1950s—The McCarthy Witch Hunt: Who “Lost” China?

In February 1950, months after Mao Zedong’s establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Senator Joseph McCarthy, R-Wis., gave his infamous speech accusing the State Department of harboring communist agents and sympathizers. FSO John S. Service, one of the State Department’s top experts on China, one of the so-called China Hands, was among those caught up in the spurious charges. With deep knowledge, and experience on the ground in China, Service had been reporting since the early 1940s that Mao’s forces should not be underestimated, and that the United States could not assume that the Chinese Nationalists would succeed against them. The U.S. would need to deal with the communists.

For this, Service was fired in December 1951. Six years later, the Supreme Court ordered his reinstatement, but the damage to the Foreign Service, and U.S. Asia policy, was done. As Senator J. William Fulbright, D-Ark., would later say, during a hearing in 1971: For doing their job, reporting about conditions in China, “[the China Hands] were so persecuted because [they] were honest. This is a strange thing to occur in what is called a civilized country.”

Here are excerpts from John Service’s account of the McCarthy witch hunt as he experienced it.

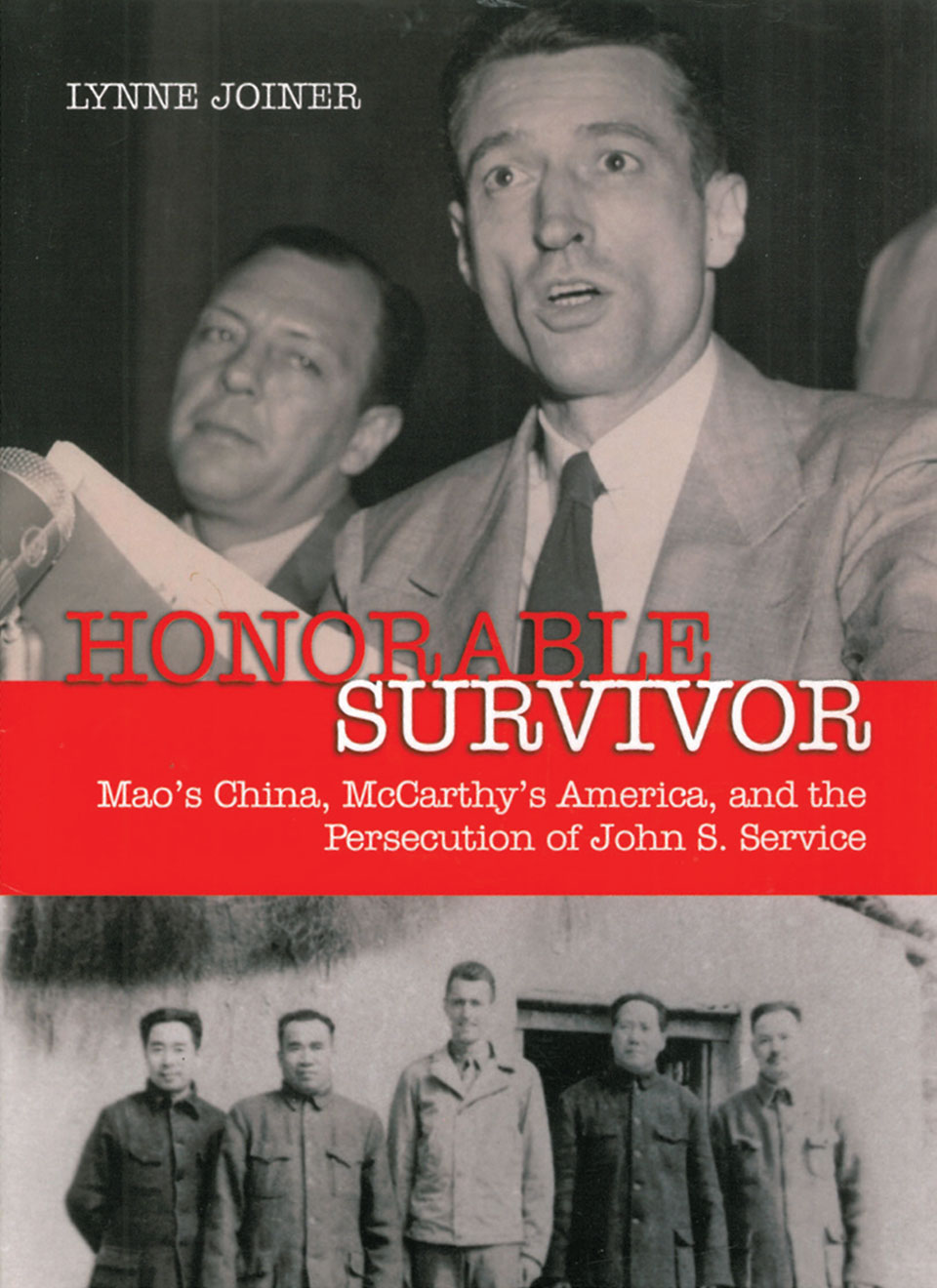

John Service answers a question at his loyalty hearing in 1950 on the cover of Lynne Joiner’s book (Naval Institute Press, 2009) about his experience as a Foreign Service China Hand and a target of the McCarthy witch hunt. In the lower image, Service (center) meets in 1944 with, from left, Zhou Enlai, Chu Teh, Mao Zedong and Ye Jianying in Yenan.

Chris Gamboa-Onrubia, Fineline Graphics LLC

We were going by freighter from Seattle to Yokohama on our way to India [and his new assignment]. One night at supper [the radio operator] said, “Say, is your name John Stewart Service?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “There’s been a lot of stuff about you on the radio news, talking a lot about you in Washington.” This was the first intimation we had.

A day or two later I got a telegram from the department saying I should return because of charges by Senator McCarthy. The family could either remain in Japan or go on to India.

We decided they should go on to India. We expected that there would be a hearing. We knew from the radio broadcast that a Senate committee had been set up.

[I was] certainly annoyed, uncertain of course, about what was going on, but not particularly concerned. After all, I’d been through the Amerasia case [Service was arrested by the FBI on suspicion of passing classified government documents to a Far Eastern affairs journal in 1945] and gotten a unanimous clean bill.

