Counterinsurgency in Vietnam: Lessons for Today

Forty years later, the experience still offers valuable insights for effective expeditionary diplomacy.

BY RUFUS PHILLIPS

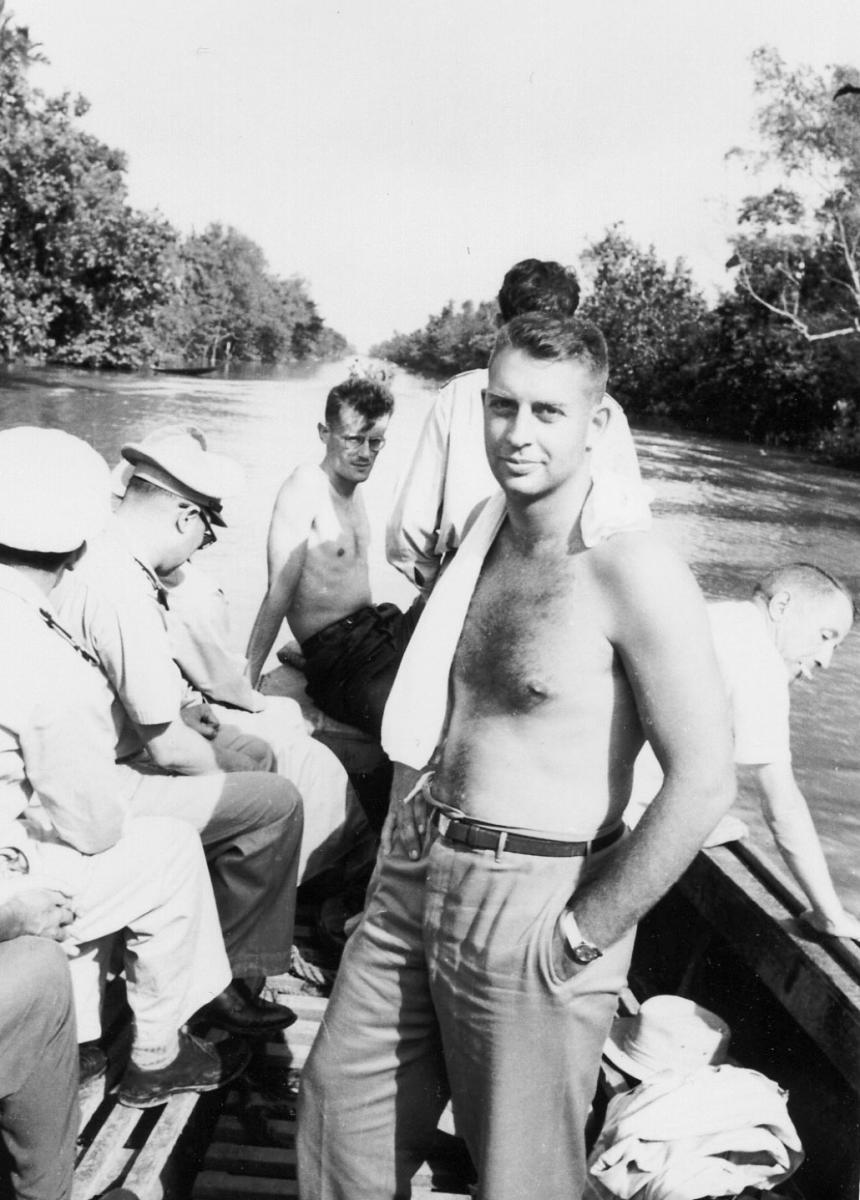

Rufus Phillips on a 1954 inspection trip to a formerly Viet Minh-controlled area in the Mekong Delta recently handed over to the South Vietnamese Army.

Courtesy of Rufus Phillips

There are lessons to be learned from our counterinsurgency efforts in Vietnam that remain relevant today.

Chief among them is this: although our understanding and steadfast support can make a significant difference, ultimate success depends on the people we are assisting. Likewise, our insufficient and often mistaken grasp of the insurgent enemy and the cultural and political context of the involved country and its people can greatly contribute to failure. These precepts sound simple, but they are often overlooked because we are so focused on ourselves.

Another lesson is that counterinsurgency works when politics and development are as much a focus as security. For lasting effect, counterinsurgency cannot be divorced from political reform and progress from the top down, as well as from the community level up, of the country we are helping. The active support of a majority of the country’s population for its government is critical. Countering insurgencies by establishing security through military and police operations is a necessary precondition for political progress, but only indigenous governments that become responsive to their own people can ensure that security endures.

