Larger Than Life: F. Allen “Tex” Harris, 1938-2020

BY STEVEN ALAN HONLEY

One would not expect a 6’7” former basketball player to fit the stereotype of a mild-mannered diplomat, and “Tex” (as Franklyn Allen Harris was universally known) most assuredly did not. Although he was a firm believer in the power of persuasion, throughout his 35-year Foreign Service career Tex stood ready to use his impressive intellect, imposing bulk and booming voice to defend the oppressed and speak truth to power.

“Today a nation is judged by how it treats its own citizens, establishing a new norm in modern diplomacy,” Tex Harris declared in 2013, as he received an award from the United Nations Association for “the use of diplomacy to advance human rights.” An unforgettable mentor as well as a role model for many of those who fought to make President Jimmy Carter’s human rights revolution a reality, Harris will be remembered as a real hero, especially at this particularly troubled time abroad for American democracy and leadership.

Tex Harris was still engaged in that lifelong mission on multiple fronts when he died on Feb. 23 at a hospital in Fairfax County, Virginia. He was 81. Survivors include his wife of 53 years, the former Jeanie Roeder, of McLean, Va.; three children, Scott Harris of McLean, Julie Harris of Falls Church, Va., and Clark Harris of Los Angeles, Calif.; and two grandsons.

Fighting the Good Fight

AFSA President Eric Rubin (left) presents F. Allen “Tex” Harris with the AFSA Achievement and Contributions to the Association Award at the AFSA Awards Ceremony on Oct. 16, 2019.

AFSA / Joaquin Sosa

Franklyn Allen Harris was born on May 13, 1938, in Glendale, California, and grew up in Dallas, where he was an all-state basketball player in high school. His father was a businessman, and his mother had been a model and sales clerk.

After graduating from Princeton University in 1960, Mr. Harris used funds intended for a car purchase to travel around the world for almost three years, meeting a number of diplomats in his journeys. After graduating from law school at the University of Texas, he joined the Foreign Service in 1965.

Tex first served in Caracas, then spent most of the next decade in Washington, D.C., in various positions. But the most famous example of his legendary tenacity came in Argentina, at the height of that country’s “dirty war.”

A group of military leaders had seized control of the government in 1976 after the chaotic two-year presidency of Isabel Perón. President Gerald Ford’s administration initially applauded the junta for the anticommunist stability it purported to represent, but the embassy soon learned of widespread, systematic efforts to stifle dissent through kidnappings, torture and killings.

In October 1977, shortly after Tex arrived in Buenos Aires, the political counselor asked him to pursue what was then a brand-new facet of diplomatic tradecraft: human rights reporting. Tex readily agreed—on the condition that the embassy relax its long-standing restrictions on entry by private Argentines, so that he could interview anyone who wanted to discuss the disappearance (and presumed death) of a relative, friend or colleague.

Tex then printed up business cards and went to Buenos Aires’ central square to hand them out. He worked closely with the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, the renowned advocates for “los desaparecidos,” and invited its members to visit him at the embassy.

“What I did in Argentina was to open the doors and, for the first time, to talk to the people,” Tex told Bill Moyers in a 1984 “Frontline” interview on PBS. As he explained, “This was not an ad hoc, spur-of-the-moment vigilante group, but a concerted program of the military government to eliminate entire groups of people that they deemed to be subversives in their society. There were thousands of people who disappeared without a trace, without a murmur, just a picture on their mother’s dresser.”

Within a few weeks, scores of Argentines were flooding into the embassy daily to report missing loved ones. Tex singlehandedly documented the disappearances of 15,000 people, even as the United States was still characterizing the phenomenon as a mysterious by-product of the right-wing militias’ struggle with left-wing terrorists. In truth, as the stacks of notecards Tex compiled would prove, Argentina’s military leaders had what he called “a clear intention to exterminate” anyone who opposed them. Even children and babies were seized from parents deemed to be dissidents.

At first, U.S. Ambassador Raul Castro and the entire embassy staff applauded Tex’s detailed reporting. And President Jimmy Carter’s administration began signaling its growing disapproval of the junta—one of the first cases of a U.S. president basing critical diplomatic decisions on how a foreign government treated its own citizens. But as bilateral relations chilled, Tex came under increasing pressure, both from the front office and the Argentine government, to stop dwelling on the thousands of victims and put a positive spin on developments.

Instead, he went public, regularly appearing with the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo at their demonstrations against the regime. When the embassy stopped transmitting his cables, Tex used airgrams, memoranda of conversation and formal-informal letters—none of which required front office clearance—to convey his findings and recommendations to State via classified pouch.

Tex Harris, one of the most consequential individuals in AFSA’s history, showed what professional diplomacy can accomplish in the face of internal and external opposition.

One of his reports resulted in the cancellation of a U.S. government loan guarantee worth hundreds of millions of dollars to an American corporation that was to supply turbine manufacturing technology to a front corporation owned by the Argentine Navy—which was carrying out much of the torture and killing. (Embassy Buenos Aires had not previously reported that affiliation to Washington.)

