The Rise of the New Russia

This tour d’horizon from the fall of the Soviet Union to today—including hopes, disappointments and missed opportunities—puts U.S.-Russia relations into perspective.

BY LOUIS D. SELL

From an exercise involving Lithuanian and NATO forces held in Lithuania in 2016.

James Talalay

Vladimir Putin famously described the collapse of the USSR as “the biggest geopolitical tragedy of the [20th] century”—quite a claim when one considers the competition: two world wars and the Holocaust, for starters. But the Russian president’s remark illustrates why it is impossible to understand Putin and the country he leads without also understanding how Russians view the collapse of the USSR and its aftermath.

The Soviet Union fell in 1991 without any of the events that have generally accompanied imperial collapse in the past— military defeat, foreign invasion, internal revolution and the like. It came, moreover, only a short time after the country appeared to be at the pinnacle of international power and prestige. Recall nuclear arms agreements that many interpreted as signaling Moscow’s achievement of strategic parity with its American rival and the expansion of Soviet power during the 1970s into areas far beyond traditional areas of influence. Moscow’s confidence led Foreign Minister Gromyko to say in 1972 that “no international problem of significance anywhere can be resolved without Soviet participation.”

In reality, the USSR was a superpower only in the military sense. Its armed might rested on a sclerotic political system and an inefficient economy, barely half the size of its American rival. When Mikhail Gorbachev took office in 1985 after the deaths of three aging leaders over the previous three years, he had had the wisdom to understand the need for reform and the courage to begin it. But Gorbachev had no plan, and he dithered when the reforms he unleashed threatened to go beyond the “socialist alternative” to which he remained committed until the end.

A Twilight of Pro-American Enthusiasm

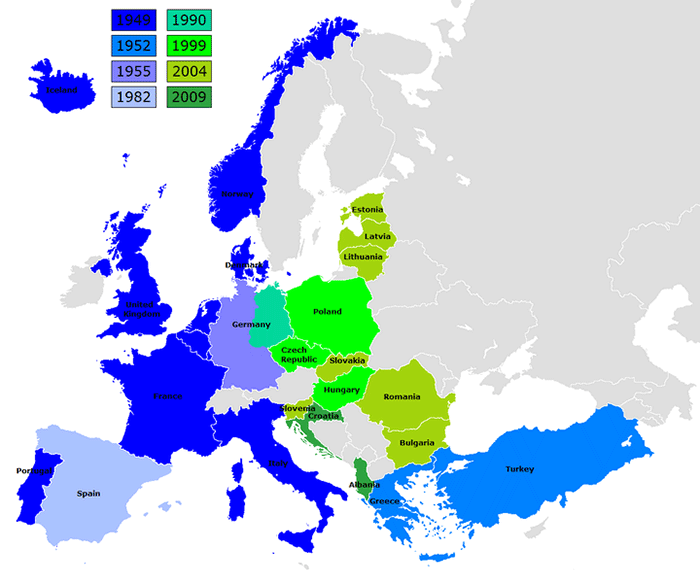

NATO expansion by year.

Wikimedia Commons / Image by Kpalion

The August 1991 coup marked the end of Gorbachev and the USSR, even though both managed to hang on for a few more twilight months. Those fortunate enough to be present remember the climate of euphoria that engulfed Moscow after the coup. People persuaded themselves that life would soon change for the better. The country had been through tough times but had emerged with hope from the crisis of the coup and the long nightmare of communism.

Russia would remain a superpower, but it would join the other members of the world community as a “normal” country. Democracy was on everybody’s lips. People believed that with the Communist Party swept away it would be easy to graft the institutions of democratic governance onto the Russian body politic. Russians, after all, were a well-educated and talented people. Soon Moscow would take its proper place with New York, London and other world centers.

An outpouring of positive feelings toward the United States accompanied the post-coup euphoria. It was assumed that Russia and the United States would remain the world’s two leading nations but now as friends and partners, not rivals. To walk into a Russian office and be introduced as an American diplomat was to be greeted by smiles, enthusiastic handshakes and often a warm embrace.

Looking back, this brief window of pro-American enthusiasm was probably unsustainable, and even at the time there were signs of strain. Over the winter of 1991-1992, as basic supplies dwindled in Moscow, the U.S. airlifted emergency humanitarian aid. On one occasion, my son and I helped unload a massive C-5A cargo aircraft and accompanied a convoy of food and medicines to a Moscow hospital. As the material was unloaded and a number of empty boxes turned up, the hospital director flew into a rage, accusing us of stealing some of the supplies and staging a show.

Back at the embassy the air attaché told me that empty boxes were used to distribute the load in a balanced fashion throughout the aircraft. The next day when I called the director to explain the situation he expressed gratitude for the U.S. assistance, but added that he also hoped we understood just how difficult it was for a Russian to be in the position of accepting aid from the United States, however well-intentioned.

