The Foreign Service Honor Roll

U.S. diplomats are on the front lines of America’s engagement with the world. Here is the history of AFSA’s work to pay tribute to the many who sacrificed their lives in the line of duty.

BY JOHN K. NALAND

AFSA President Barbara Stephenson (at podium), with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (far left), addresses Foreign Service colleagues and family members of the deceased at the ceremony on May 4, 2018.

AFSA / Joaquin Sosa

Behind each of the 250 names inscribed on the AFSA Memorial Plaques in the Department of State’s diplomatic entrance is the story of a colleague who made the ultimate sacrifice for our nation. This article does not recount those heroic, tragic or other inspirational stories; rather, it tells the story of the plaques themselves—their origin nearly a century ago, and the controversies in succeeding decades about who should be honored on them.

Origins

The U.S. Foreign Service was created on July 1, 1924, when the Rogers Act of May 24, 1924, took effect, merging the previously separate consular and diplomatic services. AFSA was founded one month later when the six-year-old American Consular Association disbanded, and its members joined with their diplomatic colleagues to form AFSA.

In January 1929, members of the young organization read in the American Foreign Service Journal (as this magazine was named until 1951) that the AFSA Executive Committee (the governing board of the day) had received a proposal to create an honor roll to be displayed at the Department of State. This would memorialize all American consular and diplomatic officers who had died under tragic or heroic circumstances since the founding of the republic. The proponent, whose name was not given, listed 17 names for inscription. The Executive Committee did not explicitly endorse the proposal, but did invite members to suggest additions or corrections.

Letters came rolling in, and four months later the Journal published 29 more names. It also issued an invitation for additional submissions, and in February 1932 published an updated and consolidated list containing 53 names.

Meanwhile, the Executive Committee took until March 1930 to appoint a committee to move forward on what they called the Memorial Tablet project. Its members were Journal Editor Augustus E. Ingram, Foreign Service Officer Pierre de Lagarde Boal and retired Consul General Horace Lee Washington.

Completion took another three years. First, AFSA had to obtain approval from Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson. Then Congress had to pass a joint resolution, signed by President Herbert Hoover, authorizing placement of the AFSA-owned memorial on government property. Next, AFSA had to raise donations to cover the $1,738.89 construction cost (around $34,000 in today’s dollars). Finally, after noted architect Waddy B. Wood designed a tablet of Virginia greenstone mounted in a framework of white Alabama marble, the U.S. Commission on Fine Arts approved the design.

As work progressed, the Executive Committee grappled with a question that would arise again and again: Whom, exactly, should the tablet honor?

As work progressed, the Executive Committee grappled with a question that would arise again and again: Whom, exactly, should the tablet honor? The committee discarded a proposal to honor all diplomatic and consular officers dying abroad, which would have included those whose deaths (such as by heart attack or during a pandemic like the 1918-1920 Spanish flu) were not due to the distinctive risks of overseas service. Instead, the committee settled on honoring those diplomatic and consular officers who died on active duty overseas “under heroic or tragic circumstances.”

That standard was vague, but the U.S. House of Representatives report that recommended placing the memorial on government property explained that it would honor those dying in natural disasters, from tropical diseases, during official travel and due to violence. Those criteria are apparent in the first 65 names inscribed on the plaque. Forty-two died of contagious diseases encountered overseas, such as yellow fever and malaria. Seven were lost at sea traveling to or from their post of assignment (the first listed name, William Palfrey, elected by the Continental Congress as consul in France, died in 1780, lost at sea en route to his post). Six died in natural disasters, such as earthquakes and hurricanes at post. Four died while attempting to save a life. Three were murdered—in Bogotá, in Tehran and in Andixcole (now Andasibe), Madagascar—while two died of “exhaustion.” Another, Joel Barlow, was caught up in the maelstrom of Napoleon’s 1812 retreat from Moscow, and died of pneumonia in the bitter cold of a Polish winter.

The Memorial Tablet’s unveiling took place on March 3, 1933, in the north entrance of the State, War and Navy Building (known today as the Eisenhower Executive Office Building) next to the White House. Secretary Stimson, who had donated the American flags and their brass bases that flanked the tablet, presided as 10 senators and congressmen looked on.

The tablet, said the Secretary, “should serve as a means of bringing home to the people of this country the fact that we have a Service in our Government devoted to peaceful intercourse between the nations and the assistance of our peaceful commerce which, nevertheless, may occasionally exact from its servants a sacrifice the same as that which we expect from our soldiers and our sailors.” The memorial’s second purpose, he said, is to “serve in the development in our present Service—the successors of the men whose names are recorded here—of that same spirit of devotion and sacrifice which those men evidenced.”

