My Kingdom for a Door: When Multitasking Goes Awry

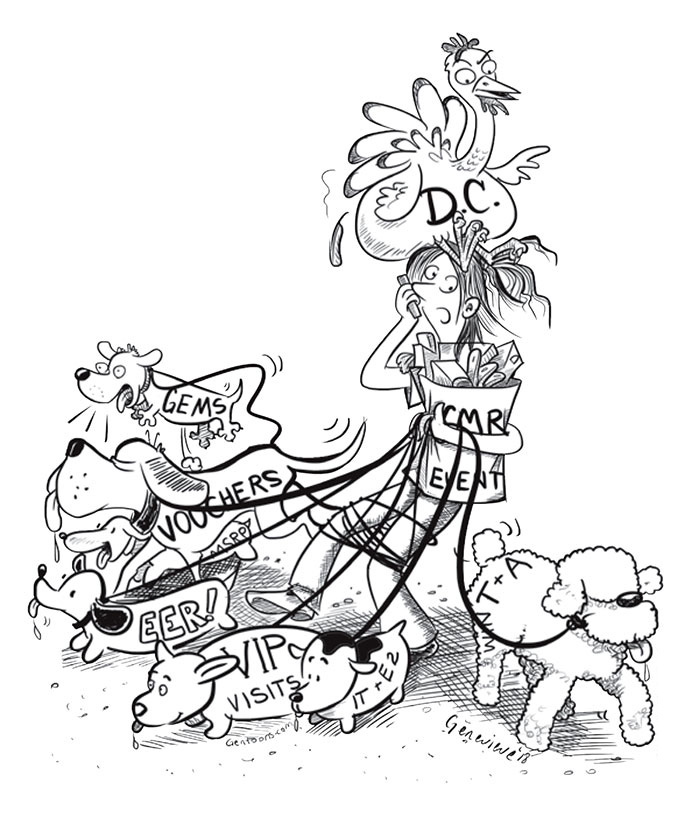

Office Management Specialists multitask perpetually, with masses of detail and constant interruption. A healthy dose of humor keeps inevitable mishaps and all the rest in perspective.

BY MARSHA PHILIPAK-CHAMBERS

Genevieve Shapiro

One morning early in my Foreign Service career, when the deputy chief of mission walked through the door, I greeted him with a heartfelt, “Good morning, sir! How was the reception last night?” He paused, briefcase in hand, before replying cheerfully: “Actually, when I arrived at Frank’s apartment, he met me at the door in his pajamas. It turns out the reception is next week.”

I stammered and stuttered, “Oh, my God, I’m so sorry! I have no idea how that happened, but I promise it will never happen again!” I was close to tears. “Oh, it’s OK,” he warmly reassured me. “Frank and his wife invited me in, and we had a nice cup of tea and a good talk at the kitchen table.”

I pictured a man in a bathrobe and a five o’clock shadow, his wife in curlers, and my stomach turned. But because, like nearly all my bosses, this DCM was kind, he saw, and helped me see, the humor in the mishap. Still, I remember feeling unsettled and nervous for weeks afterward, sure that I was bound to do something really stupid—like booking rival Russian mafiosi to arrive at the embassy at the same time. I envisioned them riding up in the elevator together, backed into opposite corners, guns drawn.

Fallibility plagues us all, of course. But for OMSes, who constantly multitask in microscopic detail, “oopses” are exponentially more likely. Add constant interruptions to the stew, and you have a recipe for disaster.

EERs? Eek!

Symptoms of multitask-itis include saying, “Bye! Love you!” to a boss just before hanging up the phone. A recent OMS poll happily indicates that I’m not the only one who occasionally mistakes the boss for the spouse or offspring when distracted. We love our bosses, don’t misunderstand, but not with quite that familiarity. Rather than being startled by it, the boss should simply return the sentiment with “I love you, too!” to avoid embarrassment. It’s the kind thing to do, and your OMS won’t remember it past the next phone call anyway.

One might assume that eventually one would get better at this, and one does to an extent—at least we learn when not to even try to get anything done, like during Employee Evaluation Report season.

