Time to Bring Back Legations Headed by Diplomatic Agents?

Speaking Out

BY GERALD LOFTUS AND STUART DENYER

Speaking Out is the Journal’s opinion forum, a place for lively discussion of issues affecting the U.S. Foreign Service and American diplomacy. The views expressed are those of the author; their publication here does not imply endorsement by the American Foreign Service Association. Responses are welcome; send them to journal@afsa.org.

Readers of the amusingly satiric stories of mid-20th-century English writers Evelyn Waugh and Lawrence Durrell would recognize diplomatic missions called legations, and they wouldn’t associate “diplomatic agents” with security. The terms are redolent of top-hatted diplomats in capital cities of the 1930s and 1940s. Indeed, that era was their swan song.

By the 1960s—for the United States, the last American legations in Budapest and Sofia were elevated to embassy status in 1966—“legation” had become an antiquated term. After President John F. Kennedy’s “diplomatic universality” policy resulted in the establishment of dozens of full embassies in newly independent African nations, those American legations in Eastern European communist capitals truly seemed like holdovers from the past.

And yet, our question: Is it time to bring back legations? Likewise, “diplomatic agencies,” which indicated an additional diplomatic as opposed to purely consular function at American consulates and consulates general? Would a legation offer an alternative in future situations—North Korea, Taliban Afghanistan come to mind—where the U.S. would want to establish more than an “interests section” housed within a foreign embassy, but less than full embassy status with an ambassador? What would this type of diplomatic representation mean in practice?

There are still hints of the previous ubiquitous nature of legations—for example, “ALUSNA,” or American Legation United States Naval Attaché. Though it was originally used as a cable address, American naval attachés in U.S. embassies throughout the world continue to hold this title despite the fact that the last legations closed their doors (or rather, were renamed “embassy”) more than a half-century ago.

Many of America’s founders were ministers of legations: Benjamin Franklin was the very first (to France, succeeded by Thomas Jefferson), and John Adams was the first American minister to the former mother country, Great Britain. Even the Chevy Chase section of Washington, D.C., has a Legation Street.

What Is a Legation?

The American legation’s iconic “Arab Pavilion” building in Tangier, Morocco, from the 1930s.

Tangier American Legation Institute for Moroccan Studies

What is (or was) a legation? A better start might be to ask what an embassy is, because in its original sense, an “embassy” was a temporary mission. A king would send a noble to represent him on “an embassy” to another monarch, “ambassador extraordinary” connoting a special mission. His “embassy” might last months, and he’d hopefully return with a promise of trade, or a treaty. It wasn’t until the Renaissance that resident ambassadors (“ordinary”) began to appear, but the high cost of their upkeep encouraged some nations to appoint ministers, who headed legations.

The diplomatic pecking order in European capitals gave precedence to ambassadors from other monarchies. Just as the United States was slow to provide its diplomats with uniforms commensurate with those of foreign diplomats (and eliminated them entirely in 1937), it chose not to name its top diplomats “ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary.” At its outset, diplomats of the American republic were literally alone among representatives of kingdoms, and so America’s default chief of mission was a minister—of a legation.

