Why Nuclear Arms Control Matters Today

In this time of new strains in great-power relations, nuclear arms control agreements are an essential component of national security.

BY THOMAS COUNTRYMAN

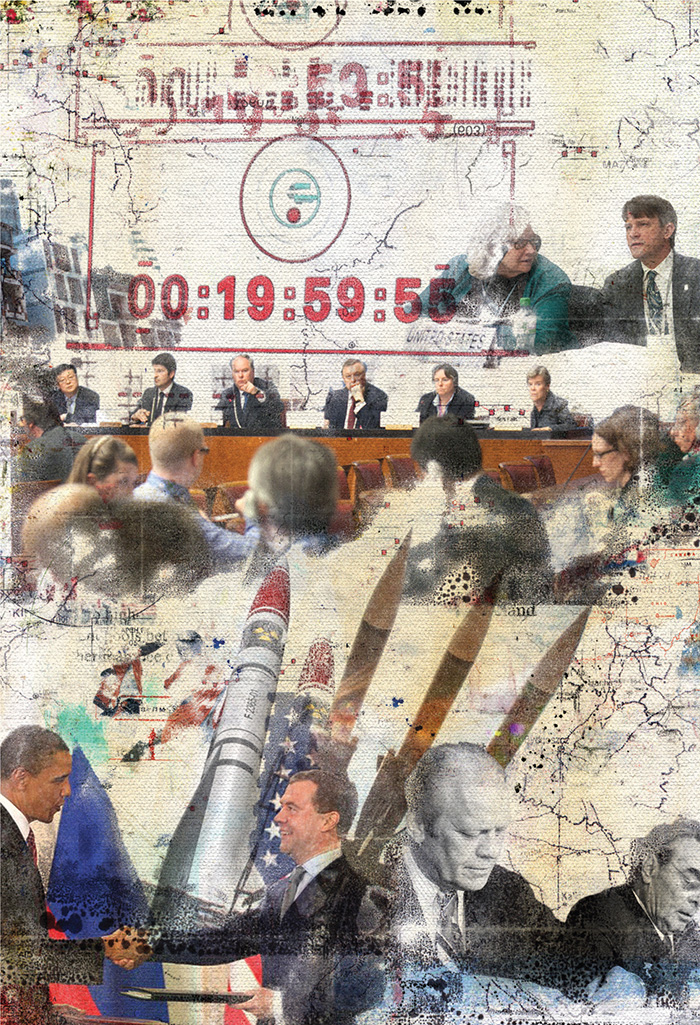

Brian Hubble

Before 2017, every U.S. president dating back to John F. Kennedy proposed and pursued negotiations with Moscow as a means to regulate destabilizing nuclear arms competition and reduce the risk of the United States and its allies being destroyed in a nuclear war. With their diplomatic and military advisers, they sought and concluded a series of treaties, most with strong bipartisan support, that have made the United States and the world much safer, and reduced U.S. and Russian arsenals by 85 percent from Cold War peaks.

The current administration, however, is veering off course from the approach to nuclear risk reduction and arms control pursued by previous Republican and Democratic administrations. Worse, President Donald Trump’s team has not presented a coherent alternative road map to reduce the threats posed by nuclear weapons.

This departure from proven and effective nuclear risk reduction and arms control strategies is a matter of urgent concern, because, among other things, we face a higher risk of a U.S.-Russian nuclear war than at any time since the end of the Cold War.

Proven Rules of the Road

Previous U.S. presidents understood that talking to an adversary is not a sign of weakness, but a hardheaded and realistic means to reduce an existential threat posed to the United States. They came to realize that well-crafted arms control and nonproliferation treaties provide rules of the road that enable the United States to more effectively pursue its economic and security interests.

As Thomas Schelling and Morton Halperin argued in their seminal 1961 study, Strategy and Arms Control, nuclear weapons limitation agreements with adversaries can help achieve three critical foreign policy objectives: “the avoidance of war that neither side wants, minimizing the costs and risks of the arms competition, and curtailing the scope and violence of war in the event it occurs.”

Throughout the nuclear age, U.S. policymakers—from William Foster, Henry Kissinger, George Shultz and Brent Scowcroft to John Kerry and Rose Gottemoeller—have pursued arms control agreements because they are a vital tool that can constrain other nations’ ability to act against our interests, while still allowing the freedom of action that is necessary to defend U.S. interests and those of our close allies. In other words, arms control agreements are not a concession made by the United States, nor a favor done for another nation; they are an essential component of, and contributor to, our national security.

