Lethal Encounter in Tehran: The Attack on U.S. Vice Consul Robert W. Imbrie and Its Aftermath

Almost a century ago, an American diplomat died overseas at the hands of a mob. The implications of this tragic incident reached far beyond Iran’s capital city.

BY MICHAEL ZIRINSKY

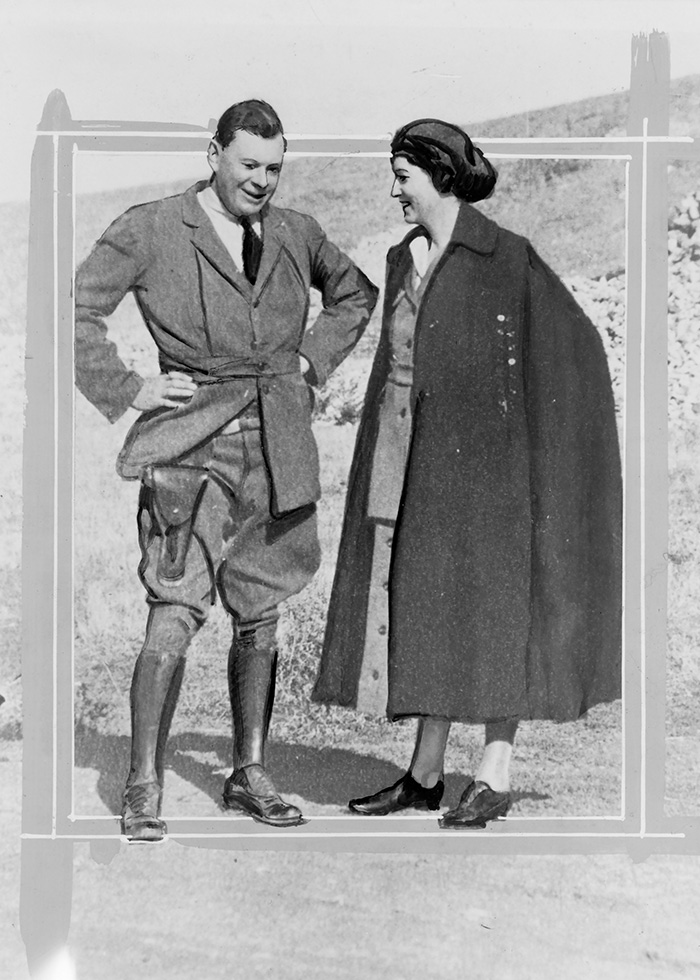

On an inspection tour in Tehran in 1924, U.S. Vice Consul Robert W. Imbrie (at left) poses in front of a vehicle with a staff member and local aides.

U.S. Library of Congress

On Friday, June 22, 1956, my suburban New York family arrived in Tehran. The next day my father began his Cold War job as counsel to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Gulf District supervising construction contracts for Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. In September I began ninth grade at the American Presbyterian Mission’s Community School. Soon afterward, an uncle sent me his old Rolleiflex camera, a present for my 14th birthday. As I readied it for use, my parents warned me strongly, “Do not take pictures in public!” They had heard that an American diplomat had been killed years earlier for doing so.

Fast forward to 1979: The Iranian Revolution found me in Idaho, a newly minted Ph.D. teaching modern European and Middle Eastern history at Boise State. Although I had been trained as a Europeanist, the revolution provoked me to investigate U.S.-Iran relations. I arrived at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 26, 1981. That day I was attracted by a strange entry in the 1939 Foreign Relations of the United States regarding the killing in Tehran on July 18, 1924, of Vice Consul Robert W. Imbrie—that same diplomat. The Iranian government had objected to publication of some relevant documents, so “the Department reluctantly reached the conclusion that it would be best to defer publication [on Imbrie] until such time as the Iranian Government was in a position to give its consent.” (The department has never published the documents in FRUS.)

Undeterred, I started with Imbrie’s personnel file. There I discovered that one of the many explanations suggested for his murder was that the crowd that beat him to death objected to his photographing a religious “shrine.” The archivists also pointed me to the Dulles papers at Princeton University and the Presbyterian archives in Philadelphia. Allen Dulles was chief of the State Department Near Eastern Affairs Division in 1924, and most Americans in Iran then were Presbyterian missionaries who for decades had operated schools and hospitals throughout northern Iran.