His courageous role during that period has been profiled on TV, in print, online and in AFSA’s 2003 edition of Inside a U.S. Embassy, and has been cited by AFSA and others as a prime example of what professional diplomacy can accomplish in the face of internal opposition.

Tex knew that his performance evaluations would suffer as a result of what his supervisors regarded as insubordination, but he was sanguine about never becoming an ambassador. He was identified for selection-out based on a claim that he was not producing enough reporting—even as the embassy refused to disseminate his cables—but an independent review overturned that finding.

In 1984, AFSA presented Tex with the William R. Rivkin Award for Constructive Dissent by a Mid-Level Officer for the “courage, strength of character and dedication to the Foreign Service” he demonstrated in Buenos Aires. The award specified that Harris displayed not only “physical courage” in the face of credible threats to his and his family’s lives, but “bureaucratic courage to stand up for what was right despite unnecessary obstacles placed in his way.”

And in 1993, with the benefit of 15 years of historical hindsight, the State Department conferred the Distinguished Honor Award on Tex for his reporting from Argentina. The damage was done, however. Although his Foreign Service career would last another 20 years after Buenos Aires, it was effectively stalled.

His commitment to truth-telling continued during a detail to the Environmental Protection Agency in the early 1980s. Tex was the first person Anne Gorsuch, President Ronald Reagan’s Environmental Protection Agency administrator, fired for his efforts as head of the International Activities Office to ban chlorofluorocarbons, which were destroying atmospheric ozone.

Overseas, he served in Durban and Melbourne, his final posting, where he was consul general. He retired from the Foreign Service in 1999.

From Young Turk to “Mr. AFSA”

In announcing his passing, AFSA rightly hailed Tex Harris as “one of the most consequential individuals in the history of the association, and a man who defined the term ‘larger than life.’”

Over the past 50 years, Tex made enormous contributions to AFSA and the Foreign Service. In 1969 he joined with fellow “Young Turks” Lannon Walker, Charles Bray, Herman “Hank” Cohen and others to ensure that American diplomats had a clear voice in establishing the standards for their profession, and that AFSA was an institution that would defend both the Service and its members.

As an attorney, Tex was AFSA’s in-house counsel in the early to mid-1970s. He went on to serve as vice president for the State Department constituency on the Governing Board from 1973 to 1976, during which time he worked with William Harrop and Thomas Boyatt to turn AFSA into an effective union representing all Foreign Service employees. He was instrumental in drafting and negotiating the core labor-management agreements in the foreign affairs agencies, and was one of the four drafters of the 1976 legislation that led to the Foreign Service grievance system.

In 1993, with the benefit of 15 years of historical hindsight, the State Department conferred the Distinguished Honor Award on Tex for his reporting from Argentina.