Before the ceremony ended with a Navy bugler sounding “Taps,” Secretary Stimson noted that there were undoubtedly other American diplomats and consular officers who had died in the performance of their duties in distant lands. But the facts of their deaths “have not survived the thickening veil of time.” Indeed, later research has revealed many more such cases (see below).

Second Thoughts

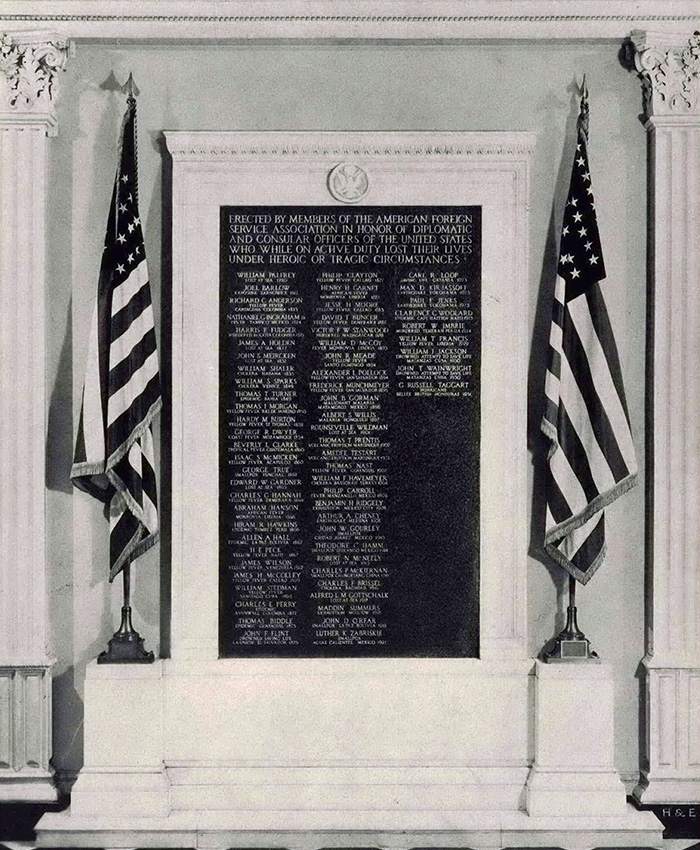

The AFSA Memorial Tablet was unveiled on March 3, 1933, with Secretary of State Henry Stimson presiding. This photo of the tablet appeared in the November 1936 photographic supplement of the American Foreign Service Journal.

AFSA / FSJ Supplement November 1936

As the 1930s progressed, new AFSA leaders interpreted the criteria for inscription differently. In 1938, the Executive Committee declined to add the name of a vice consul who had died of malaria in Colombia. In August of that year, the Journal printed a full-page statement from Secretary of State Cordell Hull, who appeared to criticize that decision. Taking note of the tablet as “an appropriate and impressive reminder of what the work of the Service involves,” Hull said that the consul’s death “in the performance of his duties as a member of the Foreign Service ... deserves more notice than it has received.”

Despite the Secretary’s appeal and the original congressional intent in authorizing the memorial, AFSA Executive Committees in the late 1930s and early 1940s continued to reject candidates for inscription who died from tropical diseases and during official travel. They added only two names (one murdered and the other killed in an earthquake), reasoning that honoring those whose deaths were not “peculiarly” heroic or tragic “might tend to diminish the profound significance” of the memorial. During the 1940s AFSA began using the term “Memorial Plaque.”

In 1946 the Executive Committee sought advice from AFSA’s membership on two proposed changes to the criteria. The first would expand eligibility beyond Foreign Service officers to include Foreign Service staff members (today’s Foreign Service specialists). This was prompted by passage of the Foreign Service Act of 1946, which accorded Americans working overseas in clerical and administrative positions full professional status as members of the U.S. Foreign Service. The second would explicitly exclude those who died abroad of tropical diseases (with exceptions in extraordinary cases) or of other causes that did not constitute “peculiarly heroic circumstances in the performance of acts abroad beyond and above the accepted high standard of duty in the Foreign Service.”

