A Labor of Love: Rediscovering State’s Lost History

A project to unearth the lives and legacies of the earliest diplomats is awakening a shared understanding of the U.S. Foreign Service and its history.

BY LINDSAY HENDERSON

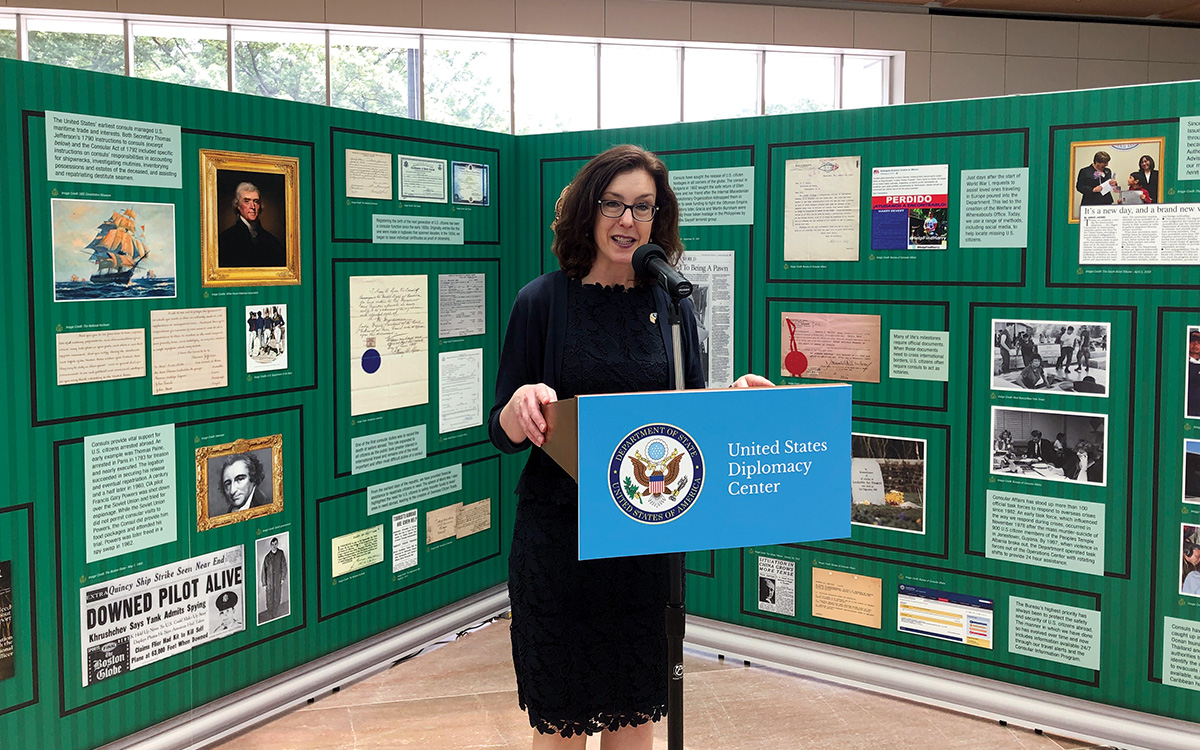

FSO Karin Lang gives remarks at the exhibit, “From Pirates to Passports: A Timeless Commitment to Service,” at the U.S. Diplomacy Center in May 2019.

Courtesy of Lindsay Henderson

Excellent documentation has captured the State Department’s work since 1789, but less well preserved is the history of the individuals who made U.S. diplomacy possible. Working together and pooling resources, some department employees are dedicated to changing that.

Did you know that the first rhinoceros brought to the United States was shipped home by a U.S. consul (the curiously named Marmaduke Burrough) on home leave between his overseas tours in India and Mexico in June 1830? Or that the U.S. government first started adding photos to passports in 1914 after a German spy was caught using a purloined U.S. passport in the United Kingdom?

Neither did we until recently, when a small group of consular professionals sought to document the human side of our history. Who were the individuals who built and ran the department? Who opened and closed posts, conducted negotiations, reported on political and economic conditions, provided services to their fellow citizens in need and lived—and sometimes died—in the Foreign Service? Read on to learn about a handful of these fascinating figures whose lives and legacies we’re rediscovering. But first, we would like to share how this project took shape.

