A Century of Journals

The Foreign Service Journal’s first hundred years is a lively story of the development of an engaging and authoritative professional magazine, by and for the practitioners of American diplomacy.

BY HARRY KOPP

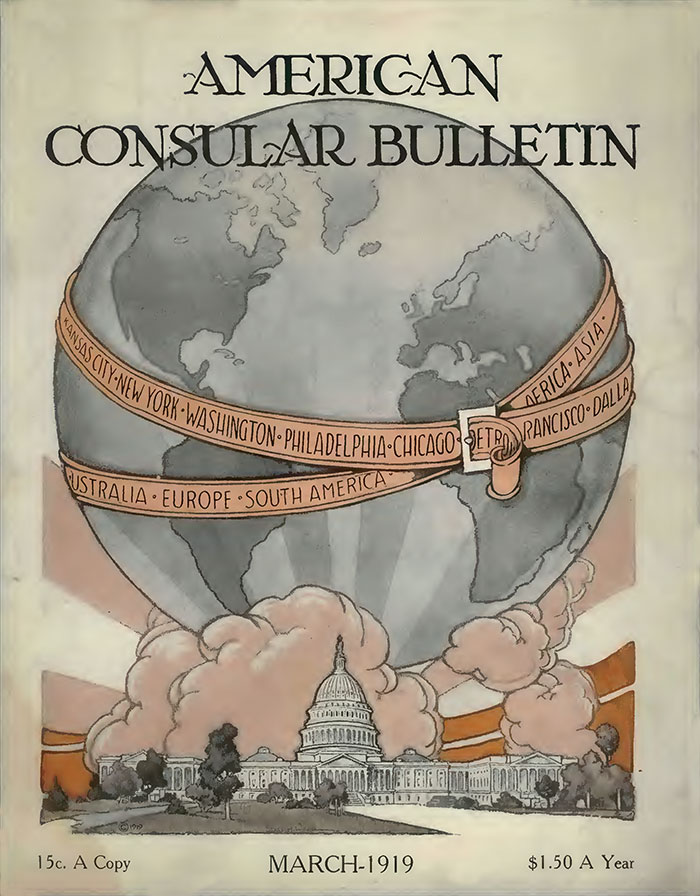

The first print edition, March 1919.

“When a diplomat wants to talk,” wrote novelist John Le Carré, “the first thing he thinks of is food.” No wonder then that The Foreign Service Journal got its start in a restaurant, the long-gone Cushman’s at 14th and F Streets Northwest, where the American Consular Association held its monthly meetings. The association, established in 1918 for social and professional purposes, had struggled to put out an occasional newsletter, of which no copies survive. A happy stroke of nepotism, however, led in March 1919 to the first printed American Consular Bulletin, edited and published in New York “with the cooperation of the American Consular Association” by the brother of an active-duty consul and association member.