AFSA’s annual general meeting in 1948 “revealed considerable divergence of opinion,” the July 1948 American Foreign Service Journal reported, but adopted the two changes. In a 1949 report to members, AFSA noted that it had approved the inscription of only one of 15 names of Foreign Service members who had died abroad under tragic circumstances since 1942. After the State Department moved to new headquarters at 21st Street and Virginia Avenue NW in 1947, the plaque followed in 1954. Only six additional names had been inscribed since 1933. One was the first Foreign Service specialist on the plaque: Robert Lee Mikels, who died trying to save colleagues during a fire at Embassy Pusan in 1951. In 1961 the plaque was moved to its current location in the west end of the C Street lobby when the New State Extension completed today’s Harry S Truman Building. Open space remained for additional inscriptions.

The names of 39 colleagues killed in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia between 1965 and 1975 filled that open space, but only after a mysterious delay. Even as the death toll mounted in Southeast Asia, no inscriptions were made between 1963 and 1972. “The extended delay,” as the late David T. Jones recalled in the October 1999 FSJ, “engendered suspicions among FSOs that the department was attempting to conceal the extent of its losses from a rank and file (and a larger public) increasingly skeptical of the purpose and value of the war effort.” It is also true, however, that AFSA had had to go through the steps required to erect a second plaque to hold all the names.

AFSA put up the second plaque in 1972 at the east end of the C Street lobby, and took that opportunity to revise the criteria to require “heroic or other inspirational circumstances” in place of “heroic or tragic circumstances.” The exchange of one set of vague criteria for another had little practical impact on subsequent inscriptions.

The new plaque responded to the scourge of war, but it was the scourge of terror that filled it. The addition in March 1973 of the names of two FSOs assassinated by terrorists in Sudan drew President Richard Nixon to become the first, and so far only, president to speak at the plaques. The next year, AFSA President Thomas Boyatt held the first of what would become annual memorial ceremonies at the plaque on Foreign Service Day.

After 1975, terrorism accounted for the deaths of most of those whose names were added to the plaque. By 1983, following the addition of 13 killed in the bombing of U.S. Embassy Beirut, the 11-year-old second plaque was nearly three-quarters filled.

Changing Criteria

At the May 2, 2014, Memorial Ceremony, AFSA honors those who lost their lives while on active duty.

Bob Burgess

Before 1982, eligibility for inscription was limited to Foreign Service members, Marine security guards, U.S. military personnel assigned to the U.S. Agency for International Development in Vietnam and employees of the Central Intelligence Agency under State Department cover at the time of death (see below). But after terrorists murdered Lieutenant Colonel Charles Ray, assistant army attaché at U.S. Embassy Paris, the AFSA Governing Board expanded the plaque criteria to include all Americans serving under chief-of-mission authority.

In making that change, it is unclear if the Governing Board considered the fact that, since World War II, American citizen staffing at U.S. embassies had shifted from being mostly Foreign Service to being mostly employees of other agencies. Thus, only 16 of the 43 names added to the AFSA plaques during the remainder of the 1980s were members of the Foreign Service. Those 43 names filled the remaining spaces on the second plaque in 1988, and the roll of honor spilled over to four side panels installed in 1985.

The new plaque responded to the scourge of war, but it was the scourge of terror that filled it.

During the 1990s, victims of terrorism continued to account for most additions to the plaque. Eight names were inscribed in 1998 following the bombing of U.S. Embassy Nairobi. In 1996 many AFSA members objected to adding political appointee Ronald Brown’s name after his death on an overseas trip, but the AFSA Governing Board did so judging that as secretary of the Department of Commerce, Brown qualified as the head of a Foreign Service agency.

As the new millennium began, AFSA had accumulated numerous plaque nominations for Foreign Service members who had died in the line of duty overseas. These nominations would have met the original 1933 criteria for inscription, but did not meet the criteria adopted in 1948. Pressure built from former colleagues to honor them nonetheless, and in 2001 the Governing Board restored authorization for personnel who died overseas “in the line of duty.” AFSA invited members to suggest qualifying cases, and that resulted in the addition of 29 names in three years, all State Department or USAID employees with dates of death ranging from 1959 to 2000.

Iraq and Afghanistan

The next major change in plaque criteria took place in 2006. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had dramatically increased the number of American civilian employees in harm’s way overseas. In war-zone Iraq, for example, FSOs led dozens of Provincial Reconstruction Teams on which Foreign Service members were a small minority. The AFSA Governing Board became concerned that members of the Foreign Service could, in time, become a small minority of those honored on the plaques. Were that to happen, it would undermine the two purposes articulated by Secretary Stimson in 1933: to increase public appreciation for the sacrifices of the Foreign Service, and to inspire a spirit of sacrifice in future generations of Foreign Service members.

