Hispanic Representation at USAID: Why So Low for So Long?

Speaking Out

BY JOSÉ GARZÓN

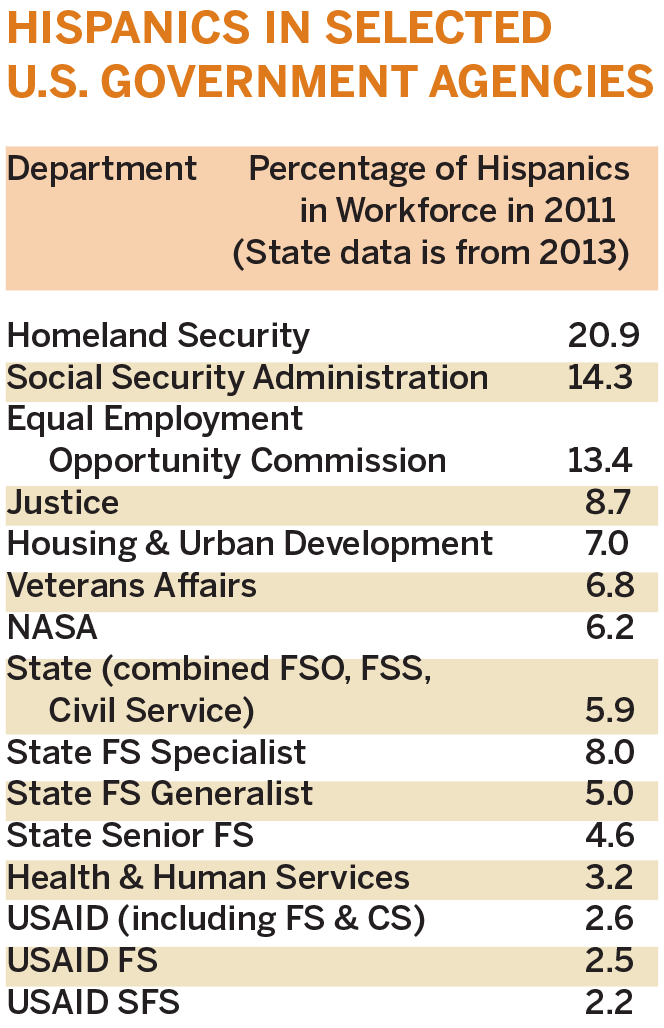

Sources: OPM: Eleventh Annual Report to the President on Hispanic Employment in the Federal Government, July 2012; USAID/OCRD Diversity Profiles, June 2012; Department of State, Diversity Statistics as of 9/30/13.

Periodically, I am asked to speak to Hispanic and minority students aspiring to enter the Foreign Service or the U.S. Agency for International Development. I can hardly resist the chance to tell my own life story and describe the places where USAID has sent me. The Foreign Service is a great career, I tell them, and I encourage them to consider taking the plunge.

One reason I’m tapped to give these speeches is that I’m a 25-year veteran of the Foreign Service, and also a member of an endangered species: mid-level Hispanic FSOs. My agency is sincerely trying to recruit a more diverse workforce, but has consistently failed in terms of Hispanic representation since the late 1970s, when data on ethnicity began to be collected.

Recently I asked several members of USAID’s senior leadership and Office of Civil Rights and Diversity for their thoughts on why the agency’s record is so poor. Here are some of the responses I got:

- This is a governmentwide problem, and USAID does as well as or better than other U.S. agencies.

- Things are getting better.

- You need a graduate degree to obtain most positions in USAID, and the pool of Hispanics with graduate degrees is limited.

A social scientist by training, I decided to peek behind the curtain and examine the evidence. It turns out that all these responses are wrong.

Re-Examining the Conventional Wisdom

First, let’s take the assertion that USAID is “doing no worse than everyone else.” Oh yes, it is. As the table to the left, based on the most recent data from the Office of Personnel Management and USAID, shows, USAID is at the bottom among federal agencies in Hispanic representation. The percent of Hispanics at the State Department is about twice as high as at USAID, and in the case of State Foreign Service specialists (at 8 percent), almost three times as high.