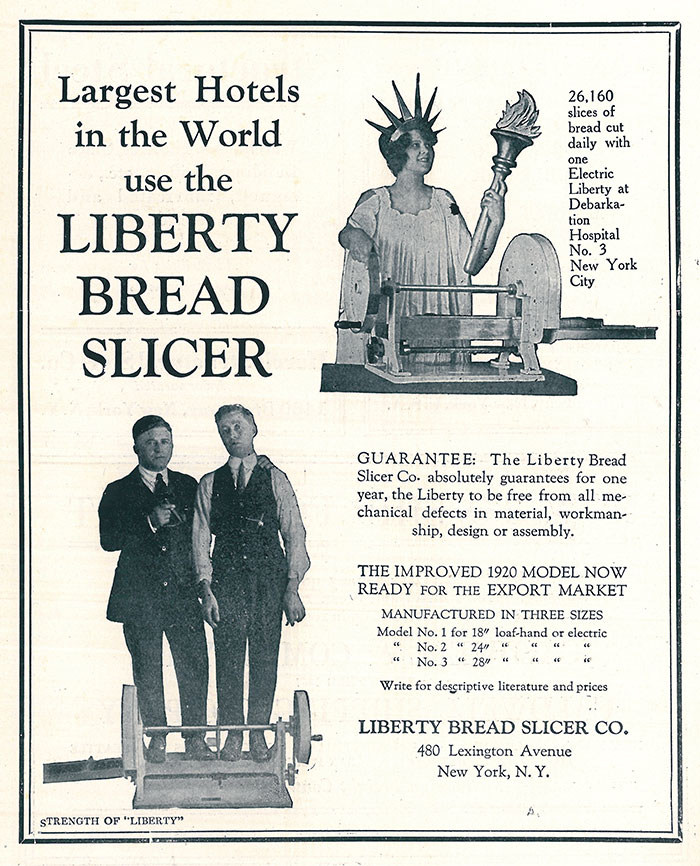

The ACA and its publication were intended to foster esprit de corps and seriousness of purpose in a Service that was rapidly becoming professional. In 32 pages a month, the Bulletin published important texts (e.g., the economic clauses of the Treaty of Versailles), opinion pieces (“Why We Must Reform Our Diplomatic Service”), commercial information (foreign markets for American-made candy), technical advice on consular matters (how to handle advance payment of wages to seamen) and information on pending legislation, congressional debates and personnel actions. Revenue came from subscriptions at $1.50 per year, with additional income from advertising—the Liberty Bread Slicer, which could cut 26,100 slices in a day, often bought a page.

The State Department found the idea of an independent publication deeply unsettling and insisted on prepublication review of every issue.

With his signature on the Foreign Service Act (also known as the Rogers Act) on May 24, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge merged the consular and diplomatic services into a new Foreign Service of the United States. The American Consular Association and its Bulletin promptly adapted, becoming the American Foreign Service Association and the American Foreign Service Journal, first published under that title in October 1924. The transition was seamless, although monthly meetings moved from Cushman’s to a larger room at Rauscher’s on Connecticut Avenue.

The State Department found the idea of an independent publication deeply unsettling and insisted on prepublication review of every issue.

The transformation brought immediate changes. Perhaps because the diplomatic service was smaller (128 diplomatic officers to 518 consular officers) and more deeply rooted in patronage, the new Journal, now edited and published in Washington, was less earnest and more chatty than the Bulletin. The change was clear from the statement of purpose that appeared below the masthead in the first issue: The main purpose of the Journal will be inspirational and not educational.… Photographs, the light touch in the narration of experience, and personal items will be constantly desired. Propaganda and articles of a tendentious nature, especially such as might be aimed to influence legislative, executive or administrative action with respect to the Foreign Service or the Department of State, are rigidly excluded from its columns.

“Greater Frankness”

Full-page ad in the May 1919 Journal.

The early Journal was a cross between National Geographic and today’s State Magazine. It carried travelogues, photographs of exotic places and people, sketches of life in the field, odd bits of history and lists of personnel appointments, transfers, promotions, retirements, weddings, births and deaths. So anodyne was it that the department gave up its demand for prior review.

Readers seem to have found the Journal boring. In October 1929, five years into its run, the Journal noted a decision by AFSA’s Executive Committee (the predecessor of today’s Governing Board) to take the publication in a different direction, toward “greater frankness” in discussing “problems and difficulties that may confront the Service.” For the first time, the Journal hired a full-time editor, a retired consular officer. The statement of purpose disappeared.

An opinion piece, published in December 1929 and signed by the chairman of the association’s executive committee, confirmed the change. After several years of budget cuts, Dana Munro wrote, many Service members “are profoundly discouraged … about the future of the Service,” as shown by “the appalling number of recent resignations.” Munro, who considered the despairing mood seriously overblown, urged Service members to contribute to a “frank and full discussion” of the problems of the Service “in the privacy of the Journal’s columns.”

Despite Munro’s appeal, echoed occasionally in plaintive letters to the editor, the next few years saw little in the way of debate about active issues confronting the Service. According to Smith Simpson’s account of the Journal’s first 60 years (November 1984 FSJ), signed articles in the early years came almost exclusively from members of the old consular service. “Diplomats virtually boycott the Journal,” he wrote, blaming their attitude on “their dislike of the Rogers Act [the Foreign Service Act of 1924] and anything associated with it.” Nevertheless, the historian Hugh de Santis, in a book excerpt published in the Journal in 1979, said the Journal, despite its “breezy, gossip-style format … reinforced organizational cohesion” and helped “to cement the diplomat’s professional identity.”

Henry Stimson, who took office as President Herbert Hoover’s Secretary of State in March 1929, was more intense and demanding than his predecessor, and the Journal’s tone took on some of Stimson’s seriousness. The number of articles on the work of the department and its diplomats increased, and coverage of social trivia diminished. Stimson persuaded the president and Congress to raise salaries and allowances for the Service and authorized an increase in hiring.

Depression and War

But the respite was short-lived. As the Great Depression deepened, President Herbert Hoover and Congress put together an austerity budget in 1932 that imposed deep cuts across the government, including in the department and the Service. The Journal accepted austerity as inevitable, as politically it no doubt was; but bitterness was evident in a sarcastic item hidden like a want-ad in the September 1932 Journal: “WANTED: A nice poorhouse, with all modern conveniences, where a Foreign Service officer can spend his 30-day furlough without pay.”

