Operation Allies Refuge: The FS View from the Front Lines

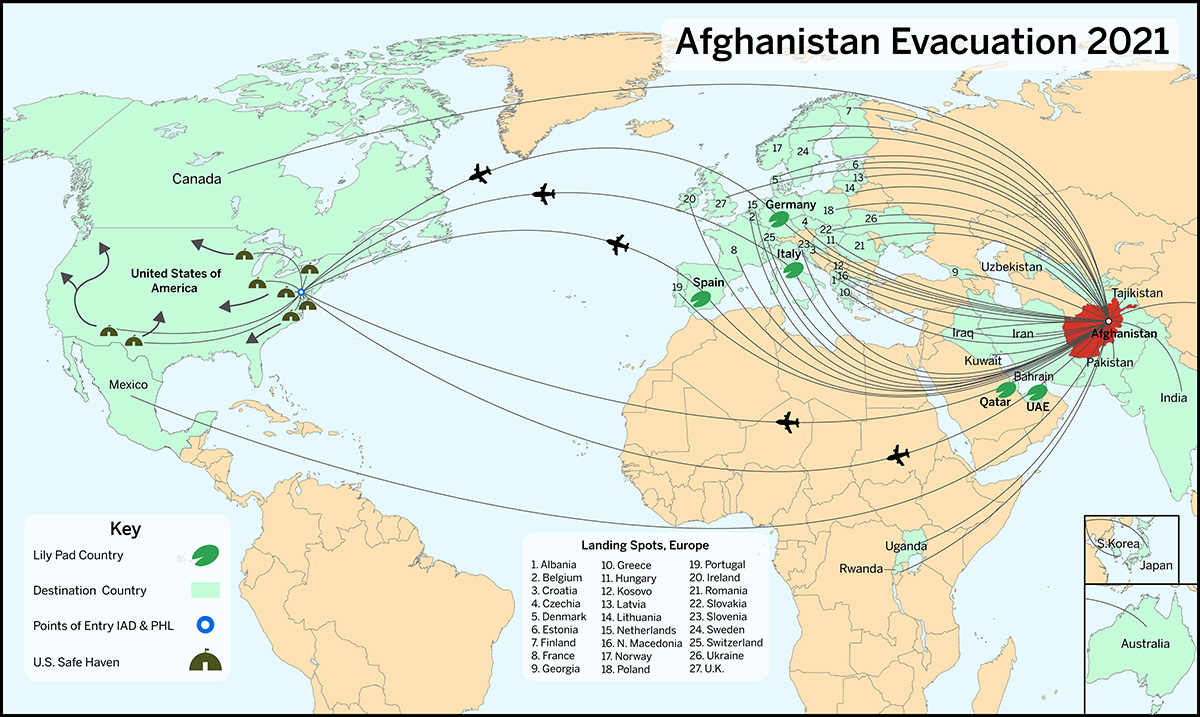

Note: This map is intended to show the movement of Afghan evacuees across the globe in the immediate aftermath of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. Destination Countries refer to countries that accepted any number of Afghan evacuees, and in which evacuees physically arrived in 2021. Data was compiled from numerous sources to generate a map that is illustrative but not necessarily definitive. Every effort has been made to obtain accurate information. For a higher resolution version of the map, please click here.

Chad Blevins / FSJ

The U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 and the evacuation, relocation and resettlement of allies is a defining moment in U.S. foreign policy. The events continue to elicit a great deal of commentary in the United States and elsewhere, much of it delivered without an appreciation of what was taking place on the ground.

We knew that members of the U.S. Foreign Service stood up to assist in the critical hour and played a vital role in evacuating more than 120,000 people from Afghanistan in the largest air evacuation ever and in an ongoing resettlement effort of unprecedented scale.

In early December, we invited members to share their experience working on any aspect of this crisis, including the successes as well as the adversity and tragedy. We received more than two dozen responses. We are so grateful to the authors for writing about their challenging, heart-wrenching work. They served on the task force in Washington, at the airport in Kabul, at the “lily pads” and other landing spots for evacuation flights, at the U.S. receiving airports (Dulles and Philadelphia), and at the U.S. military bases across the United States (the “safe havens”) housing the Afghan guests until they are resettled in American communities where they can start to build new lives.

Their essays—organized by the staging of the overall evacuation and resettlement effort—offer a unique inside look at the still-unfolding events. We also hear from an Afghan interpreter who describes his family’s journey from Kabul to Colorado in an article that follows the compilation.

Each of these individuals has written in a personal capacity, and the views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. government.

—Shawn Dorman, Editor

WASHINGTON, D.C.

A Race Against the Clock

Elizabeth Rood

A scene of the chaos around the HKIA gates. Taliban can be seen in white on top of the wall.

James DeHart

As the deadline for the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan approached in the summer of 2021, urgency increased for bringing to safety thousands of Afghan citizens who were at risk because of their work for or on behalf of the U.S. diplomatic and military mission over the past 20 years. The Biden administration faced a backlog of more than 17,000 Special Immigrant Visa applications, each representing lives to be saved.

On July 19, as districts across Afghanistan were falling to the Taliban’s military advance, we—the original Afghanistan Coordination Task Force—started our race against the clock. Led by Ambassador Tracey Jacobson and under the auspices of the State Department Executive Secretariat Operation Center’s Crisis Management and Strategy Office (S/ES-O), our “Operation Allies Refuge” team included members from the Department of State’s bureaus of South and Central Asian Affairs; Consular Affairs; Population, Refugees, and Migration; Administration; Global Public Affairs; Diplomatic Security; and the Center for Analytics. The team was joined by interagency partners from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the U.S. Customs and Immigration Service, NORTHCOM, CENTCOM, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the U.S. Public Health Service. Our tightly focused mission was to manifest SIV applicants and holders on charter flights and bring them to the United States for resettlement.

Reaching back to our home bureaus and agencies, the task force catalyzed innovations that will have lasting impact on how the State Department does business. We created a custom-built software application—“Hummingbird”—for gathering data about applicants, communicating with them, manifesting them for flights and tracking their progress from predeparture to resettlement.

To overcome limitations on U.S. Embassy Kabul consular services, we collaborated with Consular Affairs and CBP to use the first “foil-less” visas, allowing SIV applicants to be admitted as lawful permanent residents without a physical visa. We worked with Embassy Kabul to streamline panel medical exams and COVID-19 testing for a 24-hour turnaround. We implemented a brand-new legislative waiver of panel medical exams, allowing SIV applicants to fulfill this requirement upon arrival when exams were impossible.

The first SIV flight departed Kabul on July 29, only 10 days after ACTF’s formation; nine more flights followed by Aug. 15. Because we had the right team, an inspiring leader and a clear mission, we solved problems.

We worked with Embassy Kabul and Embassy Doha to surmount the obstacles our travelers faced along their journeys. Overcoming legal and bureaucratic challenges, we organized the transportation, reception and temporary residence of SIV applicants and their families at Fort Lee in Virginia, where they were adjusted to Special Immigrant status. Our PRM partners brought in the International Organization for Migration and resettlement agencies to counsel the arriving immigrants, connect them with resettlement benefits and transport them to their final destinations.

By Aug. 15, we had transported 1,962 Special Immigrants to the United States from Afghanistan. Having doubled the speed of our operations, we were on course to accelerate our tempo to two flights a day when the Taliban reached the gates of Kabul. Soon the Afghan government collapsed, U.S. forces deployed to secure and take control of Hamid Karzai International Airport, and the historic noncombatant evacuation operation began.

The original ACTF, which already contained the interagency components needed, became the launching pad for the immensely larger evacuation task force. We devoted ourselves with even greater energy to the crisis, forming the core of the new task force’s units. The technological tools, operating procedures and interagency relationships we created blazed the trail for the expanded enterprise that, by the end of the evacuation on Aug. 31, had moved more than 120,000 U.S. citizens, Afghans and third-country nationals to safety.

KABUL, AFGHANISTAN

The Apocalyptic Airport Scene

James P. DeHart

Conditions at Hamid Karzai International Airport during the evacuation in August 2021.

James DeHart

The flight out of Kabul at the end of the evacuation.

James DeHart

In Kabul, our challenge was getting the people we wanted into the airport. The scenes at the gates were apocalyptic. Getting to the front of the crowd, close enough to grab the attention of our Marines, took a full day of shoving through a mosh pit of roaming Taliban while gunfire rang overhead. The lucky few who made it arrived sunburned, bleeding, often in tears. Random young men who got inside were often tossed right back out. Our Marines hadn’t signed up for this sort of crowd control, but they adjusted to the task, as Marines always do.

