Now It Can Be Told

Steering a dynamic and adventurous professional magazine involves challenges as well as accomplishments.

BY STEVEN ALAN HONLEY

December 2001 cover.

When the Journal editor invited me to reflect on my tenure (2001- 2014) as editor-in-chief of The Foreign Service Journal for this issue, I was delighted to accept. After all, who doesn’t enjoy rehashing past triumphs?

With the help of a true dream team—Shawn Dorman, Susan Maitra and Ed Miltenberger, all of whom are still on the job, I hasten to note—along with dedicated Editorial Board volunteers and other AFSA staff, the magazine became an adventurous, thoroughly professional publication by time I stepped down.

When I took over, we were proofreading, marking up and couriering actual blueline pages to our printer, then located in New Hampshire, each month. (And yes, that process was every bit as tedious and inefficient as it sounds.) Now production is done online, with a printer in Richmond, Virginia. As a result, even though the typical issue of the FSJ is at least a third longer than it was back in 2001, it is far less cumbersome to publish it.

Early in my tenure, I expanded the practice of penning Letters from the Editor, and introduced or revamped several departments and features that are still around: Talking Points (originally Clippings, then Cybernotes), FS Know-How (initially known as FS Finances), FS Heritage and In Their Own Write.

I also pioneered the use of the AFSAnet listserv to invite Foreign Service members to share their experiences with various policies and career challenges, as well as responses to wars, terrorist attacks, natural disasters and other international events. Compilations of those contributions quickly became, and remain, a cornerstone of FSJ coverage.

In all our coverage of the so-called “War on Terror,” we strove to strike an appropriate balance between being supportive and skeptical.

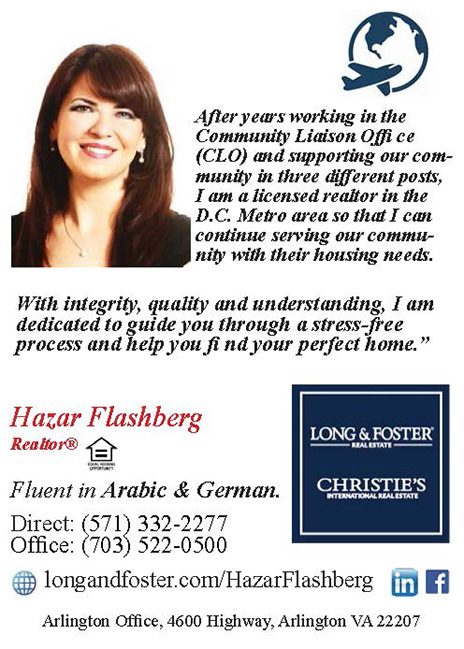

And, during my tenure we gave the Journal an entirely new and updated look, undertaking a wholesale redesign of the magazine in 2011 after nearly two decades.

While I could go on (and on…) about those accomplishments, I thought it would be more useful to describe some of the challenges, both internal and external, I faced as editor, and how I met them. However, because the statute of limitations is not quite up yet, where necessary I will withhold names to protect the guilty—and myself. First, allow me to set the stage briefly.

In the Beginning

Transformational Diplomacy” was the focus of the July-August 2006 FSJ.

I’ve been a dues-paying AFSA member for nearly a third of a century now, ever since joining the State Department in January 1985 with the 25th A-100 class. Part of a massive hiring surge, my class of 52 Foreign Service officers was one of the largest since the Vietnam War era.

Beyond dutifully voting in Governing Board elections, I must confess that I wasn’t an active AFSA member during my 12-year career. I read the Journal, of course (though I tended to save up issues for vacations), but I never submitted anything for publication, not even a letter.

Shortly after I was tenured in 1989, the Berlin Wall came down and the Cold War entered its final phase. But the much-vaunted “peace dividend” did not accrue to the foreign affairs agencies. Instead, by the end of the 1990s congressional critics like Senator Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) had succeeded in disbanding the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and the U.S. Information Agency, and folding their functions into the State Department. Adding insult to the injury of a mounting workload, State, along with the U.S. Agency for International Development, Foreign Commercial Service, Foreign Agricultural Service and International Broadcasting Bureau, faced severe budget cutbacks and unrelenting pressure to “do more with less.”

