USAID at 60: An Enduring Purpose, a Complex Legacy

Here is an anniversary review of the agency's founding and evolution, as well as its shortcomings and accomplishments.

BY JOHN NORRIS

USAID staff welcome another shipment of U.S.-donated COVID-19 vaccine deliveries to Uganda in the summer of 2021.

USAID

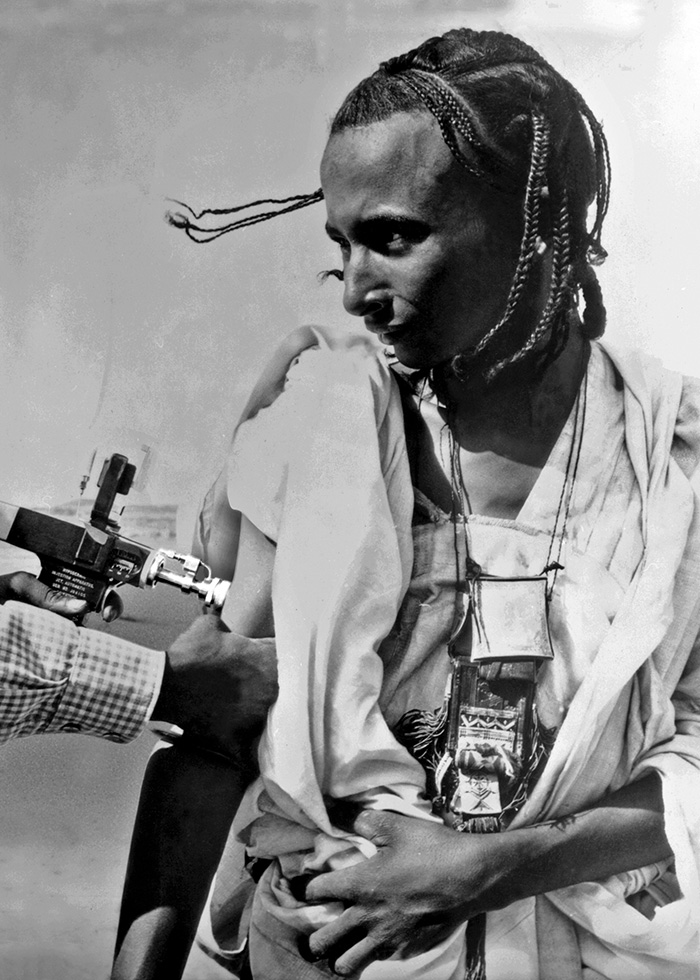

A Nigerien man receives a vaccination by way of a Ped-O-Jet jet injector. This image was captured in Niger in 1969, during the worldwide Smallpox Eradication and Measles Control Program.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

As the U.S. Agency for International Development, USAID, marks its 60th anniversary this month, the moment is ripe to reflect on both its accomplishments and shortcomings. Working in well more than 100 countries during this period, both sides of the ledger are striking.

USAID and its many partners in development have helped achieve what by any reasonable accounting must be considered unprecedented advances in the human condition since the agency’s founding. Smallpox—in an unusual collaboration between USAID, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization and the Soviet Union—was eradicated after an innovative vaccination campaign. This was the first time a disease had ever been eradicated on a global basis; that fact was made still more impressive given that smallpox killed more than 300 million people worldwide in the 20th century alone.

USAID spearheaded child survival campaigns with its partners, saving millions of lives with a simple intervention of oral rehydration therapy that costs only pennies per packet to produce. The Green Revolution, championed by the Johnson administration and advanced through research funded by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, staved off what many feared would be an era of global famine while boosting incomes for poor farmers. Countries such as Taiwan and South Korea, once dismissed as economic backwaters, were transformed into economic powerhouses (and, ultimately, donors themselves), in no small part because of large U.S. investments through USAID, particularly in building the technocratic expertise within their planning and finance ministries.

But for the critics of foreign aid, of whom there has always been a seemingly inexhaustible supply, USAID’s shortcomings have at times been glaring. From the fall of Vietnam to recent events in Afghanistan, some of the agency’s largest and most expensive programs collapsed upon themselves with shifting political and military tides. Over the years, money has flowed to dictatorial regimes, first because of their Cold War bona fides, and later to sway erstwhile allies in the global war on terror. Perhaps no federal agency has been scrutinized more closely by Congress or a longer series of blue-ribbon panels eager to surface meaningful reforms.

