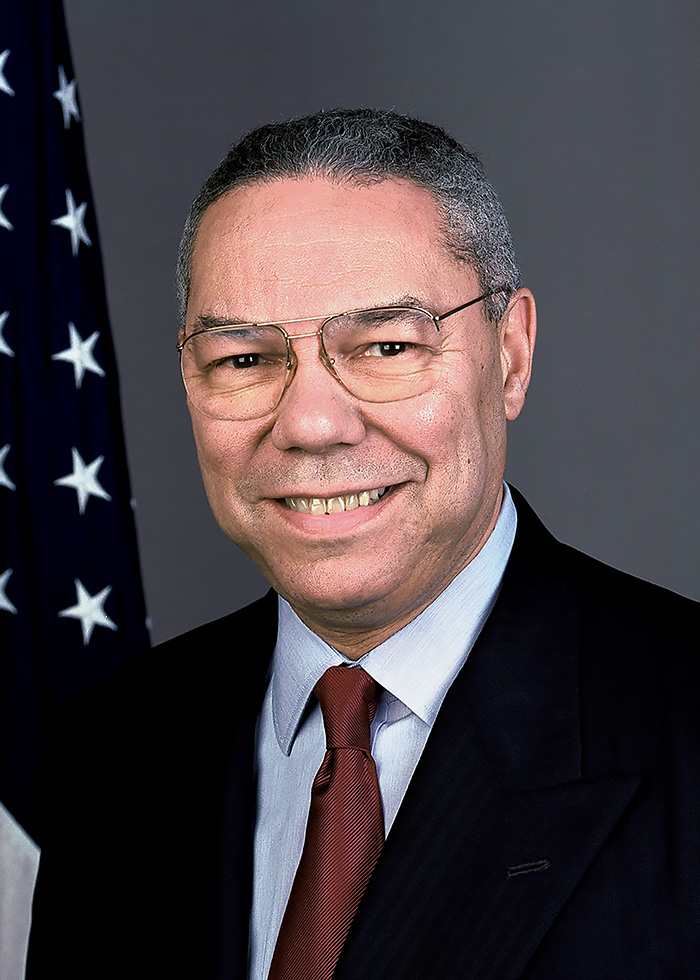

Lessons in Leadership: Colin Powell, 1937-2021

BY MARC GROSSMAN

Official photo of Secretary of State Colin Powell, 2001.

U.S. State Department

Although I did not realize it at the time, I began my 36-year apprenticeship in the values and techniques of leadership the first time I met the late Colin Powell, then Major General Colin Powell, at NATO headquarters in Brussels in 1985. Powell was military assistant to U.S. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger while I was the deputy director of NATO Secretary General Lord Carrington’s Private Office. Powell had come to report that Weinberger would be late for his meeting with Carrington. Being the most junior person in the neighborhood, I got the task of reporting this to Lord Carrington, who was a fanatic about being on time.

Carrington told me to tell Powell that since “Cap” was late, he would not be having a private meeting with the secretary general. When I conveyed this news, Powell stared at me, told me he was sure I could reverse this decision and sat down on a couch to wait until I did. No raised voice. No drama. Lucky for me, Powell did not remember this incident years later. He also turned out to be a stickler for being on time.

Command Encounters

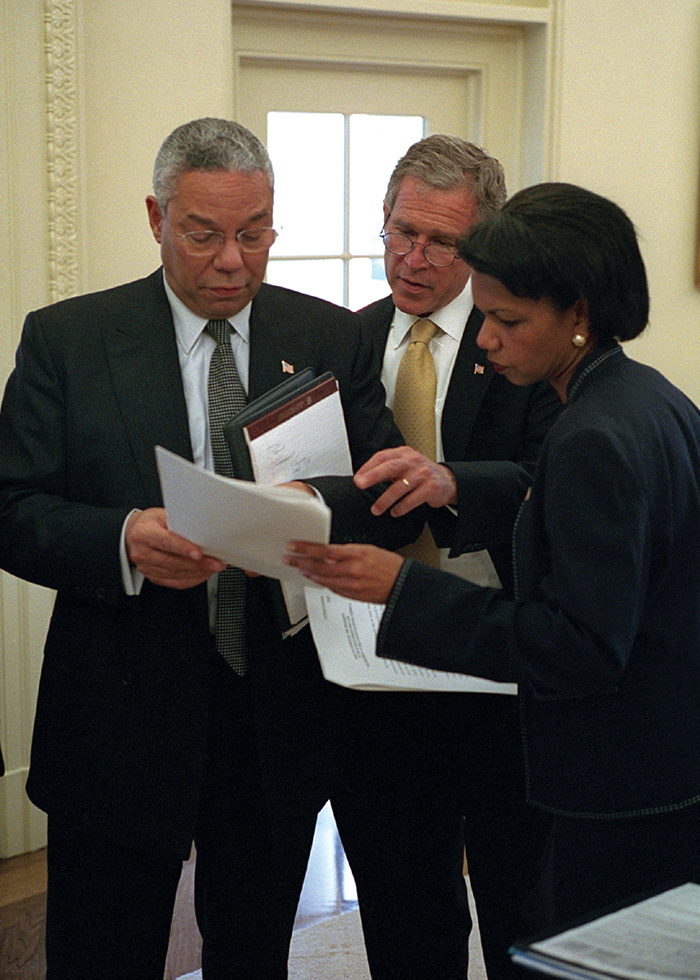

Secretary Powell looks over a brief with President George W. Bush and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice in the Oval Office, before meeting Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov, Sept. 19, 2001.

