The Paris Accord: An Experiment in Polylateralism

The structure of the 2015 accord is unique, and may be a decisive factor in its effectiveness in combating climate change.

BY THERESA SABONIS-HELF

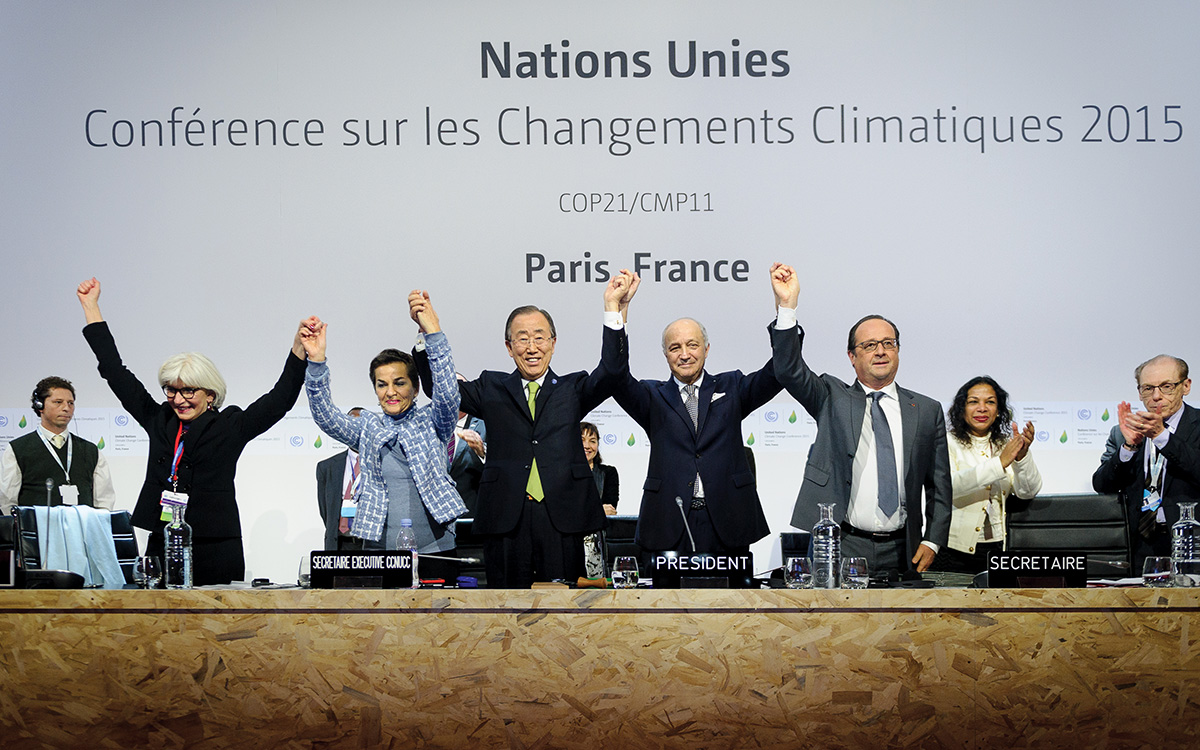

Celebrating adoption of the Paris Agreement at the United Nations Climate Change Conference of Parties 21 of Dec. 12, 2015, in Paris. From right to left: French President Francois Hollande, French Foreign Minister and President of COP 21 Laurent Fabius, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon and Executive Secretary of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change Christiana Figueres.

Arnaud Bouissou

Although the impact of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement on the progress of combating climate change is rightly the focus of most analysis, and remains to be seen, the structure of the treaty is noteworthy in that it reflects the likely future of treaty-making in a posthegemonic world. The treaty is founded on the diplomatic pillar of a bottom-up approach; the legal pillar of combining hard law (on mandatory transparency) and soft law (on enforcement via naming-and-shaming); and the economic pillar of engaging corporate strategies and consumer preferences, as authors Rafael Leal-Arcas and Antonio Morelli have observed (see Resources, below).

Such an approach to multilateralism offers an answer to the question of how to shape internationally important behavior in a world in which power is increasingly dispersed, both among and within states. It resolves key failures in previous attempts at climate treaties. It also serves as a landmark of “polylateralism,” the practice of creating new roles for nonstate actors in the implementation of a treaty among sovereigns.

The Paris Accord and Its Predecessors

The U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change was signed in 1992 and adopted in 1994. The UNFCCC Treaty, of which the United States has been a member since ratification, defines the problem of climate change. This treaty established reporting mechanisms, expert panels to review and advance understanding of climate change (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC) and a responsibility to meet regularly in Conferences of the Parties (COPs) to establish mechanisms to contain climate change.

The first major attempt to bring the treaty to life was at COP 3, which took place in 1997 and produced the Kyoto Protocol. It eventually failed in its effort to create an international architecture for controlling emissions. Although President Bill Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol in December 1997, he never submitted it to a skeptical Congress, and President George W. Bush acted rapidly after his inauguration to withdraw the U.S. signature.