A few meters back, our consular officers conducted a more thorough screening of the new arrivals and decided who could proceed to the C-17s. I was in awe of their stamina and their courage, working side by side with the Marines in this hellscape with so little between them and the suicide bombers we all knew might come soon.

There wasn’t much shelter from the sun, just whatever garbage people could string between the concrete barriers. Never had I seen so much plastic: water bottles by the millions, trampled and smooshed into one gigantic carpet.

The Marines had a whiteboard on which they scribbled the latest numbers at the airport. Our population was swelling uncontrollably. So we pushed hard for every seat on every outbound flight to be filled. I didn’t care who got on which plane, where they flew or how they landed. Those were other people’s problems. Let them sort it out elsewhere.

Calls and emails poured in. People didn’t understand why we couldn’t provide simple directions to at-risk Afghans on where to enter the airport. They couldn’t imagine what the gates were like—how dangerous it was for the people there and how catastrophic it would be for all of us if a gate was overrun.

We couldn’t bring in thousands of our citizens or embassy employees through the mobs, so we came up with alternatives. We organized careful movements to lesser-known gates and made sure we knew exactly who was showing up when. We kept them out of sight of the crowds and avoided creating any new mosh pits. Our Afghan employees did some impressive self-organizing and helped us help them. Through these orderly operations, we evacuated many thousands.

It was both the best and the worst thing I’d experienced in my career. The worst for obvious reasons, and the best because of my colleagues. It’s amazing what smart people can do when all the normal constraints are removed.

We improvised, and so did the Afghans. My former Afghan political adviser took his family and waded far down a sewage canal to enter at Abbey Gate, where our Marines pulled him in. Soon after, ISIS attacked us there. Thirteen U.S. service members were killed, along with many Afghans. It was just devastating, not least for our consular officers who had worked side by side with some of the same Marines.

We hunkered down for a while and then everyone said they wanted to get back out there. They wanted to get back to work. It was so humbling. Again, I was in awe.

When it was over and I was back in Washington, they asked me to lead the Afghanistan Task Force. Suddenly I cared who had gotten on which plane, where they had flown, and how they had landed. I was “elsewhere” now, and I had to help sort it out.

MED Docs Offer Support Through Chaos

Bob Y. Shim

The MED team deployed to Kabul for the evacuations. From left to right: Megan Ahearn (a U.S. consular officer); Christopher Casey (MP, U.S. Embassy Bishkek); Karl Field (MP, MED Foreign Programs); Bob Shim (RMO, U.S. Embassy Riyadh).

Courtesy of Bob Shim

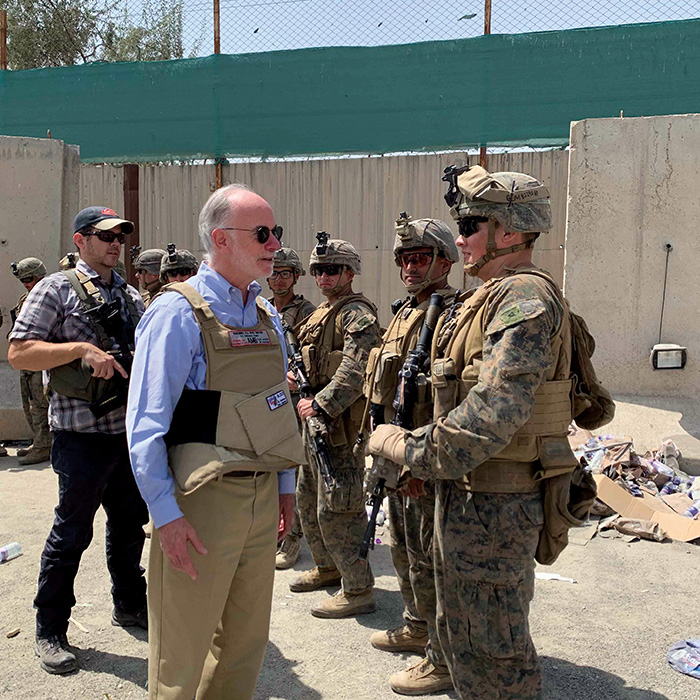

At Hamid Karzai International Airport, Ambassador Ross L. Wilson talks with the Marines at the gates.

Bob Shim

In the dawn hours, I arrived in Kabul on a C-17 with a Department of Defense medical team. My first impression was how quiet and serene everything seemed.

This illusion was shattered by the flood of scenes I witnessed during an initial tour of the Hamid Karzai International Airport (HKIA) perimeter with Ambassador Ross Wilson—thousands of people standing shoulder-to-shoulder, knee-deep in the sewage canal outside Abbey Gate, waiting for the slightest opening to enter; the road outside East Gate also knee-deep with hastily discarded clothing, children’s toys and other personal belongings; Marine medics treating the injured and those who passed out after days of standing outside in the heat; and the periodic bursts of gunfire and flashbangs in the distance.

Similar scenes played out daily for our small team from State’s Bureau of Medical Services (MED)—me and two medical providers—deployed to render assistance to our State Department colleagues. We quickly realized the extreme limitations of what the three of us with our portable kits could do in this austere setting, but we dove in, caring for Embassy Kabul personnel who were working around the clock.

We set up a small makeshift health unit at the Joint Command Center and supported consular teams on excursions to the gates to screen potential visa recipients. Looking back, providing care for the State Department staff—even when reduced to treating minor injuries and intestinal upset—helped alleviate stress and increase morale in intangible ways and support the overall mission.

Though we had initially anticipated some sort of humanitarian component to our mission, our resources were very limited. As it happened, the impact of our support to State personnel was much more significant than anything we could have remotely achieved attempting to provide care for evacuees.

Some memories from the chaos I will not soon forget. The first is assisting a Kabul Health Unit locally employed staff doctor and his family who were stuck outside the airport gates. After they had been unable to find a way into the airport for days and had been held for hours by the Taliban following the bombing, we helped them board an evacuation flight only two days before the operation concluded.

I met this family again at the Doha evacuation center to see them onward to Dulles International Airport, where they were connected with MED’s principal deputy chief medical officer, Dr. Rick Otto, who guided them to their destination in California. They were also gifted travel money personally from our regional medical manager. I have never been so proud to be a part of the MED family.

I also recall one moment during an interaction between a consular officer and an evacuee when the officer broke down in tears at the plight of many Afghan families having to be separated. My deep respect goes to these brave officers who served tirelessly at the HKIA perimeter gates under impossibly stressful conditions to process potential evacuees. They did so with the utmost compassion, care and professionalism. These heroes of this unprecedented operation must not be overlooked.

Many have asked about my brief deployment to Kabul during the evacuations, and the most fitting description of the experience is that it was chaotic, surreal, tragic and inspiring—all at the same time. Nevertheless, the single, enduring memory will be the people—both Afghans and non-Afghans—who gave the best of themselves on both sides of the perimeter walls at HKIA during those heart-wrenching weeks in August.

And Then, We Went Back to Work

Jayne Howell

At Hamid Karzai International Airport, a view through the East Gate where belongings were discarded.

Bob Shim

Near the gates at Hamid Karzai International Airport consular officers conduct interviews with Afghans seeking to leave, a difficult and often heart-wrenching task.

Bob Shim

I’ve served in Afghanistan twice. First, in the heady, optimism-filled days of 2004 when we moved easily around Kabul in thin-skinned vehicles, our body armor growing dusty as we were welcomed into Afghan homes and weddings as liberators and partners. I toured tiled mosques and reopened museums. I got to know Afghan families over fragrant platters of qabuli palau and cups of green tea with sugared almonds. I attended Sufi concerts in antique rose gardens, learned to bargain for rugs on Chicken Street. I toured the ancient citadel of Ghazni, walked in the footsteps of Rumi in his birthplace of Balkh, and hiked along the base of the bombed-out Buddhas in Bamiyan. As an observer in the 2004 election, I cried as euphoric women cast votes, many of them literally shaking with the weight and privilege of having a voice.

I returned to a very different Afghanistan in 2011. Our military presence and civilian surge were at their peak, and so, too, the insurgency and violence. The ambassador began our country team meeting each week by reading the names of military servicemen and women who had been killed since the last meeting. In 52 of those meetings, only one passed without that terrible marker. For each one of those names, there were hundreds of Afghans who also lost their lives, and we held space for them all.

