Atomic Energy Agency for 20 years. Just days later, the Israeli Air Force sent a bunch of bombers to take out Saddam Hussein’s nuclear power plant under construction at Tuwaitha. The Israelis feared it would be used to produce weapons-grade plutonium. The raid made a mockery of Eklund’s mission to promote nuclear power while ensuring that nations using reactors were not diverting materials to manufacturing atomic warheads in contravention of the Nonproliferation Treaty.

The Journal’s 4,000-word scoop—a taped interview with the reclusive agency head that included detailed discussions of the safeguards system meant to shield against proliferation—ran in the September 1981 issue. Through some creative sleuthing, we secured a contraband color picture of the Iraqi facility that had been snuck out of the country before the Israelis reduced the reactor to rubble. Once again, the Journal had a striking and important photo on the cover and an article that was both topical and of intense interest to foreign affairs professionals: the functioning of an international agency in the news with an ambitious and challenging diplomatic mandate.

These articles weren’t isolated points of light. That same September issue also contained an important essay on State’s diminishing role versus that of the National Security Council by former ambassador and Cabinet secretary Elliott Richardson, and an article on state-sponsored terrorism by none other than head Iran hostage, Ambassador Bruce Laingen.

We also printed covers by nationally known illustrators to feature our content, especially via humorous art. My favorite was a sketch by the New Yorker’s Henry Martin of a diplomat in tails meeting a penguin. The mirror twins were used to showcase an article on Antarctica in the February 1983 FSJ. For the September 1983 cover, the syndicated editorial cartoonist Henry Payne highlighted an article on ensuring ambassadorial quality by painting three identical pin-striped diplomats coming down an assembly line followed by an unnoticed Bozo the Clown. Former Ambassador James Spain joked on seeing that cover that he wasn’t sure the ratio shouldn’t be closer to 1:1.

“Ambassador Klunk” and Beyond

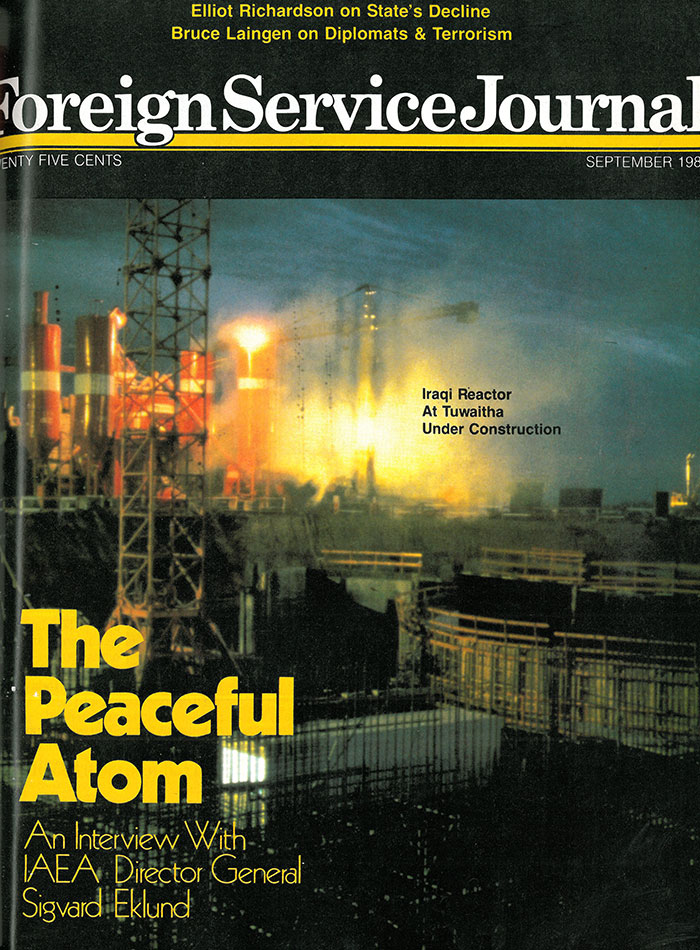

Amb. Malcolm Toon decried the “Mr. Klunks” among political appointee ambassadors in the April 1982 FSJ.

In the winter of 1982, I got a phone call from Malcolm Toon, a retired FSO who had been ambassador to the Soviet Union. With AFSA, he was concerned about the number and qualifications of political appointees named to ambassadorial posts. Fran and I interviewed him. Ambassador Toon referred to several appointees as “Mr. Klunks” and called out specific non-career ambassadors with further epithets, especially his successor in Moscow.

