Straight Talk on Diplomatic Capacity

Lessons learned from the Tillerson tenure can help the new Secretary of State enhance the State Department’s core diplomatic and national security mission.

BY ALEX KARAGIANNIS

President Donald Trump’s firing of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and intention to nominate CIA Director Mike Pompeo as his replacement could have profound implications for the reforms that Secretary Tillerson initiated at the State Department. What will not change is the fact that State employees, including career members of the U.S. Foreign Service, are eager for serious, sober and substantial reforms that will enhance the effectiveness of the State Department’s capacity to carry out its core diplomatic and national security mission.

Tillerson’s “redesign” initiatives were ill-equipped to do that; they front-loaded staff and budget cuts rather than determining strategic priorities, strengthening capabilities and building advantages. The now-common sport of analyzing the damage done to the State Department during the past 16 months understates the problem. It’s worse when examining hard data in historical context.

The new Secretary can take simple but consequential steps that boost State’s ability to drive and execute policy and deliver results for the United States. Here are my suggestions:

• Draw on the talents of State’s professionals. They are as capable, determined and mission-driven as their colleagues at the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense and other national security agencies.

• Fill under secretary, assistant secretary and ambassador positions on the basis of qualifications. Judgment, initiative, curiosity and experience count; amateurism has consequences.

• Establish strategic priorities: sustain the budget, suspend the hiring freeze and hire to at least attrition until results are in.

• Create investment funds for human capital training and development and a new information technology architecture; these are multiyear outlays that need dedicated long-term resources.

• Staff and empower a change management team that will oversee and implement the back-office reforms now underway; devise solutions to structural and systemic rigidities, anomalies and misalignments; and communicate continuously with employees and stakeholders.

Viewing the Deconstruction

In 1969 Dean Acheson published his seminal, Pulitzer prize-winning book, Present at the Creation. It covered the extraordinary time in the late 1940s when clear-eyed, hard-headed, tough-minded Americans reshaped the world, creating new organizations and institutions to establish a stable system of international relations. Seared by the events of the 1930s and 1940s—world economic stagnation/depression, ethno-nationalist jingoism, fascism, authoritarianism, totalitarianism, civil wars, foreign aggressions and a global conflagration in which America fought a two-front war—they were determined to found a new economic, political and security architecture.

Through it, for the next 70 years the United States led the world in extending liberty, democracy, prosperity and justice; drew in allies and partners; and created conditions for peace and human dignity unparalleled in human history.

Today it appears to many that the Trump administration is equally determined to deconstruct that system—as it looks inward and focuses on the tactical and transactional, oblivious to opportunity for the transformational. Central to this effort, Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney started the budget process by proposing to slash the State Department’s Fiscal Year 2018 budget by 31 percent. Then, in February 2018, he tabled State’s FY2019 budget with a new 23 percent cut from the FY2017 enacted levels.

Although Congress signaled—and acted on—its opposition to the administration’s proposed budget for State, that posture alone will not displace a national security policy that sidelines diplomacy. America today faces an international environment that is volatile, dangerous and complex. Its adversaries are aggressive and capable; nonstate actors are numerous and lethal; regional and transregional threats are growing more sinister; and ideological movements are increasingly pernicious and inimical to democratic interests. A strong, capable State Department would bolster other instruments of national power and offer a broader spectrum in which to operate.

Trump’s plan to boost defense spending while slashing State’s diplomatic capacity (resources and people through a 23 percent cut in the overall budget, with a 26 percent reduction in operational funds) faces a problem. However much it is necessary, defense spending will take years to increase readiness (e.g., by producing more planes, ships and missiles). Moreover, it is ill-suited for pressing current challenges. Russian cyber-meddling, refugee flows, humanitarian crises, disease outbreaks, lagging exports and investments, and trade disputes do not easily lend themselves to military solutions. Rather, they require active, preventative and long-term, front-line diplomatic engagement.