The Service, by and large, had little sympathy with the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration that took office in March 1933. The Service at the time was, indeed, as it was later called, pale, male and Yale. Photographs of all 683 Foreign Service officers published in the Journal in November 1936 showed 681 white men and two white women. A table published in June 1940, when there were 850 FSOs, identified 211 (25 percent) as graduates of Harvard, Yale or Princeton. An FSO, writing to the Journal in 1954, commented: “Anyone who knows the Service also knows that in the main it is composed of very conservative and cautious men and that during the 20 years of the Democratic administration it never contained more than a handful who were personally in sympathy with the social objectives and attitudes of the New Deal and the Fair Deal.”

In 1937 Selden Chapin, who would later design much of the structure of the Foreign Service Act of 1946, contributed a two-part article proposing major changes in the operation and administration of the Foreign Service and its personnel, with the goal of promoting greater training and specialization among officers. Chapin’s articles in the November and December issues received the Journal’s support in an “Editors’ Column” (which in mid-1937 became a regular Journal feature), but neither Secretary of State Cordell Hull nor the White House showed interest in the topic. The White House found it easier to ignore the Service than to take on the task of reforming it.

Throughout the 1930s, neither AFSA nor the Journal would have described itself as the voice of the Foreign Service.

Discussions of Foreign Service reform faded from the Journal’s pages. In 1939, the closure of the separate foreign agricultural and commercial services led to the transfer of more than a hundred outsiders into the Foreign Service at the Department of State. The Journal published the names of the newly commissioned officers, but otherwise said not a word.

Throughout the 1930s, neither AFSA nor the Journal would have described itself as the voice of the Foreign Service. That role belonged, without question, to the Department of State. The Journal published, almost always without comment, full texts or summaries of statements by department officials on matters affecting the Service, particularly legislation, appropriations and allowances. The Journal also reprinted a good deal of third-party content—editorials and articles from various U.S. newspapers and magazines, and speeches by notable figures—generally favorable to the Service and complimentary of its performance. Except in these official documents and third-party pieces, matters of foreign policy were almost never broached, at least not until the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939. Discussions of fascism or communism were limited to book reviews, of which there were many.

The war pushed civilian diplomacy to the side. Aging under a hiring freeze and unable to operate in combat zones, the Foreign Service spent the war years in a kind of hibernation and the Journal in an editorial torpor (coverage of posts in Latin America, where diplomatic routine was largely maintained, was never again so intense). Only issues of personnel and institutional reform seemed to generate excitement.

Peace and Persecution

Suggestions for Improving the Foreign Service

The Foreign Service is a profession which has been called a science, in that it concerns itself with the observation and classification of facts. It can also be a fine art, when, in intricate international negotiations, great judgment is called into play. Somewhat less pretentiously, it has been thought of simply as a trade. If it is a trade, then words are its tools, and these should be used effectively, as precision instruments. … Young men and women entering a career in which shades of meaning can disturb or strengthen the relationships among nations should be aware of this fact. They should be indoctrinated in semantics and gain reverence for precision in speech and writing.

—James Orr Denby, from his winning entry in AFSA's 1944 essay contest, February 1945 FSJ

In March 1944 the Journal woke up its audience with a contest that offered a donated top prize of $500 (about $7,000 today) for the best essay by an active-duty officer on the topic “Suggestions for Improving the Foreign Service and Its Administration to Meet Its War and Post-War Responsibilities.” (George V. Allen, then a vice consul but later National Security Adviser to President Ronald Reagan, had won a similar but even more lucrative contest in 1935.) Sixty officers—an extraordinary number—submitted essays to a panel of judges that included two serving members of Congress and Under Secretary of State Joseph Grew, the highest-ranking career Foreign Service officer at the time. The winning essay, by James Orr Denby, appeared in the February 1945 Journal (see excerpt). In correspondence published in the March 1945 FSJ, Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius Jr. thanked the Journal and the writers, assuring them that the essays were being studied by policymakers.

The essays were a source of creative thinking in development of the Foreign Service Act of 1946, which provided career status and better pay for Foreign Service staff (today’s specialists), opened a path to career status for the temporary hires of the wartime Foreign Service Auxiliary and created the framework for rapid expansion of the Service, to 8,000 members in 1950.

Passage of the 1946 Act was a high point for the Foreign Service, which for a brief moment had the attention and support of both Congress and the White House. But signs of trouble were already evident. Attacks on Foreign Service officers in China as communist sympathizers had begun in 1945 and would soon metastasize. By 1950 Senator Joe McCarthy (R-Wis.) had charged that the State Department was “infested with communists.” Between 1945 and 1953, hundreds of State Department employees were fired as security risks, as John W. Ford recalled in a November 1980 FSJ article, “The McCarthy Years Inside the Department of State.”