Critics of the Kyoto Protocol faulted the nontransparent way in which targets for developed countries (Annex I signatories) had been negotiated, the lack of obligations on the part of the developing world (Annex II signatories) and the complex “flexible mechanisms” that proved difficult to monitor and measure. When Russia became the final signatory needed to bring the agreement into force in February 2005, critics noted that it had ridden a tide of anti-Americanism. Although flawed and without the United States, the protocol was extended past its 2012 expiration, while COPs struggled toward next steps.

The accord has been described as simultaneously legally binding and voluntary—a balance of hard and soft law.

Kyoto’s eventual replacement was the Paris Agreement, adopted at COP 21 in 2015, which is structured very differently. It expresses the overall goal of keeping the global temperature rise at less than 2 degrees Celsius (ideally 1.5 degrees Celsius) above preindustrial levels. Instead of identifying targets to be met by member nations, the treaty leaves this decision to the nations themselves. Member states are required to submit Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) every five years, and commit to increasing the ambition of their goals over time.

INDCs are made available in a public registry maintained by the UNFCCC Secretariat. The commitments made, as well as the success of implementation, are subject to publicly available peer review. A periodic synthesis report shows whether the pledges made are sufficient to achieve the Paris Agreement goal. No punishment is specified for states that fail to implement their INDCs. The accord has been described as simultaneously legally binding and voluntary—a balance of hard and soft law.

The level of autonomy accorded to states was important to U.S. negotiators. Hoping to avoid the challenge faced by the Clinton administration, U.S. negotiators had worked to shape the accord so that it would not necessarily require Senate ratification. The Obama administration argued that all the legally binding aspects of the agreement (largely reporting requirements) were already covered by the founding UNFCCC treaty, while the INDCs were self-designed and nonbinding.

Breaking a Climate of Deadlock

Although it remains to be seen if the Paris Agreement can effectively reduce emissions, it is nonetheless regarded as a rare success among climate negotiations in sustaining engagement of the parties. Climate negotiations have traditionally been fraught. Deadlock-producing disputes turn on complex technical issues, stark equity issues and problems with uncertainty. For example, upper atmosphere pollutants such as greenhouse gases (GHGs) can persist for centuries, so simply reducing emissions proves insufficient to repair the damage already done. This creates a dispute about how to compare the “differentiated responsibilities” of a traditional polluter, such as the United States, which currently produces about 15 percent of daily global emissions (but has been emitting for centuries) to those of China, which is a relative newcomer to high GHG levels but is currently producing 30 percent of daily global emissions.

This challenge is compounded by the centrality of fossil fuels to industrialization. Industrializing countries are eager to catch up economically, and they lack confidence that it is possible to “rise” without emissions rising as well. There is fear that lack of access to funding for electricity development will condemn poor countries to darkness. The centrality of energy to the global economy is troubling for all states: The IPCC estimates that 55 percent of global GHG emissions are directly connected to energy use, so how to maintain—much less expand—standards of living in a GHG-constrained environment is a grave concern.

An even broader equity issue bedeviled the negotiations of every COP: The very fact that 197 countries had signed the UNFCCC meant that all would be included in the negotiations, even though the volume of emissions, the effect of climate change and the capacity of states varied dramatically among countries. Negotiations involving more than 190 countries on a scientifically complex, economically challenging issue led to prioritization problems: OPEC nations, for example, wanted to ensure that they would be assisted if a transition away from fossil fuels dramatically reduced their national wealth. Nations with skeptical populations wanted more research to prove origins of the problem. Agricultural nations wanted to ensure that they received appropriate credit for carbon-sequestering crops. Small island nations sought assurances that their populations would be accepted as refugees if their homelands became uninhabitable. In short, the issues were so many and varied that even good-faith negotiators could not agree on priorities.

By connecting investors, state and local government, industry and activists, the Paris Agreement attempts to engender the innovation required to pursue its transformative goals.

Annex II (developing) countries had no obligation to reduce emissions under the early treaties. The Group of 77, fearful that pressure might grow in the future on developing countries to curb emissions and thereby potentially limit their own growth, compelled removal from the Kyoto Protocol of an article that detailed how a non-Annex I country might take on a voluntary commitment. (Argentina attempted to take on a commitment but was unable to do so; and Kazakhstan, which tried to gain membership in Annex I, struggled from COP 4 to COP 7 to achieve that laudable goal.)

Eager to find a way to move forward, the Obama administration concluded that, although meetings involving all the parties were essential, setting the table bilaterally would increase the prospects for success. Since China and the United States were the top emitters, the administration sought bilateral agreement. China, although it had long considered climate change a developed world problem, had begun to shift its narrative in 2009, when it promised at the COP 15 to reduce the energy intensity of its economy and expand the use of nonfossil fuels. According to scholar Miranda Schreurs, this shift likely reflected China’s struggles with air quality, its dramatic increase in energy imports and its rising per-capita energy consumption.