That adverse climate was not the primary impetus for my own decision to leave the Service to pursue a career in music and writing, but it certainly made the decision easier.

Soon after I left State in August 1997, a dear friend and A-100 colleague who was on the FSJ Editorial Board at the time, Mitchell Cohn, approached me to write a short-fuse article on consular fraud when the original author was unable to fulfill the contract. That came out well enough that Bob Guldin, my predecessor as editor-in-chief, commissioned me to write several more articles on various subjects, and then hired me as associate editor in April 1999.

Though only a half-time position, the job nonetheless gave me a taste for greater responsibilities, such as putting together several focus sections; interviewing each year’s winner of AFSA’s recently instituted Award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy for a lengthy profile; and lining up and writing book reviews, one of the most enjoyable perks of my time at the magazine.

When I succeeded Bob as editor-in-chief on July 1, 2001, my appointment was on an interim basis. But on Nov. 1 of that year, I took over officially and occupied the position for more than 12 years—a span second only to that of the legendary Shirley Newhall, FSJ editor from 1968 to 1981.

War Reporting and Expeditionary Diplomacy

FSJ Editors Shawn Dorman, Steve Honley and Susan Maitra with FSJ Editorial Board Chair James Seevers at the redesign launch in October 2012.

The 9/11 attacks occurred barely two months into my editorship. Despite our lead time as a monthly magazine, and the massive uncertainty we were all facing in the aftermath of the attacks, the November 2001 issue featured a compilation of AFSA members’ reactions and policy recommendations. The December 2001 FSJ offered a second installment, along with a meaty focus section devoted to “Shedding Light on Sept. 11.” Apart from the regrettable caricature of a glowering terrorist on the cover, I believe we did exactly that.

To cite just one example: “The Taliban-Bin Laden-ISI Connection” by retired FSO Arnie Schifferdecker (December 2001) set the stage for our ongoing coverage of the Afghanistan War by explaining authoritatively how al-Qaida was able to use that country so effectively as a base of operations. In the process, it also showcased the expertise and perspective that have always been among the Foreign Service’s fortes.

In all our coverage of the so-called “War on Terror,” we strove to strike an appropriate balance between being supportive and skeptical. There was no template to follow, of course, and I’m sure we ran some articles, letters and Speaking Out columns that were either too gung-ho about, or too harshly critical of, the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy. But I remain proud of our overall record.

Soon after the Bush administration launched the invasion of Iraq in March 2003, we gave three FSOs who resigned in protest—John Brown, John Brady Kiesling and Ann Wright—space to explain their reasoning. That energized debate in our letters section about professional responsibility in the face of directives with which one fundamentally disagrees: Is it more principled to stay on the job and try to steer policy in the right direction, or resign from the Foreign Service so you can speak out publicly?

Iraq was far from the first controversy to stir such arguments, of course. Nor, as we are seeing today, was it the last. But wherever you come down on any of those particular challenges, I trust we can all agree that it is vital for the Journal to be a forum for discussing them without fear or favor.

Wherever you come down on any of the particular challenges the Foreign Service faces, I trust we can all agree that it is vital for the Journal to be a forum for discussing them without fear or favor.

The Foreign Service community was hopeful that Secretary of State Colin Powell’s Diplomatic Readiness Initiative would revitalize the Foreign Service after a decade of neglect, and worse. With the end of the Cold War, legislators had come to believe that wholesale cutbacks in the international relations budget were appropriate. DRI did indeed repair a lot of that institutional damage, as did Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton’s Diplomacy 3.0 program later, and our coverage highlighted those encouraging developments in the midst of so much angst about the future.

Unfortunately, the “Iraq tax”—the evocative shorthand for Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s policy of pulling resources from overseas posts and Washington bureaus to support the growing U.S. presence in the Middle East—and her championing of “transformational diplomacy” undid much of that progress. Nor did it help that resentment within the Foreign Service of such ill-conceived policies, which the FSJ faithfully reported, fueled perceptions of disloyalty—which we also covered. But short of turning into a cheerleader for the administration, I don’t see any other way we could have handled such fraught issues.