The next day, as I began to connect this episode with my parents’ warning, I became aware of an exodus from the archives. The U.S. Embassy Tehran hostages were on their way from Andrews Air Force Base to the White House! I joined the crowd on Pennsylvania Avenue. While we waited, a rumor swept through the throng: The buses were coming from the east, in the far lanes. As one, we flooded the near lanes, despite horrified efforts by police to keep us on the sidewalk. We all cheered the heroes of our national humiliation, then returned to work. But as I contemplated the Tehran crowd of July 1924, I realized I had just received a lesson: A crowd is more than a group of individuals. It can—as had the Paris crowd of July 14, 1789, and as had the crowd that killed Imbrie—take on a life of its own and do what no individual intends to do.

On That Friday in July 1924

A portrait of Robert W. Imbrie, 1924.

U.S. Library of Congress

The bare outline of what happened that Friday in July 1924 seems clear. One of the nodes of anti-Baha’i violence, rife in Tehran that summer, was a saqqa-khaneh, a “fountain” where a Baha’i was said to have been struck blind when he failed to bless the Shia saints, then had his sight restored when he did so. Imbrie, accompanied by Melvin Seymour—an oilfield roughneck serving a one-year sentence in the consular prison for assaulting another American oil worker with a baseball bat—approached the fountain with a camera.

Imbrie seems to have anticipated violence because he had armed his prisoner with a blackjack. Someone called out “Baha’is!” and the crowd attacked. Imbrie and Seymour ran away. They were caught and beaten. Extricated by the police, they were taken to a police hospital for treatment. There they were attacked again, the crowd augmented by soldiers from Reza Khan’s army whose barracks were nearby. Imbrie died of his wounds, including a saber slash to his head. Mrs. Imbrie believed Seymour survived because attackers relented at the sight of his naked body: “Certain physical appearances gave evidence that Seymour might be a Mohammedan.”

I published my conclusions in the August 1986 issue of the International Journal of Middle East Studies, connecting the incident both to international and Iranian domestic contexts. In the international context, Britain was attempting to dominate Iran in order to stabilize the borders of its Indian empire and its new mandate for Iraq, as well as to secure control of Iranian oilfields. The Anglo-Russian “Great Game in Asia” continued in Iran in the 1920s, although the terminology had become that of the “Cold War.”

Britain failed to make Iran a “colony by treaty” with the abortive 1919 Anglo-Persian Agreement, despite paying members of the Iranian government to ensure ratification. Subsequently, British officials in Iran encouraged Cossack General Reza Khan to seize power in Tehran in early 1921, to forestall a feared Soviet incursion after Britain withdrew its army from Iran in the spring.

Anglo-American rivalry also continued in Iran, especially over oil. In 1914 Winston Churchill had bought a controlling interest in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now BP) in order to end the Royal Navy’s dependence on American oil. A decade later Foreign Secretary George Curzon expressed Britain’s continuing intent to keep American “fingers” out of Britain’s “oil can,” opposing Iran’s efforts to grant an oil concession to an American-owned company.

A crowd is more than a group of individuals. It can take on a life of its own and do what no individual intends to do.

In the Iranian domestic context, Reza Khan sought to curb independent tribal forces and the domination of cities by local bazaar merchants and their clerical allies by establishing a military dictatorship over the entire country. He supported the American financial mission Iran had hired in 1922 in an effort to break dependence on British subsidies. In March 1924, Reza sought to end the Qajar monarchy and make himself president of a republic, as Mustafa Kemal had recently done in Turkey.

Popular opposition to Reza’s proposed republican dictatorship was mobilized by Shia clergy, both in the Majlis and in the streets. In the Majlis, Ayatollah Sayyid Hassan Modarres led the resistance, arguing: “The source of our politics is our religion.” During World War I, Modarres had been a member of the Ottoman-supported Nationalist government, opposing Russia and Britain, and in 1919 he had helped lead opposition to the Anglo-Persian Agreement. Other clerics in Tehran mobilized a crowd of demonstrators, who were attacked in the Majlis garden on March 22 by two regiments of Reza’s Cossacks.

The Majlis refused to pass the bill. Reza was believed to be ready to flee the country; instead, he recovered by paying obeisance to the ulama, going to Qom and promising Ayatollahs Hairi, Naini and Isfahani that he would never make a republic. Whether explicit or tacit, he also seems to have given free rein to the clergy to organize anti-Baha’i violence.

So Who Was Robert Imbrie?

U.S. Vice Consul Robert W. Imbrie and his wife, Katherine, in 1924.