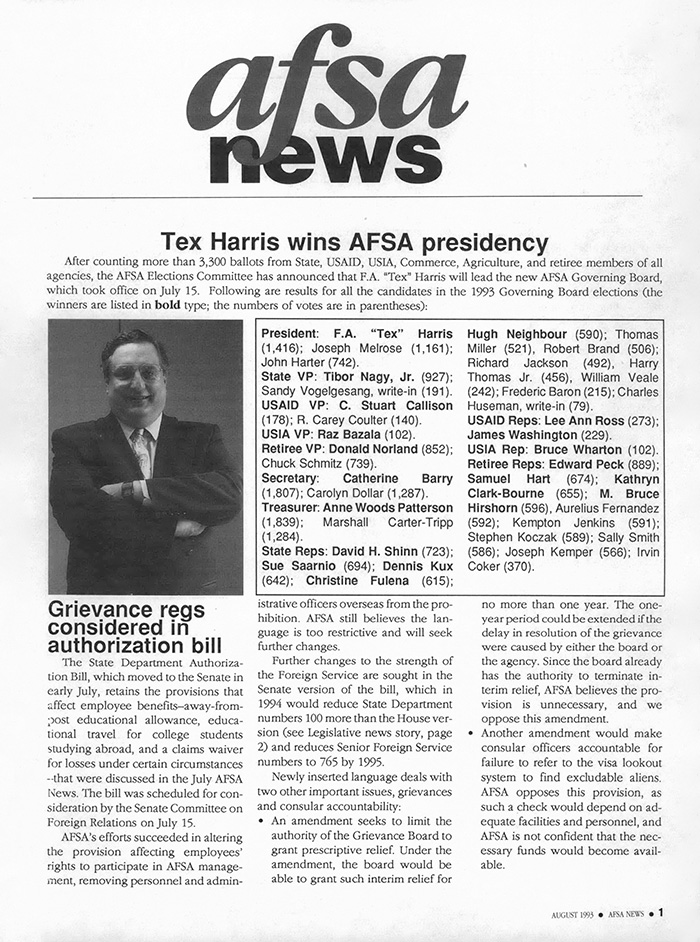

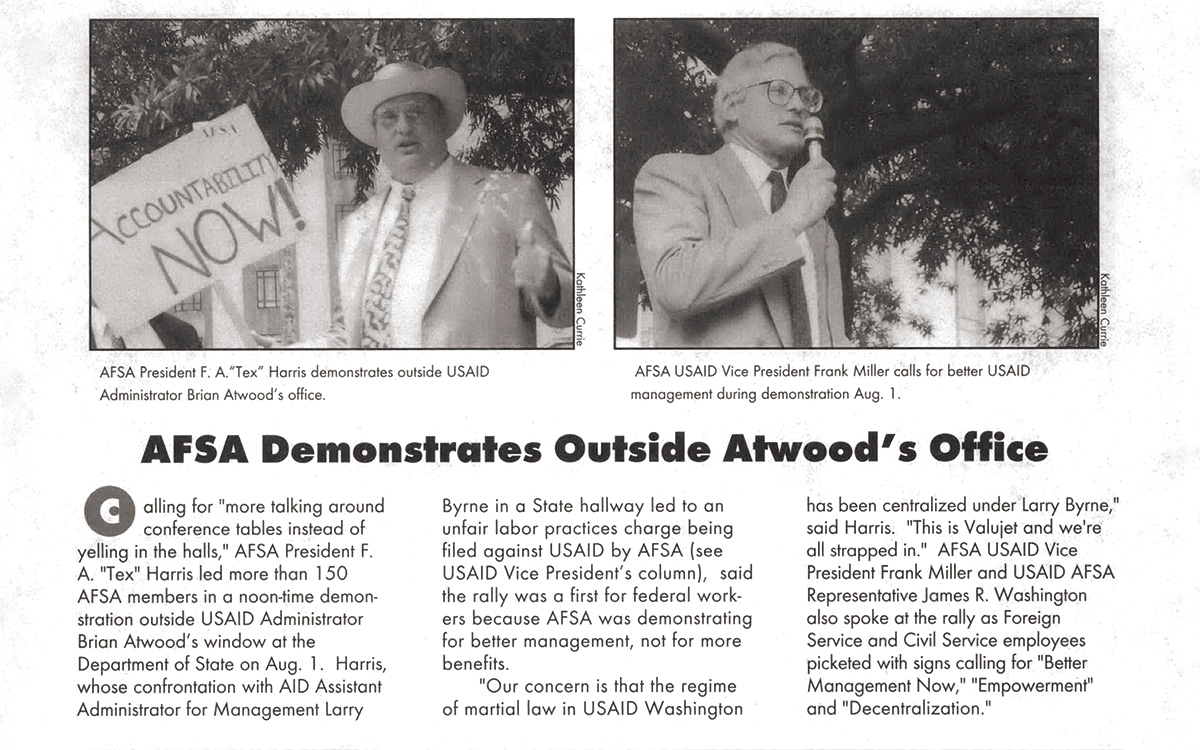

He served two terms as AFSA president, from 1993 to 1997, fighting against reductions in force at USAID, government shutdowns, the appointment of unqualified political ambassadors and major management abuses (such as classifying diplomatic security protective detail agents as “managers” to avoid payment of millions of dollars of overtime). He succeeded in gaining significant benefit increases for service overseas.

After retiring from the Foreign Service in 1999, Tex continued his close involvement with AFSA. In 2000, he was instrumental in the creation of the F. Allen “Tex” Harris Award for Constructive Dissent by a Foreign Service Specialist, to bring the same recognition to specialists for their intellectual courage as the association had been giving Foreign Service officers for more than three decades. The criteria for the Harris Award are phrased in a way that define his life and legacy: “To take an unpopular stand, to go out on a limb, or to stick his/her neck out in a way that involves some risk.”

The AFSA membership elected Tex to multiple terms in the 2000s and 2010s as secretary and as a retiree representative—enabling him to continue contributing to setting AFSA’s agenda and policies.

Continuing to Make a Difference

For many years, Tex ran a one-man listserv, “AFSATEX,” and was active in several of AFSA’s sister organizations that work to advance the interests of the Foreign Service. He served several terms on the board of directors of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, and produced the ADST video/podcast series Tales of American Diplomacy, which screened its first “TAD Talk” episode on C-Span in November 2019. Tex was also the host of the Foreign Affairs Retirees of Maryland and D.C. until his death.

Widely referred to as “Mr. AFSA,” Tex also remained in contact with scores of retired Foreign Service colleagues from the last 50 years—sharing information and connecting them with other colleagues to discuss major issues facing today’s Foreign Service. He was also an active member of the group of former AFSA presidents who advise AFSA and other Foreign Service groups.

In October 2019, AFSA presented Tex with its Award for Achievement and Contributions to the Association, celebrating his half-century of tireless support of AFSA and the career Foreign Service. During the ceremony he gave a typically rousing speech, which had the audience cheering him loudly. It was Tex at his best, and the honor was well deserved.

In recent years, Tex had turned his focus to climate change and climate diplomacy, arguing that the Foreign Service has a critical role in combating global warming under the voluntary National Determined Commitments regime established in the Paris Accords.

“The U.S. Foreign Service will be called on to meet its greatest challenge since the Cold War in convincing elites and general publics in more than 200 nations to ‘ratchet up’ their national voluntary cuts in fossil fuel usage to save the planet from further overheating,” he said. “We have probably already lost the coral reefs, much of the Arctic ice and low-lying areas of Alexandria, Miami Beach and Lower Manhattan to global warming. American diplomacy must lead the way to protect the planet from major damage.”