Getting It from Both Sides

The October 2012 FSJ, the first issue following the redesign.

In 2000 the AFSA Governing Board updated the FSJ Editorial Board’s bylaws (now called “guidelines”) to specify that the magazine’s primary mission was to publicize and promote the American Foreign Service Association’s many activities on behalf of its members and to bring them “news you can use.” The Journal was also tasked with continuing to publish reporting, analysis and commentary about the Foreign Service and foreign affairs, with a goal of maintaining a roughly 50/50 ratio between those two broad purposes.

There was little doubt that the former goal outweighed the latter as far as AFSA management was concerned. But it was not at all clear, at least to me, just how much leeway AFSA members had to use the FSJ to criticize Governing Board decisions—until a test case presented itself.

Back in the spring of 2001, while I was still associate editor, an FSO submitted a Speaking Out column that denounced AFSA for working with Gays and Lesbians in Foreign Affairs Agencies to overturn discriminatory practices at the State Department and other foreign affairs agencies. The FSJ Editorial Board reluctantly approved the column for publication, with the proviso that a response from GLIFAA run alongside it.

I suspect GLIFAA would have jumped at the chance to weigh in anyway, but the fact that I was a founding member, and had served as its president from 1996 to 1997, clinched the deal. The resulting point-counterpoint in the September 2001 issue, my first as interim editor, inspired a series of letters from readers over the next several months.

Most of the writers praised AFSA for standing by GLIFAA, but several sided with the complainant and took us to task for commissioning a companion piece, rather than leaving it up to someone to respond in a later issue. (Looking back, I have to agree that the optics of doing it the way we did were not great, but I don’t see anything unethical about it.) Still others lambasted us for publishing the original Speaking Out column criticizing AFSA in the first place.

That pattern would repeat itself over the next dozen years of my editorship just about every time we ran any submission on a hot-button issue. But it was well worth it to uphold the Journal’s proud tradition of letting members have their say, no matter how many people disagree viscerally with the viewpoint expressed.

The Bird Imbroglio

The Journal’s December 2011 focus on the Foreign Service in the USSR was groundbreaking; its December 2016 focus 25 years later on “The New Russia” won a silver medal in the June 2017 Association Media & Publishing EXCEL Awards Competition.

That principle received perhaps its most severe test (during my tenure, at least) in June 2002, when we published a feature titled “Arab-Americans in Israel: What ‘Special Relationship’?” Its author was Jerri Bird, president and founder of Partners for Peace, a nongovernmental organization formed to educate the American public about key issues in the effort to secure peace and justice between Palestinians and Israelis. She was also the wife of FSO Eugene Bird, who, like his wife, was a Middle East specialist.

Although Editorial Board members agreed the manuscript needed careful editing to remove the most incendiary language, they voted overwhelmingly to publish it. Ironically, Jerri Bird fought me every step of the way on the edits, and threatened more than once to pull the piece—a bluff I happily called, since I could foresee the firestorm the article would generate. But she eventually admitted that the piece really was more effective in its slightly toned-down form.

I don’t know how State found out her article was in our pipeline, but that spring the Bureau for Near Eastern Affairs formally requested that AFSA drop it. When that didn’t work, the NEA front office summoned me to a meeting to “discuss” the matter further. I no longer remember the deputy assistant secretary’s name, but he solemnly warned AFSA Executive Director Susan Reardon and yours truly that the situation in the region was so volatile that any criticism of Israel could have grave consequences—up to and including war. (Yes, he really said that.)

We agreed that such an outcome would indeed be unfortunate, but pointed out that, though critical of Israel, our interlocutor had not stated anything in the article that was untrue. We therefore published it in June 2002 as planned.

That was a proud moment. But in the immortal words of Clare Boothe Luce that I love to quote: “No good deed goes unpunished.” Over the summer, the pro-Israel organization HonestReporting organized a massive campaign that sent hundreds of vituperative letters, emails, faxes and phone calls my way. (I shudder to imagine the volume of the protest had social media existed back then.)