The department went all out. The department’s policy was obviously to meet McCarthy head-on. A big welcome was planned for me.

[Senator Joseph] Tydings’ committee hearings had been going on for three months and had produced a great deal of furor, but no clear refutation in the mind of the public of [McCarthy’s] wild charges. We had three days of hearings. The third day they insisted on being closed because they’d had this so-called secret recording of a conversation between [Amerasia editor Philip] Jaffe and myself. It wasn’t a recording at all. It was a transcription, an alleged transcription, of some sort of a wiretap or a listening device put in a room in Jaffe’s hotel. It was incomplete and very garbled.

We got, finally, a statement out of the Department of Justice; and they said that it was excerpts, portions, of a transcript and that the original had been destroyed. It’s got me—as we say in the testimony—saying things that I couldn’t possibly have said.

It’s been argued that we should have made more of an issue—perhaps by refusing to be interrogated on the basis of such clearly illegal evidence. We took the point of view that when the loyalty of a public officer is involved, we were not going to make an issue of whether or not the evidence was obtained in a proper way. In a court of law, of course, it would not have been admissible.

They had a terrific hassle in the Senate as to whether or not they would accept [the final report], and split on strict party lines. Tydings went after McCarthy hammer and tongs. The conclusion of the report was very favorable to me.

In the November 1950 elections, Tydings was defeated and a nonentity was put in. This really added greatly to McCarthy’s political threat. After the election [the State Department] became very much more cautious.

The State Department [Loyalty Security] Board [which had conducted its own investigation] had told me in June, when they finished the case, that they were satisfied. But new information kept being produced. New accusations would come in. Every time this happened, the case had to be reopened. It was very difficult to ever bring anything to a close.

Originally, there had to be a reasonable basis to consider you disloyal. That was changed to reasonable doubts as to loyalty.

–John S. Service

Then the standards were changed. Originally, there had to be a reasonable basis to consider you disloyal. That was changed to reasonable doubts as to loyalty. All cases had to be reconsidered under the new rules.

[The department] decided that I would have to be kept in Washington. [It] publicly announced in December 1950 that I had been cleared. But this was only provisional.

