Working with the U.S. Military

A retired FSO ambassador offers insights and tips—the real deal—on working with the U.S. military after nearly a decade as a private contractor.

BY LARRY BUTLER

Larry Butler, at right, on a training exercise at Fort Irwin in California in September 2017, roleplaying the head of a small diplomatic mission in a fictitious country, Atropia. Col. Jay Miseli, at left, commander of the 2nd Stryker Combat Brigade, 2nd Division, was charged with defeating an invading enemy force while interacting with the mission and local civilian leaders (also role players).

Courtesy of Larry Butler

Since retiring from the Foreign Service, I spend three to four months a year on the road supporting U.S. military exercises and training events. Ignoring the advice in FSI’s superb Job Search Program to do something unrelated to my former career, I had already set up a part-time position with the State Department Inspector General and had an offer from a former colleague to be a role player and interagency expert for U.S. Army field exercises. I imagined that working episodically and visiting parts of the United States and the world I had never served in would scratch my travel itch and supplement my annuity.

Two years of working on and off for State gave way to working exclusively with the U.S. military. The colleague who first recruited me had set up a company to provide embassy role players (e.g., chief of mission, public affairs, USAID, RSO) to prepare brigade combat teams headed for Iraq and Afghanistan. He knew that I had worked closely with the U.S. military; I had served at embassies dealing with armed conflict (Balkans) and on assignments as a foreign policy adviser (POLAD) to NATO and the U.S. military in Iraq and Germany.

Why role players? Since the State Department rarely can spare an FSO for two to three weeks to support pre-deployment training at the Army’s training centers (including those in Pennsylvania, Louisiana, California, Indiana and Germany), the business opportunity arose for defense contractors to supply those persons. It was a challenge (with mixed outcomes) to find people with real-world and relevant experience prepared to spend considerable periods of time away from home in austere, uncomfortable locations (e.g., exposed to spider bites in Indiana, sweltering in Louisiana’s humidity, and frying while locked in the back of an armored vehicle in the Mojave). But I signed on.

The Exercise Network

A few weeks later, I found myself at Fort Irwin, California. There may be more remote locations in the United States, but this one’s in the top five. For two weeks I was the head of a small diplomatic mission in a fictitious country working with a real Army brigade commander charged with defeating an invading enemy force while interacting with us and local civilian leaders (also role players). Each of the three main Army combat training locations have 10 or more exercises annually, hence the challenge for the many defense contractors to have a bench deep enough to field an adjustable size range of diplomatic missions.

Then I moved up to role-play chief of mission, deputy chief of mission or POLAD for higher-level exercises. There are five of these exercises annually, and they normally occur at the unit’s home post, which may be anywhere from South Korea to Germany or across the United States. Due to my interaction with senior Army commanders and other interagency role-player veterans of these exercises, I started getting requests from other defense contractors to support special operations forces, U.S. Marine Corps and the U.S. Air Force. In the last three, my duties range from providing instruction (Embassy 101) to officers and units getting ready, or having to be ready, to deploy and work with an American embassy, to replicating an actual embassy. Sometimes I go for just two or three days, sometimes up to three weeks. In 2021, I flew more than 50 segments with United Airlines and logged 110 nights in hotels.

One’s reputation combined with effective networking is a force multiplier.

I also support one of the American geographic combatant commands (think CENTCOM, SOUTHCOM, EUCOM or INDOPACOM) for very high-level exercises. Duties start with helping to sketch out the scenario and rollout, and then scripting. We draft authentic-looking embassy cables, news releases and other documents that replicate the environment in which the military has to operate. We are then present when the exercise takes place, sometimes to role-play one of the embassies the military has to deal with, at other times to dynamically replicate the information and message flow as the exercise plays out.

On a separate track, I was also recruited by name as a “highly qualified expert” or senior mentor for a one-week annual planning exercise conducted at the Army War College in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. And West Point invited me to be a co-chair at its annual Student Conference on United States Affairs. Both of these affiliations only lasted for two years, but they were professionally rewarding. I was also asked to serve on a National Defense University workshop examining risks to the Baltics, which led to interactions with the Army’s Foreign Area Officer Association. All of the above helped widen my network and led to new employment opportunities, including a new track to work with NATO.

Semper Gumby!