From Pirates to Passports

When presented the opportunity in the spring of 2019 to develop an exhibit for the United States Diplomacy Center (now the National Museum of American Diplomacy, or NMAD) on the history of consular work, a small but motivated group of FSOs—led by Kelly Landry, William Bistransky and Karin Lang—gathered a team of department employees, myself included, to plan it. Our goal was to identify predecessors who personified the values that drew us to the profession, and to share their stories to inspire others. At the time, our collection of original artifacts was slim, and our resources sparse, so we worked quickly in Washington and with overseas posts to secure these artifacts to document our history before it disappeared.

In what rapidly became a passion project, our team reached out to colleagues across the department, working closely with the Office of the Historian, the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, the National Archives and Records Administration, the Smithsonian Institution and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Without a budget, and at our own initiative and expense, we personally collected items related to department history from private vendors in more than 30 countries, an effort that produced an extensive collection of antique passports, visas, photos, documents and other items; and we asked our consular colleagues in the field to check their closets and basements at post. Through this process, we discovered just how little we know about the State Department personnel who came before us and built the department into what it is today—which is particularly important as we envision the department of the future.

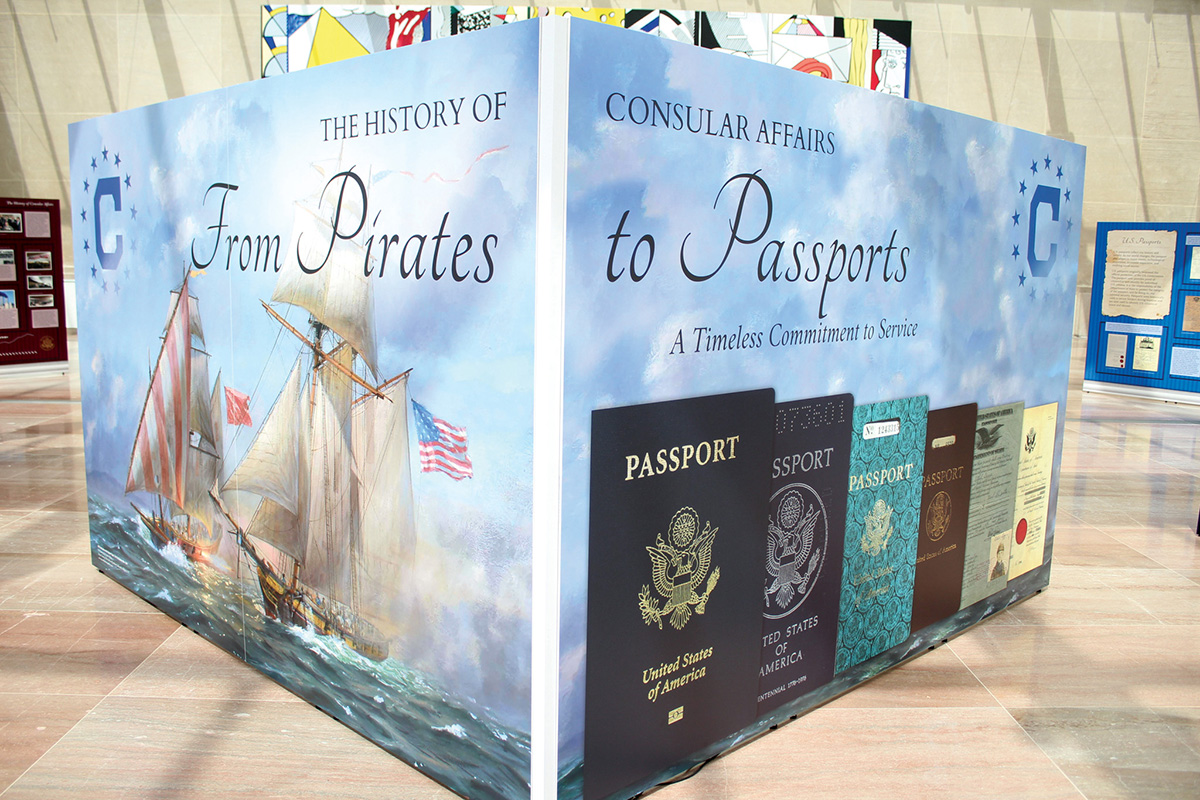

The result of our initial effort was the May 2019 NMAD exhibit, “From Pirates to Passports: A Timeless Commitment to Service,” which commemorated the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Bureau of Consular Affairs and featured information and artifacts from consular history from 1780 to the present, covering passports, visas and overseas citizen services. Showcasing the visually stunning work of the bureau’s in-house designers, Jodie Tawiah and Christi Hairston, this exhibit impressed the many active-duty and retired State Department employees who visited it, including Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. We are now working with NMAD to make a digital version of the exhibit available online in the coming months. And this is only the beginning.