When the “Ambassador Klunk” article (April 1982 FSJ) hit the streets, it got huge play in the media. We submitted the story to the Society of National Association Publications’ annual contest with a ream of press clippings, and it received the gold award for outstanding article of the year at SNAP’s membership convention in June 1983.

A week later, the AFSA Governing Board was considering a Journal expense request. After it was approved, I showed board members the award plaque. The announcement prompted a hearty cheer from the room. Following the meeting, a State representative, who went on to have a distinguished career in the Middle East, pulled me aside and said that I should have announced the award first and only then asked the board to consider my expense request. In other words, I had committed a tactical blunder. So much for my thinking that acting honorably would have strategic value in future requests.

Our first years were a success editorially in repositioning the magazine. They were also the beginnings of real financial success, as we brought costs down sharply while dramatically increasing revenues from ad sales and a significantly larger membership attracted to the revamped magazine.

There was surprising resistance on occasion. One anecdote suffices to illustrate the point, but it was replicated in its illogic numerous times. In 1981 the association was spending $100,000 a year on manufacturing the Journal, a considerable sum. I secured a bid from Dartmouth Printing Company that would allow a savings of 30 percent. Then, however, our executive director complained to the Governing Board that we would now have to mail by first-class postage those dozen or so copies that needed to be sent out each month to new members who signed up after the labels were finalized. The current printer sent them out at the cheaper second-class rate. As I figured it, the amount at issue was about $10 per month. And for this, some were willing to forego an annual savings of $30,000. I prevailed in the end, but it was bothersome that it was even a contest.

Mind you, the Governing Board wasn’t necessarily picking on the magazine staff, as it ran the day-to-day operations of the entire association. For instance, the board placed a cap of $25 on individual expenses the director was empowered to approve. So when the toilet in the men’s room in the E Street offices clogged up, the director proceeded to seek bids from competent plumbers. But I could not wait till the next board meeting. I went next door to People’s Drugstore (now CVS) and bought a plunger for $4.95, came back, freed the toilet and was reimbursed out of petty cash. I had beaten the system.

That was the mundane, but there was also the exciting. One thing I enjoyed about running the Journal was the opportunity to meet and work with leading officials in government, including members of Congress of both parties and top people in the foreign affairs agencies. The highest official I met was Vice President George H.W. Bush, who had been invited to AFSA headquarters on short notice to address the Overseas Writers Club during a luncheon at the Foreign Service Club. The director was on leave, and I found myself named chargé. So I was the one who dealt with the Secret Service in planning the event. Now that more than three decades have passed, I can reveal that we agreed to secure the nuclear football in the vacant director’s office.

We sought covers that advertised the contents of the issue … and announced via tone and content that the magazine was a professional policy magazine now.

On the day of the event, after meeting the aide with the launch codes and locking her in the designated room, I was standing by the service door that opens onto 21st Street as journalists were coming through a metal detector in the E Street entrance. Suddenly the service door burst open and in walked the vice president. I was the first person he saw, and he strode right up to me, shook my hand and said how pleased he was to meet me. I was speechless. A few minutes later an officer of the writers group said some dignitary had failed to show, and so would I mind sitting next to Bush?

There was an empty seat behind the head table, and my new friend George the vice president was waving me over. The veep was being criticized at the time for not eating broccoli, so I had a chance for a scoop. Then the missing person suddenly showed up, and I was spared the opportunity.

Where We Stand

But for the most part, we concentrated on publishing the best content we could, and we were rewarded for doing so. Membership increased by 60 percent, advertising revenue more than doubled, and the press picked up our articles on an almost monthly basis.

It became routine for the national media to use our magazine to showcase issues of concern to the Foreign Service. When AFSA’s U.S. Information Agency contingent raised in our pages charges of political interference by agency management, it was network TV news. When a Journal poll conducted by Fran showed diplomats’ concern about terrorism, it was widely reported via broadcast and print outlets. An entire episode of William F. Buckley’s PBS series “Firing Line” was devoted to a column I wrote on professionalism in the ambassadorial corps and its discontents, “Galbraith & Guts” (April 1985 FSJ).

