America’s Overlooked Diplomats and Consuls Who Died in the Line of Duty

A discovery in a cemetery in Hong Kong spurred a quest to find the names of U.S. diplomats whose ultimate sacrifice remained unacknowledged.

BY JASON VORDERSTRASSE

The AFSA Memorial Plaques in the C Street lobby of the State Department, which were unveiled in 1933 and have been updated since, will be expanded to accommodate the names of diplomats, mostly from the 19th century, whose death in the line of duty was discovered recently.

AFSA / Shawn Dorman

In late September 2009, I took a two-hour ride on the Long Island Railroad to Southampton, New York, and then walked over to the North End Burying Ground. I took the lengthy trip to see the grave of Robert Sterry, one of the few 19th-century U.S. consuls who died in the line of duty whose grave is in the United States. The trip continued my long-standing interest in these overlooked diplomats, which began during my 2007-2008 assignment in Hong Kong (see “Russ and I,” June 2009 Foreign Service Journal).

Sterry, who served as consul in La Rochelle, France, starting in 1816, perished in the wreck of the scow Helen off Long Island on Jan. 17, 1820. Sterry had joined the Consular Service after seven years in the U.S. Army, during which he fought in the War of 1812. His request to President James Madison for a consular appointment came with the endorsement of Brigadier General Alexander Macomb. Although records are sparse, Sterry seems to have had an adventurous spirit, having moved to the Louisiana Territory following his graduation from what would eventually become Brown University. Hailing from a well-connected Rhode Island family, he had made the move bearing a letter of introduction from President Thomas Jefferson.

While in Louisiana, Sterry wrote an article criticizing the territorial governor, William C.C. Claiborne. Claiborne’s brother-in-law and private secretary, Micah Lewis, then challenged Sterry to a duel. Sterry killed Lewis in the duel, shooting him in the chest. Sterry’s son-in-law, Ferdinand Du Fais, later served as consul at Le Havre. His grandson, John Du Fais, became a New York architect of some renown.

During my assignment in Hong Kong, I found three consuls who had died in the line of duty but were not recognized on the AFSA Memorial Plaques in the C Street lobby of the Truman Building. I realized that there are likely many others, especially those from the 19th century. The plaques were unveiled in 1933, and I was surprised to learn that the names on them were the result of research conducted by AFSA; the Department of State kept no records of the diplomats or consuls who had died in the line of duty. In most cases, the only way to learn if someone died while employed by the State Department was to look at the Card Records of Appointments Made, which show the dates of service of consuls or diplomats, organized by geographic location. Though at the time of the plaques’ creation AFSA had the advantage of closeness in time to the many diplomats and consuls who had died during the 19th century, it did not benefit from modern research tools.

I was surprised to learn that … the Department of State kept no records of the diplomats or consuls who had died in the line of duty.

My own research has primarily relied on Google Books and the ProQuest Historical Newspapers database, using search terms like “U.S. Consul Dead” or “U.S. Consul Died.” Unfortunately, a name often requires further research, as it was common for newspapers to misspell names or refer to people as consuls even if they never officially held that title. The Library of Congress’ online resource A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates is particularly helpful in finding Senate nomination and confirmation dates, as well as for its frequent references to replacing “deceased” consuls. The State Department’s consular cards have been retired to the National Archives; researchers can consult them there (see Card Record of Appointments Made, 1776-1960 [RG 59 Entry A1-798]). Walter Burges Smith’s book, America’s Diplomats and Consuls of 1776-1865: A Geographic and Biographic Directory of the Foreign Service from the Declaration of Independence to the End of the Civil War, also has a very useful list of consular posts for the early 19th century.

The Ralph Bunche Library at the Department of State has been particularly helpful to this research. In addition to the ProQuest Historical Newspapers database, it has a great collection of books on diplomats. To my surprise, its collection includes at least three books on diplomats who have been overlooked on the plaques: Samuel Shaw, Henricus Heusken and Edward Ely. Shaw is described in some detail in Peter Eicher’s recent book Raising the Flag: America’s First Envoys in Faraway Lands (2018), and his published diaries are in the library. Ely’s diaries, published as The Wanderings of Edward Ely (1954), include a postscript explaining how he died of dysentery in Bombay (Mumbai) in 1858. Heusken, secretary at American outposts in Japan—both Shimoda and Edo (Tokyo)—died at the hands of anti-foreigner samurai; his activities in Japan are described in amazing detail in Oliver Statler’s Shimoda Story (1969).