The United States today has no proposals on the table for new agreements that would reduce the risk of nuclear war, other than a vague and passive call for trilateral negotiations with Beijing and Moscow.

The history of the nuclear age also shows that the United States, as the world’s first and most sophisticated nuclear weapons power, must play an active role as a global leader on nuclear security matters, both bilaterally and multilaterally. Negotiating to end the arms race, achieve reductions of nuclear stockpiles and, eventually, eliminate all nuclear weapons is not only a moral obligation, but a legal obligation under Article VI of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons since its approval by the U.S. Senate in 1969. These goals can and must be pursued, regardless of the ups and downs of great-power relations.

Most U.S. presidents have come to recognize that the pursuit of these goals is not an option, but a priority. Mutual assured destruction is not a theory or a philosophy; it is a reality. Once the Soviet Union achieved reliable intercontinental ballistic missiles in the 1960s, neither the United States nor Russia could launch a nuclear attack on the other’s homeland without the near-certain destruction of its own homeland.

New Road, No Rules

In a departure from this history, the Trump administration has abandoned U.S. leadership in the arms control field and seems guided by a contrary set of assertions that have gained salience on the hawkish side of the Republican party, namely:

• The United States should not discuss vital national security issues, or consider compromise, with adversaries such as Iran until they have fully met U.S. demands in all fields.

• Arms control agreements grant unwarranted concessions to opponents, and they constrain the United States’ freedom of action. (This has been the guiding principle for John Bolton, former national security adviser and a serial assassin of arms control agreements.)

• Arms control agreements serve little value if they do not solve every problem between the parties. This all-or-nothing approach is exemplified by the U.S. decision to withdraw from the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

• We must be prepared and willing to wage, and prevail in, a “limited” nuclear war, which can remain “limited.” This mirrors an increased Russian interest in the same topic and is exemplified in the renewed U.S. program for construction of nonstrategic (so-called “low-yield”) warheads and delivery systems.

• The United States can achieve a numerical or technical advantage over our nuclear-armed adversaries by constantly pursuing improvements and new nuclear weapons capabilities. (The administration’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review makes several references to the U.S. “technical edge,” which is of little relevance in an all-out nuclear conflict.)

In both Moscow and Washington, military and strategic thinkers are again talking about the plausibility of “limited nuclear war.”

Sadly, no U.S. official today is allowed to repeat the obvious fact that motivated President Ronald Reagan and General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev to jointly declare in November 1985: “A nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought.” (The White House is reportedly concerned that repeating this declaration would send the wrong message to Pyongyang.)

Ignoring Core Arguments

In a Feb. 11 speech in London originally titled “The Psychopolitics of Arms Control,” Assistant Secretary of State for International Security and Nonproliferation Chris Ford laid out the administration’s critique of arms control advocates. In seeking to take down several straw-man arguments, which he termed the “pathologies” of those who advocate for “outdated” approaches to arms control, Ford attributed to unnamed advocates words they never said, while ignoring their core arguments. He falsely accused arms control practitioners, presumably going back through the decades, of being unconcerned about national and international security and of using support for arms reduction as “absolutist performative moralism,” “ideological identity politics” and a means of “virtue signaling.”

Such accusations do great disservice to the many dedicated national security professionals who work in this field, both inside and outside government. There is a genuine disagreement whether, as Ford argued in the same speech, a favorable international security environment is a precondition for disarmament or, instead (as I believe history demonstrates), disarmament helps to foster international security. But Ford is wrong to say that those who may be critical of this administration’s approach on nuclear weapons policy matters are blind to the actual security conditions that shape our foreign policy and arms control goals.

Ford also erroneously charged that the arms control community ignored Russia’s violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty and suggested there should be no response other than the United States remaining in the INF Treaty. There were alternatives to the United States leaving the treaty and options for bringing Russia back into compliance, none of which were perfect. But the United States’ exit from INF, even if justified by Russia’s violation, was not the only possible course of action, nor even a smart thing to do.

Ford may be right, as he argued in his speech, that the credibility of agreements requires a readiness to abandon agreements that are being violated. But that does not explain the Trump administration’s violation of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Program of Action, with which Iran was in compliance, or its reluctance to extend the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which both Russia and the United States are implementing in full, but which is due to expire in less than a year unless extended by mutual agreement.

A Dangerous Void

Ford’s claim that the United States is pursuing new forms of arms control has the same credibility as most White House pronouncements these days. What is most embarrassing for those of us who took pride in seven decades of America’s global leadership in arms control, always setting the global security and risk reduction agenda, is that the United States today has no proposals on the table for new agreements that would reduce the risk of nuclear war, other than a vague and passive call for trilateral negotiations with Beijing and Moscow on nuclear arms control. Worse, a year after floating the idea, the administration has not even bothered to sketch out any possible incentive for China (whose nuclear arsenal is one-twentieth the size of the Russian and U.S. arsenals) to join in such a negotiation.

