Restoring Nuclear Diplomacy

Urgent action is needed to put the lid on a new and costly global arms race.

BY JOSEPH CIRINCIONE

Brian Hubble

The Cold War is over, but the weapons remain. After decades of progress in reducing nuclear arsenals and nuclear threats, the global nuclear security enterprise is close to collapse. Urgent action is needed to save it, including building support for nuclear restraint among both government officials and the American public.

The threat is clear: a new arms race has begun. Each of the nine nuclear-armed nations is building new weapons. Some are replacing older weapons with new generations of missiles, bombers, submarines and warheads. Several (India, Pakistan, China and North Korea) are increasing their stockpiles. Some (the United States, Russia and China) are developing new types of attack systems, including “more usable” weapons.

All nuclear reductions have stopped. Nor are there any new negotiations for future reduction agreements. At best, we have vague talks about talks, or discussions of what conditions might be required before any nation could even consider reducing their nuclear stockpiles.

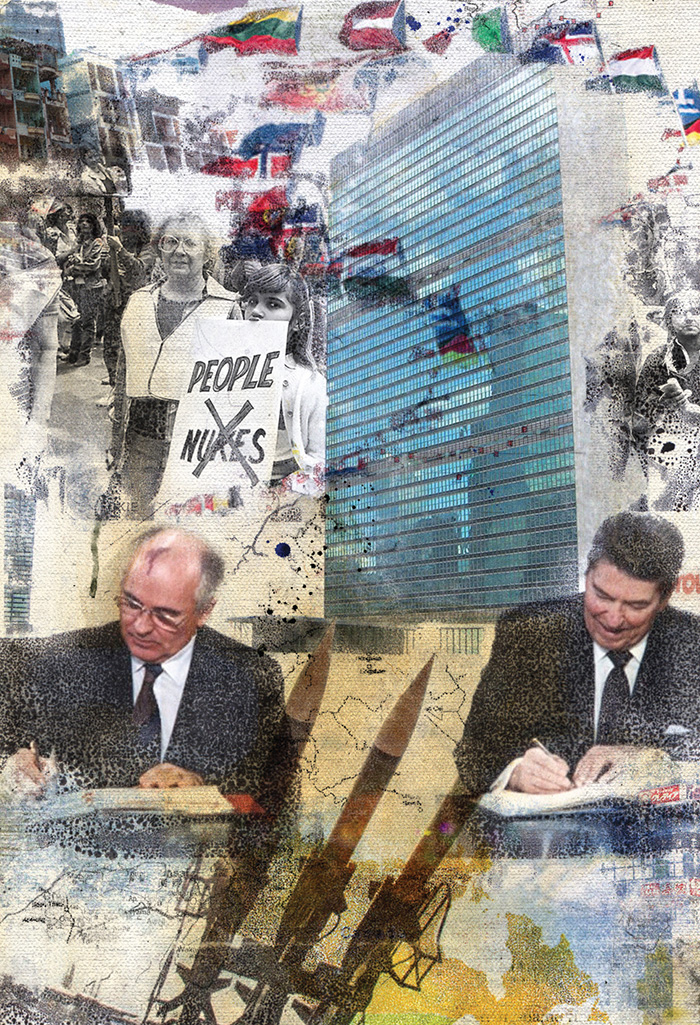

Worse, the security architecture constructed by many nations—and in the United States by both Republicans and Democrats—is being systematically destroyed. The United States and Russia have abandoned the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) negotiated by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev—the treaty that began three decades of disarmament that reduced the global supply of nuclear weapons from more than 66,000 to under 13,500 today.

The last remaining reduction treaty, the 2010 New START agreement negotiated by Presidents Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev, will expire in February 2021. The Trump administration shows little interest in extending the accord. If New START dies, nuclear arsenals will be unconstrained for the first time in 50 years.

Saving the Regime

The collapse of disarmament efforts has provoked strong international reaction. Many non-nuclear nations have issued pleas for the few nuclear-armed states to reconsider their programs and strategies. Other, more assertive actions include the construction of an alternative nuclear security architecture, one organized around a global ban on nuclear weapons, similar to the international bans on biological and chemical weapons and landmines.

On July 7, 2017, 122 nations voted at the United Nations to approve a Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Popularly known as the Ban Treaty, this agreement has since been ratified by 35 nations as of the end of February. When it enjoys ratification by 50 nations, likely before or in 2021, the agreement will become international law.

The collapse of disarmament efforts has provoked strong international reaction.

The treaty is controversial. None of the nuclear-armed states have signed it, and several have come out in strong opposition. Some arms control advocates fear that it would undermine the bargain struck 50 years ago by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT): namely, that those with nuclear weapons would negotiate reductions, and those without these weapons would promise never to build them.

In truth, we need both the vision and practical next steps. When the “Ban Treaty” enters into force, it will provide a noble goal, but not all the steps for achieving that goal. More will be needed to restore nuclear diplomacy.

The First Step

It is still possible that President Donald J. Trump could bring America back to the business of reducing the nuclear threat, even though he ended reductions and led the U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty and the nuclear accord with Iran. After all, Ronald Reagan turned from the massive nuclear buildup of his first term to a second term where his INF Treaty broke the back of the nuclear arms race and began the 30 years of reductions we have enjoyed until the present moment.