Interest from across the department was so strong that we realized we needed to find ways to permanently document what we found and keep those interested involved. We created the CA History Project, a Facebook group for current and retired department employees to share information. And this has led to a number of follow-on projects, including recent efforts to help AFSA identify department personnel who died while serving abroad whose names were not previously recorded on the AFSA Memorial Plaques (which I will refer to here as “the memorial”) in the C Street lobby. We are now attempting to identify the locations of gravesites of department employees who were buried abroad, coordinating with the field to document and photograph their locations and, when necessary and if possible, arranging for cleanup of these gravesites. We intend to work with both AFSA and the diplomacy museum to make these locations known and accessible to the Foreign Service community.

We are also working on a video about two brave consular officers—Hiram Bingham IV and Myles Standish. While we were planning the exhibit, Consulate General Marseille and Embassy Paris informed us that they found a World War II–era register of passport services provided to U.S. citizens, a unique document related to the efforts of Bingham and Standish to issue visas to more than 2,500 Jewish refugees in France. Their actions were contrary to department policy at the time, and they saved thousands of lives in the process, personally extracting some individuals from a concentration camp and hiding them in their own homes before they could be smuggled to safety. Both officers eventually lost their jobs because of their efforts. The aim of the video is to share the story of courage of these two officers, as well as underlining the register’s importance to department and Holocaust scholarship. (For more on Bingham, see the June 2002 FSJ.)

Commemorating the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Bureau of Consular Affairs, the USDC exhibit featured information and artifacts from consular history from 1780 to the present, covering passports, visas and overseas citizen services.

Courtesy of Lindsay Henderson

Rediscovering Forgotten Colleagues

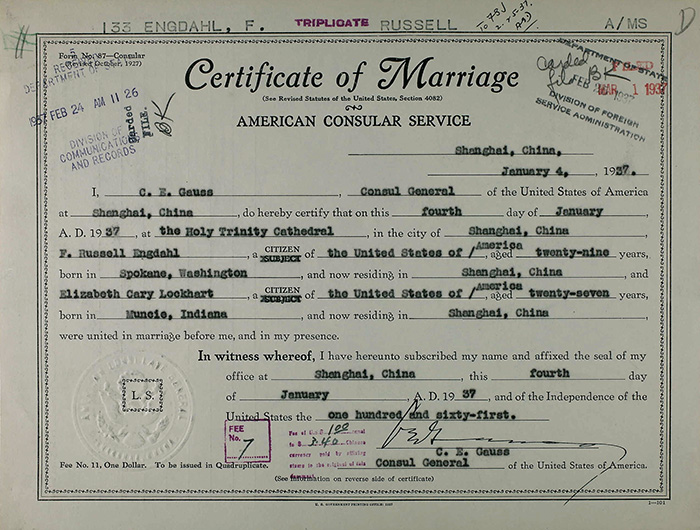

This artifact is the 1937 marriage license of Vice Consul Felix Russell “Russ” Engdahl and Elizabeth Cary Lockhart. Research revealed that Russ Engdahl died tragically in May 1942 as a prisoner of war in a Japanese POW camp. His wife went on to become vice consul in Shanghai, returning to the city where they had met and married. His name was recently added to the AFSA Memorial Plaques in C Street lobby.

ancestry.com

Between the 1790s and 1960s, the State Department tracked more than 6,500 consular and other diplomatic assignments on handwritten index cards. Now, we are in the planning stages of developing an online, publicly accessible database, including an indexed version of these consular cards, with links to photographs and information about the individuals listed when available. The public will be allowed to contribute their own materials related to these employees to further flesh out biographical details.

Of the many index cards, 807 cases of overseas deaths were recorded; we found most of them did not qualify to be added to the memorial. Either the individuals had died of natural causes or diseases that could have been contracted within the United States, or they had died shortly after being medevaced back to the country. While researching the causes of death to determine whether they met AFSA’s criteria for inclusion, we uncovered stories of service that deserve to be told, even if the individuals are not listed on the memorial.

Among those names we reviewed, we found a reference to the death of an early U.S. consul in Peru, J.B. Prevost, who probably died of a combination of natural causes and exposure in November 1825 on the road between Arequipa and Cusco, his remains tossed out of a roadside shelter into the snow. He was later buried nearby by a concerned American sent to find him. Our research revealed that this consul was, in fact, John Bartow Prevost, the stepson of Aaron Burr and a member of what is now the Louisiana Supreme Court. While he has a grave marker in the family plot in Ridgefield, New Jersey, we aren’t entirely sure if Prevost’s remains were ever repatriated. We hope to find out through additional research.