Counterinsurgency in Vietnam went through various phases in terms of what it meant, how it was carried out and how the United States helped or hindered. Understanding the lessons that experience holds for today requires some history.

Early Efforts

Counterinsurgency actually began in Vietnam during the Indochina War (1946-1954) and was known as “pacification.” The French created military-civilian teams (called équipes mobiles), which performed civil functions in conjunction with military operations aimed at establishing French control over areas dominated by the communist Viet Minh. Such efforts were fatally undermined, however, by French unwillingness to give the noncommunist Vietnamese real independence—the prime political cause motivating all Vietnamese.

In the 1954-1955 post-Geneva Accords era, Ngo Dinh Diem emerged as the person who finally achieved complete independence, overthrowing Emperor Bao Dai and establishing the Republic of Vietnam. This gained him widespread support. Underpinning that was a reformed and motivated South Vietnamese army with a positive set of civic action–oriented attitudes toward the civilian population. This ethos earned popular support while defeating sectarian insurgencies, and began to wean villagers’ allegiance away from the Viet Minh. The approach owed much to Edward G. Lansdale’s advice, based on his involvement in Ramon Magsaysay’s successful campaign against the communist Huks in the Philippines and election as president with an overwhelming popular mandate.

The United States did not support the Diem government’s effort to reach the rural population by sending civilian civic action teams into the villages until it was too late.

Once firmly in power, however, Diem made political errors that were compounded by U.S. mistakes. Most prominent was our decision to take the Vietnamese Army entirely out of the internal security role it had played and convert it into a conventional regular army—trained, organized into corps and divisions, and equipped to confront an overt North Vietnamese invasion (which would not occur for another 20 years).

Despite clear evidence that the North intended to revive its earlier rural-based insurgency, a poorly trained, inadequately equipped Civil Guard took over rural security, supported under the U.S. aid program by a Michigan State University contract team consisting mainly of retired U.S. police officials as advisers. The United States did not support the Diem government’s effort to reach the rural population by sending civilian civic action teams into the villages until it was too late.

1961-1963: The Kennedy Era and Rural Affairs

In 1961, when faced with possible South Vietnamese collapse caused by a revived Hanoi-directed insurgency, the John F. Kennedy administration decided to take a stand in Vietnam against further communist expansion in Asia. The watchword was counterinsurgency, but at higher official levels the mission was understood more as a traditional military combat approach with an overlay of Special Forces than as an effort to address the security, political and economic sides of the conflict where it mattered most—at the village level. American military advisers were inserted at all Vietnamese army levels down to the provinces. Initial CIA efforts supported irregular defense forces among the mountain tribes (e.g., the Montagnards) and other home-grown sources of popular resistance to the Viet Cong.

In 1962, following an onsite study of how to get USAID involved in counterinsurgency, the Saigon aid mission was reorganized, with a new special office called Rural Affairs that assigned representatives to each province. (At the time, only three of the aid mission’s American staff of 110 were posted outside of Saigon.) The study found that the Vietnamese were implementing their own counterinsurgency approach, the Strategic Hamlet Program—at heart a self-defense, self-government effort focused on the smallest rural settlement, the hamlet. After initial progress, however, the program was stalling; the overly centralized Vietnamese bureaucracy was a significant impediment. Also, the population relocation focus the program started with (based on the British Malaya experience) was ill-suited for Vietnam, where the insurgency was not primarily defined along ethnic lines.

Impressed by civic action deeds, Central Vietnam villagers who had been under Viet Minh control for nine years welcome Vietnamese Army troops in 1955.

Courtesy of Rufus Phillips

The United States injected the local currency equivalent of $10 million into the hamlet program. Joint Vietnamese-American committees, consisting of the province chief, the Rural Affairs civilian representative and the U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam military adviser, made spending decisions at the provincial level on a consensus basis. The aid supported various self-defense and self-development programs, ranging from hamlet physical improvements, elections and training for elected officials to hamlet defense militia. Though the USAID provincial representatives had minimum assignments of two years, U.S. military advisers were limited to one-year tours with no extensions, which handicapped their effectiveness.

Hamlet elections encouraged political participation, while the self-help projects—carried out with government-provided materials but using local labor—brought visible physical improvements. Accelerated agricultural and livestock development programs improved farm incomes, often for the poorest villagers. In fact, for the first time since the insurgency began seriously in 1959, South Vietnam produced a rice surplus for export in 1963.

In 1962 the Saigon aid mission was reorganized, with a new special office called Rural Affairs that assigned representatives to each province.