One thing to consider in working with the military is that it doesn’t last forever, and one must be adaptable. Semper Gumby (Always Flexible) is an unofficial motto in the military. Case in point: I wrote this piece in December 2021. At that time, my work calendar for January through June was packed. Because of Ukraine, nearly every gig was canceled or postponed, a good example of one of my “laws of the Foreign Service”—no job is certain until you get off the airplane.

Contracts end or get modified, senior military leaders move on and new ones have new ideas—and one’s relevance has a sell-by date. The longer you have been retired, the less value you bring. Hence, defense contractors are constantly looking for fresh talent. But the opportunities are many and varied and the networks for accessing them dynamic.

Rounding out my experience have been requests from various military publications to author book reviews, articles or opinion pieces, or deliver a lecture. Some are compensated, most not. In early December, I was invited to be a panelist (on Zoom) for one of the Joint Special Operations University’s quarterly forums to provide a State Department perspective. Based on that, I am also working with that organization on another project tied to one of my prior assignments.

Other opportunities exist in the arena of working with, or on behalf of, the U.S. military in a full-time capacity. I have referred a dozen retired colleagues for full-time jobs in the Balkans and Middle East to support security force assistance programs funded by both State and the Department of Defense. There are also positions on faculty for the senior defense service schools (National Defense University cluster, and the Army, Navy, Air Force War Colleges) and the Marshall Center in Garmisch, Germany, as well as civilian employee positions at the major commands that have foreign policy adviser shops.

Prior experience is critical here, but there are fewer opportunities today in part because not so many U.S. Army units are in combat zones. This, and other factors, has led to State dialing back the number of FSOs assigned as POLADs since 2013, when the number of FSOs on DoD exchange peaked at about 85, up from 35 to 40 in 2000. This reflected both the ending of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the strain on the Service to provide qualified people. (Sometimes qualified people were sent to places where they were not being used; sometimes they weren’t qualified to do the job, and senior military officers can spot that in an instant.) At the same time, as the positive interaction experienced in Iraq and Afghanistan fades, some American military commanders who want to have more say over their foreign policy adviser shops have been opting for direct hires from among retired military officers—known quantities—rather than State-DoD details.