National Archives and Reports Administration

I next encountered four-star General Powell in the early 1990s when I was the deputy chief of mission in Turkey, and he visited Ankara during the Gulf War on his way to the Turkish air base at Incirlik to see U.S. forces stationed there. After dinner at the ambassador’s residence, Powell realized that one of his aides had failed to bring the full combat uniform he needed for the next day’s travel to Incirlik. Powell told those of us who had been summoned to solve this problem that he knew we would do so by morning, which we did, by borrowing stars from two major generals and combing the local U.S. military community for a pair of the right-size boots.

Another lesson in command: Stay calm. Expect others to do their jobs and meet your expectations. It was also a lesson for those doing the work: Don’t panic. Focus on the task in front of you.

As Director General of the Foreign Service, I next met then–Secretary of State Designate Powell in late 2000. On his first day at the State Department, he invited me to come see him. “What can I do to make a difference for the people here?” he wanted to know. Thanks to the creative thinking of experts in the Director General’s office, I told him that we needed 15 percent more people so that we could be as serious as the military about professional education. I pitched what we called the Diplomatic Readiness Initiative, a plan to hire 1,200 people over three years. He committed right then and there to putting it in the budget. And it got done.

More leadership lessons: Reward new thinking and preparation, including always being ready for what the opposition might be planning. Show confidence in and then support the people who work for you. Decide.

There would be many more lessons during the years it was my privilege to be Secretary Powell’s under secretary for political affairs, but Sept. 11, 2001, defined our tenure. On that dreadful day, Secretary Powell was in Peru at a meeting of the Organization of American States. Deputy Secretary Richard Armitage asked me to meet the Secretary at Andrews Air Force Base on his return in the afternoon. When the Secretary asked me what I knew, I did my best to convey the facts. We then sat silently on the way to the White House as Powell considered the present and the future. When he returned to the State Department late that night, he had the outline of our plan to move forward.

Secretary of State Colin Powell walks with Indonesian President Susilo Yudhoyono (on Powell’s immediate left) after departing his plane in Banda Aceh, Sumatra, Indonesia, on Jan. 5. 2005, days after the deadly tsunami struck. Powell and Yudhoyono met to discuss future U.S. aid to the area.

PJF Military Collection / Alamy

A Confident Visionary

Colin Powell was a committed optimist.

■ He believed in the goodness of our great nation and in its positive role in the world. It is not an accident that he was the founding chair of an organization called America’s Promise. He believed in the Army in the way I believe in the Foreign Service. I was sorry that he went back to being General Powell after his service as Secretary, but I understood why.

■ He believed in education as the foundation of a better future. He always used the words “professional education” to describe the work being done at the Foreign Service Institute. He would often compare his years of professional education in the Army to my several months of training (not counting language training) in the Foreign Service. He expanded his knowledge by acting on his belief that there is something valuable to learn from everyone.

■ He believed in the power of saying “thank you.” This was his habit at the State Department and on his visits to our embassies overseas. He never forgot to recognize the crucial part families play in the success of the State Department.

■ He believed in young people. This is the core principle of America’s Promise. You can also grasp this belief in the statement made on his death by the dean of the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership at the City College of New York, Andrew Rich: “When it came to college, it was CCNY or nowhere. He found ROTC here, and he discovered his purpose and direction. General Powell committed himself to every student who walked through our doors. He’d hear their stories and tell them his own. He would encourage them to work hard and pursue their dreams. He always reminded them—and all of us—that ‘they’re just like I was’ some 65 years ago.”

AFSA welcomes the new Secretary of State on the opening pages of the March 2001 AFSA News in the FSJ.

Colin Powell was not perfect. He fulfilled his duty in October 2002 to make the case at the United Nations for an invasion of Iraq, despite his doubts (which turned out to be well founded) about the intelligence supporting his presentation. He made the case as carefully as he could, but he knew then that his obituary would prominently feature this act. And so it did.

In the years after his service at the State Department, General Powell invited several of us to lunch from time to time, including this past summer. It was a pleasure to see his smile and to hear his stories.

A Fitting Tribute

Our collective memory is that Secretary Powell was a champion of the Foreign Service. It is manifestly true that he did an enormous amount for the Service and for the State Department. But he was also realistic about the Foreign Service’s strengths and foibles. He admired the Foreign Service, especially its individuals; but he knew change was required. He challenged us to be better. To take professional education seriously. To be more diverse and inclusive. To respect the Civil Service. To change a risk-averse culture. These issues sound familiar because they are still relevant. It would be a fitting tribute to Colin Powell to make serious progress on all of them.

Read More...

- “Colin L. Powell’s Thirteen Rules of Leadership,” State Department, October 18, 2021

- “Colin Powell, The Humble American,” by Robin Wright, New Yorker, October 19, 2021

- February 2005 Foreign Service Journal on Colin Powell Handoff