Targeting Staff

When Rex Tillerson arrived at State, employees welcomed him, hopeful his private-sector experience would help strengthen the department. These hopes were off the mark. Tillerson had a rocky tenure; he did not establish a close working relationship with Trump, or with his 535-member board of directors (aka Congress), or with domestic constituencies and stakeholders. Unable to get his personnel choices past the White House, he had a very spare bench of confirmed under secretaries and assistant secretaries. And he appeared to have little trust in or time for the career professionals, disposing of many gracelessly. His chief of staff and deputy chief of staff were national security novices, more adept at micromanaging than leadership. Morale plunged, and the department was seemingly adrift, as amply chronicled in many academic, think-tank and media analyses.

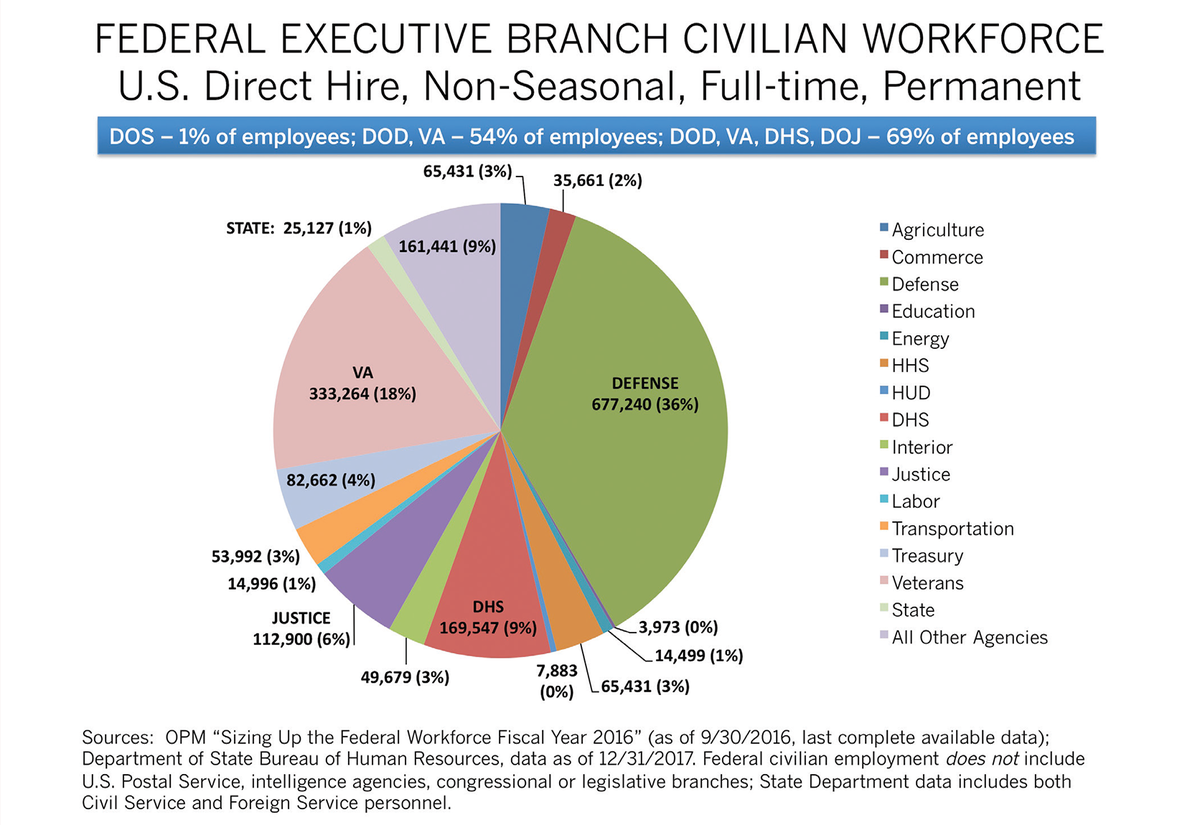

Secretary Tillerson initially resisted but then acquiesced in the 31 percent cut submitted by OMB for the FY18 budget. Though that budget went nowhere on the Hill, he demanded commensurate workforce reductions, only grudgingly scaling them back even though State’s total staff numbers would barely amount to a rounding error at the federal level. State accounts for just 1 percent of executive branch civilian employees and only 1 percent of the federal budget (see chart below). The federal government spends nearly as much on Lockheed Martin as on State, according to a Feb. 16 Washington Post analysis.