Twenty-five years later Putin has constructed a narrative of Western perfidy that is the foundation of his appeal to the Russian people. In reality, plenty of mistakes were made in Moscow and abroad.

Almost everyone involved in Russia after the Soviet collapse— Russians, as well as foreigners—underestimated the extent of the political, economic and social difficulties that needed to be overcome. To some extent, this was a consequence of the structure of the Soviet system itself, where basic information was either lacking or falsified. No one really understood, for example, how large and intractable the massive Soviet military industrial complex was—or how difficult, and in many cases impossible, it would be to find ways to restructure it into more productive uses.

Looking back, this brief window of pro-American enthusiasm was probably unsustainable, and even at the time there were signs of strain.

Similarly, everyone underestimated the difficulty in establishing a viable democracy in a society where it had never existed before. Institutions were created and elections were held, but a genuine democratic culture—founded on toleration, compromise and rule of law—could not be created overnight.

Both Russian reformers and their Western supporters overpromised and underperformed. Largely for domestic political reasons, U.S. administrations exaggerated the size and significance of American assistance. Russians received a lot of advice—almost all of it wellmeaning, and some of it good—but too much of it amounted to applying outside models to stubborn Russian reality.

Missed Opportunities

In retrospect, it also seems clear that the United States missed opportunities to engage with the new Russian authorities in areas of potential trouble. Washington had little choice but to back embattled Russian President Boris Yeltsin in 1993, when he was compelled to suppress an armed uprising by hard-line parliamentary opponents. But Yeltsin never recovered, emotionally or politically, from the trauma of having to send tanks into the street to shell fellow Russians, and in subsequent years his actions became increasingly erratic.

In 1993 Washington turned a blind eye when Yeltsin introduced a much-needed new constitution through a questionable vote count. It did the same in 1996, when dubious deals that effectively turned over large portions of the Russian economy to the new class of rich Russian “oligarchs” provided funds to help Yeltsin eke out a victory in that year’s presidential election. The result associated U.S. policy with a government that many Russians saw as responsible for the poverty and turmoil of Russia in the 1990s.

In the field of national security, the United States could never decide whether its primary objective was to help create a democratic and confident Russia as a full partner in the post-Cold War world or to build up the former Soviet states as independent counters to a possibly resurgent Moscow. The United States ended up trying to do both and accomplishing neither well.

The two key security challenges the West faced in the decade after the Soviet collapse were dealing with the nuclear legacy and devising security architecture to meet the challenges of the post-Cold War environment. The United States and Russia engaged effectively in the nuclear arena, where they had a clear common interest. Numbers of nuclear weapons were dramatically reduced, and the two countries cooperated for many years to enhance security for Russian nuclear weapons—at least until 2013, when Putin canceled the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, also known as the Nunn-Lugar Program, which was the foundation of this effort.

On security architecture, the Western response was to extend the existing Cold War system of military and economic alliances eastward, rejecting—probably with good reason—the alternative model of creating a new system. It has become an article of faith in Putin’s Russia that the expansion of NATO into Eastern Europe and some former Soviet republics violated commitments made during the negotiations on German unification. The historical record provides no support for these beliefs, but the question remains whether NATO expansion was wise.

Talk of a new Cold War is unrealistic, if only because Russia remains incapable by itself of mounting the sustained global challenge to Western interests that the USSR did.

In 1997, I visited Moscow for a seminar devoted to NATO expansion. In tones that ranged from pleading to anger, Russian diplomats, politicians and journalists warned that the expansion of NATO into countries that only a few years earlier had been part of the Soviet security zone would strengthen the strong resentment against the West that was already boosting the rise of xenophobia and authoritarianism across the Russian political spectrum.

Opposition in Moscow does not, of course, necessarily mean that NATO expansion was wrong. Membership in NATO and the European Union was critical in integrating former Eastern European communist regions into a united and democratic Europe. But the failure to work out some mutually acceptable form of cooperation between NATO and Russia was a major setback. Russia, itself, bears much of the blame for this failure. Its threatening posture to its neighbors, aggressive intelligence activities and the questionable caliber of some Russian officials sent to NATO headquarters in Brussels left the impression that Moscow had little interest in ending East-West confrontation.

Nevertheless, anyone seeking to understand why Putin has enjoyed such success in Russia should start with the sense of humiliation many Russians feel at the image of NATO forces perched astride borders that once formed part of the internal boundaries of the Soviet Union.