In 2007 another mystery presented itself. That year, FSO Paul Stronski discovered a gravesite in Hong Kong with a handwritten marker that read “F.R. Engdahl, U.S. Consul.” Engdahl’s name was not listed on the memorial, however, and when Stronski later mentioned this in his morning carpool, a colleague determined to find out why. FSO Jason Vorderstrasse’s subsequent research revealed that Felix Russell “Russ” Engdahl, born in Spokane, Washington, to Swedish immigrants in 1907, died tragically in May 1942 as a prisoner of war in a Japanese POW camp. He had fallen down a flight of stairs. Engdahl’s name was recently added to the memorial, thanks to Vorderstrasse’s extensive efforts to document his service and sacrifice. Vorderstrasse even located the flight of stairs at the former camp that contributed to Engdahl’s fall (as described in the June 2009 FSJ).

Our research also led us to the story of Engdahl’s wife, Elizabeth Cary Lockhart “Lee” Engdahl, which is perhaps even more compelling and deserves its own due. Born in 1909 in Muncie, Indiana, and a one-time student at Wellesley College, she married Russ Engdahl in 1937 in Shanghai, where he was serving as a consul and she lived with her parents while her father worked as an economic adviser to Chiang Kai-Shek. The newlywed Mrs. Engdahl was forced to flee to Manila only a few months later when Japan invaded China. She returned to Shanghai in December 1937, and then went to the United States with Russ in April 1939, presumably remaining there when he was sent to Hong Kong in late 1941 on courier duty.

In 1942, Mrs. Engdahl began work at the State Department—probably out of financial necessity when her husband died—as a file examiner in the Division of Communications and Records, where she served until 1946. It is not difficult to imagine the stress she must have been under. Not only had she lost her husband under horrific circumstances, but her younger sister, brother-in-law and two young nieces were interned by occupying Japanese forces in Shanghai at the same time.

Nevertheless, what must have been a very painful time in her life became a catalyst to serve. In 1946, the widowed Mrs. Engdahl was appointed vice consul in Shanghai, returning to the city where she met and married Russ—and to his former job. Her grit and courage to take this step were extraordinary, particularly for a woman at that time. Not only did she complete her tour in Shanghai, but she went on to serve as a visa officer in Tehran, Paris, Vienna, Washington, D.C., and Montreal, as well as probable TDY assignments in Salzburg, Santo Domingo and Brussels. She retired as chief of field operations in the Visa Office in Washington in 1969. She never remarried.

