Small but Mighty: APHIS Turns 50

APHIS’ compact cadre of FSOs are on the front lines keeping American agricultural trade healthy, flowing and growing around the globe.

BY KAREN SLITER AND RUSSELL DUNCAN

APHIS entomologist John Welch, at left, and Panamanian screwworm personnel collecting a myiasis sample from a calf in the Darién Provence of Panama in 2015.

COPEG

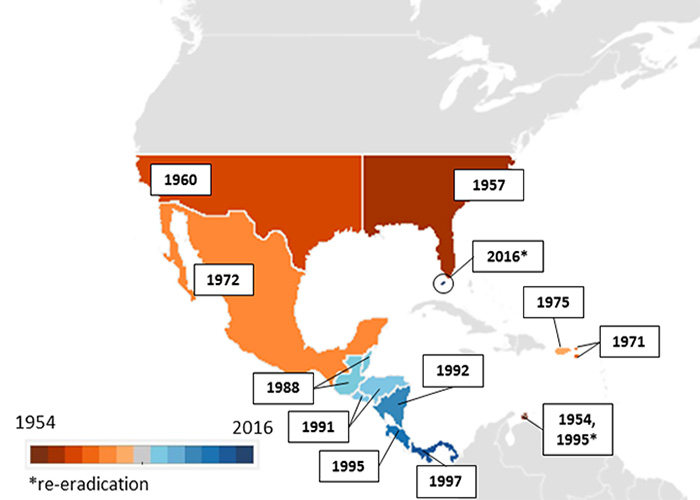

The USDA has been instrumental in building and maintaining a barrier against the New World screwworm in the Americas and pushing that barrier down through Panama. The map above shows the progress of New World screwworm eradication programs by their start dates.

USDA

This month, U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service—an 8,000-strong agency that safeguards U.S. agriculture from foreign pests and diseases—celebrates its 50th anniversary. Playing a critical role in the festivities will be the APHIS Foreign Service, a small but mighty team of some 30 FSOs working in 28 countries with about 300 locally employed staff. This compact cadre might not be a policy kingpin at country team meetings, but it punches far above its weight in helping to keep American agriculture and trade healthy, ensuring our country’s economic viability, safeguarding our food security and sustainability, and controlling diseases that can affect plants, animals and humans.

APHIS FSOs have a unique “dual career” profession. In addition to being skilled professional diplomats, they must also be technical specialists in such areas as veterinary medicine, plant pathology, entomology and biology. Their jobs can cover myriad activities: conducting formal and informal trade negotiations, communicating APHIS biotechnology policies, serving on international scientific committees and strategic groups for organizations such as the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the Food and Agriculture Organization, and reporting on plant and animal pests and diseases (including zoonotic diseases that pass from animals to humans, such as COVID-19).

Ultimately, an APHIS FSO’s work affects everything from the availability and price of grapes in U.S. supermarkets in January to which foreign markets are open for the approximately $150 billion of U.S. agricultural exports, and whether the outbreak of a significant plant or animal pest or disease that could cause hundreds of millions of dollars of damage on U.S. soil can be prevented. So, the next time you are seated next to an APHIS colleague at a country team meeting, take another look. Our work has a greater impact on American life and prosperity than you might have known!

U.S. Ambassador William Kennard, at left, and Mrs. Kennard visit the APHIS bulb preclearance program in the Netherlands in 2009.

APHIS Brussels

The USDA before APHIS

Dutch tulips.

Karen Sliter

The APHIS Foreign Service embodies USDA’s longtime commitment to ensuring that foreign pests and diseases do not harm American agriculture or trade—a goal the department vigorously pursued well before it created APHIS in 1972. A notable example is the fight against foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), a deadly livestock illness that was eradicated from the United States in 1929. With the advent of a serious FMD outbreak in Mexico in 1947, President Harry Truman signed a bill authorizing the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture to offer aid to “protect vital U.S. interests.” USDA veterinarians worked with their Mexican colleagues to achieve eradication in that country by 1954.

During this same period, two other highly significant pests were threatening U.S. agriculture, namely the New World screwworm (NWS) and the Mediterranean fruit fly (or medfly). To bring them under control, starting in the 1950s the U.S. developed a technique for using radiation to sterilize the male fly of the screwworm. APHIS then worked with the International Atomic Energy Agency on its large-scale implementation. Building on that success, the same strategy was later applied to the medfly. Eradication of both pests was achieved by decreasing the overall number of flies with conventional chemical sprays, followed by the release of sterile males to flood the “wild” male population and reduce the number of offspring.