In the early post-Cold War years the new Russian government, aware of its own weakness, stayed close to the United States on international issues. But, with its long-time Soviet rival vanished, Washington found it all too easy to dismiss Moscow’s concerns when these conflicted with its own priorities. The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty II, signed in January 1993, is an example. It mandated the most sweeping reductions in nuclear arms achieved up to that time. Russian experts calculated that START II would save Moscow the equivalent of approximately $7 billion, but the optics of the deal looked bad to many Russians. In particular, it forced Moscow to give up a substantial part of its intercontinental ballistic missile force, whose elimination had been a U.S. objective since the inception of arms control negotiations.

START II was a good deal for both sides, but it also reflected the realities of the time. The United States made clear that if Moscow did not go along, Washington would maintain its nuclear forces at a level greater than the impoverished Russia of that era could afford. That perception of imbalance is one reason why START II never entered into force. After the treaty was concluded, U.S. Ambassador to Russia Robert Strauss told his good friend U.S. Secretary of State James Baker III: “Baker, you didn’t leave those folks enough on the table.” It was a shrewd remark that might serve as a good summation of U.S. policy toward Russia in the years immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Meeting Moscow’s Challenge

So what do we do now? Talk of a new Cold War is unrealistic, if only because Russia remains incapable by itself of mounting the sustained global challenge to Western interests that the USSR did. Putin has impressively restored aspects of Russian military power, but his modernization program came after two decades of post-Cold War neglect. Russia remains far behind the United States in almost every category of military capability—and in most other measures of global power. Its declining population is less than half that of the United States, while its economy is roughly one-quarter the size of the American.

On the other hand, it is equally important not to underestimate the seriousness of the Russian challenge. Aided by the dearth of leadership in Washington and disarray in Europe, Putin has launched something of a quasi-war against the West and the United States, in particular. The Russian offensive unfolds militarily in Ukraine and in Syria, through disinformation and aggressive cyber subversion, and through efforts to create what amounts to a global coalition of authoritarian, anti-Western regimes. It is hard to say how far Putin intends to go with this campaign. There is no master plan for global conquest in Putin’s Kremlin any more than under the Communists. Nevertheless, we have to assume that Moscow will take advantage of targets of opportunity it sees as worth the risk to damage the United States.

Washington needs to determine what its vital interests are vis-à-vis Moscow and take effective steps to protect them.

Even at the height of Cold War confrontation, the United States and the USSR managed to cooperate in areas of vital mutual interest such as nuclear arms control, and this needs to continue. But it is an illusion to believe there can be real cooperation in crisis areas such as Syria, where one of Moscow’s underlying objectives in aiding Assad is to humiliate the United States.

Washington needs to determine what its vital interests are vis-à-vis Moscow and take effective steps to protect them. If Ukraine is truly where we want to draw the line, we should provide Kyiv the aid it needs to rebuild its economy and the real military assistance it needs to defeat pro-Russian rebels in the east. The outline of a deal involving autonomy for eastern Ukraine has been present since the beginning of the crisis, but will not be achievable until Moscow is convinced it cannot secure its broader aims through the use of force. At the same time, we need to make it clear that if Ukraine proves unable or unwilling to generate the necessary internal reforms, we are prepared to walk away. In the murky world of cyber conflict, we need to be prepared to inflict equivalent damage on Moscow, hopefully as a first step toward ending or at least regulating actions in this area.

Responding to Russia’s challenge does not necessarily mean a renewal of endless confrontation. Once Moscow is convinced that it cannot continue its anti-U.S. offensive cost-free, negotiated solutions may become possible. These will require some attempt at understanding the vital interests of the other side. NATO helped integrate former communist countries of Eastern Europe into the Western world, but it is time to acknowledge that expanding NATO membership into former Soviet republics was a bridge too far—both in terms of Moscow’s reaction and the alliance’s ability to exercise its defensive functions.

NATO cannot honorably step away from the commitment it made to the Baltic states, although the alliance needs to give some serious thought to whether variants of the “trip-wire” strategy that worked with West Berlin will also be enough in the Baltics. But NATO should acknowledge the obvious truth that neither Ukraine nor any other former Soviet republic will ever become a NATO member, even as we make clear that we will hold Moscow to its obligations to respect their independence.

Finally, although it is beyond the scope of this article, the United States needs to get its domestic house in order. The dysfunctional U.S. political system is blocking any effort to discuss seriously, let alone resolve, problems that afflict us at almost every turn—looming fiscal crisis in several long-term budgetary areas; decaying physical infrastructure; neglected human infrastructure in medical care, education and minority communities; the tragedy of gun violence; and more.

The West won the Cold War because its political, economic and social system proved superior to that of its communist rival. Twenty-five years later, the chief reason that obscure KGB Lt. Col. Vladimir Putin and his cronies are able to challenge the United States is that the American system seems incapable of generating effective leadership at home and is no longer attractive to countries abroad. Changing this dynamic is a precondition for Washington to regain its proper role of leadership in a revitalized democratic world, with the will and the resources to meet Moscow’s challenge.