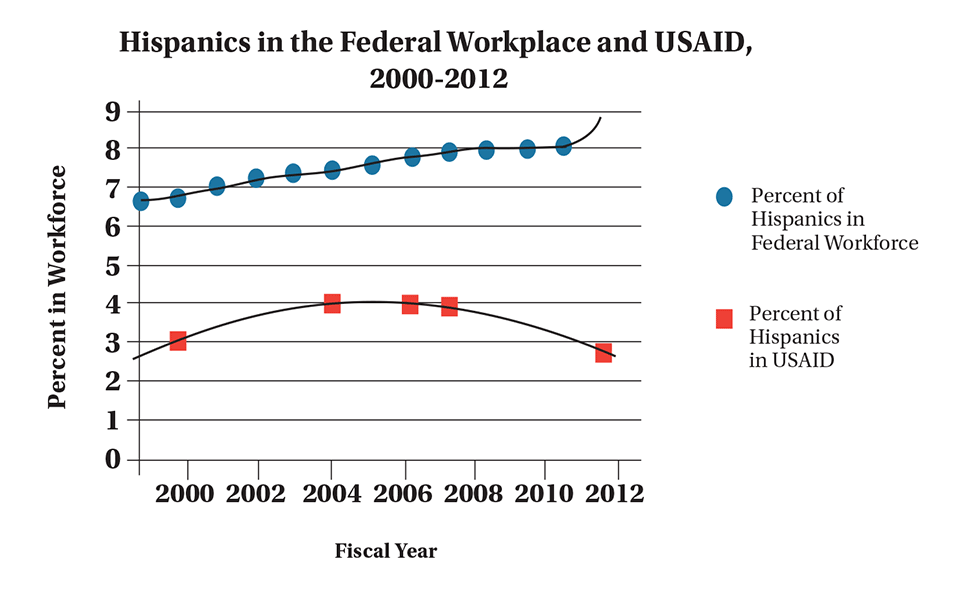

Well, at least it’s “getting better,” consistent with demographic trends, right? No, it’s actually getting worse.

USAID is at the bottom among federal agencies in Hispanic representation.

True, Hispanic representation in the U.S. government is improving, rising from 6.5 percent in 2000 to 8.1 percent in 2011, according to OPM’s Eleventh Annual Report. But at USAID, the trend is slipping backward. Twenty years ago official USAID/EEO staffing reports showed a Hispanic workforce of 3.1 percent out of 3,346 employees, according to the 1992 Report to the Transition Team by the Hispanic Council. In 2005, Hispanics comprised 4.1 percent of the USAID work force.

But by 2008 the percentage had begun slipping, and in 2012 it stood at just 2.6 percent. This is despite a significant surge in overall hiring at USAID, a surge that has stopped and will likely usher in years of limited hiring—meaning that a golden opportunity to improve these dismal numbers may have been lost for some time.

Learning from Our Past

Here’s where the story gets really interesting. Back in the 1960s, USAID’s top foreign policy priority (other than the Vietnam War) was combating communism in Latin America. In reaction to a perceived communist threat to Latin America, USAID quickly ramped up Hispanic hiring, with no pretense of promoting affirmative action or diversity. Old-timers I met when I first began working with USAID in the 1980s told me that recruiters went to Puerto Rico and scooped up graduates, some of whom stayed on with the agency until about the 1990s.

Perusing the 1970 staffing pattern, which one can find in the recesses of the USAID Library, one finds Hispanic surnames galore: Cabrera, Hernandez, Hinojosa, Romero, Vasquez, etc. The Office of Public Safety lists 11 such surnames out of 106, or about 10 percent of the staff. The 1970 USAID mission roster in Bolivia shows an even higher number—six out of 45, including the deputy director, or 13.3 percent—while the Dominican Republic staffing pattern features five Hispanic names out of 46, 10.9 percent.

Sources: OPM Eleventh Annual Report, July 2012; USAID/M/HR, Annual Federal Equal Opportunity Recruitment Program, FY 2001; ICF Consulting, Incorporating Affirmative Employment Goals into USAID’s Work-force Strategies, Oct. 15, 2005; Office of Equal Opportunity Programs, Diversity Profile FY 2007-FY 2008, Nov. 14, 2008; OCRD Diversity Profiles, June 2012.

Admittedly, this is an imperfect measure. But it does indicate that when hiring large numbers of Hispanics was linked to a national priority, the agency made it happen.

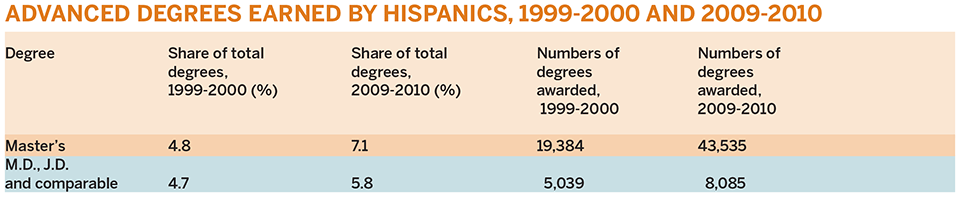

That brings us to the third explanation for the current shortfall in Hispanic hiring: “Back in the 1960s and 1970s, USAID would hire people straight out of college. Now you need a graduate degree. And it’s hard to find Hispanics with that qualification.”