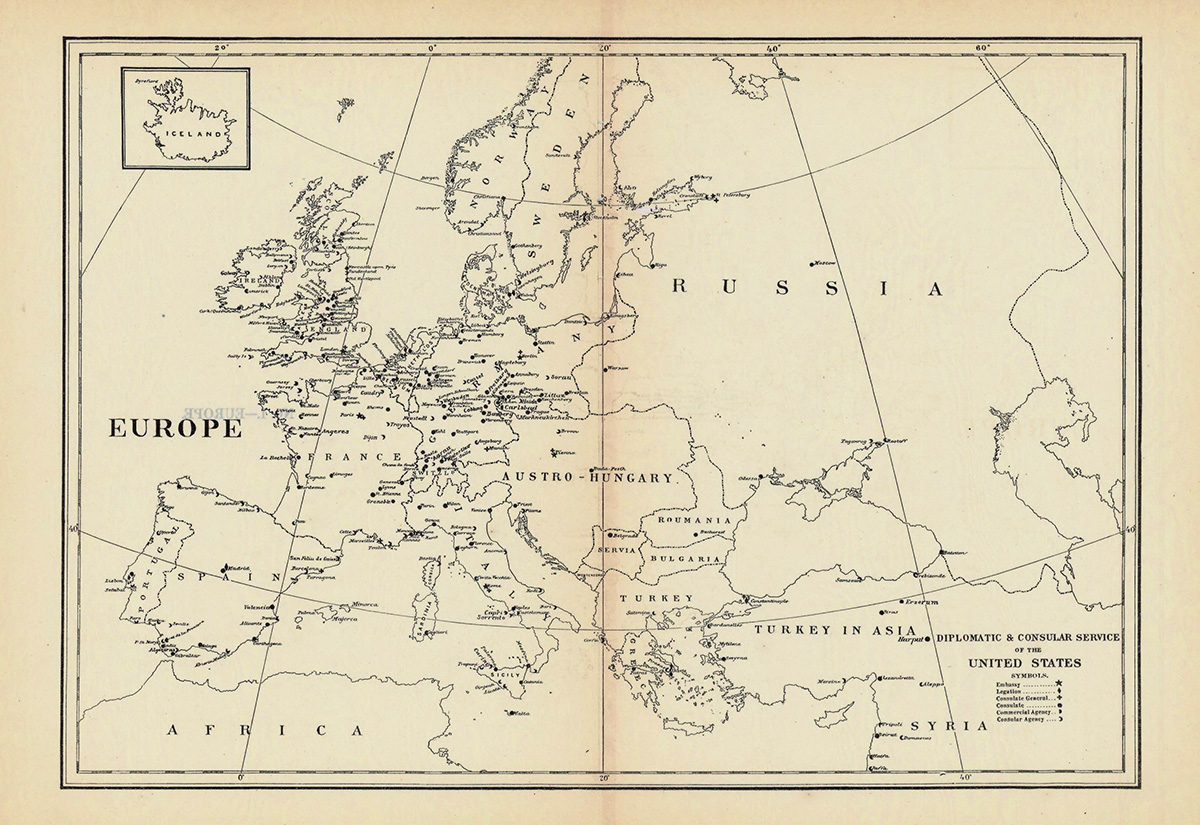

The State Department’s Ralph Bunche Library map collection, especially the series “Diplomatic and Consular Offices” (later “Foreign Service Posts”), shows the evolution between 1888, when U.S. legations were the norm, to 1903, when entries for “embassies” take the lead in the map key. (See maps below.) Writes the Office of the Historian: “The United States only sent and received Ministers prior to 1893. Until 1893, the United States was not considered a major power, therefore the highest-ranking diplomatic representatives that it sent or received were Ministers of one sort or another.”

An 1893 news clipping datelined Paris and titled “France Returns the Compliment” recounts how the French parliament was pleased to reciprocate the U.S. elevation of its legation in Paris with a similar designation of its Washington, D.C., legation as an embassy.

If an embassy was originally a sort of exceptional “TDY” or “temporary duty assignment,” to use current State Department jargon, a legation was a permanent diplomatic mission, a brick-and-mortar representation of a country in a foreign capital. The State Department’s Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations maintains the Secretary of State’s “Register of Culturally Significant Property,” and it includes two American legation buildings that remain U.S. government property to this day. The Old American Legation in Seoul, South Korea, serves as a guest house on the grounds of the American ambassador’s residence.

The Tangier American Legation is another matter, serving as a museum, cultural and conference center, and research library. As the first American diplomatic property, gifted to the United States by the sultan of Morocco in 1821, it is the only U.S. National Historic Landmark in a foreign country. And online, it has a monopoly on the “legation” URL: www.legation.org.

But if readers in the U.S. want to see a legation without leaving the country, they can visit the French Legation Museum in Austin, once home to the French mission to the short-lived Republic of Texas (built in 1841). In Washington, D.C., several venerable buildings on Embassy Row (for example, the Embassy of Luxembourg) were once legations when their countries hosted American legations.

An Idea Whose Time Has Come, Again?

A standard legation seal, or “vignette.”

Tangier American Legation Institute for Moroccan Studies

The embassy-legation equation was an indication of the relative ranking of sending and receiving countries (and of reciprocity, i.e., minister for minister, ambassador for ambassador). But while they existed, legations also afforded flexibility to American presidents and Secretaries of State in terms of assignments for senior diplomats. Though ministers were appointed with the consent of the United States Senate, sometimes assignments slipped through.

John Carter Vincent, a senior China expert under a cloud because of the Cold War anti-communist hysteria and therefore unlikely to receive Senate confirmation, could be assigned as the “diplomatic agent with rank of minister” at the U.S. Legation in Tangier, the longtime diplomatic capital of Morocco. At the time of his appointment in 1951, The New York Times wrote: “For his new post in Tangier, Mr. Vincent will not require Senate approval.” This might also have been possible because of the assignment’s somewhat unique status (Tangier was still the consortium-ruled International Zone, but Vincent was also accredited to the French Protectorate).

The tool kit available to American administrations in the past was much more varied than the current “ambassador or bust” approach. At various points, for example, the Tangier American Legation changed status over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. Depending on the vagaries of colonial rule or whether the U.S. and a protectorate power were allies (in the case of the U.S. joining with France in World War I), nomenclature for the American representation in Tangier went from consulate to consulate general to legation to diplomatic agency, and, finally, when Morocco regained independence in 1956, an embassy was opened in its capital, Rabat.

Fast forward to the 21st century and the challenges to American diplomatic representation. Month after month of senatorial holds on presidential nominations for coveted ambassadorial appointments can certainly discourage career officers, but the phenomenon might also encourage political donors to look for other rewards. If the United States decided to reestablish legations and diplomatic agencies in certain circumstances, the pull of a mere (and let’s face it, “foreign” sounding) “minister” rank as opposed to the lifetime “ambassador” honorific might further discourage those seeking political appointments.

In the interim, as dozens of countries wait for the senatorial logjam to break and finally receive their American ambassadors, aren’t Foreign Service deputy chiefs of mission and other chargés d’affaires in effect serving as “ministers” in de facto “legations”?

But rather than this back-door approach to embassies without ambassadors, why not entertain the notion of a fully constituted mission called a legation or a diplomatic agency? In some future scenario, we could imagine a modus vivendi with the regime in North Korea, where a settlement on the nuclear issue could result in an exchange of ministers at their countries’ respective legations.

Likewise, after many issues are resolved, and if the Taliban prove their bona fides as a government, the United States might entertain sending a small team under the aegis of a minister or a diplomatic agent, perhaps to a legation building that—unlike its sprawling evacuated embassy chancery—wouldn’t be associated with what would be seen by many Afghans and Americans as its recent pro-consular past.

The United States conducted its first century of diplomacy without embassies or ambassadors. Perhaps we can consider a place for legations, diplomatic agents and ministers once again.

Map 1: 1888

Map 2: 1903