Never one to shy away from big ideas and actions to match, Tex Harris remained true to himself until the very end.

REMEMBRANCES

Integrity, Compassion, Loyalty

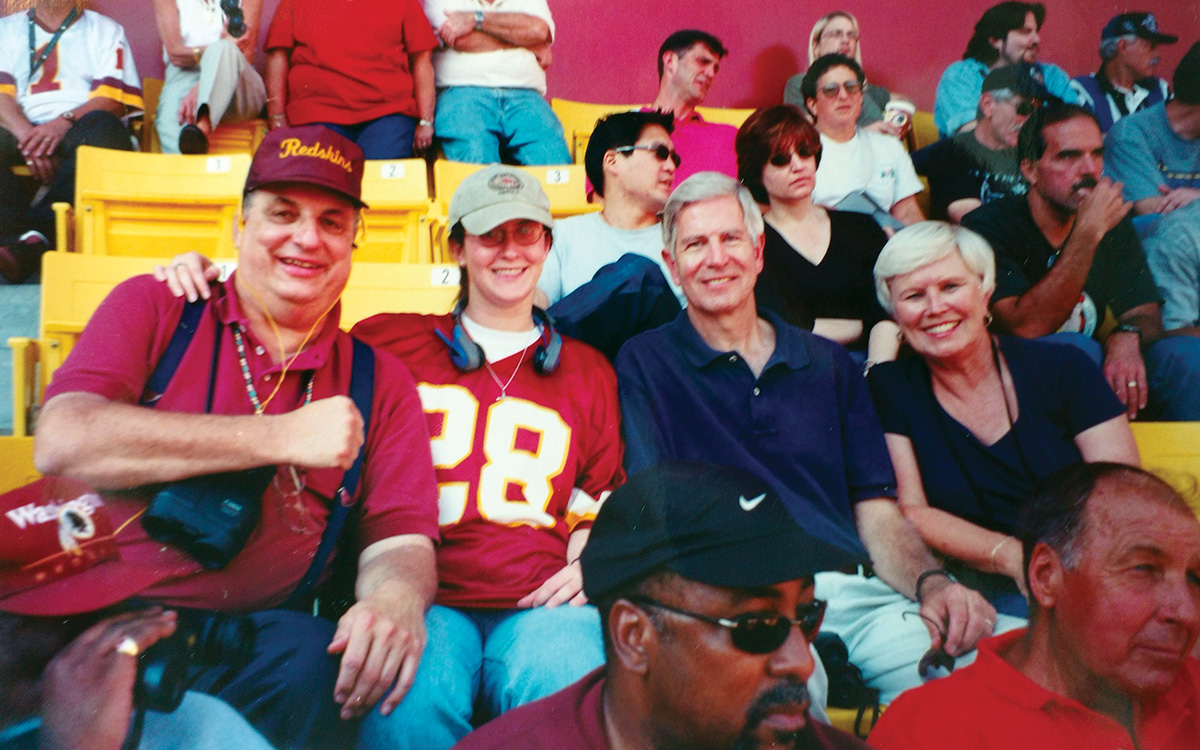

Tex with daughter Julie, and Clyde and Ginny Taylor, at a Redskins game, October 2000.

Courtesy of Clyde Taylor

During Orvis fishing trip on the Shenandoah River with Clyde Taylor, April 2000.

Courtesy of Clyde Taylor

Tex was my oldest, best Foreign Service friend. Almost 52 years ago I was temporarily detailed from within the Economic Bureau to the front office to serve as a staff assistant with Tex. We worked hand in glove and quickly bonded, a bond that grew every time we were both in Washington and became even tighter after we retired. Our career experiences were sufficiently similar—serving mostly in the developing world, with the exception being Australia for both of us. I even had a brief time on the AFSA Governing Board when he was president.

When I reflect on why our friendship prospered, I also ask myself what made him an iconic figure in our professional diplomacy, touching and earning the respect of hundreds. His uncommon values and virtues stand out: integrity, loyalty, intellectual curiosity, compassion and genuine love of people. What for others might have been despairing frustration with bureaucracy or incurable indifference was for Tex a challenge to persuade and co-opt. Whether in difficult places or in leadership of AFSA, Tex was exemplary in dominating an issue, identifying options and mustering support for success. I never knew him to walk away from a problem or be first to leave the negotiating table.

Tex loved to recall actions of our colleagues, the more outrageous the better, which made for memorable lunches. And he was fun. Once, we went fishing at Great Falls, at least that was the goal. As we headed for the riverbank, I constantly “lost” Tex as he “met a new friend” on the trail, exchanging business cards, of course. I had landed a nice bass when he caught up, and heard him out about a new friend who had a factory making pressed wood, which he would later visit. I was about to release my fish when Tex grabbed it for dinner, despite my warning that it had enough mercury to show temperature.

The other fishing story is from the Orvis Fly-Fishing School in Luray. I prize a picture of Tex, in waders, his Texas hat and whatever else came out of his amazing wardrobe, coming toward the guides and me. They just stared at him in disbelief before joining my uncontrollable laughter. Yes, he was a nice version of the abominable snowman, all 6’7’’ of him. I already miss him so very much.