When Kabul fell and the department was seeking volunteers to assist with an evacuation, I went. I thought I could contribute; but, maybe selfishly, I also wanted to be there knowing no more American names would have to be read, no more ramp ceremonies honoring the fallen, no more young lives would be lost so far from home. Only that wasn’t the way it happened.

On Aug. 26, just before our shift change at 6 p.m., I walked out of a planning meeting into the normally bustling Joint Operations Command Center we shared with the Marine Corps leadership. I expected to hear the usual hum as colleagues greeted each other, exchanged notes on the day’s events and maybe even joked a little. Instead, I opened the door into a stony, deafening silence.

My colleague was waiting for me—“A bomb, Jayne, at Abbey Gate,” she said. In that silent JOCC, surrounded by the Marines desperately waiting to learn the fate of their comrades, we waited. And when the news came—13 Americans lost, and hundreds of our Afghan partners killed and injured—it was so much more horrific than I could have imagined.

We were so close, so very close to No More Names.

Instead, it was one of the deadliest days for America in the 20 years of conflict. And then, just a few moments later, a Marine quietly asked me if the consular officers were ready to go back to work. I consulted our Diplomatic Security colleagues, and then I asked for volunteers. I didn’t see a single person without a hand up. And so, we went back to work.

The following day, we all lined up on the tarmac for the ramp ceremony to bear witness as our fallen colleagues boarded their final flight home, their hero flight. I will never forget what it felt like to stand there in the midday Kabul sun, hands clasped and shoulder-to-shoulder with my State Department colleagues and military brethren for that awful, beautiful, heartbreaking ceremony.

Time stopped as their coffins, one by one, passed us slowly on the shoulders of their friends and comrades. The last ramp ceremony in Kabul. And then, forever changed, we went back to work.

Consular Officers on the Line in Kabul

Jean Akers

Consular team leaders Jayne Howell (at left) and Jean Akers (at right) at Hamid Karzai International Airport early on the morning of Aug. 30, 2021.

Conn Schraeder

I left Kabul on Aug. 30, 2021, alongside 20 other U.S. diplomats and 300 Marines jammed into a C-17. Two hours earlier, I had crouched under a desk as C-RAMs intercepted incoming rocket fire. Now, as we lifted off, I was sleep-deprived, emotionally raw and tremendously proud of all we had accomplished. I lamented that we couldn’t do more. I still do.

For 11 days and nights in late August, I helped lead the consular team on the ground. Our team’s primary role was to determine whether people who made it to Hamid Karzai International Airport met the criteria—as defined by the White House and State Department leadership—for evacuation on a U.S. flight. We didn’t have access to systems or databases, but we did have the good judgment and decision-making skills consular officers exercise every day around the world.

Each shift change, either I or my co–team leader briefed the team before they headed out for 12 hours to interview prospective evacuees in the heat or the dark, wearing full PPE, accompanied by heavily armed security personnel and Marines. We repeated certain phrases each time: “We trust your judgment. We support you. Ask for help when you need it.” And always: “Remember: every life matters.” Thinking of the thousands massed outside the airport led to despair. We stayed grounded by focusing on each individual.

Touring the perimeter of the airport with the U.S. Embassy Kabul consul general, August 2021.

Bob Shim

From the command center, we passed information to our officers on specific cases we were tracking—such as unaccompanied minors, infants with medical needs or other especially vulnerable Afghans—and updated senior leadership on progress or roadblocks. Every couple of hours we checked “the board” for the latest evacuation numbers to update the task force.

We collaborated with military partners to solve all manner of problems: everything from “How do we get more Americans out?” to “How did this random plane from country X just land without anyone knowing?” Calls, texts and emails from NGOs, congressional staffers, colleagues, friends and total strangers poured in, begging for help for this person or that group. Sometimes our team could help get someone onto the compound; other times they made it through on their own. Each success warranted a high five, or a “yay, team!” on our group chat. Other times, we couldn’t make it happen. Each of those still haunts me.

The night of the Abbey Gate bombing, we hunkered down. I texted the team: “Tell your family you’re safe.” Some of them thanked me, later—in the shock of the moment, they hadn’t thought to reassure loved ones. A senior military officer addressed his team at the command center; his words gave me strength. “This is a tragedy,” he said, and paused. “We do need to mourn, and that time will come. But how we honor them right now is by carrying out our mission.”

Two hours after the bombing, flight operations resumed. We went back to work.

The Last Consular Officers at the Gate

Arleen Grace R. Genuino

A consular officer reviews documents at HKIA, August 2021.

Bob Shim

The last flag standing. The United States was the last coalition partner to leave the Hamid Karzai International Airport in August 2021.

Arleen Grace R. Genuino

Kabul. Time’s up. After arriving at post end of July began a rapid succession of deadlines that passed, and all of us at the embassy had to quickly shift and move on from one to the next. Overlap with my predecessor ended. Time’s up.

About four days after that, we were in the midst of hurried final destruction sessions, shredding or destroying anything with contacts or our personal names or the embassy printed on it (yes, it felt just like that opening scene of Embassy Saigon in “Argo”). Time’s up.

A day and a half later, we boarded helicopters fully armored, saw the embassy for the last time and headed for Hamid Karzai International Airport. Time’s up again.

Days took on a strange routine as we trudged all over that garbage-strewn airport. The security situation was tenuous those first days at HKIA. Afghans breaching the airport’s security perimeters prompted our tense sheltering in place.

Despite those moments, many of us were determined to stay until our embassy’s locally employed staff and their families could depart, and passed up leadership’s offers to evacuate further to safety. Thank God for our military!

With security improved, dozens of us began 12-hour day and night shifts to screen Afghans desperately trying to evacuate at HKIA’s entry points. Everyone dusted off their consular titles. Consular reinforcements also arrived from other posts and from Washington, D.C. I split my time on shift between screening Afghans and working on protection issues. We got strangely used to hearing and seeing tracer fire light up the night sky.

The suicide attack at Abbey Gate on Aug. 26 that claimed so many U.S. and Afghan lives reminded us how real the danger remained. I thought of my father who worked as a U.S. government third-country national in Vietnam during the 1968 Tet Offensive. Now, here I was, his daughter, carrying on a similar service legacy more than 50 years later.

Our time on the ground was limited; the end date would shift but was nearing. So many people were still outside the gates desperately hoping to get inside. Feelings of powerlessness grew among us as more gates closed for security reasons. Friends, colleagues and strangers with any distant Afghanistan nexus found us via email and pleaded for help getting in, and we tried desperately to offer what little help we could when possible while still working our shifts.

A small group of us were asked to be the last consular officers on the ground and to push through to fill the last flights with little sleep on Aug. 29 and 30. Sheltering because of one last rocket attack on the airport a few hours before boarding our own outbound C-17 was a surreal ending to our time at HKIA.

Foreign Service and Civil Service officers worked alongside our military to look out for the most vulnerable in the airport crowds. That fact is sorely overlooked by media coverage. Our military were handed children at the gates by their parents in hopes of saving them. Foreign Service and Civil Service officers had the more onerous and longer-term task that continues even now to attempt reunification of these youngest evacuees, first at HKIA or at a subsequent processing point outside Afghanistan. The United States has taken in approximately 1,300 Afghan unaccompanied minors since August.

Our time at HKIA may have finished, but our evacuation efforts did not end on Aug. 30. Many HKIA alumni and additional department staff continue today to serve valiantly at our Doha lily pad in Qatar, in both temporary duty assignments and as part of our evolving Afghanistan Affairs Unit presence post. The State Department deserves due recognition for the heroism displayed by its own ranks.

LILY PADS

The Evacuation Is On

DOHA, QATAR

Mark Padgett

Exhausted Department of State personnel and U.S. Marines begin their ride home via Kuwait City on a C-17 on Aug. 30, 2021.

Arleen Grace R. Genuino

On Aug. 15, 2021, one of the first flights of Afghan evacuees arrived at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. This iconic photo shows the Air Force C-17, with a rated capacity of 250, packed with no fewer than 823 people.

