Setting Sail: Life after USAID

Short-term consulting gigs with USAID made for a gratifying transition to full retirement for this FSO.

BY CHARLES LLEWELLYN

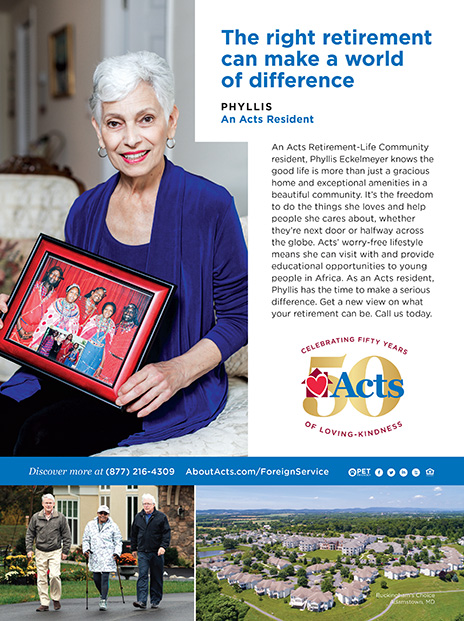

Llewellyn’s retirement office, November 2021.

Courtesy of Charles Llewellyn

One of the benefits of a career in the U.S. Foreign Service is the possibility of early retirement with a federal pension, allowing one to pursue a second career or latent dreams.

As a USAID health and population officer, I experienced highs and lows. The upside was truly making a difference by working with incredible colleagues to improve the health status of citizens and building the skills of host nationals to develop stronger health systems. There were also trying times working under policies and administrations not in line with my views about development. Sometimes I was tempted to resign in protest, but the threat of losing my pension was enough to nudge my cost-benefit calculation in favor of sticking it out to fight the good fight from within instead of running away.

Let me share my journey.

I joined USAID relatively late, at age 35, and served in five missions in South America, Africa and South Asia. While I loved my job, my last two tours took their toll on my health. I was the director of USAID Bangladesh’s Population, Health and Nutrition Office from 2000 to 2005, including managing the agency’s largest family planning program. I had extended a fifth year to allow my son to graduate from the American International School in Dhaka, and in the last year had the responsibility to report to Congress in 2004 the first-ever violation of the U.S. government’s Mexico City policy that had been reinstated in 2001.

The restriction on U.S. federal funding for NGOs that provide abortion counseling or services made continued support of certain organizations offering family planning in Bangladesh very challenging, but was a part of our job. However, the administration’s response to the notification of the violation was extreme and totally consumed our office for a whole year, causing great stress to the program, our staff and to myself.

My next posting was as director of the Health and Population Office in Tanzania. We had a small $12 million portfolio of child survival and family planning activities because the HIV/AIDS program was managed by a separate office. Between the time I was appointed, and arrived at post in late 2005, it was announced that Tanzania was designated one of the first three President’s Malaria Initiative countries. I had a wonderful time helping to develop that program and was also able to greatly expand the family planning, maternal and child health and other disease portfolios to the point that when I left, the office budget was over $120 million a year, with 20 employees. So my quiet new job became one with giant challenges and responsibilities. Not without stress but with many successes.

I loved the work and the life (I was a sailor and the diving secretary of the Dar es Salaam Yacht Club). But when I mentioned to my wife, Deborah, that we should start looking for another post, she resisted. Deborah was ready to enjoy the North Carolina coastal home we had purchased, spend more time with extended family and launch a few creative endeavors. I was still focused on my international public health career and was not sure what else I could do outside USAID, where I had seniority and stable employment.

I had lots of adventures, and some challenges, but really enjoyed the work, especially mentoring junior officers.

Deborah was also concerned for my health. I was exhausted from the long hours and responsibilities. She argued that I should retire, relax and take on some consulting where I would be paid more, set my own work schedule and have fewer actual responsibilities. After looking at the surprisingly old man in the mirror, I agreed.

In March 2010, at age 60, I took the Foreign Service Career Transition Center Job Search Program (aka Retirement Seminar), which I found very well done and useful. I retired and began collecting my annuity. Rather than starting a second career, I looked to my role model for retirement, USAID Health Officer Sam Haight, who had been my mentor in Ecuador during my Peace Corps service. After his retirement from USAID, Sam worked as a part-time adviser in the USAID Health Office in Peru, where I served in 1986, and for other missions.

I was able to get several short consulting contracts with former institutional contractors (cleared by USAID Legal because I was advising them on general directions in health development and in no way representing them to USAID). For short-term assignments, not reimbursed by the government, they were happy to pay me a generous daily rate, which established my salary history.

From 2010 to 2020, I worked part time with 13 USAID mission health offices under a wide variety of agency hiring mechanisms, including GHPro, Mission Personal Service Contracts, BPA, STAR, the Firehouse and others. I would do almost anything a mission health office wanted me to do, and could put up with nearly anything, anywhere on a short-term basis.

There was a lot of demand for challenging missions like Angola (home of the $250 cheeseburger) and Nigeria (where I would go to and from the airport in an armored vehicle with an armed guard in the front seat, unless they forgot to send someone, in which case I would take a taxi). My wife encouraged me to take one-month assignments, so we could enjoy more retirement time together. So if a mission wanted me for a longer-term assignment, I would negotiate terms like one month on, one month off.

By working half time during this 10-year period, I was able to gradually transition to more typical retirement avocations—woodworking, diving and sailing.

I had lots of adventures, and some challenges, but really enjoyed the work, especially mentoring junior officers. I was recruited to work in Benin and Mali. When I protested that I don’t speak French, the missions said they didn’t care—I spoke USAID-ese, which is all they wanted. Fortunately, the USAID/Benin health office assigned a third-year Peace Corps volunteer to me, so I wouldn’t starve, and we enjoyed zipping around by moto taxi. I also returned to familiar missions, such as Nepal where I was able to save the government housing money by living with my daughter, Bronwyn, who had joined USAID as an FSO when I retired. It was very personally satisfying to help Nepal’s health sector recover from the earthquake in 2015.

Finally, I went to Ghana in January 2020 for the first of two monthlong assignments, but COVID-19 put a stop to that. So I resigned my personal services contract and reentered retirement full time, yet again.

This retirement strategy has worked very well for me. I was able to “keep my hand in” public health on a part-time basis and provide some greatly appreciated support to beleaguered missions based on my 30 years of experience. At age 70, I decided to finally hang it up and leave this work to younger minds and bodies.

By working half time during this 10-year period, I was able to gradually transition to other more typical retirement avocations, such as woodworking, diving and sailing. Indeed, this article is being drafted from a sailboat I am crewing from North Carolina to the Virgin Islands! Consulting allowed me to make a considerable amount of money to finance my retirement, including lots of tax-free per diem and frequent flyer airline mileage. I realize that this lifestyle is not for everyone, but it surely worked for me!

Read More...

- “What Are We Doing Now, Pt. II,” by collected authors, FSJ, July-August 2016

- “Retiring Early and Finding Your ‘Ever After,’” by Dean J. Haas, FSJ, May 2016

- “It Takes a Village,” by Martha Thomas, FSJ, May 2016