Members of the Foreign Service felt constant pressure to ensure that their reporting from the field validated official thinking, or at least posed no challenge to it. The Journal courageously addressed the issue in July 1951, in an unsigned editorial titled “Career vs. Conscience.” The FSO, the Journal wrote, “finds that a calling which has claimed his abiding loyalty, and his unexpressed but deep devotion to his country, is being assailed and degraded by irresponsible demagogues. …The choice is before him. Shall he remain in the Service, resolved to report only what will harmonize with the temper of the times? Shall he report honestly and fearlessly… knowing the dangers of honesty and the risk to his career and his reputation? Or shall he resign?”

That editorial was a high point. Two years later, the editorial page carried a “declaration of purposes and principles” approved by AFSA and its board of directors that was so bland and bromidic that its authors called it no more than “an initial step in formulating a forthright and vigorous expression of what the Service stands for.” What the Foreign Service stands for has been addressed over and over again in the pages of the FSJ ever since, with mixed results.

Passage of the 1946 Act was a high point for the Foreign Service. But signs of trouble were already evident. Attacks on FSOs in China as communist sympathizers had begun...

After the declaration, the threat of politically directed reporting received far less attention in the Journal than the threat of “amalgamation,” the term used to describe the merger, proposed by a series of blue-ribbon commissions, of the department’s Civil Service and Foreign Service employees into a single personnel system. In its April 1951 editorial, “The Directive to Unify,” the Journal offered limp support for the idea—so long as its implementation was “gradual” and “partial” and did not coerce employees into “careers which did not appeal to them.”

When the department brought some 1,400 civil servants into the Foreign Service in 1954, the AFSA board, at the department’s request, refused to allow the Journal to publish negative comments and instructed the editors to turn over to the department any letters it received that expressed “anxieties” about the program. The AFSA board, which consulted closely with the department’s management, extended its control over editorial content throughout the decade, requiring the Journal to consult before publishing “material of major importance.”

Dissent and Change

In the early 1960s, the Journal, like the country, pushed back against censorious conformity. “The Foreign Service has special reason to be thankful,” said an April 1961 editorial, “for President Kennedy’s statement … that the new administration ‘recognizes the value of daring and dissent’ among public servants. …To our readers, we say: Speak up!”

Speak up they did, softly at first, and then with force and volume. In 1963 AFSA set up a Committee on Public Relations and became far more transparent. The Journal began to publish detailed news about the association, including full or summarized minutes of meetings of the board of directors, as a regular feature. AFSA’s president, Deputy Under Secretary for Political Affairs U. Alexis Johnson, placed a “Dear Colleague” letter, the predecessor of today’s “President’s Views” column, in the Journal’s March 1966 edition. Articles on current topics in foreign affairs and diplomatic practice began to appear with greater frequency—in January 1965, for example, the Journal carried a long and thoughtful piece, “Vietnam: The War That Is Not a War,” along with a story on the aftermath of a Vietcong raid on a village in the Mekong Delta and a report on USIA’s field work in Laos.

Demands for changes in the management of the Service and its treatment by the department took on growing importance, with the Journal serving as a primary link between reformers in Washington and Service members in the field.

The pace of change accelerated as the decade advanced. In 1967 a slate of reformers—the “Young Turks,” led by Lannon Walker and Charlie Bray—won every seat on AFSA’s board of directors. The reformers deliberately ran a stealth campaign, rallying support in missions around the world through private communications, without using the Journal. As soon as they had won, however, they turned to the Journal to promote their program—a program of institutional change, developed in great detail, that would recognize the professionalism of the career Foreign Service and raise the level of responsibility entrusted to it. With a grant from John D. Rockefeller III, they had the Journal publish their proposals in a 128-page report called “Toward a Modern Diplomacy” (November 1969 FSJ, Part Two).

The ambitious reforms that they proposed never came to pass, but the drafting of the manifesto (as the report came to be called) engaged scores of Foreign Service officers in rigorous thinking about the Service as an institution, a profession and a career. As these officers considered their situation, they became less deferential and more adversarial. The idea that members of the Foreign Service were labor and the upper levels of the department were management moved from the periphery toward the center of thinking of AFSA’s officers and directors. In editorials like “A Professional Association” (November 1970), the Journal offered full-throated support for recognition of AFSA as the exclusive labor-management representative—the union—for members of the Foreign Service. The Journal distributed ballots for the many elections that addressed the issue and celebrated AFSA’s victories in its pages.