Xi Jinping proved a willing partner with Obama, and in November 2014 they released a “U.S.-China Joint Announcement on Climate Change and Energy Cooperation.” The announcement explicitly embraced the idea of INDCs and sketched out what would be included in the U.S. and the China plans. The promised actions were criticized for their modest ambition, but the model of stating intended contributions was brought to Paris with the full endorsement of the top two emitters, paving the way for a breakthrough.

This effort was further amplified by the European Union. Long a supporter of binding international commitments, the E.U. announced its ambitious new 2030 emissions reduction target just prior to the 2014 U.S.-China summit. Attempting to set an example, the E.U. announced ambitious targets of 40 percent GHG reductions by 2030, combined with a 27 percent increase in renewable energy and a 27 percent increase in energy efficiency of GDP. Their specification of a target together with renewable and efficiency contributions were mirrored in China’s announcement. Since China, the United States and the European Union constitute the top emitters (accounting for 54 percent of global emissions according to the Environmental Protection Agency), a climate strategy supported by these three solidified Paris’ new direction.

Polylateralism: Enter the Nonstate Actors

Resources

Global Climate Action NAZCA Registry

Rafael Leal-Arcas and Antonio Morelli, “The Resilience of the Paris Agreement: Negotiating and Implementing the Climate Regime,” Georgetown Environmental Law Review, 2018, Vol. 31, Issue 1

Miranda A. Schreurs, “The Paris Climate Agreement and the Three Largest Emitters: China, the United States, and the European Union,” Politics and Governance, 2016, Vol. 4, Issue 3

U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat, “Nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement: Synthesis report by the secretariat,” Feb. 26, 2021

United Nations, “Paris Agreement,” 2015, English text

The 2015 Paris negotiations, like all the COPs before them, attracted participation from interested nonstate actors. The Paris Agreement structure, however, was the first to create an explicit role for them. The treaty was signed and ratified by sovereign states, but Article 6.4 calls for signatories to encourage public and private entities. Nonstate actors have no obligation under the treaty to report to the UNFCCC, but they may make use of the “Non-state Actor Zone for Climate Actions” registry, posting their own intended commitments for review and critique. The NAZCA registry currently boasts 19,690 “actors,” of which 2,148 are American—including 16 states, 246 cities, 832 companies and 854 organizations, each of which has committed to specific GHG reduction strategies and targets.

The promotion and mutual review of targets, policies and strategies has enabled nonstate actors to organize in new ways. Although COP 23 (2017) occurred after the United States had begun the process of withdrawing from the treaty, a U.S. team under the banner of “We Are Still In” attended the conference representing 20 states, 110 U.S. cities and more than 1,400 businesses. This group also began releasing an annual report, “America’s Pledge,” which quantified the impact of U.S. nonfederal actors working toward the Paris accord goals. “We Are Still In” continued to attend subsequent COPs, growing in size. As the Biden administration returned the U.S. to the Paris accord, the group renamed itself “America Is All In” and helped shape (and then endorsed) the April 2021 new U.S. INDC commitment to reduce emissions by 50-52 percent (from 2005 levels) by 2030.

This movement highlighted what the drafters of the Paris Agreement had intended to be an important aspect of the treaty. With no sanctions identified, the accord relies on the “soft law” approach of “naming and shaming” signatories who either adopt modest goals in their INDCs or fail to achieve the results promised. It was hoped that mobilizing “nonparty stakeholders” from civil society, state and local government, and industry could help lead governments toward more ambitious goals while simultaneously demonstrating how to implement change.

Another example of nonparty stakeholder leadership comes from two organizations closely associated with the Paris conference: Mission Innovation and the Breakthrough Energy Coalition. The former is an intergovernmental and public-private platform that involves 23 U.S. states and seeks to connect global research and development to accelerate clean energy innovation. The latter is a multibillion-dollar venture capital program, led by notables in the U.S. high-tech sector, which seeks to provide flexible early-stage investment for promising technologies in next-generation energy development. Both organizations support the Paris accord, and both explain their work in terms of accelerating progress toward its goals.

By connecting investors, state and local government, industry and activists, the Paris Agreement attempts to engender the innovation required to pursue its transformative goals. Organizing states and nonstate actors toward cooperative problem-solving is an approach the United Nations used to good effect in the Millennium Development Goals. Implementation of this kind of hybrid multilateralism in a treaty focused on climate change is simultaneously a recognition of the limits of state power in addressing the issue and an effort to embrace the dynamism of nonstate actors who may pursue solutions with more creativity.

Read More...

- “It’s Not Just about Paris: International Climate Action Today,” by Karen and Ann Florini, The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2017

- “The Climate Crisis: Working Together for Future Generations,” by U.S. Department of State

- “IPCC report: ‘Code red’ for human driven global heating, warns UN chief,” by United Nations, August 9, 2021