U.S. Air Force

“We have a C-17 inbound in 30 minutes with approximately 400 Afghan nationals that rushed the plane in Kabul. Intentions unknown. Hijacking possible.” My jaw dropped. It was around 2:30 a.m. on Aug. 15 when an Air Force officer had tapped my shoulder, asking, “Are you State?” and said I had a phone call from Brigadier General Gerald Donohue, the 379th Wing Commander at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

The night had begun innocuously enough when our economic officer, Nikhil Lakhanpal, and I volunteered to relieve some co-workers who had been at the air base the previous day shepherding embassy employees and third-country national contractors out of Kabul through Qatar.

I had only been in Doha for a little over a week and wanted to do my part. We expected a boring night of verifying manifests, checking Excel spreadsheets and greeting weary colleagues. The first sign of things to come was when a plane landed around 2 a.m. that, disconcertingly, had an Afghan family of six among the contractors and staff.

For about 15 minutes, Nikhil and I scrambled, reaching out to Ops, Consular Affairs in Washington and anyone who could help figure out what to do about this family—these initial six evacuees, the harbingers for the more than 123,000 people who would follow in the coming weeks.

Heart-wrenchingly, they immediately asked to go back to Afghanistan because they were worried about parents and siblings who had been separated at a Taliban checkpoint. After explaining that that was impossible, we managed to get them some cots and settled them in a tent near the in-processing terminal by the tarmac. Just as I was starting to feel like I had things under control, I got that tap on the shoulder.

They say that in crisis, things become a blur; but it’s the opposite. I learned from combat experiences in Iraq that things slow down, and the brain becomes transfixed, like tunnel vision. I remember what happened next with absolute clarity. I called the chief of mission to tell him about the inbound flight, and suggested to the military that they wait and see what the passengers’ intentions were before rushing to conclusions.

Sure enough, once it landed, the C-17 was half-filled with women and children. A few had luggage; most had nothing. One man was wearing only one shoe. A pregnant woman’s water broke. The looks of terror and exhaustion in their faces were visceral. We greeted them as best we could, emptying out a large bay that quickly filled up, and handing out MREs (meals, ready-to-eat) and water amid the crush and smells of hundreds of people packed together. By 5 a.m., the scorching 120-degree, 100 percent humidity Qatari heat loomed. Because the bay couldn’t fit everyone, we decided to have a dozen transport buses come down to the tarmac and loaded them up. It wasn’t comfortable, but at least there was air conditioning.

I did a rough count and estimated there were around 640 people. A colonel told me I was crazy—“C-17s can only hold 250 people max.” Turns out we both were wrong; there were actually 823 passengers (as captured in the infamous photo of the packed cargo hold, above). By 6 a.m., embassy leadership had arrived, and Nikhil and I were able to step back, shaken.

But the respite was brief. For the next 17 days, I would be co–site lead at nearby Camp As Sayliyah, where at any moment 8,000 evacuees were housed in facilities built to accommodate 2,500. But that is a whole different story, with its own heartbreaking and uplifting moments that will both haunt me and fill me with pride for the rest of my life.

In Limbo in Abu Dhabi

EMIRATI HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE CENTER, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Cynthia Segura

Evacuees finally board a flight out of Kabul.

Bob Shim

“And how many bags do you have?” I asked the patriarch of a family of nine. The translator conveyed the answer: “One.” I handed him the luggage tag and wished them a safe trip. Silently I hoped that their one suitcase contained nine jackets for their arrival in Philadelphia. Like so many of the families fleeing Afghanistan, they barely escaped with the clothes on their back. These were the lucky ones, traveling to a new life in the United States.

In October I had the opportunity to work in Abu Dhabi at the Emirati Humanitarian Assistance Center, or EHC. The experience provided me insight into the plight of the Afghan people and the complexities of the largest airlift in history.

The EHC’s role is unique in the Afghanistan evacuation in that evacuees are not hosted at a U.S. military base nor under the care and control of the U.S. government; they are guests of the Emirati government and housed in apartment buildings with all their basic needs provided. They are not allowed to leave, except for medical care, until they depart for relocation. Some evacuees have been there for more than 75 days, and counting. Some have a clear path to the United States; but for many, the onward path is less certain.

In my three weeks there, we processed nearly a thousand evacuees for travel to the United States. As one of the final steps in their journey, we verified their identity, measles vaccination status and negative COVID-19 test, and ensured that no minors were left behind. Every person boarding that plane felt like a huge victory, the culmination of a massive interagency support effort plucking them out of Afghanistan to the relative safety of the United States.

For every person who made it onto a plane, approximately 10 others have no clear way out and no mechanism to stay. While many of these evacuees are legitimately fleeing religious persecution, without a visa in hand they are unable to travel to the United States or any other country. The concept of asylum does not exist in UAE law, nor does the UAE recognize those escaping war or persecution as refugees.

There are many logistical challenges with processing some of these people. Many arrive with no national identity card nor any way to verify who they are. Things we take for granted, such as birth dates and last names, are more fluid in Afghanistan. Should we take on the risk of welcoming these evacuees? If we do, what are their chances of assimilating? What will happen to them if there is no path out?

In parallel, humanitarian organizations continue to bring more refugees into UAE through privately funded flights, and the population of souls in limbo continues to grow. What becomes clear to me in my short time is that though we have left Afghanistan, our complex entanglement endures.

Attention to Mental Health Aftereffects

KUWAIT CITY, KUWAIT

Karen Travers

Representatives from State, the U.S. Army and the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration huddle together to discuss the next day’s evacuation efforts at HKIA, August 2021.

Marjon Kamrani

In late August and early September, I watched along with the rest of the world as the U.S. performed the monumental task of the Afghanistan evacuation. I would have gone to Afghanistan if asked, but mental health care is better provided on the tail end of any crisis, when the adrenaline has stopped flowing and people have a chance to sit and reflect on what they have just experienced.

The second week of September I traveled to Embassy Kuwait to help manage the potential mental health sequelae of the mission staff who had been involved in housing, feeding, clothing and caring for more than 5,000 Afghans and nearly 1,000 Americans and third-country nationals transiting through Kuwait. Because the Kuwaiti government only allowed evacuees to stay for 14 days, the Embassy Kuwait team and their Department of Defense partners had two weeks of incredibly intense around-the-clock activity, which ended abruptly when the last evacuee boarded a plane on day 14.

By the time I arrived, the evacuees were gone, and leadership’s focus shifted to managing the potential aftereffects on the embassy staff. I spent a week in Kuwait, and while my door was open to anyone who might need to talk about the experience, the most important work happened behind the scenes.

As I usually do during a regional visit, I scheduled “consultations” with most of the section heads, as well as the front office, so that I could understand how their folks were doing post-evacuation. To a person, the section heads were incredibly proud of the work their teams had done and the positive impact they had had on the lives of the Afghans. Each leader did a fantastic job of taking care of staff and was able to tell me who had fared well and who might need a little more attention.

What surprised me most about the hour I spent with each was how therapeutic that time was for the senior FSOs themselves. They had stepped up in a crisis and performed exceptionally well. They had all thrown themselves into the situation and successfully guided their teams through the evacuation. All knew their sections had made a huge difference.

Few of the embassy leaders, however, recognized that they themselves might need some mental health counseling—or at minimum, a chance to talk about what they had experienced and what had bothered them over the previous two weeks. In essence, my one-hour visit with each was a mini mental health house call.

I asked questions that all mental health providers ask: How were they doing? Were they sleeping? Eating? Engaging in self-care? I encouraged each to model a healthy work-life balance in the aftermath of the evacuation.

We often talk about second- and third-order effects of decisions made by those in the chain of command. In this case, I had the distinct pleasure of caring for the second- and third-order FSOs—the leaders who cared for their people, who cared for the evacuees.

I’m not sure any of these embassy team leaders recognized that they had participated in a mental health appointment—I hope I was far more subtle than that. But, by leveraging the typical consultation and bringing my expertise to their offices, I provided the supportive therapy that each needed in a confidential, comfortable environment.

From Al Udeid Air Base to Kentucky

AL UDEID AIR BASE, QATAR

Marjon Kamrani

An Afghan evacuee (far left) and the author (to his immediate left) celebrate Thanksgiving with her family in Nashville, Tennessee.

Marjon Kamrani

In mid-August, around 1 a.m., I met an Afghan evacuee for the first time, standing outside a former U.S. military installation in Doha, probably the hottest place on earth at the time. I had volunteered to relieve my beleaguered U.S. Embassy Doha colleagues, many of whom had spent several sleepless nights assisting U.S. contractors as they pit-stopped in Doha on their way out of Kabul. I expected to spend a day or so with some tired Americans, help procure food, hopefully inspire a laugh and get folks to their families.