Tillerson also extended the president’s temporary hiring restrictions indefinitely and applied them even to eligible family members, disrupting operations at overseas posts and undermining productivity and morale. He insisted his staff review all exemptions, prompting a blizzard of paperwork that elevated routine tasks to Secretarial level.

Further, he pushed a “Redesign” (later rebranded “The Impact Initiative,” or TII) intended to reshape the State Department, hiring two outside consultancies to facilitate an ostensibly employee-run process. The consultancies labored under shifting direction and leadership, with “work streams” that were more siloed and stove-piped than integrated teams.

Rather than accelerate reforms, the process sidelined and stalled initiatives by the bureaus of Human Resources and Information Resource Management and other bureaus that were already underway. From a change management perspective, Tillerson’s team heeded none of the experts in establishing a clear vision, ideal end state, timelines, champions or a coherent communications strategy. The changes prioritized back-office, legacy and operational matters (all of which must, of course, be addressed), but did so without first establishing strategic priorities and strengthening core functions and responsibilities.

Déjà Vu All Over Again

By focusing first on workforce numbers rather than strategic purpose, the initial actions began gutting the State Department of professionals with the experience, knowledge and judgment to articulate and execute policy and get results. Ignoring Government Accountability Office reports of the 1990s and mid-2000s that had sounded the alarm concerning the deleterious effects of staffing gaps and deficits at State, Tillerson and his advisers insisted on drastic cuts.

In doing so, they flew in the face of history. Following the dissolution of the USSR and Yugoslavia, State had staffed 19 new embassies with existing personnel and flat budgets. That was followed by the Clinton-Gore “Reinvention of Government” exercise that saw steep budget and staffing cuts, and then the disbanding of the Arms Control and Disamament Agency and the merger into State of the U.S. Information Agency, engineered by Senator Jesse Helms. That exercise brought 2,100 employees into State without funding for their integration, but did not constitute a net gain in Foreign Service personnel.

After 9/11, the department moved to expeditionary and transformative diplomacy, staffing two mega-missions in Afghanistan and Iraq through volunteers, while drawing down elsewhere to meet those needs. Secretaries of State Colin Powell and Hillary Clinton took action to address GAO concerns, and with the backing of Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama and Congress’ approved budgets, State hired new personnel to close staffing deficits. But State’s post-9/11 growth was highly uneven.

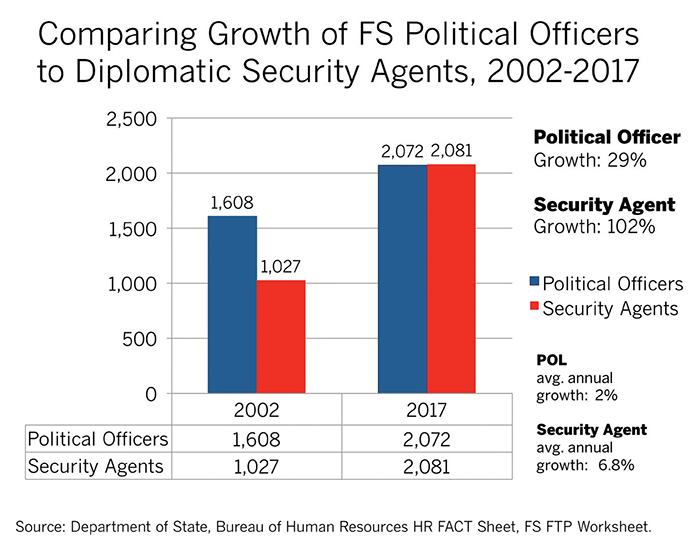

To cite just a few prominent examples, since 1995 Diplomatic Security Bureau personnel increased by nearly 200 percent; consular personnel (processing visas for foreigners and passports for U.S. citizens) grew by more than 160 percent; and other specializations grew by more than 100 percent. In contrast, core diplomatic staff grew by just 42 percent (2 percent on an annual basis), even as their responsibilities and overseas deployments to dangerous postings increased.