Over the years I’ve developed a system for presenting ambassadors with the information they need to write an employee’s reviewing statement. I take great pride in anticipating my principals’ needs with neat little employee packets that are comprehensive and uniform. Preparing these materials makes me feel smart and efficient. I am a true Girl Friday, a right hand, a veritable genius.

Unfortunately, while I’m putting the packets together, I’m also fielding scores of emails and phone calls with requests like, “Can you push my statement forward?” “I’m good with it; can you just paste it in?” or “The panel wants me to insert a comma after ‘approachable’—can you do it?”

And while I’m feverishly, frustratingly, working in the GEMS system to comply, I’m also talking to people who come to my desk, putting appointments on the ambassador’s calendar, answering non-EER-related phone calls, running to the outer door to fetch something from someone—and hopping up every time I hear cries of “Marsha!” from the ambassador’s office because her screen is frozen, or GEMS won’t load.

Inevitably, at some point the ambassador summons me again and, with a puzzled look on her face, asks why James’s rating statement is in Chris’s EER. It takes a moment for me to recall that because the DCM OMS was busy making the DCM’s employee statement fit in its box, I had jumped in to help keep things moving by pasting Chris’ and James’ new, abbreviated versions into the appropriate boxes (which, by the way, I am convinced shrink with use). God only knows what interruptions occurred while I was doing so, but they ended up swapped. Too frazzled to feel shame, I simply say with a heavy sigh, “It was a test to see if you were paying attention, and you passed.”

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve truly been blessed with bosses who have a sense of humor.

“Bad for My Organism”

Your OMS corps isn’t inept. We are just acutely doorless, exposed to constant interruptions. There are days when we want to shout, “Go away! I have to get this done!”—but, of course, we do not. We love our colleagues and I’m pretty sure they love us, though I sometimes feel it’s rather in the way a village loves its idiot.

As an ambassador’s executive assistant, my job is to put her day together before she arrives and stay until she leaves, which is often late due to receptions or dinners in town. While that makes for long days, it also gives me time to catch up on tasks that require sustained focus—pretty much anything that requires reading or writing.

Even when an officer or section’s schedule is relatively light, office management specialists still have to anticipate and prepare for what is coming up. And we can’t do that if tasks are “sitting on our heads,” as one of my Botswanan colleagues used to say. No, attempting to operate that way would be “bad for my organism,” as a Ukrainian friend once put it.

I learned a long time ago that it’s good for my organism to come in very early. When I arrive in the morning, the guards are just lining up for their morning brief. Upon entering the building, I greet the Marine at Post One and struggle to open the 12,000-pound door without dislocating a shoulder. The aroma of bacon greets me, and I am compelled in my sleep-walking state into the cafeteria. The helpful staff understand that I cannot yet form a sentence other than “Good morning,” so they know just to hand my well-done bacon to me. As my brain starts to wake up, I slide my briefcase and bacon down to the cashier, order lunch and pay (because I know how hard it will be later to make it back to the cafeteria).

Once upstairs, I put my cell phone in the box and try to open another six-ton door without dislocating a shoulder or, more critically, dropping my bacon. After entering the code—the right one, mind you, from the innumerable combinations and codes we OMSes have swimming about in our heads—I make my way down the hallway to the door of the front office, where I must come to a complete halt. I set down the briefcase and the bacon and reach inside the briefcase for my reading glasses so I can see the microscopic lines of the spin dial. (Muscle memory is useless here. If I leave my glasses at home, it begins a sequence of events so ugly that I’d be better off turning around and going back to bed.)

After at least two tries on the spin dial, I open the door and launch myself inside to quickly silence the beeping of the alarm by putting in yet another code. The reading glasses are still on—there’s no time to take them off and put them back on before I have to see the alarm panel—so attempting to move quickly is “bad for my organism.” Because anything further than two feet from my face is a visual mystery, I invariably clip my leg on the edge of the DCM OMS’ desk and yelp, which assists with the waking-up process.