That all changed when I arrived at Al Udeid Air Base with the embassy Treasury Department attaché, who had responded to the same volunteer request. On arrival, we received word that a few hundred Afghans had unexpectedly landed the night before. Our recently closed Army installation down the road would suffice for their stay, so we headed there. We prepared for what we thought would be around 600 evacuees. There were more, around 8,000 at one point. There are many I will never forget—the pregnant Afghan air force pilot, the 5-year-old unaccompanied minor, the man carrying a suitcase full of his diplomas but nothing else.

Over about a month, save a day or two here or there, I learned nearly every nook and cranny at the base. I worked closely with my political-military colleague, who had arrived in Doha for his assignment only one week prior to the evacuation. We did what midlevel State department officers could in an environment with little guidance, no computers and only a few other State Department staff (until thick-skinned and gold-hearted TDY [temporary duty] colleagues showed up).

We handed out water with our fearless military colleagues, tried to relieve scared Americans, organized legal permanent resident families and visa holders who could fly immediately to the United States, and calmed traumatized people who had left family behind. We talked evacuees down from walking off the base, a sure way to upset the host government. State and Army colleagues spent nights huddled together making plans for the following days—plans that would unfold in messy and confusing ways—but we managed to move hundreds of evacuees off the base almost daily. We also spent time commiserating, bragging about how much weight we lost (at least five pounds on average) and who had found the cleanest bathroom available.

I left the effort in early September. Efforts continue but not nearly to the same degree, and now it’s more orderly. At least a hundred evacuees have my phone number. I could always change my number, or not respond to the texts.

It’s still hard. That’s what I hear from one young Afghan evacuee who helped me with translation. He’s a former NGO human rights worker now in Bowling Green, Kentucky, a one-hour drive from my hometown, Nashville, where he spent Thanksgiving with my family. He’s there with around 200 other Afghan evacuees. He just received his Social Security card, and he’s thinking of applying to Western Kentucky University. He translates for other Afghans and helps them navigate a system that he’s also learning to navigate.

The children in Bowling Green just enrolled in school, but there is little by way of an immigrant community to support the new arrivals. I hear one family has already experienced a nearly fatal gas leak in their run-down apartment. Their hard part isn’t over. Their happy ending is hopefully unfolding. It’s complicated, tragic, inspiring all at once. I’m forever part of it. I’m proud of that. I’m not erasing those phone numbers.

The Sheer Humanity of It All

AL UDEID AIR BASE, QATAR

David Lawler

When I first stepped into the WRM, the reality of what we were trying to accomplish hit me hard. This is what evacuating tens of thousands of people from Afghanistan feels like, and it’s oppressive.

The WRM, or War Ready Materials, is a warehouse on the Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar where evacuees were held pending an onward flight. The key term is “warehouse.” The WRM was never designed to hold people; it was designed to shield military equipment from the punishing Qatari sun. That means it’s just a hollow shell of a building with no overhead fans, no running water and, most importantly for Qatar in August, no air conditioning.

I wasn’t there from the beginning, though, when extreme conditions in the warehouse were making headlines around the world. By the time I arrived, the military had already begun cutting holes in the walls to connect industrial-sized A/C units. But still, the building is so massive that if you stood 30 feet away from one of the new vents, you felt no cooling breeze. You only felt the hot, stagnant air and ubiquitous dust.

Now take those life-sapping conditions and add a few thousand people. It was physically uncomfortable. It was mentally exhausting. It was overwhelming in so many ways.

But on the other side of that discomfort was the pure humanity of it all. Hundreds of U.S. military personnel were volunteering on their days off to work in the WRM handing out food, water and clothing to the evacuees, or just kicking a ball around with a group of kids.

Colleagues from State and USAID worked to solve problems where we could, whether it was the old man who simply wanted a clean shirt, or the worried husband wanting to know if his wife had given birth yet and if the baby was healthy. There weren’t many other ways we could help, but we tried.

Then there were the evacuees themselves. They had risked their lives to flee Afghanistan and were facing an uncertain future. They had just lost everything, literally everything. And yet a short man in his mid-30s approached me one day to ask if I needed help. Me?! I was the one who got to slink back to a five-star hotel in Doha every night and stand under the shower for 20 minutes. How could he possibly be so selfless? But that’s who they were. The equanimity they showed in the face of such a hopeless situation was humbling.

There was the bodybuilder who was an absolute beast of a man. He made jewelry back home and cried when he told me about his children. There was the young woman whose family lives in Woodbridge, Virginia, so close to me. I still regret not giving her my number so she could let me know they made it home.

And then there was the famous Afghan singer who was now an evacuee like everyone else. One evening he co-opted our ad hoc PA system to sing songs and raise spirits, and in a small piece of magic, there was dancing.

I could not begin to understand what had just happened to all these people. But the patience and grace shown by the Afghans who made it through the WRM will forever make them, at least in my mind, the best ambassadors of the Afghan people.

Inside the Holding Facility

ABU DHABI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Ravi Kaneriya

“Yet love can move people to act in unexpected ways and move them to overcome the most daunting obstacles with startling heroism,” wrote the Afghan author Khaled Hosseini in his novel A Thousand Splendid Suns.

I couldn’t help but reflect on this quote when I thought about my early experiences at Abu Dhabi International Airport, working on the front lines, processing the very first flight of Afghan evacuees who arrived in the United Arab Emirates after fleeing Afghanistan. I was struck by the spirit of the Afghans I met, who, facing harrowing experiences and overwhelming obstacles, managed to arrive in the UAE, exhausted and anxious about the future, and yet composed and polite despite everything they had been through.

I saw children, some crying, but also some smiling and curious as I met them—reminding me of the innocence of children, unaware of the dangers they had fled or the uncertain future before them. And I was also struck by the love, commitment, courage and sheer determination of parents, who had overcome impossible odds to bring their entire family, sometimes up to a dozen children, through the collapse of a country and in search of a better life.

Later, working with our control room, I received the information of thousands of Afghan evacuees at a UAE holding facility, awaiting a coveted flight to the U.S. As I read their submissions one by one, I came to learn so much about the stories of individual people—the Afghan comedian and talk show host, senior Afghan military leaders, human rights activists, civil servants, teachers, athletes, entrepreneurs and people of every background, socioeconomic class and life experience.

I couldn’t help but feel that inside that UAE holding facility, there were so many talented, driven and decent people who wanted to be part of American society and had so much to offer. It’s true that not everyone in that camp followed the normal procedures for immigrating to the U.S., but the circumstances of their departures from Afghanistan were hardly normal.

As Khaled Hosseini wrote in his other book The Kite Runner: “It may be unfair, but what happens in a few days, sometimes even in a single day, can change the course of a whole lifetime.” There are future American scientists, businesspeople, lawmakers, artists and even diplomats inside that holding facility in the UAE right now, if only we are ready to act with compassion, flexibility and pragmatism to embrace the huddled masses there, yearning to breathe free.

Vetting Evacuees and Addressing Burnout

AL UDEID AIR BASE, QATAR

Paul S. Dever

Early in the “Kabul Situation,” I volunteered to go to the Afghan capital to assist in the embassy shutdown and evacuation. I had served before at the embassy (2006-2007, and again 2014-2016) and was familiar with the mission and staff. For operational reasons, however, I was detoured to Doha, to assist in evacuee processing. I arrived there on Sept. 24 and began work the same day.

Initially, I was assigned to the Al Udeid Air Base hangars where evacuees were being processed, where I liaised with agents from the Department of Homeland Security, Customs and Border Patrol, the Transportation Security Administration and the FBI to ensure citizenship verification, and proper vetting and classifications for the manifests.

I joined the throngs of people, seeking out American citizens to ensure that they were processed expeditiously and to explain how delays could occur if they stayed with their “blended” families. I left the choice entirely up to them; after all, family is family. I ensured that the Afghan evacuees were properly informed and could make their best decisions. Identifying at-risk persons, due to single parentage or disabilities, I facilitated their integration and feeding to ensure their stays were as comfortable as possible.

I soon transferred to the management team in the personnel center provided to State by DoD at the airport. I took on more responsibility, continuing the interagency collaboration in seeking data points for the four-times-daily “lily pad” reports required by the White House and others. Identifying a need to have “eyes on” non-base personnel at all times, I liaised with the flight teams to ensure an orderly procession of passengers headed onward to Europe or the U.S.