The Complicated Legacy of One Particular Officer

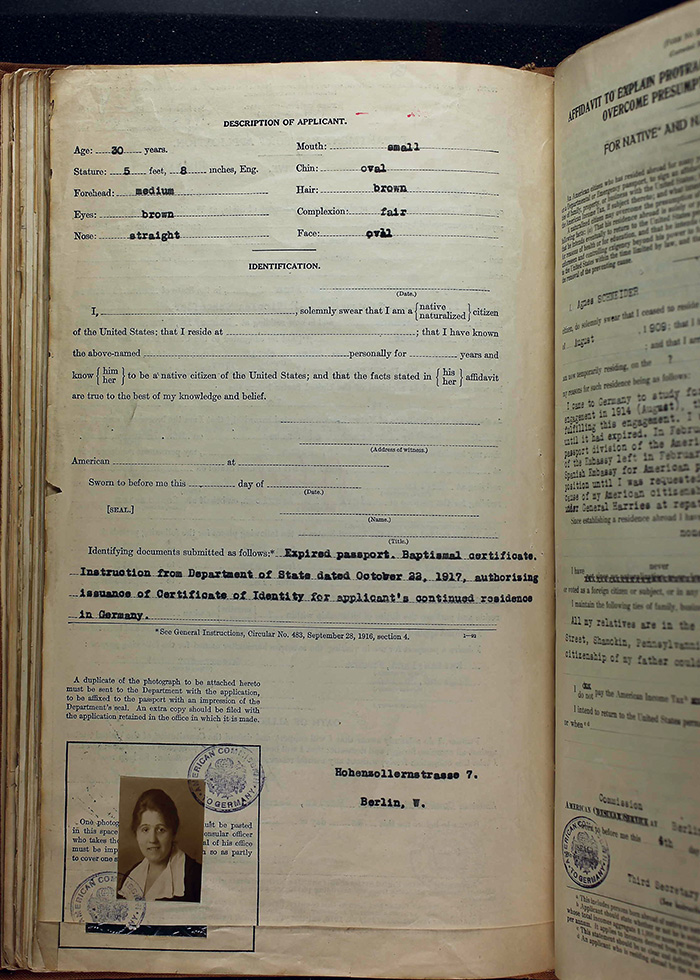

Before her days as “Spider Schneider” in 1950s’ Paris, here is a 1920 passport photo of Agnes Schneider, who would work at U.S. Embassy Berlin as a clerk in the consular section for the better part of the next two decades.

ancestry.com

Other historical State employees were brought to our attention by academics and relatives who contacted the department in search of information, and one officer, in particular, left a complicated, yet intriguing legacy that continues to unfold. Agnes Schneider served as the consul for passport services in Paris from October 1944 until her retirement in 1960. Serving as hostess for anyone who was anyone (among her guests were General Dwight Eisenhower and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor) at frequent salons at her home in Paris’ Hôtel de Crillon, she was well known throughout the expatriate community in France.

Ms. Schneider was infamous for summoning Americans she suspected of harboring communist sympathies to the consular section at Embassy Paris on a pretext, then confiscating their passports. Known throughout the local community as Spider Schneider, she also took a dim view of anyone requesting to renounce their U.S. citizenship and was consequently named in several lawsuits during the era. Her actions mirrored those of the infamous Passport Office Director Frances Knight, a close friend of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis.), who made sure those at home with rumored communist ties would not receive a passport at all.

While we may find these actions reprehensible today, Agnes Schneider’s backstory is far more complicated than one might expect. Raised in the small town of Shamokin, Pennsylvania, as the fifth of eight children in her parents’ large boarding house, Agnes was a gifted soprano soloist and was sent to Berlin at age 17 to train for the opera. In Berlin, she was taken in by the Israel family, wealthy owners of one of the largest and oldest department stores in the city and patrons of the arts, who essentially raised her from then on as part of their family.

When the outbreak of World War I dashed her opera dreams, Ms. Schneider took a job at Embassy Berlin as a clerk in the consular section, where she worked for most of the next two decades. In fact, when the United States entered World War II, she was one of the last Americans left working at the embassy, staying until she was also arrested and interned by the Nazis with other U.S. diplomatic staff in Bad Nauheim. She remained in detention until they were exchanged for German prisoners in May 1942.

Instead of sailing for New York with the rest of her colleagues, Ms. Schneider sailed for London, where she began work at the U.S. embassy and reconnected with the Israel family, who had relocated to London after their oldest son, Wilfrid Israel (a friend of Albert Einstein), coordinated and helped finance the Kindertransport, which relocated German Jewish children to the United Kingdom in 1938-1939. Sadly, Wilfrid Israel’s plane was shot down off the coast of Portugal in March 1943 while he was working on plans to save Jewish children in Vichy France. The last person he was known to have spoken with in London on the evening prior to his final departure was Agnes Schneider.

Given their close relationship, it is likely that Ms. Schneider had a role in helping with the Kindertransport effort, although we have not yet been able to discover any proof. Her obituary also mentions that she had helped several Jewish families escape Germany. What is evident from our research is that she was very human, and her legacy is far more complicated than the “Spider Schneider” moniker from 1950s Paris would suggest.

Our goal was to identify predecessors who personified the values that drew us to the profession, and to share their stories to inspire others.

Have we piqued your interest? If you have a great department history story or item to share, if you are willing to do research at your post, or transcribe handwritten antique documents, or if you simply enjoy department history trivia, please join us on Facebook in the “CA History Project” group (we ask that you answer the security questions so we know who you are). Not on Facebook? Feel free to contact me by email, and I will gladly introduce you to the rest of the team.

A healthy community needs a shared understanding of its history—both the positive and negative aspects of it—to chart a course forward. Through researching and documenting the lives of those who came before us—and making that information digitally accessible to ourselves and to the public—we can strengthen our understanding of who we are, how we got here and where we are going next.

Read More...

- “America’s Overlooked Diplomats and Consuls Who Died in the Line of Duty,” by Jason Vorderstrasse, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2020

- “The Foreign Service Honor Roll,” by John K. Naland, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2020

- “‘From Pirates to Passports: A Timeless Commitment to Service’ Exhibition Opens at the National Museum of American Diplomacy,” State Department, June 6, 2019