The Journal and the Union

The collective bargaining agreements between AFSA and the Department of State that followed unionization in 1974 gave AFSA access to State’s communications systems for certain messages on union business, reducing the association’s reliance on the Journal to communicate with its membership around the world. At the same time, the Journal’s “AFSA News” section, which had been just a page or two, grew in scope and took on an identity of its own.

Beginning in September 1975, the Journal’s editors felt it wise to inform readers: “While the Editorial Board of the Journal is responsible for its general content, statements concerning the policy and administration of AFSA as employee representative … on the editorial page and in the AFSA News, and all communications relating to these, are the responsibility of the AFSA Governing Board.”

In the run-up to passage of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, the Journal’s role was subdued. There were no essay contests or efforts to engage the readership in development of new Foreign Service structures, as there had been during the drafting of the Act of 1946. Newly empowered to speak for the Service, AFSA instead met directly with its constituents in Washington and used its own channels to survey its members in the field.

The changing nature of AFSA’s relationship with its members, and with management in the Department of State and other agencies, brought changes in the Journal, as well. The Journal began to shift the balance in its content, leaving AFSA’s union issues to the AFSA News section and devoting more attention to such topics as professionalism, diplomatic history and practice, dissent, diplomacy and the military, security and terrorism, the role of the Service in policy formation and the unfortunate popular image of the career diplomat.

Discussions of these and similar perennial questions filled the pages of the Journal in the 1980s and 1990s. Active-duty and retired members of the Foreign Service contributed most of the material, but civil servants, academics, journalists and politicians wrote for the magazine, as well. “The Journal took on a more journalistic tone,” said Managing Editor Nancy Johnson in “A Stroll Through 75 Years of the Journal” in the May 1994 FSJ.

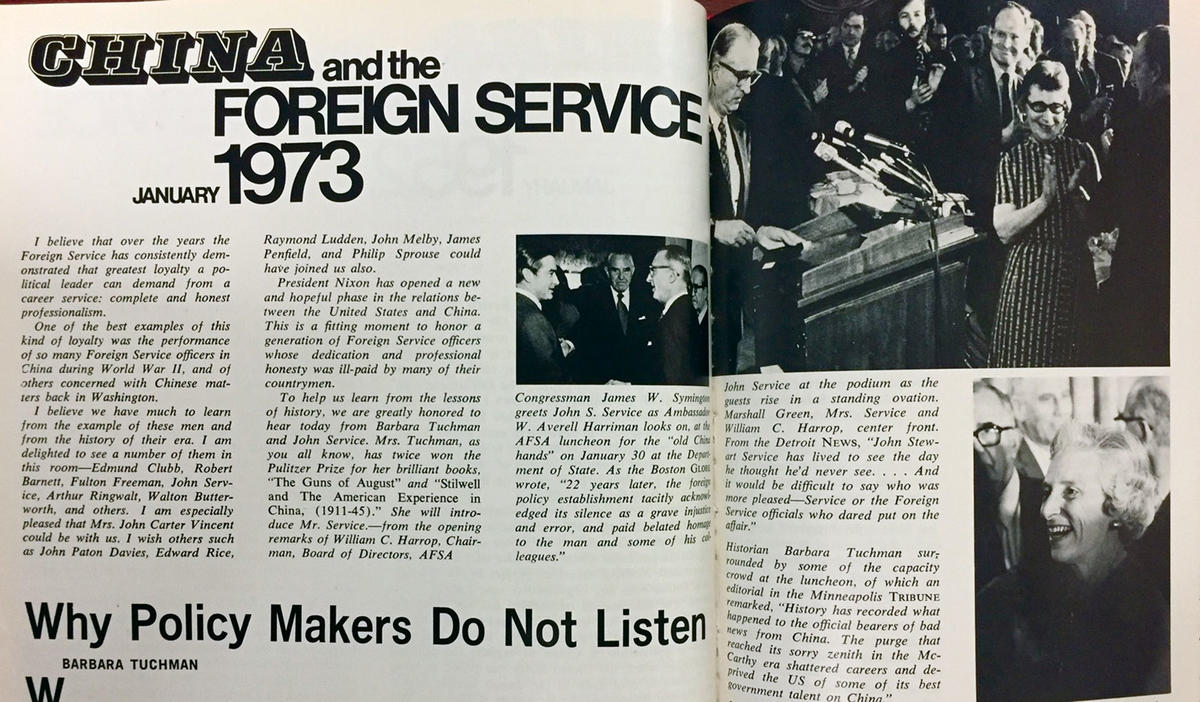

AFSA honored the Foreign Service “China hands” at a luncheon at the State Department on Jan. 30, 1973. AFSA Board Chairman William C. Harrop gave opening remarks. Historian Barbara Tuchman, shown at right, introduced FSO John S. Service, shown above at the podium. Coverage of the event, including Service’s talk on “Foreign Service Reporting,” appeared in the March 1973 FSJ.