Un momento. Yes, graduate degrees are required for most positions (although that practice should be re-examined). But what the assertion ignores is that the number of Hispanics with master’s degrees has more than doubled over the past decade, and the numbers earning law and doctoral degrees have shot up by 60 percent over the same period.

Is better recruitment the answer? USAID’s Human Resources division and Office of Civil Rights and Diversity have launched some sincere efforts in this regard, and more resources should be devoted to recruitment. But I suspect these efforts may be falling short because of the disconnect between recruitment and the technical panels, which actually select candidates and are less focused on diversity goals.

I should know. I’ve served on these panels.

When hiring large numbers of Hispanics was linked to a national priority, as in the 1960s, USAID made it happen.

And Then There Were Four

Recruitment is to the lower ranks of the agency, with the hope that a greater pool of junior officers will eventually push its way up the ranks. Little thought has gone into the pull factor: the process by which senior officials and officers recruit, mentor and promote junior officers, giving them good opportunities and encouraging them to stay at USAID.

During the 1990s, USAID began to promote more women into the Senior Foreign Service, which in turn changed the agency’s culture and gradually increased the numbers of women in the Foreign Service. But the number of Hispanics in the Senior Foreign Service between 2009 and 2012 can literally be counted on one hand: four out of 176. OCRD identifies just two Hispanics out of 33 in the Senior Executive Service. And that is actually an improvement over 2009 and 2010.

This illustrates a more serious disconnect, between stated diversity goals and the goals of the people who make the actual selections—those at the top of the agency. I really believe USAID’s leadership is conceptually committed to diversity. But it has many other priorities, which crowd out diversity as a goal.

Source: Department of Education, NCES: Graduate Enrollment and Degrees, 2000-2010 (2011).

During the Cold War, fighting communism in Latin America was the agency’s priority, and that led to a major upsurge in Hispanic recruitment. Today, priorities such as USAID Forward, Feed the Future and Resilience draw executive attention elsewhere. In addition, despite genuine attempts to create more transparency, and with due respect to those who advise on career management, promotion into a Senior Management Group position depends heavily on sponsorship from above. That is clear from the varied levels of experience in new SMG picks.

The result is a vicious circle: limited promotion means limited mid-level promotions and limited hiring. And that, I believe, is the reason why USAID is sliding backward when it comes to Hispanic representation.

A Better Way Forward

José Garzón speaking at the inauguration of a school project in Kosovo in 2011.

A great deal of energy has gone into better recruitment, and those efforts should continue and be expanded. For example, USAID might create and fund a recruitment unit that operates the way college sport teams do: direct contact. It could tap into the networks of contractors, grantees and fellows to encourage them to apply for open positions, while monitoring the work of technical panels to ensure strong candidates receive due consideration.

But that needs to be accompanied by a broader effort—not only on behalf of Hispanics, but to benefit everyone at USAID—to cultivate a diverse Senior Management Group cadre. Of course, managers will continue to recruit the people they want, and they cannot be blamed for that. But someone has to be an advocate for those groups who are consistently left out, and it has to be someone with clout who can overrule a selection. If a qualified Hispanic (or other minority) has applied for an SMG position, there must be a compelling reason not to select that candidate. “I like this person more” is just not acceptable.

Secondly, while I am pleased that mission directors and others are being held accountable for diversity, we need to reward those who demonstrate that they can mentor and nurture other staff, especially those from underrepresented groups. “Managing down” needs to become part of “managing up,” not just a good deed that has its own rewards.

'Managing down' needs to become part of 'managing up,' not just a good deed.

There are plenty of rewards for writing policies and strategies or getting involved with “what’s hot” at the moment. That’s fine. But if I were the USAID Administrator, I would ask my senior managers: “Tell me what you have done to help someone on your staff overcome obstacles to promotion.” If they can’t answer that question in five seconds, I would send them back to come up with a diversity strategy, on one page, in 24 hours. I would also make sure they pose the same question to their own subordinates. And I’d pose the same question to the technical panels that make the actual personnel selections.

As I like to tell potential recruits, in my career I have seen dramatic changes in USAID, as well as a return to old ways of doing business. Then there are those things which never seem to change. I hope that one of these recruits, 25 years from now, can say that USAID is an agency that is fully representative of the American public. But it shouldn’t take that long to happen.