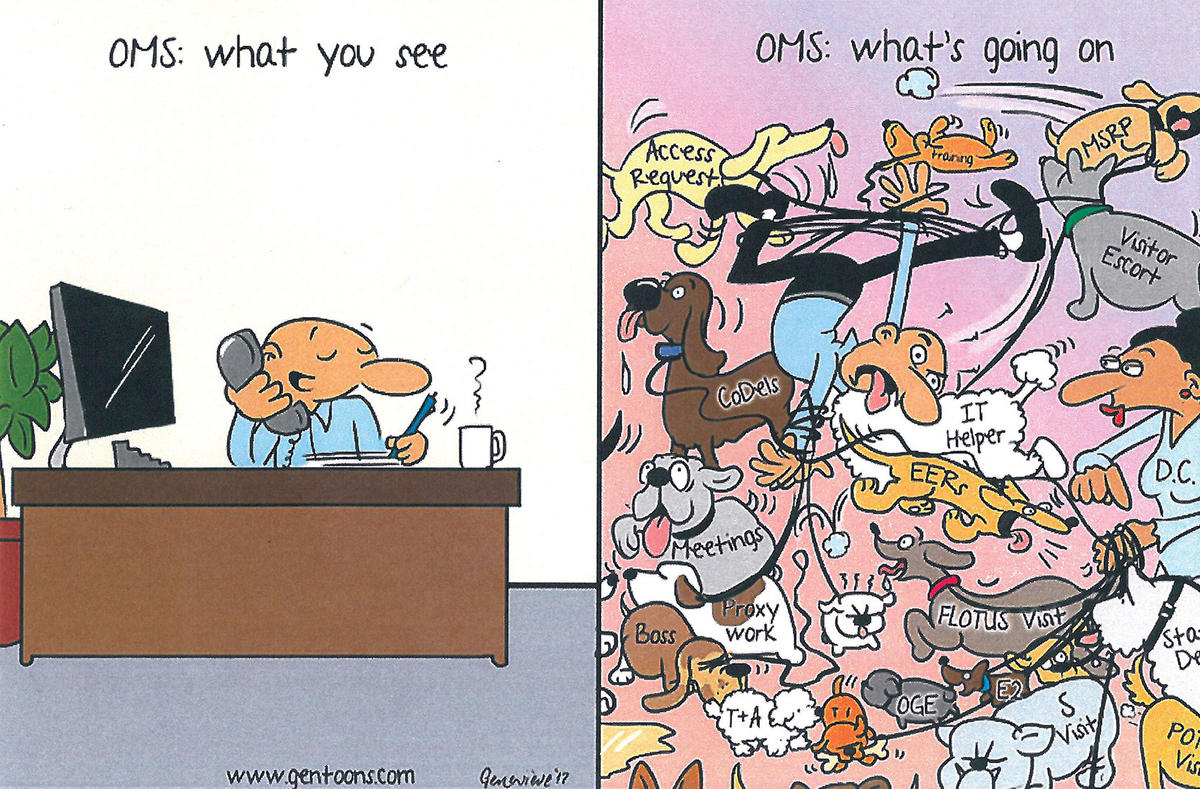

Genevieve Shapiro

OMS Heaven

I then go back out the door, fetch briefcase and bacon, and move to my desk where I set everything down, including myself, and breathe for a minute. I have approximately one hour to prepare for the onslaught of the day. Because, like me, the computer is multitasking while trying to wake up, I throw my card into the reader while I make my tea. This gives the device time to yawn, stretch and do a bit of yoga. If Washington has pushed out a patch or upgraded something or other, then I must patiently wait until 8:30 when an Information Resources Management colleague can cajole or threaten my computer into behaving.

On days when the system likes me, and the tea and bacon are working their magic, I’m prepared to greet the ambassador with the full spectrum of my vast knowledge. By the time she arrives, I have ironed out every detail of her day, prepared myself to answer any question she might have, printed the calendar far into the future for the country team, or whatever meeting happens to be that morning, and have compiled a list of decisions I need her to make.