—Clyde D. Taylor

The Advocate

We miss him already.

F. Allen “Tex” Harris had presence, was a giant intellectually, as well as physically, and possessed crystalline integrity. He was a good-humored, relentless and effective advocate for human rights, the environment and the Foreign Service. His efforts invariably made a difference. He was also an outstanding human being and colleague, and a true friend.

We first met in 1971, just as AFSA was gearing up to become the bargaining agent for FS employees, pursuant to President Nixon’s E. O. 11491, which established a new framework for government labor relations.

It was an exciting time. Tex had been a leading figure in the AFSA campaign along with Bill Harrop, Tom Boyatt and Hank Cohen, among others. Winning the representation election by a solid margin, they had recast AFSA. Tex later served as AFSA president and held other positions over the years, coming to epitomize the organization for many of its members.

Retirement brought no slowdown in his activism. He continued to work for AFSA, undertook speaking engagements, ran a D.C.-area foreign policy forum, continued his advocacy for human rights (most notably with Jimmy Carter), and supported the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, establishing its video program. But his true love, apart from dear Jeanie and the kids, was his computer “nest” from which he directed information (and occasional action) and internet threads on topical issues, national and international. He was tireless and irrepressible. AFSATEX1 is now silent, but he will not be forgotten.

—Jack Binns

Serving AFSA

I first met Tex in person in 2008 to talk about my running for AFSA president. We connected initially over our common love of the Foreign Service and professional diplomacy, and over the years, his love of AFSA, which I came to share. His sincerity and deep AFSA experience made him a persuasive advocate and played a role in my decision to run back then. His energetic support was key to my election.

You could count on Tex to speak his mind, even when—or especially when—he knew what he had to say would probably not be welcomed. That’s one of the reasons his participation on any team was so valuable.

Over the next decade we shared many conversations and many hours at meetings, meals and events. We became friends, allies and comrades in the context of the Foreign Service, AFSA, dissent, and later, ADST and capturing the legacy of American post–World War II diplomacy through the oral histories of its frontline practitioners. Recently, Tex partnered with ADST on his “Tales of American Diplomacy” project—one that brought together his love of new technology and of the Foreign Service. It’s a project we are determined to carry on in his honor.

Tex’s moral courage, integrity and ubiquitous advocacy for just causes, never for himself, inspire us all and earned him widespread recognition as a diplomat who made a difference in many lives. He was a true champion. He will be deeply missed and long remembered.

—Susan Johnson

The Happy Warrior

Tom Boyatt and Tex Harris pose for a snapshot while working Capitol Hill.

Courtesy of Ian Houston

In 1993, Tex Harris was elected for his first term as president of AFSA, heading the new Governing Board that took office on July 15.

AFSA / FSJ August 1993

It is very hard for me to visualize a world without Tex. For 50 years we battled together to secure an AFSA victory in union elections to represent all Foreign Service personnel; to structure an employee–management system enabling us to negotiate “personnel policies and procedures” with the foreign affairs agencies; and to establish an independent grievance system to provide for individual challenges to administrative decisions before an impartial judge.

Tex Harris was a huge (physically and operationally) presence in all of these struggles, but in achieving a grievance system enshrined in statute his heroic efforts became legendary.

This is a Foreign Service tale that needs to be retold every generation. It also serves as a metaphor for all of those qualities that made Tex the unique tribune of the people that he was.

The drive for a grievance system was sparked by an individual case. In the late 1960s Charles Thomas, a rising star in the Foreign Service, was suddenly selected out without an annuity. No one would explain to him, or later to his widow, Cynthia, how this could have happened. The total opacity of the Foreign Service rating and promotion system was fiercely defended by State management.

Distraught over his treatment and his inability to support his family, Charles Thomas took his own life. His widow, with two small children to support, was in a desperate situation. She needed a champion. Tex, in his capacity as an AFSA officer, became that champion. He was personally offended by the injustice done to Charles Thomas and his family, and equally offended by the system that enabled such treatment. He was determined to remedy the individual and institutional situations.

For seven years, beginning in 1969, Tex fought for the legislative enactment of a grievance system for the Foreign Service. As a passionate leader, he conceived how such a system would function, helped draft the details and built a coalition headed by Indiana Senator Birch Bayh (Charles Thomas was a constituent). Tex was relentless and maintained his optimism while treating his opponents without any personal malice.

Finally, in 1976 it all came together. Cynthia Thomas prevailed in her lawsuit against the State Department and herself became an FSO. The department, reacting to the sunshine on its record created by Tex and others, admitted that due to “clerical error,” the personnel folder on the wrong Charles Thomas had been sent to the Selection Board that ended Thomas’ career. The Bayh bill creating a grievance system for the Foreign Service was passed by both houses, signed by President Gerald Ford and subsequently incorporated into the Foreign Service Act of 1980 as Chapter 11.