At the same time, President Trump implausibly pledges to make the United States “invulnerable to missile attack,” and his officials have refused to engage in negotiations on the topic of ballistic missile defense, the U.S. program that stokes Russian paranoia and that Vladimir Putin uses to justify his own pursuit of new and more dangerous weapons systems.

In both Moscow and Washington, military and strategic thinkers are again talking about the plausibility of “limited nuclear war” and are building the delivery systems and warheads that make first use of nuclear weapons (by either side) more credible and thus more likely. There are more potential flash points between NATO and Russian forces in Europe—and more provocative Russian behavior—that could cause an accident to escalate into an incident that becomes a conventional war that escalates to a nuclear war.

In an environment of aggressive cyber warfare by powers large and small, there is also a higher risk of a false alarm triggering a nuclear response, an outcome we escaped with minutes to spare at several points during the Cold War. And in surveying the personality and politics of the nine men who have their fingers on nuclear buttons, there is good reason to be concerned that any of them might put their personal ambitions ahead of the planet’s security.

So what do we do?

Urgent Tasks

The most urgent task is renewal of the New START agreement before it expires on Feb. 5, 2021. This does not require a return to the treaty graveyard of the U.S. Senate, but only the signature of two presidents, which Putin has declared he is ready for without conditions. If no action is taken, we will have no numerical limits on U.S. and Russian deployed nuclear weapons for the first time in 50 years. We will also lose the notification and inspection provisions that give us insight into Russia’s nuclear capabilities.

And we will touch off—gradually at first, and then rapidly—an open-ended nuclear arms race that will exceed in risk and expense what we experienced during the Cold War. It would be a race without winners, and unaffordable, as it would greatly increase the $1.7 trillion already scheduled to be spent on rebuilding and expanding the U.S. nuclear arsenal over the next 30 years. (By the way, the president’s budget proposal for Fiscal Year 2021 allocates more money to the nuclear weapons enterprise than to the entire diplomacy and development budget.)

In the longer term, it is important to rebuild the capacity of our diplomatic and military community to deal with these issues in a hardheaded way.

In an election year, it is to be hoped that the president will recognize that there is no other foreign policy step he can take (particularly regarding Russia) that would be welcomed by both Democrats and Republicans as much as an extension of New START. This could also kick-start a more intensive U.S.-Russian strategic stability dialogue, one that thoroughly explores the legitimate security concerns of both sides, with no topics excluded. (The three sessions of this dialogue held since 2017 have been brief, desultory encounters and have apparently not even agreed on an agenda for future work.) A New START extension would do far more than the administration’s current rhetoric in making it possible to advance the praiseworthy goals the president has advocated but done nothing to move forward: addressing both new strategic weapons and nonstrategic nuclear weapons, and bringing China more fully into the nuclear risk reduction process.

Beyond that, the Department of State has initiated a multicountry dialogue on “Creating the Environment for Nuclear Disarmament” (CEND). This is a dialogue worth having, even if it is only a less-formal talk shop than the Geneva-based U.N. Conference on Disarmament, which is an organization that makes your local Department of Motor Vehicles office seem dynamic. But the United States also has to address the skepticism of most CEND participants that this is intended as a means to lessen international pressure for progress on nuclear arms control action while the United States modernizes and expands its nuclear arsenal. Washington must also be willing to listen to its allies, who unanimously support New START extension, and most of whom believe it is possible to respond to the demise of the INF Treaty by means other than reprising the Euromissile crisis of the 1980s.

In the longer term, it is important to rebuild the capacity of our diplomatic and military community to deal with these issues in a hardheaded way. With no genuine arms control negotiations for nearly 10 years, since conclusion of the New START treaty in 2010, we have few experts who have actually dealt with the Russians, particularly in the deliberately emaciated Department of State. Beyond the next round of negotiations, it is important that the U.S. educational system (with the support of the government) produce a new generation of experts in nuclear, Russian and Chinese affairs.

Discarding a 60-year history of agreements that have improved America’s national security, saved us trillions of dollars, made it possible to invest in more effective means of defense and reduced a literally existential risk to the human race is a dangerous act of deliberate ideological blindness. In the current environment of great-power competition, there will have to be new approaches to arms control. They will not be found by rebranding “re-armament” as “arms control.”