For more than six decades now, the United States has worked with foreign countries, as well as the IAEA, to gradually eradicate screwworm from the southern U.S. through Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, then Nicaragua and Costa Rica, and on down to Panama, where an “insect barrier” is maintained by dispersing 4.7 million sterilized screwworms each week into the rainforest area of the Panama-Colombia border. For medfly, a containment barrier has been established in Guatemala, with as many as 1.3 billion sterile medflies being released each week. In both cases, cooperative agreements with Panama, Guatemala, Mexico and other countries ensure the smooth administration of the programs.

In its first decade, APHIS’ new Foreign Service focused primarily on operational efforts—for instance, building capacity in Haiti and the Dominican Republic to eradicate African swine fever.

Screwworms can infect any living, warm-blooded animal. This includes not only livestock and wildlife; screwworms can and have also infected people. (The screwworm’s scientific name is C. hominivorax, or “man eater,” after a horrific outbreak among prisoners on Devil’s Island, an infamous 19th-century French penal colony in South America.) The larval stage of the fly bores into wounds and eats living flesh, causing disfigurement and, in some cases, death. Screwworms once killed millions of dollars’ worth of cattle every year in the southern United States from Florida to California and infected deer, squirrels, pets and the occasional human, as well. So, in addition to protecting public health, the eradication of NWS generates some $900 million in benefits to U.S. producers, according to the USDA, and some $2.8 billion per year in general economic benefits.

The medfly is similarly devastating for fruits and vegetables. It affects the production and trade of more than 300 varieties of fruits and vegetables and is considered one of the most important agricultural pests in the world. The cost-benefit ratio of controlling medfly has been estimated at more than 150 to 1, with tens of billions of U.S. dollars per year in benefits for the United States.

One of the few “all hands” photos of the APHIS Foreign Service and HQ support staff that exist, taken in 2004. For many years, APHIS FSOs numbered between 50-60; today it is 30.

Courtesy of Karen Sliter

One Department, Two Foreign Services

To help bring the 2001 U.K. foot-and-mouth disease outbreak under control, and protect U.S. livestock, APHIS veterinarians worked in the U.K. diagnosing infected animals, supervising slaughter and supporting U.K. farmers. Here APHIS vets (Karen Sliter at right) share a rare moment of levity and stress release during what were 18-hour workdays. Personal protective equipment was essential, and the vets had to “scrub in” anew at each farm to prevent disease spread.

APHIS Vienna

By the early 1970s, the world was changing rapidly, and nowhere more than in the arena of agricultural commerce. As free trade policies allowed more agricultural goods to be shipped around the world, consumers everywhere demanded more agricultural imports, such as fruit, that could be available year-round.

But with these welcome developments, and a surge in tourist and business travel, came increased risks of introducing serious animal and plant diseases or pests. To consolidate its response to potential agricultural threats, USDA launched APHIS on April 2, 1972. And just eight years later, the Foreign Service Act of 1980 granted U.S. Foreign Service status to USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service and to “other personnel” in the department deemed “necessary.”

When APHIS was also granted Foreign Service authority in 1982 through Executive Order 12363, USDA became the only federal department with two separate Foreign Service agencies, each with a distinct, but complementary, mandate. The Foreign Agricultural Service, with 147 members today, links U.S. agriculture to the world to enhance export opportunities and global food security through a global network of nearly 100 offices covering approximately 180 countries. A typical background of an FAS FSO is agricultural economics; FAS officers publish production forecasts and other market intelligence, break down barriers to U.S. food and agricultural exports, promote U.S. agricultural products (from pregnant heifers to wine) and implement trade capacity building programs. In contrast, APHIS’ Foreign Service veterinarians and plant specialists apply their technical expertise to ensure safe trade, facilitating the negotiation of science-based animal and plant health trade agreements and monitoring and reporting on serious plant and animal pests and diseases to prevent their entry to the United States.

In 1987 APHIS created a new division called International Services to manage its Foreign Service and lead on international issues. APHIS FSOs were called on to spearhead technical trade discussions, address technical trade and regulatory issues in international forums; conduct cooperative pest and disease surveys, as well as control and eradication activities; and oversee inspections and clearance of agricultural products in foreign countries. APHIS FSOs were trained in diplomacy and cross-cultural awareness in addition to receiving technical training in plant and animal pests and diseases and how to prevent their spread.