The Toon interview alone generated 200 clippings and several network TV reports, plus a star turn for the former ambassador on the “Today Show.” Our change in mission to be a higher-profile professional magazine was significant enough to be noted by the Federal Times, which said in a 1983 editorial that the Journal “frequently includes provocative, first-class essays—particularly since Stephen R. Dujack has been its editor.” Forgive me for tooting my own horn here, but we were clearly on the right track.

This state of editorial success and impact proceeded for six mostly happy years. The interval was not without untoward incident or other bumps in the road that brevity commands I omit, but the Journal continued its steady progress as a needed beacon during a critical period for diplomacy and for diplomats personally and professionally, and was duly recognized time and again.

During that period, the same faction had won the AFSA presidency and the key vice presidential posts on the Governing Board in each annual union election. I had served under a total of six presidents, but there was nonetheless constancy in board management.

Membership increased by 60 percent, advertising revenue more than doubled, and the press picked up our articles on an almost monthly basis.

Then, in the summer of 1987, I came face to face with one of the challenges implicit in AFSA’s unique structure as a combined trade union and professional association run by a board of individuals elected every year. A new and different bunch was voted in. Shortly after the transition, I had a conversation with the new president, Perry Shankle. He queried me about the Editorial Board. “Do we get to replace them?” he asked. I explained that members were elected for fixed terms. He instead forced the Editorial Board to accept him as the liaison officer.

Shankle began to dominate the Editorial Board, raising outrageous concerns and criticizing articles that it was clear he had not read. He also seemed immune to the fact that by putting himself on the Editorial Board, he became accountable as president to the membership for articles whose opinions he could otherwise wave off as the editors’ responsibility. A series of conflicts ultimately led to a joint meeting of the Governing Board and the Editorial Board on April 7, 1988, insisted upon by the president.

The majority of the Governing Board members disagreed with him. They liked the magazine. A lot. So the big board voted overwhelmingly to preserve the functioning of a professional magazine run by professional staff, knowledgeable journalists who would work with an expert Editorial Board to choose articles based on their merit and appeal to a diplomatic audience through peer review, not political considerations.

But the next day Shankle called me and asked for the end dates of the Editorial Board members’ terms. Seven years earlier we had put in our new term-limit provision, allowing for terms up to three years (although most members rotated overseas before completing their terms). By coincidence, several members’ terms would end in the coming months—five, in fact. He would get to name their replacements.

Exactly one week later I was named director of communications of the Worldwatch Institute. I have been an environmental editor ever since. My experience at the helm of the Journal gave me a wealth of knowledge of how the world works—and how association governance works—that has proven invaluable in my career since. I am grateful to AFSA for the opportunity and to the Foreign Service professionals for writing for us.

In my farewell column in the Journal, I praised the Foreign Service membership for its contributions to the cause of peace, development and human harmony—I could never make the sacrifices required of them, I acknowledged, and saluted their patriotism. And I saluted the Foreign Service for recognizing that a publication that promotes robust debate and reader service as “the magazine for professionals in foreign affairs” best aids the interests of America’s diplomats and the nation they represent.

A Massive Leak

At the height of the Cold War, a top official at State caused a leak of extremely sensitive material, classified above Top Secret. It was distributed far and wide—to nearly every country in the world. …How do I know? I was the agent of that massive leak.

Thus begins Stephen Dujack’s gripping account, in the June 29, 2016, edition of Politico, of an incident that occurred 30 years ago, during his tenure at the helm of the FSJ.

It had to do with the February 1987 Journal, which carried a “cover story” interview with Under Secretary of State for Management Ronald I. Spiers, the fourth-ranked officer in the department and former ambassador to Turkey.

In connection with the interview, Dujack visited Spiers’ office on the State Department’s seventh floor to take photos, then chose the best for the cover. Ten thousand copies of the FSJ were sent to AFSA members around the world, to offices in Foggy Bottom, to the diplomatic corps and the foreign affairs community in Washington, D.C., and to Capitol Hill.

When an aide to then-Senator Jesse Helms saw the Journal, he recognized a document partially visible on Spiers’ desk as a copy of the highly classified National Intelligence Daily and called the State Department’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security.

That’s when the real fun began—including a press frenzy that saw the story and millions of copies of the incriminating FSJ cover circulate around the country and the world.

The FSJ editor had committed no crime; he should not have been allowed in the room with the document unsecured. Though testing determined that no information could be gleaned from the photo, Mr. Spiers was reprimanded for the “infraction.”

—Susan B. Maitra