The display of compassion and safety were recognized and appreciated by both passengers and team members. I also worked with the IT team at Embassy Doha to provide greater infrastructure and equipment to ameliorate data collection and transfer.

Recognizing that burnout could become a problem, I volunteered to provide relief trips to other staff to ensure they got proper midshift rest and sustenance. Whether by transporting people to food and food to people, or ensuring people rotated through the air-conditioned office with refreshments, I ensured a lifeline that managed to keep teams fed, rested and ready to work.

BORDER/TRANSIT COUNTRIES

Little Afghan Refugee

TASHKENT, UZBEKISTAN

Azam Abidov

A little Afghan refugee

Sleeps

in the very crowded plane

She knows nothing about

where they are heading

It does not matter:

Her mother is with her.

She is not afraid anymore

of the AKs or war

That made her heart hard

Very hard.

Still there is a tiny place in it

For love and light.

The little Afghan angel

Sleeps in the very crowded

Military plane.

The only thing she sees

in her dream is—

Air.

A Last Heroic Act by Afghan Pilots

TERMEZ, UZBEKISTAN

Sandra Jacobs

Sandra Jacobs (center) with members of U.S. Embassy Tashkent’s “Team Termez” at the airport in Termez, Uzbekistan.

Uktirbek Tadjimov

In the chaos of Aug. 15, approximately 500 U.S.-trained Afghan pilots and other personnel fled over the northern border into Termez, Uzbekistan, aboard 46 Afghan military airplanes and helicopters. For the Afghans, this was one last act in service of their partnership with the United States: They left their families behind to prevent the aircraft from falling into Taliban hands.

Their arrival kicked off an intensive, monthlong diplomatic process that led to securing non-refoulement commitments from the Government of Uzbekistan, ensuring safe lodging in a temporary residential camp, making contact with the pilots and other personnel, collecting biometric data for the entire group and, ultimately, manifesting and checking in our Afghan allies on three charter airplanes out of Uzbekistan.

As a part of the embassy’s interagency team led by Political-Economic Chief Matt Habinowski, I joined my U.S. diplomatic and military colleagues in Termez for an intense final push to relocate these vulnerable allies to a safe location. From the check-in at the camp to a final wave as they boarded the charter Uzbekistan Airways flight to the United Arab Emirates, our Afghan allies demonstrated courage, dedication and commitment to service.

One pilot had a bullet lodged in his back. Another suffered a back injury when he was forced to eject from his A-29 Super Tucano. Among this crowd of Afghan men, our embassy team took special care of one former Afghan military officer who had escaped with his wife and three small children. Their presence was a heart-wrenching reminder to the other men of the families they were forced to leave behind as they followed orders to evacuate the aircraft out of Afghanistan on Aug. 15. Our embassy team worried that the family’s presence might tempt others to give up on relocation and return to Afghanistan, but in the end every man boarded the plane—retaining hopes of eventually being reunited with family and building a better life in the United States.

This autumn’s events join a few extraordinary moments in my Foreign Service career, when I was truly overwhelmed by the commitment to service demonstrated by my colleagues. All of us from Embassy Tashkent’s “Team Termez” felt a powerful connection to similar efforts happening in other countries bordering Afghanistan, at “lily pads” in Northeast Asia and Europe, and at Afghan reception centers in Dulles and beyond.

Coming together to execute such a complicated, politically sensitive operation demonstrated the creativity and determination of those in service to the U.S. government. For all of us, it was a huge relief to learn the group had finally landed in the United States. We remain hopeful their families will find a way to join them in the very near future.

Saving Afghan Pilots’ Families

TASHKENT, UZBEKISTAN

Alexis Sullivan

Afghan pilots await departure from residential camp in Termez, Uzbekistan, August 2021.

Sandra Jacobs

“Team Termez” checks in Afghan Air Force for relocation flight out of Uzbekistan.

Matt Habinowski

It was the most momentous call of my career. Who else could we get out? I knew there was a safe way to get people to Kabul airport, but could they get there in time?

So while our primary responsibility in Tashkent remained responding to Americans and other priority groups transiting Uzbekistan, as acting deputy chief of mission I asked our country team who else on our collective radar remained in Kabul for whom we should make a referral in the U.S. national interest.

After a drop by and a few failed calls because I forgot the right way to dial the Defense Switch Network, the right people put me in touch with the right person at the right time. Turns out, there were brave Afghan airmen and women along with their families who had stayed behind in Kabul so other members of the unit could save the lethal equipment—and the well-trained operators—from falling into the hands of the Taliban or even worse.

But when I had picked up the phone, I had no sense of what was at stake. There were just two packets of details and faces of an airman's family members, sent out-of-protocol amid a sea of increasingly desperate and out-of-protocol emails that would only increase as the days went on.

My question to start was: “Are there more such families in Kabul?”

“Yes.”

“Wait, there’s still high-ranking airmen left in Kabul?”

“Absolutely.”

They were heroes who stayed behind on the tarmac in Kabul with the hopes of rescues for the rest of the unit and all the families, but also to lead the group to safety in the middle of the night and provide instructions. The families knew their loved ones were doing one last mission for their country and their people. On that call, our small team realized we could give them a fighting chance in Kabul.

But there was a problem. We couldn’t just send a group of document packets by email down to Kabul and say, “Here’s a bunch of folks to rescue; good luck with that.” So I said to the colonel, my rank equivalent in the DoD: “We’re going to have to rank order them.”

Silence.

Me again, informed by my two tours in State Ops and countless hours working task forces: “Kabul needs to be spoon-fed; we have to rank order these packets so they know who to go for first.”

“Yes, OK.”

Temperature check to my team, who had stayed in the room with me without asking, only because they knew they should. We all agreed.

“OK,” I said to the team. “Who’s out first?”

With clear eyes and a full heart knowing the importance of getting this right for the U.S. government and the lives of this particularly in-danger group, I am proud that our efforts saved Afghan heroes who have been mentors and role models to hundreds of Afghan and U.S. airmen in the last 20 years. I hope to be able to shake their hands one day and see how all the babies in photos from the email packets continue smiling as they grow up in peace.

U.S. LANDING POINTS/PHILADELPHIA & DULLES

Bravery in the Face of Tragedy

DULLES EXPO CENTER, VIRGINIA

Mike Junge

Afghan Air Force evacuees wave farewell to Embassy Tashkent staff at Termez Airport, Uzbekistan, in August 2021.

Uktirbek Tadjimov

In one capacity or another as a contracting officer, I was with the USAID/Afghanistan mission for 4 1/2 years (2006-2010). When the call came for volunteers, which just so happened to coincide with my leave in the United States, there was no question that I would step up.

I take away many impressions, but first and foremost is the resilience of the Afghan people. Bone-weary and facing an unknown future, and with great stress written on their faces, they were also quick to smile and give a heartfelt thank you for even the smallest of gestures (e.g., a candy or toy for their children, an offer to carry their bags, assistance in directing them to the correct location).

My other impression is just the massive scale of the operation at the Dulles International Airport location. Every time I arrived at the “Dulles Center” (the special section at Dulles airport), it was impressive to see the complicated logistical aspects of the operation. As an outsider looking in, you would never know of the logistics in moving so many people, particularly during a pandemic. But it was highly complex, because essentially overnight, the U.S. government set up brand-new airlines with all the complications of passport control, COVID-19 testing, ticketing and baggage handling. For most of us, it was a career in which we had no prior experience.

During my time volunteering at the center, there were stories of great tragedy and lives uprooted, but equally there was example after example of resilience and a determination to put forward a brave face—which I can only imagine took incredible resolve. I am honored to have been able to volunteer. To the Afghans we were able to resettle, I wish you great success in your new country. Yet, we also need to remember that our job is not done; hundreds more in Afghanistan still need our assistance.

A Dulles Landing and a New Wristband

DULLES EXPO CENTER, VIRGINIA

Danielle Spinard

I volunteered at the Dulles Expo Center as part of an amazing team helping to “intake” hundreds of Afghan refugees. Of the many, many Afghans we processed, one stands out for me.

I remember clearly the exhausted face of a mother traveling alone with her two children. On their arms were stacked different colored wristbands. They held out their arms while we cut the old ones off and then added a new one. The wristbands were a sign of each transition and “check-in” this family had made on their way out of Afghanistan.