Later in the very good year of 1976, White House Chief of Staff Don Rumsfeld arranged for President Ford to send a letter to Cynthia apologizing for what the system had done to her husband and the family, and expressing the hope that an improved system would prevent such things in the future. Charles Thomas was posthumously reinstated in the Foreign Service at the rank he previously held, and his family received the appropriate survivor annuity. (Kudos to John Naland for discovering this lovely story while researching presidential libraries.)

So let us think for a moment about how this vignette illustrates what we have lost with the passing of Tex. Gone is an implacable foe of all forms of injustice, a happy warrior who fought for his beliefs without malice toward opponents, a constant friend, a passionate Foreign Service leader who loved the Service and every member thereof, a 6’7”, 350-pound Texan who was all heart.

Our consolation is that Tex’s achievements will live on in our hearts and in the clan memories of the Foreign Service of the United States. We shall not see his like again soon.

—Thomas D. Boyatt

The End of Apartheid

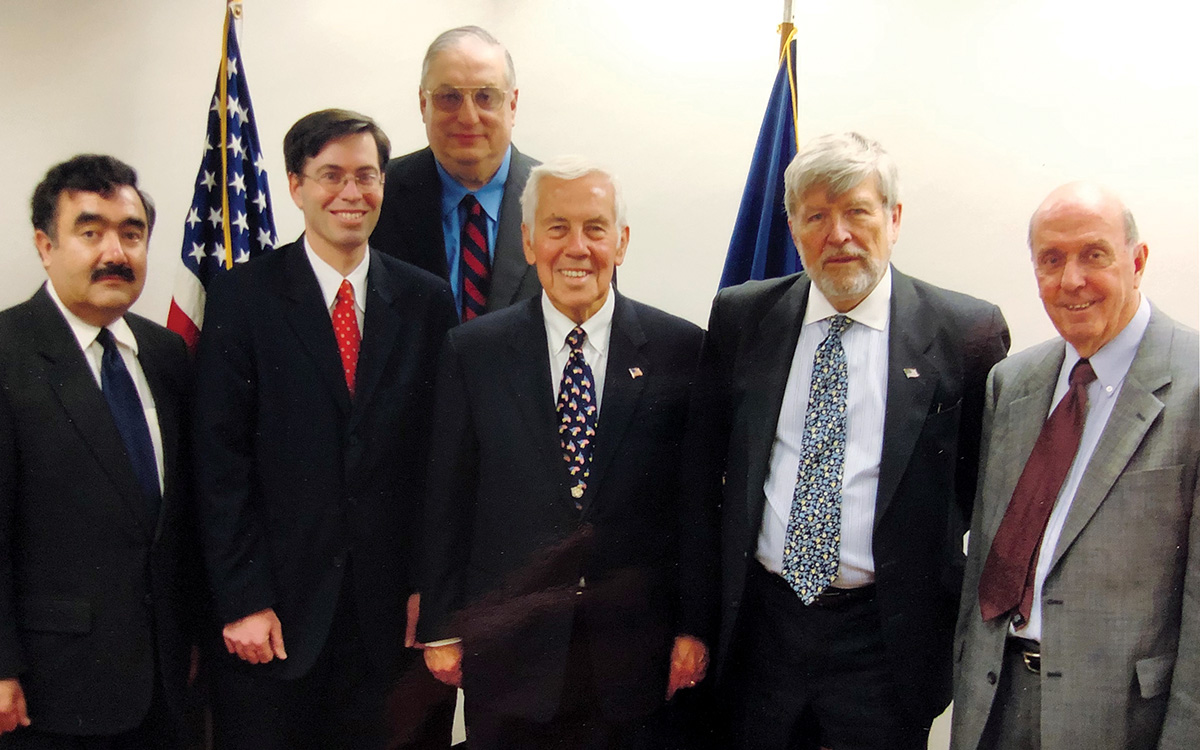

Tex Harris, back center, with Senator Richard Lugar (R-Ind.), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, following a meeting with the senator on Capitol Hill in 2007. From left: AFSA USAID VP Francisco Zamora, AFSA Executive Director Ian Houston, Harris, Lugar, and Ambassadors (ret.) Thomas Boyatt and Willard “Bill” DePree.

Courtesy of Ian Houston

Tex Harris, Tom Boyatt, Lois Roth and Hank Cohen testify at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings, March 12, 1974.

AFSA / FSJ June 1974

Tex and I first met in 1972 when I was the Congo desk officer in the Bureau of African Affairs, and he was on the board of AFSA working to make the association eligible to become the Foreign Service’s collective bargaining unit. Since I had both training and experience as a labor attaché, he asked me to organize a “Members’ Interests Committee,” which I did.

Our work was essentially to field incoming correspondence from AFSA members who requested help with problems related to working conditions abroad. As a result, we were able to help quite a few members and establish a list of areas requiring reform through eventual negotiations with management. For example, we were able to persuade management to include kindergarten in the overseas educational allowance. We also arranged for an increase in international personal effects weight allowance for secretarial and communications personnel.

Tex was vigorous in support of these improvements in working conditions in his dialogue with management.