Defending the Profession

A reader of the Journal during those years would have been struck by its introspection and defensiveness. Most issues, it seemed, carried some material deploring the sorry state of the Service, suggesting improvements in the institution and appealing for measures to repair the lack of funding, the lack of training and especially the lack of understanding of its work, its efforts and its character by Congress and the public at large. The Journal defended professionalism and the career principle with a wealth of anecdote, but it preached only to the converted: circulation in 1989 averaged about 11,200 per issue, including copies sent to more than 9,200 members of AFSA. Readership outside the Service itself was small, and outside the foreign affairs community it was essentially nil.

At least five editorials defending the professionalism of career practitioners appeared in the 1980s, as well as a cover story (April 1982) and a long—and to this reader, fairly timid—essay by Ambassador Nathaniel Davis (March 1980). Three articles in 1986, by Ambassadors David Newsom, John Maresca and Leon Poullada, discussed the cultivation of leadership and expertise in the Service, with a generally pessimistic conclusion. AFSA President Perry Shankle worried in November 1987 that due to budget cuts, “we must fear for the very survival of our profession.” In March 1989 Newsom, a former under secretary for political affairs, felt it necessary to ask, “Are Diplomats Patriotic?”

In time this gloomy cycle ran its course. In January 1990, on the occasion of the bicentennial of the Department of State, the Journal published a special supplement meant “to increase public understanding and support” and “contribute to the sense of common purpose and dedication among those Americans who devote their lives to the diplomatic profession.” A richly illustrated 32-page AFSA booklet designed to reach an audience beyond subscribers to the Journal, “American Diplomacy and the Foreign Service,” was relentlessly upbeat. By May 1991, in the wake of the Persian Gulf War, AFSA President Ted Wilkinson’s column, “The State of the Service,” spoke of “higher morale.”

The Journal adopted the slogan “The Independent Voice of the Foreign Service” in 1984.

Focus

In the 1990s the Journal began to identify a theme or “focus” for each issue, a topic treated in at least two and usually three or four articles. Initially, matters of foreign policy dominated the coverage: U.S.-Japan, Central America and Cuba, U.S.-Russia, trade policy, human rights and foreign aid were focus topics in 1991 and 1992. As the decade wore on, although issues of foreign policy continued to receive attention, professional and career issues again grew in importance: Focus topics included doing less with less, Foreign Service training, ethics and statecraft, retirement, reorganization, dissent, integration of the U.S. Information Agency into the State Department, diplomacy and the military, dealing with Congress and the Foreign Service as a career.

In particular, the Journal gave great attention to the efforts of Senator Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) to reorganize the Department of State and reshape the Foreign Service. Helms was a narrow-minded conservative with a sure grasp of the power that Senate traditions provided to individual members. When the 1994 elections gave the Republicans control of the Senate, Helms replaced Senator Claiborne Pell (D-R.I.), a former Foreign Service officer, as chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations. The change was a shock to the system. Helms used his position to block Senate consideration of dozens of career nominees thought to support policies that he and his hardline staff opposed. The department never figured out how to deal with him.

The Journal found him fascinating. Helms was the subject of two cover caricatures, one in October 1981 and another in May 1995. His name appeared in 67 of 117 issues during the 1990s. He was the subject of eight different articles, three editorials and scores of letters to the editor (including one he wrote himself, in the May 1995 FSJ). His reorganization plans, which resulted in the closure of USIA and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, received far more coverage in the 1990s than the plans for a new Foreign Service act did in the 1970s. As newspapers and novelists have always known, nastiness sells.

“What This Journal Is All About…”

The Journal adopted the slogan “The Independent Voice of the Foreign Service” in 1984, and kept it on the masthead for the next 10 years (its replacement: “The Magazine for Foreign Affairs Professionals”). The slogan raised the question, independent of whom? Karen Krebsbach, the Journal’s editor from 1994 to 1997, took an expansive view. Krebsbach, who left the Journal after repeated fights with, in her words, “[AFSA] Governing Board members who believe that only positive pieces about the Foreign Service should be published,” wrote in her December 1997 farewell, “Swan Song from a Lame Duck,” that the Journal “should not be the voice of the State Department, the voice of the Governing Board, the voice of the Editorial Board. It is the voice of the Foreign Service, the voice of its readers.”