To top it off, I got a death threat on my answering machine from someone calling himself a “defender of Israel,” which we immediately passed on to the Bureau of Diplomatic Security. There was nothing DS could do, of course, but I still felt better that they knew about it.

Though I did not disclose that threat to our readers, I did publish HonestReporting’s form letter critique (unfair as it was) in September 2002, along with reactions to the article from Foreign Service folks. Most of the people who wrote us over the next several months were broadly supportive of our decision to publish Bird’s article, but several AFSA members excoriated us for it. Others attacked us for acknowledging the very existence of opposition to her perspective.

Awards and Demerits

This mock FSJ cover was presented to Steve Honley on his departure.

Appropriately, the focus of the June 2002 issue that included Bird’s article was a topic near and dear to my heart: celebrating dissent in the Foreign Service. Each year during my tenure, we devoted more pages to promoting AFSA’s dissent awards program (which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year) and gave the nomination process more prominent coverage, both in AFSA News and in the “white pages.” (The performance awards tend to draw plenty of nominations on their own.)

Unfortunately, such efforts were not enough to overcome what I saw as a seismic shift within the Foreign Service culture away from dissent that began about that time. I’ll spare you my theories about why that happened (you’re welcome!), but the general trend line is undeniable: Fewer and fewer FS members have been nominating colleagues in each of the four dissent award categories. As a result, in some years only one or two people have received dissent awards at the annual ceremony. I can’t say whether that situation has improved since I stepped down, but I would be pleasantly surprised if it has. [Editor’s note: In 2014 and 2015, all four dissent awards were given; in 2016, only one; and in 2017, three.]

Lamentably, AFSA’s Awards and Plaques Committee refused even to consider the possibility that it needed to change its approach to promoting the program. Instead, its leadership mounted increasingly personal attacks on me and my FSJ colleagues, alleging that “the Journal” was deliberately sabotaging the dissent awards for some unknown reason I still cannot imagine.

When I got wind that the chair of that committee was lobbying the Governing Board to fire me, I asked to see the AFSA president to defend our record. I documented the fact that we were already doing nearly everything our critics demanded to promote the dissent awards and encourage AFSA members to nominate colleagues or themselves. (I did balk at putting the dissent winners’ photos on the cover, since I didn’t think our members wanted their professional magazine to resemble a high school yearbook.) I had even calculated how many pages of each issue we had devoted to coverage of the awards program for the past five years (quite a few), and presented those figures.

None of that mattered. The AFSA president simply told me that I needed to do whatever it took to address the Awards and Plaques Committee’s concerns. That moment was the first time in nearly a decade that I thought seriously about resigning, but my native stubbornness kicked in, and I decided to stay the course. As a last resort, I drew on the negotiating skills I had supposedly acquired during my Foreign Service days to arrange a summit between the Editorial Board chair and the Awards and Plaques Committee. That meeting didn’t really resolve anything, but the campaign to oust me lost steam afterward.

Not too long after I left the editorship on my own terms in 2014, the Governing Board finally did something many of us had been urging for years, which was to enforce term limits on AFSA committees (a practice the FSJ Editorial Board had instituted way back in the 1980s). As a result, the entrenched critics on the Awards and Plaques Committee finally lost their stranglehold on that fiefdom.

And yes, just in case you’re wondering, that news brought me considerable satisfaction.

Thanks for the Memories

Speaking of satisfaction: Now that I’ve dished enough dirt in this article to fill several buckets, I want to end by underscoring just how grateful I am to AFSA for trusting me to shape and steer The Foreign Service Journal for more than a decade.

As with any job, some days (and months and years) were better than others. And, particularly toward the end of my tenure, I frequently had to remind myself that what I was doing really was worth the angst and long hours.

As I put it in my valedictory Letter from the Editor in the January-February 2014 FSJ: “I have relished the opportunity this job has afforded me to promote discussion and debate of issues related to foreign affairs and the Foreign Service, an institution I’ve been privileged to be associated with in various capacities for nearly 30 years.”

Here’s to the Journal’s next century!