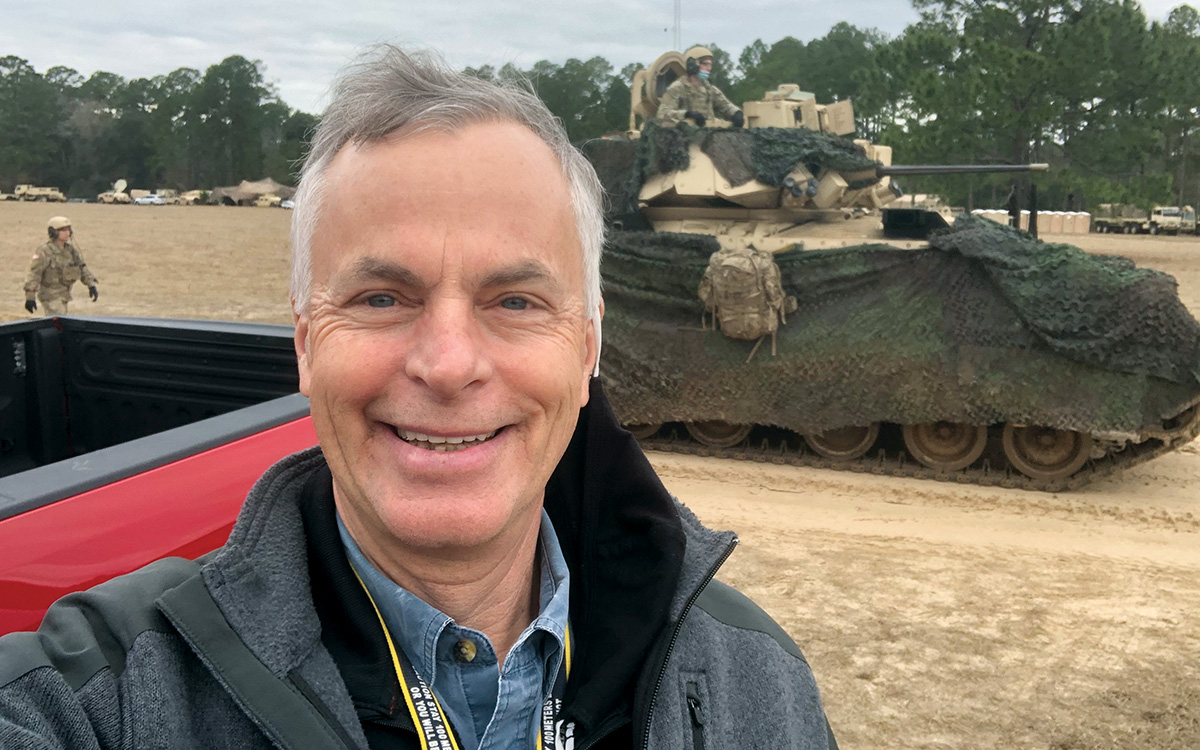

Larry Butler supporting an exercise with the 3rd Infantry Division at Fort Stewart in 2021.

Courtesy of Larry Butler

The Bottom Line

Here are some of the nitty-gritty factors that made my postretirement experiences possible and could help with yours.

Networking. Much like my Foreign Service career, nearly every contract I have found me. Some were thanks to a tip from a fellow role player, others from former State and Department of Defense colleagues. One’s reputation combined with effective networking is a force multiplier, another of my “laws”—it isn’t who or what you know, it’s who knows you. I get several recruiting help requests monthly and have recommended about a dozen retired, or retiring, colleagues for jobs. There are dozens of companies, larger and smaller, that hire retired FSOs ranging from midlevel officers to former chiefs of mission. Valiant, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon (and their subcontractors) are the major players, but there are also many small firms. LinkedIn is a good way to find them, or help them find you, and to do proactive networking long before you retire. A case in point: my turning down another chief-of-mission assignment in favor of going to the U.S. European Command in Germany for my last Foreign Service gig. Connections made there led to multiple post-employment job opportunities.

Security clearance. All of the things I list require at least a current secret clearance, and the company that hires you will hold that clearance under the DoD system. The longer you are away from State and not in the DoD system, the harder to regain a clearance.

Experience and “life” expectancy. I spent much of my career in conflict/crisis locations working closely with the U.S. military; my last three assignments were with the military. The military customer wants the real deal, someone who has authentic overseas experience and is fluent or can become fluent in military jargon and acronyms. But military exercises can be contrived, which can be challenging for an FSO to accept. This has led to some being invited to leave and never come back. One’s relevance to the military has a shelf life; you are most valuable the day you retire, but it is possible to keep up by maintaining good contacts with the current Foreign Service—I read AFSA’s daily Media Digest religiously. And I subscribe to the department’s emailed announcements about what senior officials are doing.

You are a contractor, and personality matters.

Employment status. I established a sole-proprietorship LLC (easy to do in Virginia) as the preferred vehicle to sell my services to most defense contractors, which makes me a “1099-MISC” self-employed person for income tax purposes. However, several of my employers have me on their rolls in a “part-time, on call” status, which means they deduct for taxes and social security. Sometimes this means benefits not available in the LLC relationship, though IRS has very generous options to contribute to a “Simplified Employee Pension Plan” (SEP) IRA if one is so inclined.

Culture shock. Members of the military have a fixed idea about who we FSOs are: liberal tree-huggers, savers of whales and promoters of socialist values. If you want to work for the military, you have to expect a conservative (and very well-educated) group of people. They are OK with you bringing a different set of values and perspectives (I get humorously stereotyped early and often), but you should ask yourself, are you capable of returning the favor? I get too many sad anecdotes from my “customers” of how they are treated by FSOs overseas.

Employment security is an oxymoron. Contracts come and go. The company I started with lost all the contracts it had with the Army, but the competitors that prevailed on two picked up the interagency team. Several times I got hired for a one-off event. Other times the requirement for role players changed, and positions were eliminated. And there are plenty of people seeking these opportunities. The first time you turn down an opportunity, you might never hear from that company again.

Final words: you are a contractor, and personality matters. Team players who get along well with a diverse group of people succeed. Those who don’t, don’t get invited back.

Read More...

- “Working With the U.S. Military: 10 Things the Foreign Service Needs to Know,” by Ted Strickler, FSJ, October 2015

- “Creeping Foreign Policy Militarization or Creeping State Department Irrelevance?” by Larry Butler, FSJ, June 2017

- “Working with the U.S. Military: Let’s Take Full Advantage of Opportunities,” by Wanda Nesbitt, FSJ, June 2017