[As Service explained in his interview, there were two levels of boards under the Loyalty Security program set up by President Truman in 1947. Each department had its own board, called the Loyalty Security Board. Then up above, nominally under the Civil Service Commission, was the Loyalty Review Board. All cases were decided by the department boards and then went up to the LRB for this review process, usually called “post audit.”]

On Oct. 11, 1951, we got a letter rather surprisingly from the Loyalty Review Board saying that they were going to hold their own hearings on Nov. 8. [On July 31 the State Department had reaffirmed its findings that Service was neither disloyal nor a security risk; then on Sept. 4 it referred the case to the Loyalty Review Board for “post-audit.”]

A staff member of the Loyalty Review Board asked some silly questions. He was a real know-nothing type. The only one of his questions I recall was to the effect that I had referred to “C-C” many times in reports, to the “C-C Clique,” and did this mean Chinese Communists? Well, of course, the C-C Clique is well known to anybody involved in Chinese affairs. It meant the Chen brothers, Chen Kuo-fu and Chen Li-fu—the right-wing clique of the Kuomintang.

This was the expertise of the staff of the Loyalty Review Board.

We said later on that we would like to submit a memorandum, and they said we could. We got a delay until we could get the transcript. As soon as I read the transcript it was clear to me that they had in their minds quite different charges. The original charge [at the Department Loyalty Security Board] was that I was a communist or associated with communists in such a way as to betray the security interests of the United States. The charge that they had in mind was about “willful disclosure of confidential information.”

What to do about the mixup in the charges? [The board] said, “Well, we can have hearings all over again if you want.” But they didn’t think it would make any difference.

About this time, my friend [FSO and China expert Raymond P.] Ludden had received an interrogatory. Many people were beginning to receive interrogatories. Ludden was very concerned about how to handle it. There was some question of the procedural details. I said to him, “Well, let’s go down to the Loyalty Security Board’s office.”

So we walked in, and [the fellow at the desk]’s face froze. “How did you know so soon?” he said.

“Know what?” I said.

“The Loyalty Review Board has ruled against you.” They told us about it. The secretary had red eyes. She obviously was upset. Everyone was upset. There wasn’t much to do.

I called [my attorney] Ed, and he immediately asked for a delay.

Ed felt very strongly that we had a case, that the Loyalty Review Board did not have this authority to overrule cases that had been decided in favor of the employee. They could be an appeal board, but since the State Department had not appealed, they couldn’t arbitrarily assume control of a case, as they were doing, and then decide against the employee.

[But State] refused to consider any delay or hold it up: “Too late. Press has already got these releases.” The State Department had a lengthy press release, the full text of the Loyalty Review Board’s decision, and the full text of their own board’s decision, saying that I would be fired as of the close of business the next day.

We don’t know for sure, but as far as we could find out, the State Department immediately got in touch with the White House and said, “What do we do?”

The White House said, “You’ve got to fire him. Too much heat. The president has appointed the Loyalty Review Board, he can’t overrule them, and you’ve just got to go ahead and fire him.”

The whole attitude of the State Department people under Dean Acheson was to save the Secretary as much as possible because he’d been burned so badly on the [Alger] Hiss case, you see. After Hiss was convicted, he made a statement, “I will not turn my back.” The repercussions and backlash on this had been venomous and terrible.

One of McCarthy’s favorite ways of referring to me, for instance, in public speeches was, “John Service, whom Acheson will not turn his back on.” You know, this sort of thing. I’m not sure whether Acheson was involved. I suppose he must have okayed it.

A group of Foreign Service officers tried to talk to him about the case. I think he intimated to them that he just couldn’t do anything about it, his hands were tied. So I think it all points to the fact that the real decision was made in the White House.

I don’t think I was used as the [State] Department scapegoat. There’s just no basis for that. The department, as I say, was pretty much on my side. The State Department at the top level tried to cut its losses at the last minute. They weren’t going to make any fight about it. But up to that point they had stuck by me through a lot of thick and thin.

I was a scapegoat in a sense, a whipping boy… [but] that isn’t the right word. I turned out to be an easy, vulnerable target for McCarthy and for the China Lobby.