President Trump will have a chance to execute such a shift when the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council meet at the United Nations in September in a meeting convened by Russia and announced at the end of February. This meeting could allow the administration to claim progress in involving China in reduction talks and, thus, finally agree to extending the New START Treaty. Trump officials have maintained that the existing treaty is so flawed that it is only worth extending if China becomes a party to the pact and it is extended to including nonstrategic weapons, as well. Although the administration has not done much to advance either of these goals (perhaps because they are not practically achievable), the September meeting could combine with domestic political pressures to convince Trump to extend the treaty. That would be a critical and popular first step.

The treaty enjoys the support of U.S. military leadership because it limits Russian strategic nuclear forces and ensures compliance through robust inspections. General John Hyten, then commander of the U.S. Strategic Command, testified to Congress in March 2017 that he was “a big supporter” of the New START Treaty, and that “bilateral, verifiable arms control agreements are essential” in providing an effective deterrence structure. Admiral Charles Richards, who now leads the Strategic Command, testified on Feb. 27 that he, too, supports the treaty.

Global leaders would welcome the move. “Russia has indicated, at the highest levels, its willingness to do so,” explained former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and former Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov in a rare joint New York Times op-ed. “The United States and Russia can avoid a senseless and dangerous return to nuclear brinksmanship if they act soon. There is no reason to wait, and extending the treaty, known as New START, is the place to begin.” They were supported by a concurrent joint statement from 29 former foreign ministers who warned of a “rapidly deteriorating nuclear landscape and the increasing possibility of nuclear weapons being used either deliberately or through an unintended escalation.”

Stopping the Arms Race

The second step, either by Trump or the next U.S. president, is more difficult, though no less important: We must contain the massive new nuclear weapons programs now underway before they lock in another 40 years of nuclear brinksmanship. In the United States, these programs are the legacy of the Obama administration, which agreed to an $88 billion “nuclear modernization” program to secure Republican backing of the New START Treaty in 2010.

There was then, and remains still, bipartisan support for the reasonable updating of older weapons and infrastructure. President Obama himself articulated this point when he declared in Prague in 2009 that “as long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal.”

However, there is no bipartisan consensus for an indefinite arms race. It was assumed that reasonable modernization programs would go hand-in-hand with continued arms control. Obama and Medvedev saw New START as a quick fix to preserve verification mechanisms and implement some small reductions while they negotiated a new treaty for truly deep cuts in the arsenals. Thus, steady reductions would allow them to maintain nuclear forces at safer and less expensive levels than before. That bargain has been broken. A combination of Republican political opposition, Russian recalcitrance and stiff resistance from inside the nuclear-industrial complex blocked further cuts. Arms control stopped, yet the contracts continued.

Nuclear diplomacy cannot be restored by traditional means alone. There must be a nonpartisan counter to the allure of defense contracts.

“Experts are suddenly talking less about the means for deterring nuclear conflict than about developing weapons that could be used for offensive purposes,” warn Albright and Ivanov. “Some have even embraced the folly that a nuclear war can be won.” The Russian deployment of shorter-range nuclear-capable missiles in Europe and U.S. deployment on strategic submarines of new “low-yield” nuclear warheads are cases in point.

The resources devoted to this new nuclear buildup are staggering. Nuclear-armed states will spend more than $1 trillion this decade on nuclear weapons. The United States will spend the most, more than all the other nations combined. The Trump administration’s budget for Fiscal Year 2021 allocates more than $50 billion for new weapons, more than at any time since the end of the Cold War. This is a small part of the $2 trillion these weapons will cost American taxpayers over the next 25 years.

If these programs are not reined in soon, they may become unstoppable. Once contractors start “bending metal,” as my colleague William Hartung said recently, these programs become much harder to cancel. Defense contractors spread production across the country, creating political support for programs in the Pentagon and Congress.

Reorienting National Priorities

That is why the third step may be the most consequential. Nuclear diplomacy cannot be restored by traditional means alone. There must be a nonpartisan counter to the allure of defense contracts.

On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City’s Central Park, protesting the Cold War arms race. It was the largest political demonstration in American history; and, coupled with a nuclear freeze movement, it challenged the U.S. and Soviet leadership to reverse their nuclear buildups.

Although President Reagan resisted the anti-nuclear movement fiercely—at one time claiming it was the work of “foreign agents”—he soon understood that the political ground had shifted. It may have also allowed him to get in touch with his own deeply held feelings about abolishing nuclear weapons. He began declaring publicly that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” and pressed his Cabinet to find diplomatic openings with Moscow.

“If things get hotter and hotter, and arms control remains an issue,” Reagan told his secretary of State, George Shultz, in late 1983, “maybe I should go see [Soviet leader Yuri] Andropov and propose eliminating all nuclear weapons.” Two years later, he found a partner in Mikhail Gorbachev and by the end of the decade had powerfully reversed the nuclear arms race.

We cannot expect to replicate the 20th-century nuclear freeze movement. Instead, the challenge will be to fold this issue into the new, vibrant mass movements of the current era. It may be possible for arms control and disarmament advocates to partner with movements on climate action or health care, for example. These social changes will need massive government funding for new programs. The nuclear budget is one major source for those funds. And, as important as these other causes are, they cannot achieve their goals if nuclear catastrophe occurs. If these movements can connect and reinforce each other, awareness of how the issues intersect will grow, and Washington may again be convinced that effective diplomacy will pay domestic political dividends.

It may be that the COVID-19 pandemic will reorient national priorities, alerting us to the danger of ignoring growing catastrophic threats. There may be a new opening to restore nuclear diplomacy, to think anew and to offer clear, practical steps to prevent the worst from happening—before it is too late.