Rural Affairs also had the flexibility to fund and provide advisers for a surrender program called Chieu Hoi. This program filled a gap in the initial counterinsurgency approach and began attracting defections from the insurgency. Notable among the Rural Affairs provincial representatives were two Foreign Service officers on their first overseas assignment, Richard Holbrooke and Vladimir Lehovich. They were the expeditionary diplomats of that time and the precursors of much greater State civilian involvement in what was to become the Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support program, or CORDS.

While U.S. provincial military advisers strongly supported the local self-development and self-defense program, at upper echelons MACV focused on conventional warfare. The Vietnamese army was advised to undertake large unit sweeps, which often turned up empty-handed as Viet Cong units melted away. This mistake was compounded by the overuse of airpower to attack villages and by blind artillery fire into predetermined areas thought to harbor Viet Cong.

With the exception of one province, where a Vietnamese army regiment was permanently stationed and provided back-up support for the hamlet program, the war was being fought on two different levels. One was local, through the hamlet program aimed at protecting and winning over the civilian population. At most regular Vietnamese army unit levels, however, the main objective was to win the war by killing Viet Cong (with insufficient concern about the adverse effects of such tactics on the civilian population).

A strategic hamlet school constructed by local self-help groups in 1963.

Courtesy of Rufus Phillips

1964-1966: Mistakes, Confusion and Decline

The U.S.-supported coup against President Diem on Nov. 1, 1963, brought progress to a crashing halt. The generals leading the coup were initially opposed to continuing the hamlet program. At the same time, almost all province chiefs, good and bad, were replaced; and most paramilitary units providing outside-the-hamlet security were disbanded. Meanwhile, the Viet Cong had already begun a concerted campaign to destroy the hamlet system, particularly in the Mekong Delta, where it was overextended and most vulnerable.

When the junta finally agreed to continue the hamlet effort under a different name, another coup occurred, encouraged by American impatience because the generals were slow to get organized. Now that one person—the new coup leader, General Nguyen Khanh—seemed to be in charge, U.S. officials believed that the war would suddenly be prosecuted with renewed focus and energy.

Instead, Khanh’s attempts at one-man-rule backfired; political chaos ensued, and military cohesion declined. The absence of an acceptable Vietnamese political way forward undermined everything else, not the least the effort to counter the insurgency. Compounding the confusion, a new USAID mission director decided that much of the Rural Affairs program was wrong. He abolished the joint provincial committees and returned decision-making to Saigon. Just when direct funding of counterinsurgency at the provincial level was most needed, it was largely cut off by our own actions.

The U.S.-supported coup against President Diem on Nov. 1, 1963, brought progress to a crashing halt.

Chaos continued into 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson sent in U.S. combat troops to counter the insertion of regular North Vietnamese units that threatened to divide the country in half. The character of the conflict changed when responsibility for winning was taken over by the United States. We were going to win the war militarily, then give the country back to the Vietnamese. There was a refocus on counterinsurgency after Henry Cabot Lodge returned as ambassador in mid-1965, but it received mainly lip service from General William Westmoreland, the MACV commander. Lodge brought out Ed Lansdale to coordinate counterinsurgency; but lacking Lodge’s strong backing, he was undermined by the various U.S. civilian agencies and MACV.

Each agency ran its own counterinsurgency program until the end of 1966, when a combined civilian effort was attempted. Called the Office of Civil Operations and directed by Deputy Ambassador William Porter, it too failed. Finally, after a pitched interagency battle in Washington in which President Johnson’s special assistant for Vietnam, Robert Komer, prevailed, U.S. counterinsurgency was put directly under MACV.

1967-1973: CORDS

In late 1967, for the first time, American support for Vietnamese counterinsurgency became a fully integrated military and civilian effort. Komer was sent to Saigon to head the new Office of Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support, created as a separate MACV command whose civilian chief was answerable directly to General Westmoreland. As the Vietnamese government under Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky and then President Nguyen Van Thieu consolidated itself, it was reorganized to give prime importance and support to counterinsurgency. This provided a Vietnamese counterpart for CORDS.