At any given time, two-thirds of the Foreign Service is overseas, serving in more than 270 embassies and consulates. In dozens of posts, other agencies outnumber State Department personnel.

Running into Facts

The focus on budget cuts and workforce reductions also ran into stubborn facts. The proposed 31 percent budget cut for FY18 could not produce commensurate workforce savings. Five bureaus comprising 5 percent of the workforce accounted for 80 percent of the funds to be reduced (assistance, contributions to international agencies, exchanges). Even eliminating those bureaus entirely would yield only a 5 percent staff reduction.

Tillerson eventually settled for an 8 percent total workforce reduction of U.S. direct-hire personnel by the end of September 2018. That number was arrived at only after more draconian reductions (on the order of 15 percent or more) were shelved because they would have required a costly and protracted reduction-in-force exercise. The 8 percent downsizing was predicated on attrition, incentivized attrition (buyouts) and reduced intake. For FY17, intake was capped at 77 percent of attrition for the Foreign Service (the actual number was lower); for FY18, the cap was 40 percent of attrition. For the Civil Service, it was worse: zero hiring in FY17; and 25 percent of attrition in FY18.

Because the Foreign Service brings in new employees in cohorts, reduced hiring has a generational impact, exacerbating the types of deficits that GAO had previously identified. For the Civil Service, in particular, it means a collapse of expertise in key bureaus. No process improvements, which are geared to back-office functions, will make up for the resulting policy and operational shortfalls.

When defending staffing numbers Tillerson’s staff often pointed to the fact that the State Department employs 75,000 worldwide, suggesting its workforce is huge. But 50,000 of those employees are local nationals, the majority of whom perform security work (approximately 37,000), initial visa screening and other essential internal operational activities that support several dozen other federal agencies at overseas missions. Those local employees were never part of the reduction exercise—that exercise was targeted at the 24,775 U.S. direct-hire Foreign and Civil Service personnel on the rolls as of Jan. 31, 2017.

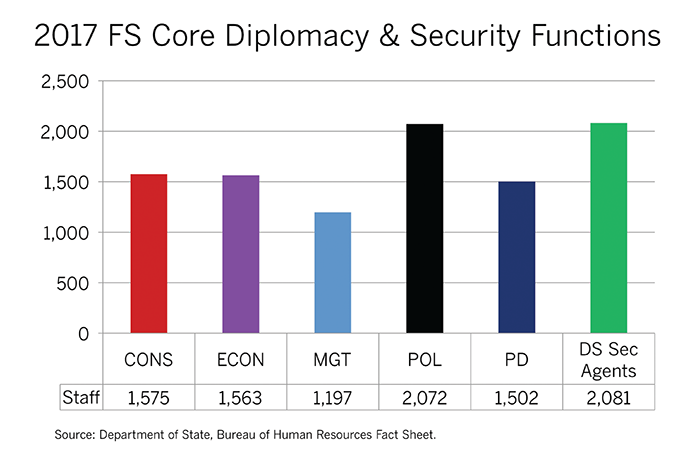

To hit the mark of 1,982 fewer employees and account for minimal (well below attrition) hiring, approximately 2,300 employees would need to leave the rolls—a huge and disruptive churn. Even worse, the Tillerson plan failed to address structural and systemic anomalies. For example, approximately 67 percent of the Foreign Service serves overseas at any given time. But more than 50 percent of DS agents serve stateside, even as the threats and risks to U.S. personnel and facilities are abroad. DS agents have now edged out political officers as the largest cohort in State. They exceed by 500 each the economic, public diplomacy and consular officer cadres, and number close to 900 more than management officers. This can hardly be characterized as an optimal mix.