U.S. Library of Congress

Why was Imbrie in Tehran? He was no diplomat. “Adventurer-spy” is a better description. Bored with the practice of law in Baltimore, he had joined an expedition to the Congo in 1911. When war began in Europe in 1914, he volunteered for the French Army, serving as an ambulance driver at Verdun and Salonika. In 1918 he published an account of his adventures, Behind the Wheel of a War Ambulance.

When the U.S. joined the war in 1917, Imbrie entered the Foreign Service and was sent as a special consular agent to Petrograd, where he repeatedly clashed with Bolsheviks. Expelled from Soviet territory, he moved to Viborg, Finland, running agents into Soviet Russia until June 1920. Subsequently, he was sent to Istanbul to work with Pyotr Wrangel’s White army in the Crimea, but Wrangel was defeated before he arrived.

In Istanbul he became friendly with young Allen Dulles, then deputy to American High Commissioner Admiral Mark Bristol. Dulles seems to have been instrumental in assigning Imbrie to Ankara, where he opened American relations with the Kemalists and facilitated Admiral Chester’s efforts to obtain an American mining and oil concession in Anatolia. In October 1924, The National Geographic Magazine posthumously published Imbrie’s adventure tale, “Crossing Asia Minor, the Country of the New Turkish Republic.”

Imbrie was recalled to Washington in July 1923 to answer charges that his friendship with Turks had endangered the lives of Greeks and Armenians. He was also accused of calling Louise Bryant, the widow of John Reed and pregnant fiancée of William Bullitt, a Bolshevik. After clearing Imbrie of the charges, Dulles, by this time chief of the Near Eastern Affairs Division at State, assigned him to the consulate at Tabriz, again to spy on Soviet Russia and to facilitate the American oil concession for northern Iran that Tehran had offered as collateral for an American loan.

Dulles knew he was gambling, writing on Sept. 19, 1923, that “in sending a man of Imbrie’s impetuous disposition to far away countries we are taking a certain risk. ... The only question is whether the advantages ... justify this risk. I am rather inclined to think they would.” In Iran, Imbrie was temporarily assigned to the Tehran consulate.

Why did Imbrie go to the saqqa-khaneh? He had recently intervened with the Iranian government on behalf of American Baha’is, Dr. Susan Moody and her nurse Elizabeth Stewart, so his curiosity was understandable. He was also a freelance writer and photographer. In retrospect, his investigation appears to have been insufficiently cautious, perhaps because of his ignorance of the domestic political situation on that day of public prayer, shortly before the onset of Muharram, a time of public mourning for the martyrdom of Imam Hussein and of ritual cursing of foreign enemies: Sunnis, Arabs, Turks and—more recently—Western imperialists.

A headline captures the news of Robert W. Imbrie the day after his death, on July 19, 1924.

Reno Gazette-Journal

The U.S. Reaction to Imbrie’s Death

As I reconsider this episode in U.S.-Iranian relations, what strikes me most sharply is the ignorant arrogance of American reaction. The press, whose information came primarily from U.S. government sources, regarded the murder as the result of religious fanaticism. Or perhaps it was “a Bolshevik mob,” as a Chicago Tribune report from Istanbul put it, alleging that Imbrie had been on a “Bolshevik death list for six years.”

The prejudice, racism and violence of the American government response to the murder were appalling. The U.S. demanded justice, but official documents suggest “justice” was a euphemism for “revenge.” Reza’s army held a court-martial for supposed rioters. The U.S. believed the process was a sham, and Chargé d’Affaires Wallace Murray protested strongly to the Iranian foreign minister. Murray wrote, “The Persian is venal. His promises and lip service can be bought for a song.”

Eventually the court delivered 20 guilty verdicts and death sentences for three teenage scapegoats. One, 19-year-old Cossack Private Morteza, was executed for disobeying orders, not for murder. Death sentences for 14-year-old camel-driver Ali Rashti and 17-year-old “mullah” Sayyid Husain were commuted to life imprisonment. On learning of the commutations, Dulles exploded in anger to the Iranian chargé. The Iranian government reinstated the death sentences. American Chargé Murray refused pleas for mercy, and the executions were carried out in the presence of a U.S. representative, chief legation translator Allahyar Saleh. Saleh, who had been educated by American Presbyterian missionaries, went on to become Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh’s ambassador to the United States in the early 1950s and, afterward, leader of National Front opposition to the shah’s dictatorship.