AFSA President Marshall Adair agreed. “The Journal,” he wrote in a president’s column in March 2000, “is charged with two responsibilities: Communicating AFSA news and views to the membership, and serving as a forum for lively debate on relevant issues of foreign policy. Of the two, I believe the second is by far the most important. … While [the Journal] is owned and supported by AFSA, it cannot be a company magazine.” Disagreements between AFSA’s Governing Board and the Journal’s Editorial Board, he said, are “natural and healthy.”

But the Journal was (and is) AFSA’s publication. The Governing Board has ultimate responsibility for, and therefore must have ultimate authority over, the Journal’s contents. AFSA relies on the Journal’s Editorial Board to give final approval to articles for publication, and the Journal’s paid staff—paid by AFSA—handles the day-to-day work, including the editorial, production and business sides of the publication.

In 2001, when the AFSA Governing Board (led by Adair’s successor, John K. Naland) directed the Journal to survey its readership, a strong majority of respondents wanted the magazine to devote more space to “professional/personnel/lifestyle issues.” The board instructed the Journal to follow that guidance.

The AFSA board also told the Journal to cut expenses. AFSA’s accounting showed losses for the Journal rising from around $60,000 in 1994 to $220,000 in 2000. (AFSA’s accounting gave the Journal no budget-line credit for the portion of members’ dues that paid for their subscriptions, inflating a deficit that may not have existed at all.) By mid-2001, Journal editor Bob Guldin, Karen Krebsbach’s successor, had resigned. AFSA moved the Journal’s associate editor, former Foreign Service Officer Steven Alan Honley, into the top spot.

Honley remained as editor until 2014. Early on, he made changes to freshen the publication and strengthen its engagement with its readers. He wrote an occasional “letter from the editor” to solicit contributions and feedback, and he published a calendar of topics on which the Journal intended to focus a year in advance. He used online surveys to track and generate reader interest—a survey on best and worst posts elicited 1,300 responses.

Senior Editor Susan Maitra and Associate Editor and former FSO Shawn Dorman became frequent contributors to the Journal, and Honley wrote often for its pages himself. Dorman produced in-depth articles looking at issues of the day, soliciting input from the active-duty Service and thus capturing views not otherwise obvious. The topics included reform at State, Iraq War service (one of which was reprinted in The Washington Post) and transformational diplomacy.

The Iraq War coverage won the Journal praise from the Columbia Journalism Review in 2007.

Honley experimented with new features like a personal finance column that responded to questions from readers; and when that flagged, he broadened it to “FS Know-How,” publishing readers’ thoughts about dealing with a range of issues peculiar to Foreign Service life. The “Clippings” section, which published excerpts of interest from the general press (as the Journal had done from its earliest days), became Cybernotes, to bring in material found on the internet. He also introduced “FS Heritage,” a space for occasional reader-driven vignettes from the Service’s past. (According to the March 2015 FSJ, Fiorello LaGuardia was a consul in Fiume. Who knew?)