Violence, Accidents and Changing Criteria

A portrait of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, the “Hero of Lake Erie” during the War of 1812, who died of yellow fever in 1819. Appointed Special Diplomatic Agent, he had been in Venezuela to negotiate anti-piracy agreements with President Simon Bolivar. On the return trip, he contracted the disease and died shortly before reaching Port of Spain.

U.S. Naval Academy Museum Collection

Other overlooked consuls I discovered include Henry Sawyer, who served as consul in Paramaribo, Suriname, for 23 years. A sailor killed Sawyer on May 7, 1877, after Sawyer attempted to take him into custody. During the Civil War, Sawyer played a role in the near capture of the Confederate privateer Sumter, captained by Raphael Semmes. Semmes, who captured several ships off the coast of South America in late 1861, stopped in Paramaribo to obtain coal. Sawyer attempted to purchase all the coal in the port. Although he failed in this endeavor, he did manage to rent or buy almost all available small ships, making it very difficult for Semmes to load the coal he purchased. As such, Semmes was delayed in port for more than a week as opposed to the expected few hours. Sawyer used this time to contact the U.S. Navy, which had a steamer in nearby Cayenne; but because of what the Chicago Tribune called “cowardice or treachery,” the ship did not respond, and Semmes escaped. In the meantime, Sawyer successfully rescued Semmes’ personal slave.

Violence also claimed the lives of William Baker and William Stuart. Baker served as consul in Guaymas, Mexico, but died in Mazatlán on Dec. 20, 1862, after being attacked by what the contemporary press called “Apaches.” Stuart, who served as vice consul in Batum, Russia (now Batumi, Georgia), died after being shot by an unknown assailant on May 20, 1906. Like many consuls in the 19th century, Stuart represented multiple countries’ interests simultaneously, in this case Great Britain in an acting capacity. Local authorities arrested two men for the murder, but the reason for the killing was never conclusively determined.

Accidents also killed several overlooked consuls. Allen Francis, consul to St. Thomas and Port Stanley in Ontario, Canada, was present in the former city on Aug. 4, 1887, the date of the largest train disaster in the history of the southwest region of that province. Two trains collided, killing 13 people. Francis, who was apparently investigating the crash, died after being struck by fire department equipment.

In the post–World War II era, AFSA criteria for inclusion on the plaques did not include airplane or automobile crashes, but the criteria were changed periodically (see John Naland, “The Foreign Service Honor Roll,” May 2020 FSJ), and in recent years several diplomats who died in such disasters have been added. Of those previously overlooked, George Atcheson Jr. is the most prominent. At the time of his death in 1947, Atcheson served as an adviser to General Douglas MacArthur in occupied Japan and was on his way to Washington, D.C., when his plane crashed 110 miles west of Oahu. Apparently, the pilots had mistakenly set the throttle in the wrong position, and the aircraft ran out of fuel.

According to Time magazine, his last words before the crash were, “Well, it can’t be helped.” Atcheson had previously served as chargé in China during the war and its immediate aftermath, where he was viewed as an ally of John Service and other Foreign Service officers who questioned the staying power of Chiang Kai-shek. After his death, Atcheson’s son, also named George, participated in one of the first underwater demolition attacks in the Korean War as part of a team of swimmers that attacked a train bridge near Yeosu.

Others who died in airplane crashes included Carlin Treat, who died in Morocco on Oct. 10, 1946, on his way to his first post, Casablanca, and George Henderson, consul in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, who died in Shannon, Ireland, on April 15, 1948, while en route back to Washington, D.C., for consultations. The most prominent overlooked victim of an automobile crash is probably Henry H. Ford, consul general in Frankfurt, who died in an accident on the autobahn in 1965 while traveling back to his post from Bonn.