An unsigned NEA memorandum, which I believe to have been written by Dulles, presented the old cliché, “human life as such is not greatly valued by Orientals,” as justification for seeking blood. Dulles later testified to Congress, “When you are dealing with a government like Persia ... if you ask them to execute a Moslem for the death of a Christian ... if they do it, you accomplish more for the prestige of your country than if they paid a million.” The U.S. also insisted Iran pay compensation. Mrs. Imbrie received $60,000. Seymour received $3,000. The U.S. government received $110,000 for expenses incurred transporting Imbrie’s body by warship from Iran to Washington, for interment at Arlington National Cemetery. Given Iran’s poverty and the dollar’s purchasing power at that time, these were enormous sums.

The Broader Implications of Imbrie’s Death

Widow of Robert W. Imbrie, Katherine Imbrie, at the U.S. Capitol. She would appear before the House of Representatives Foreign Relations Committee, asking for an additional allowance for his death.

U.S. Library of Congress

Reza Khan used the incident to rally support for his military dictatorship. Whether or not there was any substance to the rumor that he sought the death of a foreigner to justify imposition of martial law, he made clear to the legations that their choice was either to face continuing clerical-led riotous unrest or to support his new military order. As U.S. Minister Joseph Kornfeld put it, “Whatever justice we obtain must come from [Reza] through his military courts,” the alternative being, in Chargé Murray’s words, fanaticism led by the “senile old man” Hassan Modarres.

In this, Murray echoed British Chargé Esmond Ovey who regarded Modarres as “a bigoted and unwashed Sayyid, the Diogenes of the Majlis, who lives in a hovel and ostentatiously refuses money for himself.” This description of Modarres entirely ignores the cultural context, in which living modestly is both a sign of piety and the Iranian political equivalent of corporate lawyer Abraham Lincoln campaigning as a “rail-splitter born in a log cabin.” Not to mention that Modarres’s ostentatious refusal to accept bribes was an implicit criticism of those who accepted foreign subsidies.

The episode moved American policy into line with that of Britain. Before the murder, the British legation regarded the Americans as hostile, writing that Murray “hardly takes the trouble to conceal his Anglophobia,” and worrying that independent American policy might give Iran “another fatal chance of playing off one Great Power against another.” British Minister Percy Loraine feared that “Anglo-American rivalry destroys [the] last hope of salvation.” After Imbrie’s death, America approved Reza’s “desire to create a disciplined armed force ... and not to be the commander of a horde of tribesmen.” In London, the Foreign Office crowed: “America is being educated in Eastern matters—which is to the good—especially as regards ourselves.”

The result of all this was Reza’s ability, with the support of foreign legations, to make himself the Shah of Iran. In parliament, Mossadegh—who had served Reza as minister of finance and as a provincial governor—argued that while Reza had done brilliant service to the nation as war minister and prime minister, if he were king, he would no longer be responsible to the Majlis. Only three other parliamentarians joined him to vote no. Unchecked henceforth by the Majlis, Reza Shah proceeded forcibly to create the modern Iranian state, eliminating opposition—real or imagined—by violence.

Ayatollah Sayyid Hassan Modarres was among Reza’s many victims. Surviving a 1926 assassination attempt, he was arrested in 1928 and exiled to a small town in Khorasan where in 1937 he was strangled while at prayer.

By the late 1930s, the British Foreign Office came to view Reza Shah as “a dull savage of the sergeant-major type,” pro-German and a “bloodthirsty lunatic.” The U.S. legation concurred, Minister William Hornibrook fearing that Reza Shah’s “wholesale introduction of European customs, his hostility to the clergy, his ruthless methods and his success in inculcating ... ultra-nationalistic feelings may possibly result in a bitter anti-foreign feeling in the event of his demise.”

Ironies happen. “Modarres” means “teacher,” and Sayyid Hassan was dubbed Modarres long before he achieved the clerical rank of ayatollah. Among the students influenced by his personal modesty and outspoken political views was Ayatollah Hairi’s student, young Ruhollah Khomeini. The Islamic Republic regards Modarres as a shahid (martyr), and his image was placed on Iranian currency where the shahs’ faces had once loomed. My high school, formerly the hospital where Imbrie’s autopsy was conducted, is now Shahid Modarres High School. So it goes.

Read More...

- On Distant Service: The Life of the First U.S. Foreign Service Officer to be Assassinated, by Susan Stein, Potomac Books, July 2020

- “Love in Tiflis, Death in Tehran: The Tragedy of Alexander Sergeyevich Griboyedov,” by John Limbert, FSJ, October 2017

- “Murder in Tehran,” by Henry S. Villard, FSJ, June 1982

- “The 1979 Hostage Crisis: Down and Out in Tehran,” by Michael Metrinko, FSJ, March 2015