Moreover, five bureaus (led by Consular Affairs and Diplomatic Security) account for 70 percent of Civil Service positions. Their hiring, which is given priority under the staffing exercise as those bureaus have deficits, automatically means that the needs of other bureaus in the State Department may be nearly shut out—whether in arms control, non-proliferation, sanctions enforcement, trade promotion, civil aviation, energy, human rights or a host of other critical areas.

Tillerson and his senior team downplayed the loss of senior leaders and career ambassadors. It is normal to see retirements at those ranks. What is unusual is that so many were forced out at one time—a precipitous decline when contrasted to the many vacancies at the assistant secretary level and many posts lacking ambassadors.

Budget Reality

Though Tillerson and his staff claimed that State’s budget was unsustainable, they offered no empirical evidence in support and made no business case why drastic retrenchment in budget and personnel was necessary. The department has yet to put budget figures into context, either historically or in comparison to national security spending overall. In fact, State’s budget has declined since 2008.

The operational budget for core diplomacy functions (the Diplomatic and Consular Programs account) has been on a downward slope since 2010, even as requirements grew. Budget growth came in the form of separate outlays for security, embassy construction and other administrative functions. Funding for diplomacy shrank, both in nominal and inflation-adjusted terms, severely straining capacity to advance America’s national security, economic and trade interests.

Juxtaposition of the budget and staffing numbers clearly shows a slow, gradual retrenchment, now dramatically accelerated. No efficiency improvements will substitute for or translate into diplomatic acumen, capabilities or clout in the policy arena at home or abroad.

In looking closely at the president’s FY19 budget request, several warning signs pop out, as the Brookings Institution noted in a Feb. 13 report by Thomas M. Hill, “What Trump’s Budget Means for the State Department—Snap Judgments.” First, OMB manipulated various funding accounts to disguise de facto cuts.

Second, it both sliced the Overseas Contingency Operations account and shifted it into State’s base operational account. That could be a sensible solution because it requires State (and Congress) to deal with normal operations, not indefinite special circumstances. But it does not change anything on the ground. State still needs to spend huge funds in Afghanistan, Iraq and other conflict areas for ongoing operations; none of those funds are easily reprogrammed to address needed structural reforms or develop a future workforce for new challenges.

Third, it cleverly (some say deviously) shifts monies between programmatic and operational accounts, making both targets for future cost-cutting exercises when the programs are found “ineffective” or “duplicative” and the workforce must be reshaped (downsized) for the sake of efficiency.

And fourth, while everyone recognizes that State requires a massive IT upgrade and modernization—with a whole new architecture and state-of-the-art, secure data management, data visualization and messaging systems—there are no new dedicated funds for that. Rather, it appears that monies are reprogrammed, tapped from the Bureau of Consular Affairs’ fee-generated revenues for departmentwide IT needs. In short, the FY19 budget proposal is a shell game of robbing Peter to pay Paul.

Moreover, State’s payroll costs are less than 10 percent of its total budget, a budget that also supports physical and virtual presence to expand U.S. influence even where programs are declining. State provides a security and administrative platform overseas for more than 30 other U.S. government agencies, many of which have increased their overseas footprint and need for services that State provides. Cutting State’s budget would have wide repercussions.

Three conclusions about the administration's budget proposals were painfully obvious: The Trump administration looked to ignore Congress, which favors healthier funding for State; if enacted, the budget would make State more a support service for other agencies than a strong diplomatic agent; and it would generate a diplomatic void that Russia, China and other adversaries will gladly exploit.

In March Congress passed and President Trump signed an omnibus spending bill. It calls, inter alia, for the State Department’s Inspector General to review the “Redesign” to ensure it used proper processes and included employee input. State is also required to report to Congress on actions it took in response to Trump’s reorganization directive to all federal cabinet agencies and subsequent guidance from the Office of Management and Budget. Congress further noted that it expects State to maintain FS and CS staff levels on board as of Dec. 31, 2017.

Fewer employees and lower budgets rarely produce great results in a diplomatic arena where intractable problems bedevil policymakers and initiative, judgment and expertise are at a premium.