USAID’s legacy is complex, deserving of neither hagiography nor damnation as is too often the case. And the world in which the agency operates has been almost utterly transformed over those six decades. But the raison d’être for USAID and its work remains surprisingly constant. As William Gaud, one of the agency’s early leaders, argued, there are two basic reasons for the United States to provide foreign assistance: It is in our self-interest, and it is the right thing to do.

So let us look back to the agency’s founding to better understand some of the debates that continue to follow the agency to this day and then explore how the agency has evolved over time.

Kennedy’s Vision

On June 8, 1962, President John F. Kennedy delivers remarks at the White House to a group of USAID mission directors shortly after the agency was established. “There will not be farewell parades to you as you leave or parades when you come back,” he told them.

Robert Knudsen / JFK Presidential Library and Museum

To better understand USAID, it is helpful to understand the worldview of the man who created it: President John F. Kennedy. As a young congressman, Kennedy was not a supporter of U.S. foreign assistance. However, his views on the developing world began to change rather drastically during a seven-week, 25,000-mile congressional trip in 1951, when he traveled to Israel, Pakistan, India, Malaysia, Thailand, Korea, Japan—and what was known then as French Indochina, and later as Vietnam. He came away with a newfound affinity for those in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America fighting to establish their own nation and identity. He argued that communism could not be combated solely through the force of arms and pushed for expanding economic aid. His support for independence movements was frequently cited at the time as an example of his lack of maturity on foreign policy, although those views seem far sounder in retrospect.

Kennedy’s views of foreign aid were also shaped to a remarkable degree by a piece of fiction: the 1958 novel The Ugly American by William J. Lederer and Eugene Burdick. The book detailed the bumbling exploits of Americans in a fictional Asian country, outflanked at every turn by shrewd communists, and scorched its way up the bestseller list, where it remained for a 76-week run. Kennedy, who had become a senator in 1953, was so enthusiastic about the book that he not only purchased copies for all his Senate colleagues; he also took out a full-page ad in The New York Times praising its depiction of Americans working overseas.

It was not just The Ugly American that raised concerns about foreign aid. No fewer than six different major studies of the U.S. aid program were conducted during the late 1950s, many of them highly critical. Responsibilities for the program were diffuse, scattered across multiple competing agencies that operated under overlapping and sometimes contradictory mandates. Public support for aid was waning, and the U.S. government was beginning to realize that implementing foreign assistance programs in the developing world—the new front line against communism—was much more difficult than implied by the triumphs of the Marshall Plan. The early optimism was exemplified by Henry Bennett, who oversaw much of the aid program during the early 1950s and boldly predicted that hunger, poverty and ignorance would end around the globe for all practical purposes within 50 years.

With Cuba falling to Fidel Castro on New Year’s Day 1959, the debate about America’s relationship with the developing world reached a crescendo. There was no real practical theory on how best to help the largely subsistence agrarian societies of Asia, Latin America and Africa make the leap into modernity. “The gap between the developed and underdeveloped worlds,” Kennedy argued, was a “challenge to which we have responded most sporadically, most timidly, and most inadequately.”

Once elected, Kennedy quickly turned to plans to overhaul the foreign assistance program. In his first meeting with the National Security Council in 1961, he directed the Bureau of the Budget to develop recommendations on foreign aid, and this effort was combined with the work of a task force already developing recommendations for the president that included Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs George Ball, Budget Director David Bell and Henry Labouisse (who was in charge of much of the existing aid program at the time).

Kennedy was also deeply influenced by the thinking of two MIT academics who were making a splash with new theories on foreign assistance: Walt Rostow and Max Millikan. Their prime recommendation: “The United States should launch at the earliest possible moment a long-term program for sustained economic growth in the free world.” Rostow and Millikan’s notion of directing assistance based on economic prospects rather than on geostrategic priorities was radical for the time.

USAID Administrator Peter McPherson presents information on the Ethiopian famine to President Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office. Also pictured, from left: Counselor Ed Meese, Vice President George H.W. Bush, Chief of Staff James Baker and NSC Director Bud McFarland.

White House

Reorganizing Foreign Assistance

Former President George W. Bush visits the Kasisi Children’s Home in Lusaka, Zambia, on July 4, 2012.

Shealah Craighead / The Bush Center

George Ball delivered his memo on reorganizing foreign assistance to the president on March 4, 1961. The working group was in clear agreement that almost all foreign aid functions should be housed within a single new government agency, and that instead of a series of disconnected projects, development strategies should approach the challenges in recipient countries holistically.