I tried to make this wristband different, so I scribbled a happy face on the kids’ bracelets. In my feeble attempt to humanize this process, I looked up at the mother again, and through the cover of face masks, we smiled at each other. I saw tears. As a mother of two young children, I can attest to the challenge of traveling with small human beings—the constant demand for attention, snacks, the bathroom.

But I have never had to flee a country with just the clothes on my back and with children in tow. I have been tired but not so exhausted that the mere act of holding up an arm for another identity tag would set off tears. I wanted to tell her: “It’s all right now. You’re safe. Everything will be OK.” But, of course, I couldn’t. I couldn’t even tell her where they were going next. I didn’t know.

I wanted to ask her about how she came to sit before me, what her background was, her story. Getting to know the people we work with is a vital part of our jobs as USAID officers. It sensitizes us to their struggles, helps us shape programs to meet their needs, and places a human face amid budgets and bureaucracy. It wasn’t the time or place to ask such questions. The line was long behind her, and she was eager to move on.

We finished the intake process, and the mother and her children moved on to the next step in their journey. I hope this phase of their transition is going well, and they are settling into their new home, here in our country.

U.S. SAFE HAVENS

Calling All Americans: Welcome the New Arrivals

VARIOUS U.S. BASES

Kathleen M. Corey

Afghan women with veiled faces trying to keep sand from their eyes during a windstorm at Fort Bliss. Laughing children playing a game of pick-up soccer with Marines at Quantico. Afghan men at Fort Pickett asking if their wives will have to work to make ends meet and, if so, who will take care of the children. Young women at Camp Atterbury worried about how they will support themselves in the United States.

These are images I will carry with me for a long time. After eight weeks at these bases implementing a cultural orientation program designed by the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration–funded Cultural Orientation Resource Exchange, I have many lasting memories of my time at the “safe havens” around the United States.

Some of my most difficult moments came when Afghans approached me after cultural orientation classes. A veiled woman with tear-filled eyes showed me pictures of her badly beaten father, mother and brother in their coffins, killed by the Taliban. A man showed me a photo of a beautiful little girl, his niece, killed in the airport bombing. Grown men wept as they told of family members still in Afghanistan, fearful of Taliban reprisals.

As a retired Foreign Service officer, I know that interagency cooperation can fall victim to competing priorities. Not so at the safe havens. All of us, from numerous federal agencies, huddled together, often in a big tent, worked long hours, sometimes seven days a week, to provide the guests with adequate and culturally appropriate care. Sleeping quarters—huge tents and barracks—were kept cool and then, as the months went by, warm.

Halal food was prepared, and makeshift mosques were created. Resettlement information, legal advice, and English and cultural orientation classes were offered. There were recreational activities: movies for children; yoga classes for women; chess, volleyball and cricket for men. At Afghan music events, separate groups of men and women danced their hearts out.

More than 40 percent of arriving Afghans are children, and it was always a joy to see their happy, playful faces. Their drawings of the U.S. flag surrounded by hearts were on display in classrooms, and wherever we went, we were greeted by their bright smiles, fist bumps and “Hello! What you name?” A new generation of Americans, full of hope for the future.

In the 1980s, I worked for nine years in Southeast Asian refugee camps in another PRM-funded program. The contrast between then and now is striking. Then, well-staffed resettlement agencies had time to prepare for the newcomers. Today, after years of sharp reductions in refugee admissions and at a time of shortages in affordable housing, severely understaffed resettlement agencies have very little time to prepare for the sudden arrival of tens of thousands of Afghans.

And just when resettlement agencies were beginning to rebuild under a revitalized global U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, they face the daunting task of resettling thousands of additional Afghans, anxious to find work so they can send money back to relatives who remain behind in a country on the brink of economic collapse.

There remains much to be done to help these future Americans successfully adjust to their new lives. As three resettlement agency CEOs put it in a Washington Post op-ed, “This is an all-hands-on-deck moment for refugee resettlement in this country.”

When refugees fled Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, our government and the American people did the right thing, warmly welcoming them into homes and communities across the country. It is my fervent hope that we will continue working with the same generosity and sense of responsibility in support of our Afghan allies.

Building Safe Havens for Allies

DULLES, FORT DIX, FORT PICKETT

John Wecker

A women’s cricket match at Fort Pickett in Virginia.

John Wecker

I watched the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban in August with a broken heart. It unfolded as I was taking the Foreign Service Institute’s two-month job search program, preparing to retire following a 30-year career as a Foreign Service officer and three tours in Afghanistan. When I saw the department’s call for volunteers to respond to the crisis, I, along with 25 colleagues in the retirement course, immediately signed up, choosing to spend the last five weeks of our course time helping our Afghan friends wherever and however we could.

My first volunteer assignment was to Dulles International Airport, helping to set up a facility for relocated Afghans entering the country. We were in a rush to secure everything from space to food, to information, so we could be prepared to welcome Afghan families to our country. Large groups of new arrivals poured off the buses from the airport into our makeshift facilities, all after fleeing for their lives from the chaos and danger in their home country.

After five days at Dulles, I was asked if I could go to Fort Dix in New Jersey, to help establish that safe haven facility. I drove up the next day, hoping my travel authorization and laptop would somehow catch up to me (they did).

The next weeks were a blur of 14- to 18-hour days as the military scrambled to turn barracks and empty fields into housing for up to 12,000 Afghans, with all the life support services that entailed, and we on the civilian side scrambled to bring all the necessary arms of the interagency and NGO communities together to welcome, process and eventually move the Afghans from the safe havens on to their new lives in America. “Building the plane while flying” became our catch phrase.

After a month at Fort Dix, and approaching my official retirement date, PRM asked if I would be interested in continuing this work as a reemployed annuitant. Of course I said yes, and after a few weeks of HR processing, I moved down to Fort Pickett to lead the State Department effort there. By this point, the “landing pads” had evolved from panic-tinged startups to functioning machines; the plane was built, although it still required constant improvements, and we had moved on to a new phase—caring for the thousands of Afghans on U.S. military bases and moving them along to their new homes and lives in America.

At both Fort Dix and Fort Pickett, I’ve found just walking around the villages on base talking to people, getting stomped at chess, sharing a cup of tea or horsing around with the many children has been a blast. We’ve had free rein to come up with morale, welfare and recreation (MRW) activities, alongside our NGO partners. At Pickett the State/USAID/Peace Corps/AmeriCorps team has conducted cricket, soccer and volleyball tournaments (men’s and women’s); computer and ESL classes; basketball camp; Bollywood movie nights; a very popular women’s center with everything from teas, sewing, computer and cultural orientation classes; and even a skateboard camp with the help of a talented young woman skateboarder from Kabul.

This work has been tremendously challenging, both emotionally and physically, but also the most fun I have ever had as a diplomat. I look forward to helping this most deserving community of friends as I move into (actual) retirement.

Domestic Diplomacy for Resettlement Efforts in Virginia

FORT PICKETT, VIRGINIA

Baxter Hunt

Afghan evacuees stroll at Fort Dix in New Jersey.

John Wecker

I was part of a group of 19 State Department and USAID staff working at Fort Pickett, an Army National Guard training facility in southern Virginia that was one of eight military bases around the country housing Afghan evacuees. The first group of Afghans was bused from the Dulles Expo Center to Fort Pickett on Aug. 28, and by the end of September we were hosting 6,000 evacuees.

Several of us on the State/USAID team had served in Afghanistan, and all of us were gratified to be able to assist locally employed staff colleagues—100 of whom wound up at Fort Pickett—and other Afghan partners in their time of need. We worked with our colleagues from the Department of Defense and other agencies to set up, in a matter of days, housing, medical care, life support and resettlement processing for our Afghan guests.

In addition to our support to the evacuees, we devoted significant time to building goodwill with the local community in and around Blackstone, Virginia. Two days after the first Afghan guests arrived at Fort Pickett, the mayor of Blackstone, also the owner of the local newspaper, paid an unofficial visit to the base and published a series of photos and a story raising concerns about how the influx of Afghans would affect his town of 3,300 people.

We quickly arranged the first of a series of meetings with the mayor and assured him that the Afghans did not pose a threat to the town’s safety, health or public resources. Ultimately, the mayor proved to be an ally, pushing back on wild rumors and helping us reassure congressional delegation (CODEL) visitors.