Under this budget, State avoids the most deleterious consequences of painful cuts, but is far from being put on an upward trajectory in building diplomatic capacity for the future. It is still necessary to address structural rigidities, anomalies and misalignments. And it is essential to redress systemic underinvestment in people (the entire human capital development life cycle) and information technology.

Moreover, by itself this budget does not address State’s and diplomacy’s marginalization as an instrument of U.S. leadership.

An Uncertain Future

All of this has had a predictable, debilitating effect on the State Department and its employees, who have long wanted constructive change. Indeed, the professionals at State had already launched numerous reform initiatives to strengthen the department; many were stalled as the focus shifted to the “Redesign/TII.” To cite only a few projects already underway: a new IT architecture (including email and messaging systems; data hygiene, migration, integrity and visualization); new performance management systems for both the Foreign and Civil Service; new assignment and deployment patterns for the Foreign Service, with streamlined referral/vetting procedures; increased emphasis on talent acquisition and diversity and inclusion programs; enhanced professional and leadership development training, better coaching and mentorship programs; rationalized bureaus, deputy assistant secretary positions and special envoys; and expanded and enhanced shared service models.

These internal reforms were all designed to fuel performance and productivity by reducing internal clutter and complexity and focusing on external goal delivery. All took a back seat during the extended hiring freeze and workforce reduction exercise. In short, State lost time and momentum. Instead it devotes staff power to the “FOIA surge” (whittling down the backlog of Freedom of Information requests), widely perceived as an exercise to drive people out by displacing them to tasks incommensurate with their diplomatic skills and experience, while higher priority national security objectives are underserved.

The stated objective of the TII is to “improve efficiency, effectiveness and accountability” and to give staff more fulfilling and rewarding careers. Surveys have consistently shown that employees are “fulfilled” when given responsibility to carry out well-articulated policy in furtherance of U.S. national security. Instead, Sec. Tillerson walled himself off from employees and embarked on an exercise that degraded rather than boosted operational and diplomatic capacity. Fewer employees and lower budgets rarely produce great results in a diplomatic arena where intractable problems bedevil policymakers and initiative, judgment and expertise are at a premium.

A more strategic approach would be to aim for responsibility (empowering people and rewarding initiative and judgment); effectiveness (defining and successfully driving policy outcomes that advance U.S. values, interests and goals); and efficiency (reshaping programs and processes to focus on goal delivery, not merely internal coordination). Each of these requires an infusion of capital—human and financial.

The State Department’s mission is quite straightforward: to advance and safeguard American security and promote American interests and values worldwide through diplomacy; to achieve national goals without putting people and treasure at risk through military action; to persuade others to work with and for us in common cause. As in business, certainty and predictability are valued in diplomacy. Here, predictability generates credibility and reliability, which, in turn, generate trust and cooperation. One of America’s greatest strengths has been to serve as model and example.

It is true that disruptions can and do produce short-term gains. But they are rarely a durable foundation for long-term, relationship-based success. With a reduced U.S. foreign affairs budget, dispirited employees and a cramped vision of U.S. leadership, many of America’s adversaries and rivals see retreat and retrenchment, spiked with bluster about military force and economic threats. Little wonder that friends and allies now question the value of America’s word or loyalty.

It is said that the one thing other countries dislike more than American leadership is the absence of American leadership. America may be losing its unique capacity to inspire.

Looking Ahead

The new Secretary of State can set the department on a firmer foundation and truer course. It will not take much to generate energy from the workforce. It’s not necessary to undo the prospective reforms. It is necessary to validate, integrate and fund strategic priorities. Cut clutter and complexity; don’t mistake motion for movement; and don’t confuse internal coordination for external goal delivery. Invest in people.

State Department and USAID employees are as capable, determined and skilled as their colleagues in other national security agencies. They value leadership. They want to know that the Secretary’s team values them—people first, mission always—and that it will look to have the right people in the right places at the right time with the right resources, support and protection to carry out the mission.