They felt that the new agency had to be field-driven, carrying out its responsibilities through the establishment of country “missions” staffed by a mix of U.S. and local personnel. Kennedy’s advisers further argued that the new agency should direct programs on a multiyear basis, which would permit developing countries, as David Bell put it, “to undertake the kind of difficult political measures, such as raising taxes or accomplishing a land reform program, which needed to be undertaken.”

There was also general concurrence that international economic assistance should be divorced from military aid and that aid should not be conditioned on support for U.S. policies. As Arthur Schlesinger recalled Kennedy arguing, “If we undertake this effort in the wrong spirit, or for the wrong reasons, or in the wrong way, then any and all financial measures will be in vain.”

Major disagreements remained, however, including on the issue of food aid. Food aid, which shipped American food surpluses overseas for use in foreign aid programs, was very important to U.S. farmers at the time. In 1956 food aid purchases by the U.S. government accounted for 27 percent of all wheat exports—a huge market share.

Kennedy and others were starting to see the central goal of food aid as addressing global hunger, rather than just dumping America’s surpluses. They wanted to give the new agency control of food aid, but the Department of Agriculture was reluctant to relinquish the program. In the end, the Department of Agriculture was left in charge of most international food aid because the administration feared any alternative would lead to cuts in the budget.

One more important question to be resolved was the relationship of the new aid agency to the Secretary of State and the State Department. “There was a strong feeling,” David Bell explained, “that aid decisions had been improperly subordinated in the previous arrangement to the views and judgments of the State Department’s assistant secretaries and office chiefs.” It was ultimately decided that the head of the new agency should report to the Secretary of State, but not through any intervening layer of State Department officials. Many at State bristled at not having a closer hold on assistance programs.

Once elected, Kennedy quickly turned to plans to overhaul the foreign assistance program.

On March 22, 1961, Kennedy’s foreign aid message was delivered to Congress. The president wanted a single agency in charge of foreign aid in Washington and in the field, a “new agency with new personnel,” drawn from both existing staff and the best people across the country. Aid would be delivered on the basis of clear and carefully-thought-through country plans tailored to meet local needs. It would be distinct from military aid because “development must be seen on its own merits.” Kennedy urged a special focus on countries that were willing to mobilize their own resources and embrace reform.

Less than a month later, President Kennedy lurched into the botched Bay of Pigs invasion. Yet, paradoxically, this also lent momentum to his calls for an expanded and overhauled aid program. On May 26, Democratic Senator William Fulbright of Arkansas introduced the Act for International Development, the key vehicle for creating the new agency.

But if Congress was willing to accept foreign aid as part of the price of facing global communism, it was not going to give the White House carte blanche in its design. Sam Rayburn, the immensely powerful Democratic Speaker of the House, insisted that support for foreign aid would evaporate if the security and economic dimensions were presented to Congress separately. To secure support on the Hill, Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon informed Congress that 80 percent of economic aid would be spent on American goods and services. Eighty-three members of the House protested the proposal that the agency would get multiyear appropriations. William Gaud, who ran one of USAID’s regional bureaus at the time, saw it as a grievous setback. “An aid program should be a long-term proposition if it is to achieve its ends,” he argued, but instead, “we spend the whole bloody year fighting before the Congress.”

President Kennedy was deeply irritated with the loss of long-term authority. As David Bell explained: “He saw that attitude as limiting the office of the president and the powers of the president in dealing with a turbulent, complicated, dynamic world.”

USAID spearheaded child survival campaigns with its partners, saving millions of lives with a simple intervention.

The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 was signed by President Kennedy on Labor Day, and Congress required the merger of the preexisting assistance agencies into the new agency within 60 days.

Among the debates during the creation of USAID that have continued to play out over the years, none has been more frequent or fraught than that over the agency’s relationship with the State Department. For most of the agency’s existence, State and USAID have sorted out mutual accommodations. From the beginning, however, the State Department disliked the agency’s independence. It continues to fight periodic rearguard efforts to have USAID folded into State. “The aid program is too intimately involved in our foreign relations to allow for the fiction that it is a technical operation which State can delegate to an operating agency,” wrote a State Department official in 1962. Periodically, those efforts to assume greater control over USAID have erupted into messy open conflict, including a merger battle in the 1990s during the Clinton administration and creation of the “F” Bureau in the subsequent Bush administration.

Fueling this persistent debate are sharply divergent views of aid. When he formed USAID, President Kennedy saw its central mission as expanding the number of free-market democracies over the long run, which, in turn, he believed, would make the U.S. more secure and prosperous. The alternative view has been to use aid to gain short-term leverage and influence in countries willing to oppose communism (or terrorism), with commitments to democracy and free markets a second-order consideration.

