Winter in Kabul, 2005

Reflections

BY MARC GILKEY

The ever-present mountains of Afghanistan, the Hindu Kush, is a great watershed that supplies rivers that can serve as hubs of agricultural production and economic growth in the country. But a lack of modern farming methods, including irrigation development, and dependence on erratic weather patterns, have made farming difficult and limited output to a fraction of its potential.

Courtesy of Marc Gilkey

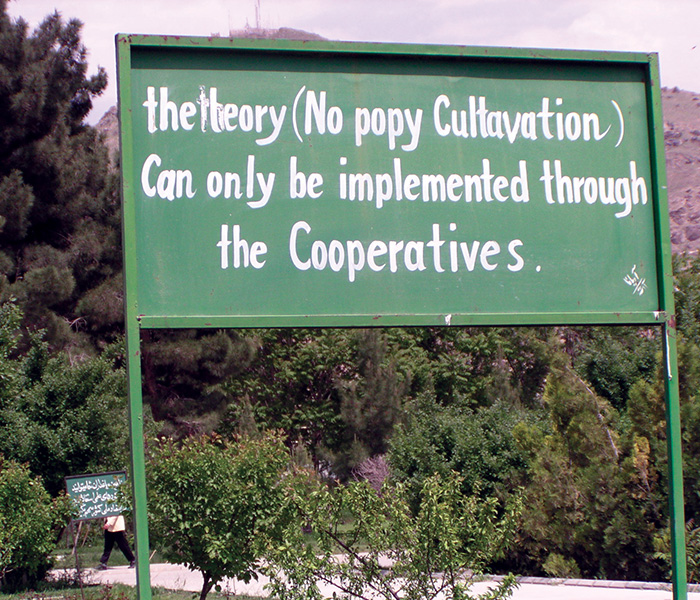

Cooperatives have a vital role in any effort to move away from poppy cultivation toward more diversified and productive agriculture in Afghanistan. They are the transmission belt for the specialized training USDA delivered in areas such as fertilizer management, animal husbandry, and plant and animal disease control to Kabul University’s colleges of agriculture and veterinary science around the country.

Courtesy of Marc Gilkey

I arrived in Bangkok in August 2021 and was in quarantine for two weeks when the events at the Kabul airport unfolded. Sitting in a hotel room and feeling quite helpless, I reflected on my year in Afghanistan—a lifetime ago, it seemed.

I also thought about the work done around the world by the United States Department of Agriculture, which President Abraham Lincoln described as “The People’s Department” at its creation in 1862.

With USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, I have enjoyed an abundance of experiences and opportunities, and as I consider the numerous chapters, none have been more memorable than the time I spent in Afghanistan.

During the winter of 2004, USDA was instructed by then-President George W. Bush to place agricultural advisers in the provincial reconstruction teams (PRTs) in Afghanistan, so that expertise from the department could be applied to meet technical needs for the reconstruction of Afghanistan’s agricultural sector.

As a platform for reconstruction efforts, the PRTs were an alternative model that combined both security and reconstruction. USDA technical expertise would be strategically placed in the PRTs throughout Afghanistan.

A call for volunteers was sent throughout USDA, and I could not resist this challenging opportunity. Before long, on New Year’s Day 2005, I was on a plane to Kabul. After an emergency stop in Azerbaijan, we touched down at Kabul International Airport, which would later be called the Hamid Karzai International Airport and, most recently, was the backdrop for great sadness and desperation.

Winter in Kabul is cold, crisp and quiet, at least it was in January 2005. On the ground, USDA had 10 volunteers from an array of agencies: Natural Resources Conservation Service, Food Safety Inspection Service, Farm Service Agency, Food and Nutrition Service, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

Our lifeline in Washington, D.C., was Otto Gonzalez of the Foreign Agriculture Service; without the support of his team, we would have been rudderless.

My job seemed simple. As the USDA provincial reconstruction team coordinator, I would have the luxury of staying in Kabul in a warm “hooch”—basically a modified shipping container—and developing strategies to advance the rebuilding of the agricultural sector.

The reality was a bit different: I was to be behind the scenes and do everything possible to clear the path for my colleagues who were sent to the front lines in Herat, Kandahar, Jalalabad, Helmand, Parwan and beyond.

Working in Kabul at the embassy also gave USDA a seat on the country team, which enabled critical coordination with both the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development. The importance of diplomacy and development in strengthening the agricultural sector in Afghanistan cannot be emphasized enough.

For the first six months of 2005, the atmosphere was quite permissible for movement within Kabul and back and forth among the numerous PRTs, as well. I visited the Ministry of Agriculture regularly and even had a satellite office there. The goal was to help build the ability of the Afghan central government to support and provide services to the agricultural sector.

The aim was to implement a national strategic plan that addressed broad areas of need in the agricultural sector. Many hoped to create export markets for specialty products—pomegranates, grapes, raisins and a plethora of dried fruit products—all of which were meant to be an alternative to poppy production.

Looking for and evaluating alternative livelihoods for Afghan farmers and villagers, I was repeatedly forced to acknowledge the stark realities of everyday life in Afghanistan. Electricity and running water were sporadic, and necessary supplies were difficult, if not impossible, to access. Seeds, root stock, fertilizers and animal vaccines were needed to revitalize the agriculture sector.

The author (front right) shares extension materials for improving crop protection and production with Afghan farmers, experts and officials at Afghanistan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock.

Courtesy of Marc Gilkey

The arrival of summer brought several bombings of internet cafés in Kabul and a very quick tightening of security. Visits to the ministry became more complicated, though more important than ever.

Amazing work at the PRTs continued: reforestation, soil conservation, poultry production, microloans, irrigation, animal vaccinations and plant protection. This team really showed what USDA could deliver.

At meetings, a State colleague would introduce me as the “secret weapon,” always clarifying that USDA was neither secret nor a weapon, but a known entity—think Green Revolution and Food for Peace—that was welcome at official and rural doorsteps around the world. It was a time of great hope in Afghanistan.

As the year continued, I received my onward assignment to Mexico. I left Kabul in late 2005 with a feeling of confidence that a better day would dawn. My counterparts at the Ministry of Agriculture and the farmers I had met were all eager to embrace change, and our interventions were making a difference.

One night, after I returned to Washington in December 2005 to get my car for the drive to Mexico City, my boss called me. “We need you to pick something up at Dulles airport for an event at the Embassy of Afghanistan,” he said. The menu for the planned event featured Afghan pomegranates and grapes, which required a special-use permit with the condition of 100 percent inspection and safeguarding.

This meant I would drive my Ford Escort to Dulles, retrieve the small shipment from a Customs and Border Protection officer, inspect it thoroughly for bugs and diseases and, finally, drop it off at the embassy.

Naively, I wore a suit, thinking I would be invited into the embassy event. I went to the back entrance as instructed and delivered the produce to the American staff, who took the package and barely acknowledged me. As I returned to the parking lot, I saw the Afghan drivers and guards. Placing my right hand over my heart, I nodded to them.

Instantly they smiled and returned the gesture. We drank hot kahwah (tea) out in the parking lot, and I regretted not keeping one pomegranate for further inspection. Loosening my tie, I could hear the distant chatter of the party and realized I was exactly where I belonged, where it was cold, crisp and quiet.

In the years since, as the U.S. intervention ground on under the banner of constantly changing goals and priorities, I have often been asked by people who never touched Afghanistan if I wasted my time there.

Rather than respond with a yes or no, I would describe my experiences sharing knowledge and working with the Afghan people: giving lectures at the university, providing veterinary publications to aspiring veterinary students, planting trees, growing asparagus and drinking hundreds of cups of tea.