The Governing Board also noted that many agencies or employee groups representing other federal employees who work at embassies—including defense attachés, Marine security guards, Drug Enforcement Administration agents and Federal Bureau of Investigation agents—have their own memorial walls. Indeed, within sight of the AFSA Memorial Plaques in the C Street lobby are nearly a dozen other memorials (see below).

So the Governing Board reversed the 1982 criteria and limited inscription to “members of the Foreign Service and to U.S. citizen direct-hire employees of the five foreign affairs agencies serving the government abroad.” Exceptions could be made only in “compelling circumstances.”

But world events soon prompted yet another revision. In 2007, civilians in a variety of employment categories from the foreign affairs agencies surged into Iraq, with staffing peaking in 2010. And between 2009 and 2012, civilian employees surged into Afghanistan, many of them temporary hires on non–Foreign Service appointments. The Governing Board became concerned such individuals might come to dominate plaque inscriptions; and, in fact, five of the seven names added to the plaques from Iraq in this period were not Foreign Service members. In 2011 the Governing Board limited inscription to members of the Foreign Service, with other employees considered only in “exceptional or heroic circumstances.” In 2014, the Governing Board eliminated all exceptions.

Today and Tomorrow

As of this writing, the AFSA Memorial Plaques contain 250 names. Forty-eight additional “historical” names have been approved for inscription. The two original plaques and three side panels are full, and space remains on the fourth side panel for just eight names. While we can hope that no new names will need to be inscribed for many years, history suggests otherwise. AFSA is currently coordinating with the Department of State’s Bureau of Administration with the goal of adding additional plaque space in time for the annual AFSA Memorial Plaque ceremony in May 2021.

Parting the “Veil of Time”

–Historical Names–

In 2007, Jason Vorderstrasse was an entry-level FSO serving in Hong Kong. When a colleague mentioned visiting a local cemetery where he had seen the grave of a U.S. diplomat whose name was not inscribed on the AFSA Memorial Plaques, Vorderstrasse was intrigued. He visited the cemetery, found the gravestone and conducted internet and archival research that established that Consul F. Russell Engdahl had died in 1942 while a prisoner of the Japanese military. Additional research identified two U.S. envoys who had died of disease in Macau in 1844. Vorderstrasse nominated all three for inscription on the plaques. Their names were added on Foreign Service Day 2009.

Vorderstrasse continued his research. In a March 2014 Journal essay, he reported documenting an additional 32 names of earlier diplomats and consular officers who died overseas due to tropical diseases, violence or accidents while in official transit.

By December 2019, the number of names Vorderstrasse documented had risen to 39, with nine additional historical names documented by other AFSA members. The AFSA Governing Board voted to add those 48 names “if and when funding is available” to install and inscribe additional marble plaques. For now, the names are memorialized on a virtual plaque on the AFSA website at afsa.org/memorial-plaques.

CIA Employees on the AFSA Memorial Plaques

Of the 133 employees honored with stars on the Memorial Wall at CIA headquarters, the names of 93 have been publicly acknowledged, but often only years after their deaths. In more than 20 cases, persons later recognized by the agency as CIA employees were working under State Department cover at the time of their deaths and were inscribed (as State Department employees) on AFSA’s Memorial Plaques.

They include: Douglas Mackiernan (the first CIA officer killed in the line of duty, 1950); Barbara Robins (a CIA officer, and the first woman whose name was inscribed on the AFSA plaques, 1965); eight CIA officers killed in the 1984 bombing of Embassy Beirut; and Tyrone Woods and Glen Doherty, who were killed during the 2012 attack on U.S. government facilities in Benghazi.

Other Memorials

The AFSA Memorial Plaques are not the only memorials displayed at the State Department. In the C Street lobby there are also individual plaques honoring: Foreign Service Nationals killed in the line of duty; Foreign Service family members who died overseas; U.S. Information Agency employees killed between 1950 and 1998, before the agency dissolved in 1999; federal employees who died in an airplane crash during a Department of Commerce trade mission in Croatia in 1996; employees and family members killed in the 1998 attacks on Embassies Nairobi and Dar es Salaam; diplomatic couriers; and military service members killed in the 1980 Iran hostage rescue attempt.

And State’s 21st Street lobby has a memorial to Americans and foreign nationals who died supporting the department’s criminal justice and rule of law assistance programs overseas.

Elsewhere, at USAID headquarters in the Reagan Building in Washington, D.C., the agency’s Memorial Wall contains the names of Foreign Service officers and other employees who died overseas in the line of duty.

—J.K.N.