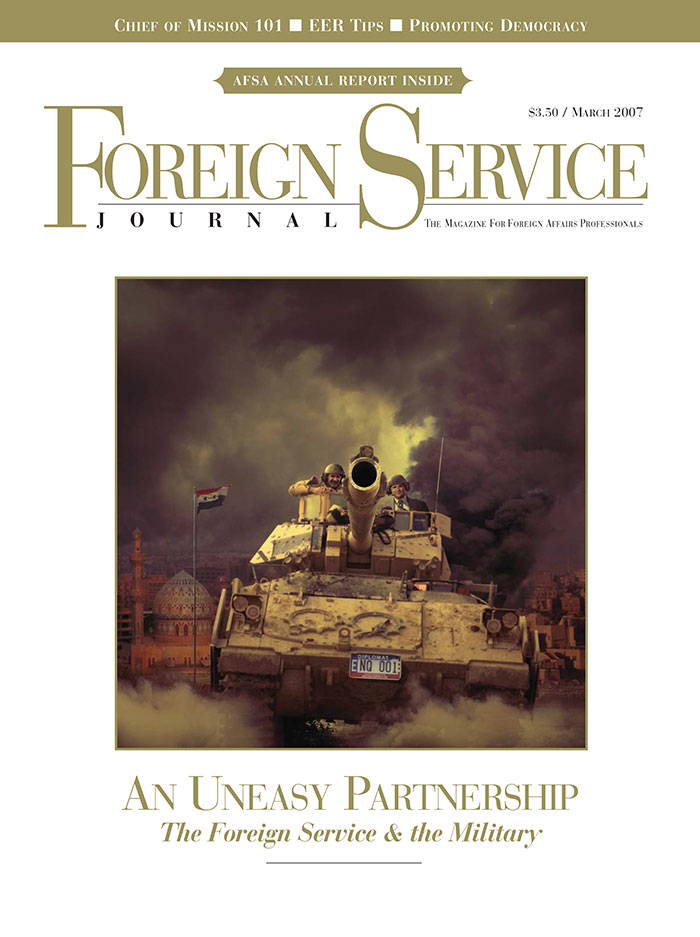

The Journal’s balance of content shifted perceptibly to conform more closely to readers’ interests. Not that foreign policy issues were neglected—several issues each year were devoted to a region or country (e.g., India, China, Russia, the Arab Spring, the Euro Zone, Latin America) or to a general topic (e.g., global energy, climate change, political Islam). Notably, the March issue in every year from 2004 through 2008 dealt with Iraq and its consequences for both American policy and the Foreign Service. The Iraq War coverage won the Journal praise from the Columbia Journalism Review in 2007.

During the 2000s the Journal tried to strike a balance in its foreign affairs coverage between articles by active or retired members of the Service and outside experts and notables. The latter included former U.S. presidents Jimmy Carter and George H. W. Bush, former Secretary of State George P. Shultz (twice) and Secretary of State Colin Powell. In 2012 the Journal underwent a redesign, the first major change in layout and typeface since 1994. The redesign offered more flexibility in the design and cover images and gave the Journal a contemporary look.

The Journal Today

Shawn Dorman was selected for the editor-in-chief position in late 2013, when Steve Honley stepped down, taking up the post in January 2014. She expanded the occasional letter from the editor into a monthly feature aiming to frame each issue, especially the focus theme of the month. The Journal has continued to take on sensitive topics of concern to its members. With the demise of the Secretary’s Open Forum (born in 1967, abandoned and left for dead around 2002), the Journal in many cases serves as the only space for public discussion within the Service of such issues as expeditionary diplomacy (September 2011), managing risk and security after Benghazi (May 2015) or the militarization of diplomacy (June 2017).

In Dorman’s words, the Journal “aims to shine a light where light is needed.” The Journal, she says, “occupies a unique space as the publication that puts a Foreign Service and diplomacy lens on the issues of the day.” She sees the magazine as a vehicle for sparking discussion and debate about the role of diplomacy and development, and, when possible, advancing the conversation inside and outside the Service.

In 2015 the AFSA Governing Board affirmed the Journal’s editorial independence, although no serious disagreements have emerged since then to put the proposition to the test. On the contrary: if AFSA is the voice of the Foreign Service, the Journal has been its megaphone. AFSA President Barbara Stephenson used her December 2017 “President’s Views” column to call attention to the erosion of the senior ranks of the Foreign Service and to ask, “Where is the mandate to pull the Foreign Service team from the field and forfeit the game to our adversaries?”

A word of warning: poking around in the archive will stir the sediment of memory in ways that are informative, revelatory, provocative and habit-forming.

The column, released before its official publication, was widely read and quoted, revealing a depth of congressional and public support for diplomacy and the career Foreign Service that few knew or believed existed. Representative Tim Walz (D-Minn.) cited it in a piece he wrote for the January-February 2018 Journal, “Dear Foreign Service: We’ve Got Your Back.” Walz’s message was the first of a planned series from members of Congress, whose bylines had been almost wholly absent from the Journal since 2000. In March, Senator Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) offered his “Message from the Hill,” calling for a national conversation about the role of the United States in the world.

In 2017 AFSA completed the digitization of the Journal’s back issues, from March 1919 on, all of which are now available in a searchable archive at www.afsa.org/fsj-archive. Making this trove accessible to researchers, policy professionals and the public will help to dispel the widespread ignorance and misunderstanding of the U.S. Foreign Service and what it does. But Foreign Service people should take a word of warning from the writer of this article: Poking around in the archive will stir the sediment of memory in ways that are informative, revelatory, provocative and habit-forming.

Today The Foreign Service Journal has a print circulation of about 18,000 copies, and a digital edition, accessible without subscription on the AFSA website, that is widely viewed and shared.

Coda

A century is a long, long run for a magazine. Collier’s didn’t make it, nor did Life, McCall’s or The Saturday Evening Post. The Foreign Service Journal, however, remains what its consular progenitors wanted it to be: a source of group cohesion and spirit, a guide to best practices, intellectual stimulation and debate, and a beacon of excellence and professionalism across the Foreign Service.

The Journal faces the challenges that afflict many print periodicals: high costs, a scramble for advertising revenue, and conflict between an internet that demands speed and a product that demands deliberation. The Journal is fortunate, however, to have readers who care about and contribute to its content. If the readership stays engaged, the Journal will be with us into the 22nd century.