Even as it created its Foreign Service, however, in contrast to other Foreign Service agencies, APHIS remained primarily a domestic-focused agency (with 8,000 Civil Service employees, compared to, at the time, approximately 90 FSOs). The APHIS mission statement reads: APHIS “protects the health of U.S. agriculture and natural resources against invasive pests and diseases, regulates genetically engineered crops, administers the Animal Welfare Act, and helps people and wildlife coexist. APHIS also certifies the health of U.S. agricultural exports and resolves phytosanitary and sanitary issues to open, expand and maintain markets for U.S. plant and animal products.”

APHIS Vienna

A New Foreign Service in Action

Every so often, APHIS’ work is front page news. The foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom in 2001 is one example.

APHIS Vienna

In its first decade, APHIS’ new Foreign Service focused primarily on operational efforts—for instance, building capacity in Haiti and the Dominican Republic to eradicate African swine fever, and advancing screwworm eradication and medfly control. Management and implementation of overseas agriculture product inspection programs were another APHIS priority during this time. Overseas inspection through a “preclearance program,” paid for by foreign government agricultural producers, reduces the risk that a pest or disease will be brought onto U.S. soil. Two large such programs were the Dutch bulb and Chilean fruit preclearance programs. In Chile, the preclearance program is made possible through close collaboration between the U.S. Department of Agriculture/APHIS, the Chilean Agriculture and Livestock Services (SAG) and the Chilean Fruit Export Association (ASOEX). Numerous ambassadors, as well as other embassy staff, have visited APHIS overseas preclearance programs.

By the 1990s, the advent of the World Trade Organization’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary (WTO-SPS) agreement and the North American Free Trade Agreement presaged a shift in emphasis to agricultural diplomacy. The WTO-SPS, in particular, changed the global trade landscape. Gone were the days of elaborate bilateral agreements that were often based as much on politics as on technical merits. For the first time, signatory countries formally agreed that import restrictions and trade requirements “must be based on scientific findings and should be applied only to the extent that they are necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health; they should not unjustifiably discriminate between countries where similar conditions exist.” This did not eliminate the role of politics. It did, however, drive the politics “underground,” making animal and plant health trade negotiations even more nuanced—and the role of the APHIS FSO in sorting out the layers of complexity even more important.

APHIS FSOs became key figures in these new diplomatic arenas, delicately balancing the responsibility of facilitating trade while protecting American agriculture. Using influence and working with like-minded countries, APHIS leadership worked to ensure that the international system governing trade in animals and animal products would be based on the best available science and valid risk assessment. When the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) became the animal health standard-setting organization for WTO-SPS, APHIS helped secure the election of a charismatic and visionary OIE leader. In addition, APHIS successfully advocated for the principle of regionalization, whereby pest- and disease-free zones and regions (instead of geopolitical borders) are recognized for pest and disease control. This allows trade to continue from those zones and regions even if disease is prevalent in a different part of a country. This expanded trade opportunities for U.S. producers but also made import decisions more complicated.

As the 21st century dawned, more trade continued to mean more risk that pest and disease outbreaks might spread to the United States. A vivid illustration was the major 2001 foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom, which devastated farms and livelihoods and cost the public sector more than £3 billion and the private sector more than £5 billion. Working as field veterinarians with their United Kingdom counterparts, APHIS FSOs diagnosed infected herds, supervised humane slaughter of infected animals, and contributed to the effort of directing U.K. farmers to government assistance programs and suicide hotlines—supporting efforts to ensure the disease was eradicated before it spread to the United States.

In 2003, Progressive Farmer magazine—a century-old stalwart in the U.S. agricultural community—saluted APHIS employees, including its FSOs, citing “their vigilant efforts and dedication to protecting U.S. crops and livestock from pests, disease and now bioterrorism” and awarding the agency its prestigious “People of the Year.” It was the first time the publication had given the award to an organization for its service to American agriculture.

As U.S. agriculture developed and changed, new scientific areas have been added to the APHIS FSO’s technical portfolio.