In short, is foreign aid an instrument of U.S. foreign policy, or is development in and of itself an important aim of U.S. policy? The tension between these two approaches has never been fully reconciled, but the track record of aid when used for instrumental purposes is not a promising one.

Henrietta Fore, the first woman USAID Administrator, is shown here inspecting a humanitarian aid delivery at an Army base outside Tbilisi on August 22, 2008.

Reuters / Gleb Garanich

A Changing World, A Changing Agency

USAID led the international effort to combat the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014.

USAID / Morgana Wingard

USAID’s evolution can be followed over the course of the administrations from Kennedy through Obama. The Kennedy and Johnson administrations saw USAID heavily focused on top-down macro-economic reforms and public administration in key partner countries. The United States was virtually alone as a major bilateral donor, and private capital flows to the developing world were quite low, giving Washington disproportionate influence and impact as developing countries found themselves sometimes squeezed by the harsh realities of Cold War geopolitics. The Green Revolution and the advent of international family planning programs stand as some of the most important legacies of the era. Unfortunately, much of the agency’s good work during this period was overshadowed by the specter of Vietnam and mounting public frustration that U.S. blood and treasure seemed to be wasted in Southeast Asia.

During the Nixon administration, USAID veered on a sharply different course. Discontent with the aid program was high, because of both Vietnam and the rise of a series of U.S.-backed military governments in Latin America. Congress passed the “New Directions” legislation that pushed USAID to focus much more on the needs of the poorest of the poor and rural development. The agency took on a sector-driven approach to producing results in health, education and livelihoods at the village level through a panoply of U.S. NGOs and contractors. New Directions helped stave off those who advocated eliminating the agency, but without a focus on economic reforms, USAID would have a difficult time replicating the early successes of Taiwan and South Korea.

The Reagan administration marked the next important watershed. The foreign aid budget climbed sharply, again driven by Cold War politics, and the agency made a huge push on the health front, becoming the global leader in child survival programs. These programs have always been popular on the Hill and with the public, and health and humanitarian assistance programs over time have come to dominate the agency’s budget and worldview.

By the first Bush administration, USAID had entered into a period of considerable scandal and low morale. The fall of the Berlin Wall triggered a major push by the agency into Central and Eastern Europe.

From climate change to fragile states, USAID’s case load will not disappear any time soon.

The Clinton administration brought a knockdown fight with both Congress and the State Department as Senator Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) led the fight to fold the agency into the State Department. The protracted battle brought steep budget cuts, even as the agency pursued ambitious reforms, and increasingly focused on such issues as women and the environment that had in the past often been an afterthought.

By the beginning of the George W. Bush administration, USAID was a shadow of its former self, deeply wounded by the fights of the previous decade. The aftermath of September 11 brought huge infusions of resources and personnel, new turf battles with the State Department, and complicated missions in Iraq and Afghanistan that often echoed the Vietnam experience. In both of these settings, there was very little willingness to question how, or even if, development would be successful under such conditions. As James Kunder of USAID put it, “The hard lesson from both Afghanistan and Iraq was that development programs are not a good substitute for an effective diplomatic and military strategy.”

The Obama years brought a renewed emphasis on agriculture and innovation, but with a level of ambition often constrained by the continued fallout of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis.

USAID Today

So where does the agency stand after 60 years? Clearly, the need for an effective aid agency has not diminished as the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying economic crisis have shown. From climate change to fragile states, USAID’s case load will not disappear anytime soon. And while foreign aid always remains a lightning rod, it has done enormous good over the years, and the international community has made historic progress in combating extreme poverty, hunger, illiteracy and despair. While the United States was one of just a handful of donors in 1961, 2019 saw more than 40 countries offering bilateral aid—and virtually all of them were former recipients of U.S. assistance.

Perhaps there is no better reflection of how America engages with the world than its foreign aid program. The spirit of the United States has always deeply imbued this endeavor: a restless, entrepreneurial, sometime arrogant conviction that the face of the world can be transformed by assisting like-minded nations and encouraging them to embrace free markets and free ideas.

Read More...

- “Book Event: The Enduring Struggle: A Conversation with John Norris,” CSIS, September 9, 2021

- “Enduring Struggle: Why USAID Plays a Critical Role in the National Security Realm,” by Daniel Runde, The National Interest, August 4, 2021

- “USAID: A history of US foreign aid,” by Devex