Disease Took the Biggest Toll

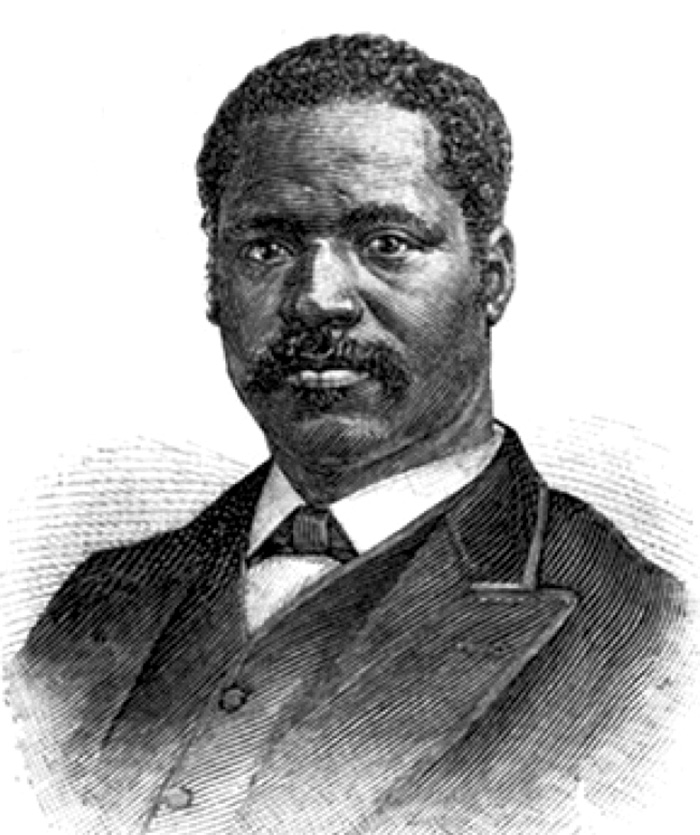

MOSES A. HOPKINS

Tropical Fever – Liberia 1886

Moses Aaron Hopkins was born into slavery in Virginia on Dec. 25, 1846. During the Civil War he worked as a cook in Union Army camps. After learning to read at age 20, he graduated from Lincoln University near Oxford, Pennsylvania, and went on to become the first Black graduate of Auburn Theological Seminary in Auburn, New York. He later settled in Franklinton, North Carolina, where he established a church and a school.

Hopkins was appointed U.S. minister (ambassador) to Liberia in 1885. He died there of “African fever” on or about Aug. 3, 1886. He was one of four U.S. ministers to Liberia who died of tropical disease between 1882 and 1893.

Moses Hopkins was one of the most recent discoveries of an overlooked diplomat, but this brief biographical note is exemplary of the compelling stories behind the new names for the Memorial Plaques.

—John K. Naland

Of course, like most of those commemorated on the plaques in the 19th century, the vast majority of the overlooked consuls and diplomats died of disease. Most famously, yellow fever claimed the life of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, hero of the War of 1812, who had status as a Special Diplomatic Agent. Perry met with Simon Bolivar, then president of the Third Republic of Venezuela who became the first president of Gran Colombia, during the Congress of Angostura. That eventually led to the proclamation of an independent Gran Colombia, which went on to become the independent states of Colombia, Ecuador, Panama and Venezuela. Perry convinced Bolivar to reduce the number of privateer commissions being issued by the republic of Venezuela; some unscrupulous individuals used these commissions to engage in piracy against U.S. shipping. Five of Perry’s crew died in Angostura (now Ciudad Bolivar, Venezuela), but Perry himself only came down with the disease while traveling to Port of Spain. The disease moved quickly, killing him six days after he first showed symptoms.

Yellow fever also claimed the lives of John Howden, consul in Bermuda, who died on Sept. 11, 1853; James Tobut, consul at St. Thomas, then part of the Danish Virgin Islands, who died on Dec. 26, 1858; William Little, consul in Panama City, who died on Jan. 29, 1867; Louis Prevost, consul in Guayaquil, who died on May 23, 1867; and Elphus Rogers, consul in Veracruz, Mexico, who died on Aug. 1, 1881. In Brazil, both William Stapp, who passed away on April 13, 1860, and William R. Williams, consul in Pará, who died on Sept. 25, 1862, were felled by the disease.

Ailments referred to as “tropical disease,” “tropical fever” or merely “fever” also claimed the lives of several consuls and diplomats. As mentioned previously, Consul to Canton (Guangzhou) Samuel Shaw died at sea on May 30, 1794, near the Cape of Good Hope. William Tudor, chargé d’affaires in Rio de Janeiro, died of “fever” on March 9, 1830. Richard Belt, consul in Matamoros, died of “epidemic fever” on Oct. 11, 1844. Hector Ames, consul in Acapulco, Mexico, died of “fever of the country” on May 16, 1853. Samuel Collings, consul in Tangier, at the time one of the most important posts in the world, died on June 15, 1855, from “African fever.” Consul to La Unión, El Salvador, William McCracken died from “congestive fever” on July 7, 1857. Frank Frye, consul in Ruatán (now Roatán), Honduras, died of “fever” on Feb. 10, 1879. Seth Ledyard Phelps, minister to Peru, died of Oroya fever on June 24, 1885. Moses Hopkins, minister to Liberia, died of “African fever” on Aug. 3, 1886.