While basic medical care at Fort Pickett was provided through a contract with SOS International, Afghan evacuees with emergency needs had to go to small local hospitals that were already over-run with COVID patients. Twelve babies were born to our evacuees during that first month, and local hospitals raised the alarm over capacity issues with Virginia’s Department of Health.

We were able to provide daily statistical updates to show that the volume of Afghan patients was not out of control. We also brokered an agreement between SOS International and a local Walmart pharmacy that allowed Walmart to fill essential medical prescriptions for our Afghan guests, which avoided adding to the number of hospital visits.

Local residents were deeply divided in their attitudes about the Afghans. Some saw them as a threat, and when they encountered an Afghan off the base—and many Afghan Americans, interpreters and others showed up in Blackstone—they often went on social media to report an “escapee.” But many local residents opened their hearts and wallets in support of the evacuees. In addition to generous individual donations, a local church allowed members of Team Rubicon, a military veterans nongovernmental organization that was a vital conduit for receiving and distributing donations, to sleep at the church for weeks on end.

I am hugely proud of our team’s support to our Afghan partners, and it was good to see how well our diplomatic skills transferred to working with a domestic audience in southern Virginia.

A POLAD’s Perspective

JOINT BASE MCGUIRE-DIX-LAKEHURST, NEW JERSEY

Holly Peirce

Evacuees arrive at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey.

John Wecker

I found myself as the sole State Department foreign policy adviser (POLAD) at the North American Aerospace Defense Command and U.S. Northern Command in mid-July when the crisis planning began for Operation Allies Refuge. The senior Department of Homeland Security representative and I explained the intricacies of visas/parole and DHS/DoS authorities to USNORTHCOM planners. As I kept the State POLAD network and Bureau of Political and Military Affairs informed, I shared and “interpreted” State reporting, which was fed into the overall planning process. It felt like a State Department integrated country strategy on steroids, with dozens of complex multiagency taskers.

As the evacuation operation progressed, the decrease in classification level from SECRET to For Official Use Only / Sensitive But Unclassified greatly facilitated virtual, interagency communication and after-hours coverage. Given the uniqueness of the mission, the USNORTHCOM liaison officers at the Afghanistan Coordination Task Force, the Unified Coordination Group and I answered what seemed like never-ending requests for information from planners. What started as highly complex planning under State Department direction for a limited number of Special Immigrant Visa applicants at Fort Lee, quickly morphed into a historic evacuation as the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan, and DHS became the lead federal agency.

So-called lily pads were established overseas to temporarily house evacuated Afghans. Meanwhile, State and Defense worked to overcome early systems integration challenges to track arriving passengers. USNORTHCOM, originally tasked to house 20,000 Afghan evacuees, was quickly responsible for 50,000. Housing turned into wraparound services for our guests, and capacity grew closer to 65,000 across eight DoD task forces, known as safe havens. Impressively, planning for resettlement of evacuees started before operations had even stabilized, as DoD supported DHS’ overall effort. And, of course, there is a DoD plan for everything—including a nascent USNORTHCOM plan for gender advisory support to the lead federal agency in such missions.

Given the accelerated pace of evacuation, USNORTHCOM’s Women, Peace and Security team did not initially have biodata to review sex and gender disaggregated data. But that did not stop us from drafting an initial concept of operations to protect vulnerable populations. Across the DoD there is an emerging cadre of Joint Staff–trained professionals working on gender issues (including this deputy POLAD). For the first time, USNORTHCOM piloted voluntary gender advisory support by DoD personnel to all eight Operation Allies Welcome task forces (along with interpretation support).

The USNORTHCOM lead team provided onsite expertise on integrating gender-based considerations into DoD support to the welcome effort. Some safe havens, such as Task Force Liberty at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, where I had the honor of serving, formed interagency female engagement and community outreach teams (FETs) to ensure equal access to information and services and protection of vulnerable populations—be it ensuring equal access to winter clothes, appropriate maternity care and nutrition, or English classes and education on U.S. cultural norms and expectations.

I feel privileged to have participated in this onsite implementation firsthand after working on Operation Allies Welcome at the headquarters level for months. Both DHS and the interagency now recognize the value of gender advisory support and have requested its continuation for current operations. DHS also included a gender advisory role in the Gender and Vulnerable Population Protection Standard Operating Procedures. On Dec. 29, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced the appointment of two senior officials at the State Department focused on supporting the civil and human rights of Afghan women and girls—both those remaining in Afghanistan and resettling in the United States.

With these initiatives, we now have the opportunity to translate informal feedback from those on the ground into formal and more permanent lessons learned across the interagency. This will help us to operationalize interagency gender support for future domestic and overseas humanitarian assistance responses, so that it is routinely incorporated into guidance for defense planning and deployments.

“Beautifully Human” Work

JOINT BASE MCGUIRE-DIX-LAKEHURST, NEW JERSEY

Rick Matton

Beautifully human are the two words that come to mind when thinking about how to describe the resettlement efforts that were ongoing at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst (JBMDL) when I arrived in November 2021. At the time, there were more than 12,000 Afghan guests temporarily residing on this large military base. To support them, an interagency task force comprising more than 25 federal agencies and NGOs had been established in August to perform a mission that was unprecedented in our nation’s history.

I joined the task force as part of a small State Department team sent to assist with the resettlement of these guests. On arriving, I was placed on a smaller team whose stated mission was to assist the hundreds of locally engaged (LE) staff, who had previously worked at U.S. Embassy Kabul, get in-processed to the base and then resettled into communities across the United States as quickly as possible.

Our smaller team’s actual mission, however, turned out to be far larger in scope. While we certainly kept the LE staff as our number-one priority, our small team’s office also became a respite for many other Afghan guests to come in and just be able to speak to someone about their specific case. Yes, there were frequent town hall meetings in which information was given out about the resettlement process, but often our guests craved one-on-one attention from someone who cared about their situation and would provide some comfort simply by listening to their concerns.

One instance of such comfort and care was truly “beautifully human.” At the end of a busy day spent largely providing case updates to our LE staff colleagues, a young woman walked into our office looking distraught. She sat down at our desk, and the first thing she said was: “I want to go back to Afghanistan.” She then immediately broke down in tears. As she began to tell her story, it became evident that her husband was emotionally abusing her.

I watched as my two female colleagues assured her that we would take care of her by moving her to a different village on the base, away from her abusive husband. At the same time, this young woman was very concerned about keeping the matter discreet on the base. My colleagues provided her assurance that her privacy would be respected.

After a very emotional hour, the young woman wanted to remain in our office to allow the redness and tears in her eyes to subside before going to her new housing assignment. Finally, she was ready to face the world again; my colleagues had done such an amazing job comforting her that the young woman no longer wanted to return to Afghanistan. Instead, she decided the best thing for her to do would be to contact a close friend in New York City and start her new life there.

The empathy and genuine compassion my colleagues showed this young Afghan woman was just one example of the work going on here at JBMDL. I am proud to be part of the interagency team undertaking such an enormous effort to bring peace and comfort to the lives of more than 120,000 Afghans who are resettling in the United States.

The Desire to Help Was Contagious

FORT BLISS, NEW MEXICO

Minal Amin

A session on résumé writing and employment opportunities is conducted in the Women’s Tent at Fort Bliss.

Minal Amin

I watched as events unfolded on Aug. 15, 2021, stunned and in a state of disbelief by what was transpiring in Afghanistan. The United States was less than a month away from the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, and the Taliban was again taking control of a nation that the U.S. government had actively supported throughout two decades.

When USAID presented the Afghanistan-related detail opportunity, I immediately knew this was a unique moment that I couldn’t pass up. I knew very little about the assignment, but that didn’t matter. I knew nothing about the location to which I would eventually be assigned; that, too, didn’t matter. Paramount was the opportunity to help those who had lost everything and support them in rebuilding their lives in a new country—a country I call home.

I was assigned to the Department of State team at Doña Ana village at Fort Bliss in New Mexico. This location is described as the most austere of the eight military installations where Afghan guests reside. By many accounts, it is indeed quite austere.

My first week there revealed, however, just how impressive the operation is. The U.S. Army stood up the “village” in a matter of three or four days. A range of essential services are provided to our Afghan guests including nutritious and plentiful meals throughout the day; good quality medical care, including mental health services; educational opportunities for both children and adults (of the eight bases, Doña Ana has the only established informal school); a play area for kids; a dedicated Women’s Tent; sporting events; and more.