Later, when I was senior director for Africa on the National Security Council staff (1986-1987), Tex was the U.S. consul general in Durban, South Africa. The minority-rule apartheid system was still in force, with full racial segregation and discrimination 24/7. During my visits to Durban, I saw the unique Tex Harris style that drew intellectuals from all of the races to come together at his dinner table for frank discussions. I fully believe that Tex played an important role in bringing the younger generation of white South Africans to understand that the apartheid system was doomed to fail economically, and that it had to end for the greater good of the nation.

In the whites-only election of 1989, the new president, F.W. de Klerk, made the momentous decision to begin negotiations to transition from apartheid to democratic majority rule. De Klerk told me in confidence he was planning to do this in Durban after Tex brought us together.

Our final collaboration took place from 1989 to 1993 when I was assistant secretary of State for Africa. Tex was my director for regional affairs, a job that took him into a variety of sectors. After we decided to start promoting democracy in Africa, I asked USAID/Africa if it could plan to finance relevant programs in selected African countries. The USAID office replied that it did economic development, not democracy. Tex did some investigating and found that USAID had been doing major democracy promotion projects in Latin America since the 1930s. As a result, USAID agreed to do similar projects in sub-Saharan Africa.

Tex had two qualities that made him an invaluable colleague. He was always determined to do what was right and morally justified, and he had the courage to stand up for his principles. Secondly, he never gave up. He kept pushing until he achieved the objective. And he did all that serious work while maintaining a fabulous sense of humor.

And on Saturdays, we played touch football.

—Herman J. “Hank” Cohen

Larger Than Life

F. Allen “Tex” Harris, State Department, in the 1980s.

Department of State

His many friends would say, “Tex is bigger than life,” thinking of his ebullience, good nature and unselfish consideration for others more than of his great, prepossessing physical stature. He cared deeply about people, most particularly, of course, the people of the Foreign Service, but really all people. This identification with humanity led to his now-celebrated achievements in Buenos Aires—a performance bold and career-threatening at the time, but later appreciated as a vindication of Jimmy Carter’s vision of American responsibility for global human rights. Tex was an activist for human rights throughout his life, as well as for the Foreign Service.

He was a competent lawyer and a passionate, persuasive advocate. These were significant assets as AFSA struggled to shape the executive order that would determine the relationship of the Department of State to its Foreign Service employees. Once, as chairman of AFSA, I was meeting with Under Secretary for Management Bill Macomber to hash out a critical issue. Finally, Macomber said, “OK, I’ll agree with your position—but on condition you not send Tex Harris over here again to argue with us. It is too exhausting.”

Lannon Walker, leader of the “Young Turk” reform movement that changed AFSA and the Foreign Service forever, once said of Tex: “There is not a substantive bone in that great body.” He meant that Tex was concerned with the welfare, family support, fair treatment, career ladder and effectiveness of America’s professional diplomats more than the foreign policy they conducted. That, in fact, is AFSA’s mandate, although the rest of us were more involved in policy issues aside from our AFSA responsibilities.

Tex wanted all points of view to be heard on every question. He wanted everyone to be informed and engaged, to have a say. First of all a communicator, he maintained an active email listserv with scores of recipients. Once in a while his admirable support of comprehensive democracy could prove awkward for negotiations or decision-making, and his colleagues on the AFSA Governing Board would worry about including Tex in the gestation of a sensitive issue not yet ripe for general debate. Anything Tex knew was soon available to the world.

The most loyal, patient and thoughtful friend imaginable throughout his too-short life, optimistic, considerate, warm-hearted. If you were interested in gossip or bad-mouthing of others, of anyone, Tex was not your man.

I loved Tex Harris and am not reconciled to losing him.

—William Harrop

A Constant Inspiring Presence

Tex was a Foreign Service guardian. Ever-present, he was AFSA, and AFSA was Tex. I remember well sitting in the tiny closet of a classified reading room at Embassy Bishkek in 1993, reading cables and finding the missives from AFSA President Tex Harris to be most enjoyable. I don’t remember what he said, but his messages made me feel like I was part of something bigger than myself, bigger than my post.

Later, throughout my time with The Foreign Service Journal, Tex was there too, as a cheerleader for the Service and for the Journal, always concerned about some new injustice and always advocating for the members of the Foreign Service. He appreciated and valued the magazine in a way few others have. I am forever grateful for his support and understanding.

When I last spoke with him, in the middle of the October 2019 reception after he’d received AFSA’s Award for Achievement and Contributions to the Association, we had a great talk about the Speaking Out column he was going to write on climate change for an upcoming issue of the Journal. Although he won’t be writing that article, the spirit of his commitment to making the world a better and more equitable place will live on in the Journal, in AFSA and all who knew him.

—Shawn Dorman

Onward

During his second term as AFSA president, in August 1996, Tex Harris (at left) led a demonstration outside USAID Administrator Brian Atwood’s office to demand “better management” at the agency, where reductions-in-force (RIFs) were decimating Foreign Service ranks. AFSA USAID VP Frank Miller is at right.

AFSA / FSJ September 1996

Tex sent me at least 1,000 emails over the 21 years since I first joined the AFSA Governing Board. The last was sent at 9:16 a.m. on the day of his sudden illness and death. Typically, it was not an action request for me, but rather an information copy about a Foreign Service issue that he wanted others to be aware of. That was vintage Tex. He was always working to share information and bring people together toward a common goal.