Animal diseases continued to engage APHIS FSOs. In December 2003, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), known colloquially as “mad cow disease,” was detected in the United States for the first time. Despite the fact that all cases detected in the country were either from imported cattle or were determined to be “atypical BSE cases,” and the United States was never categorized as a BSE-affected country, the “cow that stole Christmas” became a focus of national attention. APHIS FSOs worked day and night encouraging other countries to adhere to OIE standards in an effort to ensure safe trade, and thus maintain export markets. The effect on trade, however, was significant. Nearly all export markets for U.S. beef were shut down as a result of largely unjustified measures taken by many countries; and at the tenth anniversary of the first U.S. BSE case, the U.S. Meat Export Federation estimated the cumulative loss in beef trade to be $16 billion. APHIS FSOs would work for nearly another decade to remove all BSE-related restrictions on U.S. exports.

In addition to trade concerns, concerns about the growing threat posed by zoonotic diseases (illnesses that can be transmitted from animals to humans) continued to increase. When an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus occurred in China, Thailand and Vietnam, APHIS directly addressed the virus at its source—in poultry abroad—to reduce the chances of a U.S. outbreak. For example, APHIS FSOs provided training at the APHIS National Veterinary Services Laboratory for 99 foreign officials from 62 countries to conduct avian influenza diagnostic testing as part of capacity building efforts, and APHIS personnel also worked extensively with the White House Homeland Security Council, the Department of Homeland Security and other federal departments and agencies to develop and implement guidelines on how to respond to a potential introduction of HPAI H5N1 in the United States.

And, once again, APHIS took leadership in the international arena. The National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza called for the creation of global partnerships to address pandemic threats. In response, from 2006 to 2008, APHIS used $4.4 million of appropriated funds to support establishment of a global pillar of support to countries that are dealing with an animal disease outbreak—the Crisis Management Centre for Animal Health at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Headquartered in Rome, the CMC-AH, now the Emergency Management Centre for Animal Health, responds to requests from countries to send veterinary teams to provide expert advice. In its first decade, the organization sent 88 technical teams to 45 different countries.

Ambassador Bonnie Jenkins, second from right in the front row, at the FAO Crisis Management Centre Steering Committee meeting in 2016. APHIS worked with FAO to establish the center in 2006; it is now the Emergency Management Centre–Animal Health. The Global Health Security Agenda Presidential Initiative highlighted the importance of APHIS’ role in preventing zoonotic diseases and raised the profile of APHIS’ work.

Courtesy of Karen Sliter

Expanding the FSO Portfolio

Diplomacy has become a central responsibility for APHIS Foreign Service officers under the World Trade Organization’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary agreement and other trade agreements. From left, Mary Lisa Madell, Dr. Jere Dick and Dr. Lisa Ferguson at animal health negotiations within the politically charged and ultimately unsuccessful Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) talks in Brussels in 2014.

APHIS Brussels

To formalize APHIS’ overseas capacity building work, in 2007 APHIS established the International Technical and Regulatory Capacity Building Center as a central entry point and “clearinghouse” for APHIS’ international cooperation / technical assistance activities. APHIS FSOs design training activities, nominate the most qualified participants, and coordinate trainings with international organizations and other countries.

In 2014-2015, when avian influenza entered the U.S. on wild birds and caused our country’s worst animal disease outbreak ever, APHIS FSOs played an instrumental role keeping trading partners informed of our control efforts, promoting confidence in the United States’ ability to ensure safe exports and maintaining critical export markets. By using a “regionalization approach,” exports from unaffected regions continued during the outbreak. And afterward, as with BSE, APHIS FSOs worked for years to recover all the lost markets.

Over the years, as U.S. agriculture developed and changed, new scientific areas have been added to the APHIS FSO’s technical portfolio. Creation of the Biotechnology Regulatory Services program in 2002, for instance, brought increased attention to APHIS’ role in regulating genetically engineered (GE) plants (to ensure they do not pose a pest risk to other plants) and GE products in trade. When a regulated GE plant is found in a shipment of commercial seeds or grain, APHIS FSOs work with foreign counterparts and domestic staff to clarify the risk, if any, and develop mitigations where necessary to keep markets open.

APHIS FSOs can also help their host countries arrange a visit from APHIS’ Wildlife Services experts, for example, to share their expertise in preventing potentially catastrophic bird collisions with airplanes. And well before the COVID-19 outbreak, APHIS FSOs played critical roles within the U.S. government and with OIE, FAO, World Health Organization and the Group of 7 (G7) Global Partnership Against Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction in assisting countries to better prepare for both pandemic and bioterrorism threats.