One of the pioneering African American diplomats, Alexander Clark, also died of fever, while representing the United States as minister in Monrovia on May 31, 1891. A native of Pennsylvania, Clark had settled in what became Muscatine, Iowa, where he worked as a barber and operated a lumberyard. At the outset of the Civil War, Clark, as a sergeant major, helped organize the 1st Iowa Volunteers of African Descent. Clark and his son both graduated from the University of Iowa law school, the first African Americans to do so. Clark also operated the Chicago Conservator newspaper, speaking out on civil rights issues. President Benjamin Harrison nominated him for the overseas diplomatic position on Aug. 16, 1890, but Clark died in Liberia less than a year later.

Like most of those commemorated on the AFSA plaques in the 19th century, the vast majority of the overlooked consuls and diplomats died of disease.

In addition to Edward Ely, dysentery claimed the lives of James Thornton, chargé d’affaires in Callao, Peru, on Jan. 25, 1838; Alexander McKee, consul in Panama, on Sept. 3, 1865; Edward Conner, consul in Guaymas, Mexico, on July 16, 1867; Hiram Lott, consul in Managua, on June 15, 1895; and John Carter Ingersoll, consul in Colón, Panama, on June 6, 1903. Cholera felled William Venable, minister to Guatemala, on Aug. 27, 1857; vice consul John Amory in Calcutta (Kolkata) on July 1, 1860; consul William Irvin in Amoy (now Xiamen), China, on Sept. 9, 1865; and vice consul Jose Casagemas in Barcelona in early November 1865. Typhoid fever killed Daniel Brent, consul in Paris, on Jan. 31, 1841. And smallpox ended the lives of John T. Miller, vice consul in Rio de Janeiro, on July 28, 1887; Thomas Gibson, consul in Beirut, on Sept. 20, 1896; and Thomas Newson, consul in Málaga, Spain, on March 30, 1893.

Turning to those who met a watery demise, we find that, unfortunately, Robert Sterry is not the only overlooked consul to die in a shipwreck. James Holden, commercial agent at Aux Cayes (now Les Cayes), Haiti, was lost at sea in 1827. John Miercken, consul in Martinique, boarded the Lafayette in September 1832, but the ship never arrived at its destination and was presumed sunk. Isaiah Thomas III, appointed as consul to Algiers, departed New York on the Milwaukee on Feb. 21, 1862, after being nominated by President Lincoln. Thomas, who had previously edited the Cincinnati American, and three of his children were lost at sea.

AFSA has undertaken a project to recognize these individuals and other diplomats whose death in the line of duty has not been acknowledged. In August 2020, the AFSA Governing Board approved funding to inscribe the names of the early diplomats and consular officers on new plaques in the C Street lobby, hopefully in time for the association’s annual memorial ceremony in May 2021. With that, their service to their country will finally be recognized, and we will no longer have to refer to them as “overlooked.”

PARALLEL EFFORTS

Others became involved in the search for overlooked diplomats, as well.

Consular Card Project. FSOs Lindsay Henderson and Kelly Landry, while working in the Office of Policy Coordination and Public Affairs of the Bureau of Consular Affairs, conducted their own search for early colleagues who died in circumstances distinct to overseas service but are not honored on the AFSA Memorial Plaques.

Over many off-duty hours during 2019-2020, they reviewed each of the approximately 6,500 “consular cards” on which the State Department tracked overseas assignments of consular officers and diplomats from the 1790s to the mid-1960s. On those mostly handwritten index cards, they found 762 annotations of death at post. For each case, they queried a large online database of U.S. newspapers dating back to the 1700s to attempt to determine the cause of death (which is rarely noted on consular cards).

They found contemporary newspaper reporting on approximately half of the deaths. Those reports documented 11 colleagues who had died between 1826 and 1942 under circumstances qualifying for inscription on the plaques. The AFSA Governing Board approved adding them in June 2020.

Foreign Service Specialists. Consular cards rarely record assignments of employees who today are categorized as Foreign Service specialists. But AFSA Governing Board member John Naland discovered that the Bureau of Diplomatic Security had posted documentation on its website about Foreign Service diplomatic couriers who died overseas in accidents during official travel. One, Seth Foti, who died in 2000, was already on the AFSA Memorial Plaque. But four others, with dates of death between 1945 and 1963, were not. The AFSA Governing Board approved their inscription in May 2020.

Researching further, Naland discovered that Foreign Service secretary Nicole Boucher also died in a 1963 crash. She was 28 years old and was returning to the United States after completing her first assignment when the airliner that she and diplomatic courier Joseph P. Capozzi were flying in crashed into Mount Cameroon, near Douala, Cameroon. The AFSA Governing Board approved her inscription in June 2020.

—J.V.

Read More...

- “The Foreign Service Honor Roll,” by John Naland, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2020

- AFSA Memorial Plaque List

- Virtual AFSA Memorial Plaque