I am most pleased with myself, basking in the glow of my efficiency—until I review the printed, far-into-the-future calendar and see that I have put an event on the right day but the wrong month. At times like this, I dream of a career selling vegetables on the square of some small Midwestern town.

At some posts, like my previous one, Kyiv, OMSes dream of a place where the day actually ends. But here in Bridgetown the day not only ends, but it does so early, leaving just the ambassador, DCM and a smattering of section or agency heads. For those of us with no door but a huge “to do” list, the resulting drop in the volume of phone calls, emails and visitors is heaven. We can complete entire thoughts and tasks—efficiently making travel arrangements, writing evaluations for subordinates, creating better knowledge management organizational systems and answering any emails that require more than a sentence.

Staying after hours is not overtime abuse, but time away from our personal lives that OMSes willingly sacrifice because we have integrity and take our work seriously—particularly if there is a project looming that requires several hours of concentration. Like most department personnel, we will do whatever it takes to get the job done—and can only see it through when we’re not multitasking.

“Where Is Oleg Taking Me?”

Office management specialists aren’t the only employees to suffer from multitask-itis. During a crisis, multitasking can get completely out of control, the inbox fraught with peril. On one occasion, while serving at a post in crisis where we got hundreds of emails in a non-stop, 24-hour work day, I received a five-word email from my ambassador: “Where is Oleg taking me?” Copied to all staff at post, as well as to the task force and Eastern European desk back in Washington, it was an urgent, if somewhat broad, cry for help.

Confident that Oleg, his driver, was not kidnapping the ambassador, I called the political officer who was already at the location to find out what the ambassador might be referring to. The political officer confirmed that the meeting location had changed on short notice, and pointed out that he had emailed me with that information. Sure enough, amidst the drop-ins, the phone calls and the blizzard of emails with subject lines that shed little to no light on their content, I had not picked out that particular one; but the ambassador, frantically reading emails in the car, of course had.

Assuming that the ambassador had not leaned forward from the back seat to inform Oleg of this new destination because he was dealing with his own multitasking frenzy, I dealt with the situation quickly with a few phone calls and then sat back and tried to breathe.

Having seen the “Where is Oleg taking me?” email (who didn’t?) and heard my end of the corrective phone calls, the DCM, also a member of the multitask-itis sufferers support group, sauntered out of his office with a wry smile on his face. “So … what’s the deal, Marsha?” he asked, leaning casually on his OMS’ counter. “Where is Oleg taking him?” His jovial sarcasm served as a flotation device for a drowning woman, especially since I received emails for the rest of the day from concerned people in Washington asking who Oleg was, where he was taking the ambassador, and what it all meant. I suppose they thought it was some kind of code, like “The eagle has landed.”

Late that evening, when it was quieter and I could focus, I made a list of “rules of engagement” for passing critical or urgent emails to the front office: updated subject lines that specified the action, using caps to signify action, and for whom, etc. But forever after, “Where is Oleg taking me?” was synonymous with too many emails and too much multitasking in our crisis-ridden front office.

Multitasking on the Homefront

OMSes are so conditioned to interruptions and task-jumping that fractured thinking doesn’t end at the office door. When doing my Saturday chores at home, I’ll start to do something upstairs, get halfway up and realize I forgot to bring a needed item with me. Then, when back downstairs to get it, I’ll see something else that needs doing—and immediately forget what I came downstairs for in the first place. Rinse and repeat.

We even do it in our sleep. I’ve awakened so many times in the middle of the night, suddenly recalling a detail I missed or something I need to do, that I keep a pad and pen on my nightstand. At least in Barbados, I’m finally getting good REM sleep. In crisis posts, or those that are simply very busy, REM sleep is a distant dream, so to speak.

Fractured thoughts from too much multitasking cause good OMSes to do things like email the entire embassy to hold the mayo on their lunch order, call the ambassador “hon,” forget the name of one or more of their children, or forget which country they’re currently serving in or what year it is.

The moral of these tales is this: Please employ patience and humor when your OMS makes a mistake. After all, even computers lock up when they’re trying to process too many details at once.

At least your OMS will occasionally tell you she loves you. When was the last time you heard that from your computer?