As the first two-term AFSA president (1993-1997), Tex sent almost weekly reports to the field via State Department telegram to keep members informed about AFSA’s advocacy on their behalf. His messages often revealed some ill-conceived personnel policy being considered by State or USAID. If agency management persisted in pursuing that policy, they could be assured of reading about it a few days later in the Washington Post’s “In the Loop” government gossip column. Everyone knew where the Post got that information.

I was honored to serve with Tex on several AFSA Governing Boards. He cared deeply about diplomacy and the career Foreign Service. It is fitting that the last words of his last email to me were “Onward, Tex.”

—John Naland

Joining the Bray Board

I was shocked to hear that Tex Harris died less than two weeks after enjoying an email exchange with him that called up memories of our work together in 1970, when I recruited him to an open spot on Charlie Bray’s AFSA Governing Board so that he could help us win the Foreign Service vote turning AFSA into a union to protect our rights.

Tex went to work wholeheartedly, a firm support for AFSA over all this time, including his presidency. Although we had been out of touch for years, we picked up a couple of weeks ago, before I wrote this remembrance, where we had left off. I recalled his characteristic gushing warmth as he described his continuing contact and friendship with our mutual AFSA friends. We discovered that we were both alumni of Princeton, and he said he would meet me there at the 70th reunion of my class in 2022. Although he has gone, his memory will long be cherished.

—George Lambrakis

Australia Days

Tex and his wife, Jeanie, in 1982 in Washington, D.C.

CEDOC

I was a second-tour officer when Tex Harris arrived in Melbourne as our new consul general. “I’m an ideas guy,” he told us. “Most of my ideas will be bad but a few will be good, and it’s your job to tell me the difference.”

I took him up on his offer and was tasked straightaway with raising our public diplomacy game. Tex was fond of U.S. Navy ship visits—we put Australia’s top leaders on aircraft carriers and American sailors to work on neighborhood projects.

His enthusiasm was infectious. I remember writing a cable on Australia’s rural-urban divide; it was probably noticed by one bored desk officer and an analyst or two in INR, but Tex heaped so much praise on it I felt like George Kennan. When I screwed up, he didn’t hesitate to tell me that either, and I was always better for it.

In a way, Tex was too big for little Melbourne—too big for anywhere maybe—but the Australians couldn’t get enough of him. And neither, I think, could the rest of the world. Everything about Tex was big—his handshake, his laugh, his ideas and his heart. He was the opposite of typical, as American as they come, and truly one of a kind.

—Jim DeHart

Remembering Tex in South America

Memories about Tex Harris surfaced often during a cruise I just completed around South America.

There was the square in Buenos Aires where women still commemorate each Thursday those family members who disappeared under the Argentine junta. Fearlessly, Tex took the physical and bureaucratic risks needed to expose these atrocities.

In Lima, memories of Tex were heightened with the news that former U.N. Secretary General Pérez de Cuéllar had died. To cope with war and famine in Africa’s Greater Horn, 1984-85, State Refugee Bureau leadership intervened with de Cuéllar to launch the U.N. Organization for Emergency Operations in Africa, described later as “The U.N.’s Finest Hour.” But it took Tex Harris, head of the bureau’s emergency unit, tirelessly mentoring and facilitating from alongside the U.N. field effort, to enable it to clinch that extraordinary title.

That was vintage Tex, bigger than life, typically in the toughest humanitarian arenas, and forever now in our hearts.

—Arthur E. “Gene” Dewey

Outsized Loss

What a loss!

Everything about Tex was outsized. His energy and enthusiasm; his outlook and optimism; his spirit and voice; his vision and influence; his interests and engagement; his height and girth; and his heart (hard to believe that gave out); even his walker was Texas-sized. And his passing means that the hole in all of our lives will be equally outsized.

—Thomas “Ted” E. McNamara

Help Honor Tex Harris

Please help AFSA perpetuate one of the signature legacies of this giant of our profession by donating to permanently endow the Tex Harris Award for Constructive Dissent by a Foreign Service Specialist.

Tex championed the creation of this award in 1999 at a time when AFSA dissent awards honored only Foreign Service officers. Since then, 14 specialists have been recognized. Funding for the $4,000 cash award is currently taken from the general AFSA budget; but in memory of Tex, AFSA seeks to raise funds to permanently endow the award.

With a generous seed donation of $10,000 from the Nelson B. Delavan Foundation, thanks to Ambassador (ret.) William Harrop and Mrs. Ann Delavan Harrop, AFSA hopes to raise an additional $50,000 so that this important award can be funded in perpetuity. Toward that goal, the Foreign Affairs Retirees of Northern Virginia have pledged $1,000 and the Foreign Affairs Retirees of Maryland and Washington, D.C., pledged $500.

We hope AFSA members and retiree groups will join us to support a fitting living memorial to our friend Tex.

To donate, please go to www.afsa.org/donate or send a check (“Tex Harris Award” on memo line) to AFSA, c/o Tex Harris Award, 2101 E Street NW, Washington DC 20037.