The APHIS Foreign Service was instrumental in the design of WHO’s Joint External Evaluation tool and process, a voluntary “One Health” country evaluation that assesses pandemic preparedness.

For example, the APHIS Foreign Service was instrumental in the design of WHO’s Joint External Evaluation tool and process, a voluntary “One Health” country evaluation that assesses pandemic preparedness. From 2016 to 2019, more than 100 countries volunteered for a JEE. APHIS’ Foreign Service has been critical to this success. In the process of co-leading seven of the first 11 JEE evaluations globally, APHIS’ Foreign Service documented the process and drafted guidance for both host countries and evaluators to successfully perform the assessments. USDA has used its own JEE results to justify $300 million in funding it recently received under the American Rescue Plan, the 2021 COVID-19 stimulus package. APHIS FSO representation at the G7 Global Partnership Against Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction Biosecurity Working Group brought focus to the risk of plant as well as animal disease bioterrorism and was instrumental in the inclusion of OIE and FAO in these international security fora.

As these new areas developed and increased in importance, two key “historic” aspects of APHIS FSO work overseas were transferred out of Foreign Service management around 2010. The historic screwworm and medfly programs moved to a separate division of International Services; and the preclearance programs transferred to an APHIS domestic unit, Plant Protection and Quarantine.

A poster in Brussels.

APHIS Vienna

The Future of the APHIS Foreign Service

At a livestock market in Ecuador, indigenous Otavalenos women sell caged chickens in 2012. Through its capacity building efforts, APHIS FSOs help countries control diseases before they spread to the U.S., for example, by attending a live bird market training in Ecuador.

Cindy Hopkins / Alamy

On APHIS’ 50th anniversary, its FSOs and domestic staff members face realities that make their jobs ever more vital to the success of American agricultural trade:

• With the globalization of agriculture—a trend that is here to stay—U.S. farmers and ranchers produce more food than U.S. consumers can consume. They need the export markets that APHIS FSOs are so critical in opening and maintaining. Agriculture is a critical component of America’s economic viability.

• More trade equals more risk. Mitigations must be negotiated into trade protocols, and many countries will continue to need APHIS expertise in better controlling pests and diseases.

• Working with other agencies, APHIS will assume an ever more critical role in identifying and controlling zoonotic diseases in animals before they pass to humans.

• Protecting U.S. agriculture has always been a national security issue. APHIS’ ability to respond to a pest or disease outbreak, whether accidental or intentional, is an important component of our nation’s security infrastructure. With both technical and diplomatic expertise, APHIS FSOs must remain engaged in highlevel biosecurity/bioterrorism discussions both within the U.S. government and in groups such as the G7.

• International organizations such as the OIE and United Nations organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization and the International Atomic Energy Agency are vital partners for achieving APHIS’ goals. Active and successful engagement by APHIS FSOs on the multinational level will be critical for influencing trade standards, plant and animal pest and disease control/eradication efforts, and preventing future pandemics.

With so many tasks at hand, however, APHIS FSOs have found that their ability to work proactively, and their influence in international organizations and the interagency space, has been substantially compromised. The number of APHIS FSOs, which for decades ranged between 50 and 60, at one point dropped to below 20 as APHIS struggled to define its vision for the future of its Foreign Service. To rectify the situation, APHIS is now aggressively recruiting and hiring FSOs. Between 2016 and 2020, APHIS recruited a diverse cadre of 22 FSO trainees, retaining 16. APHIS is still recruiting and hopes to welcome additional animal and plant specialists who can join the effort to keep American agriculture and agricultural trade healthy and thriving.

Whether they’ve marshalled the screwworm program through Nicaragua in the middle of a civil war, negotiated critical new market openings for U.S. products, weathered battles with trading partners over bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or advocated the importance of addressing zoonotic diseases in animals to prevent their spread to humans, APHIS’ Foreign Service officers and their domestic colleagues have shown time and again that no matter the challenge, they will find a way forward, protecting U.S. agriculture and promoting science-based agricultural trade.

Read More...

- “Winter in Kabul, 2005,” by Marc Gilkey, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2022

- “Avocado Diplomacy: Supporting Peace in Colombia,” by Marc Gilkey, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2019

- APHIS homepage