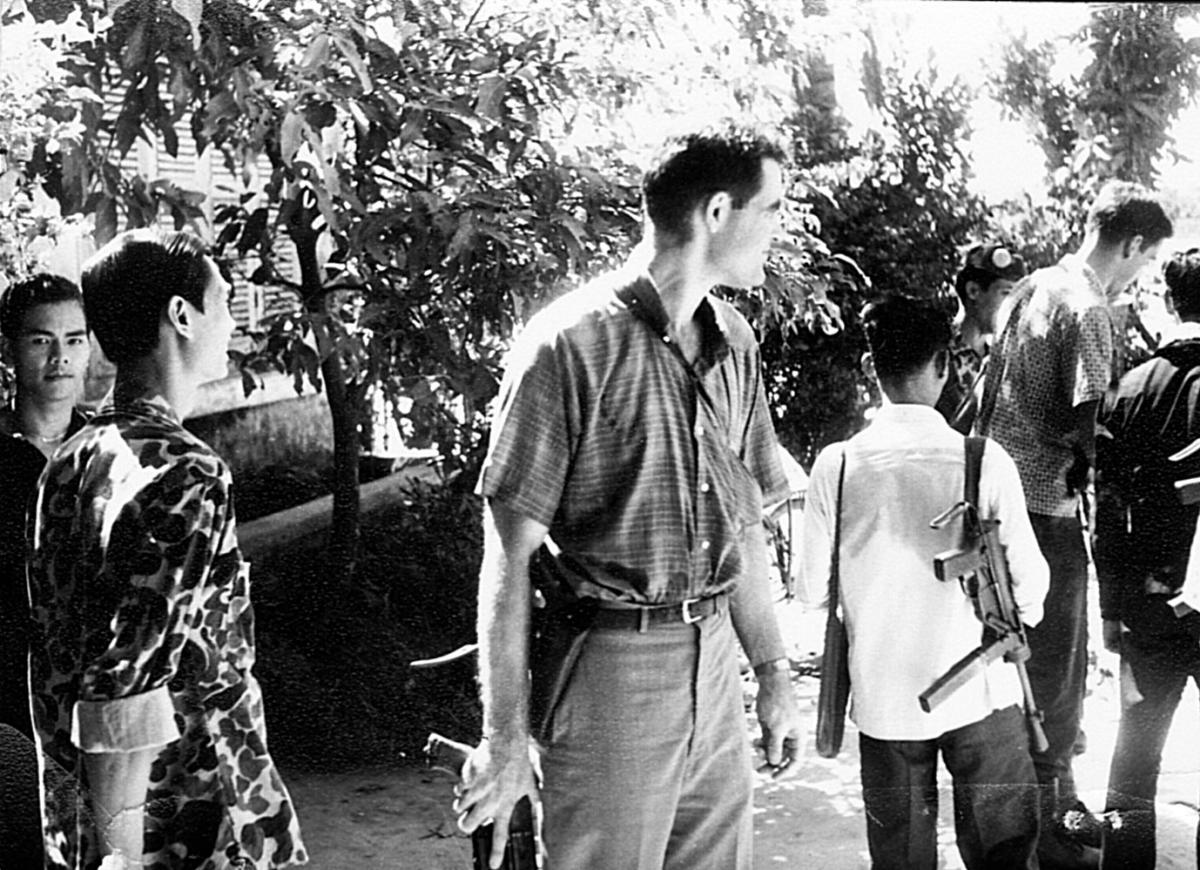

FSO Doug Ramsey (center) and USIS FSO Frank Scotton (right). In 1966, as a USAID provincial representative in Hau Nghia, Ramsey was captured by the Viet Cong and held in the jungle under unspeakable conditions for seven years.

Courtesy of Bruce Kinsey

Ironically, the 1968 Viet Cong Tet Offensive, which undermined American public support for the war, opened the way for CORDS-supported counterinsurgency success. Generally regarded in the United States as a victory for the North, the offensive was actually a spectacular setback in the insurgents’ ability to continue controlling the Vietnamese countryside. They lost most of their best political cadre and fighting units in Tet and several subsequent smaller campaigns called “mini-Tet,” and significant segments of the population mobilized against them. The nature of American military leadership also changed with the June 1968 replacement of General Westmoreland by General Creighton Abrams, who strongly supported counterinsurgency.

The CORDS civil-military advisory effort extended all the way down to the district level in the provinces. Integrated CORDS advisory missions, involving USAID, MACV, Joint United States Public Affairs Office (United States Information Service) and CIA officials, were stationed at regional (corps) and provincial levels, with smaller advisory teams at the district level. The four regional offices were commanded by senior military personnel, with one exception: John Paul Vann, a USAID civilian employee (and former military officer). At provincial levels, depending on security conditions, CORDS was headed by a civilian or a military officer. By 1969, the American advisory force in CORDS had grown to a total of about 7,500—consisting of 1,100 civilian and 6,400 military advisers. Of the latter, about 5,800 served in the field and the remainder in Saigon and regional offices.

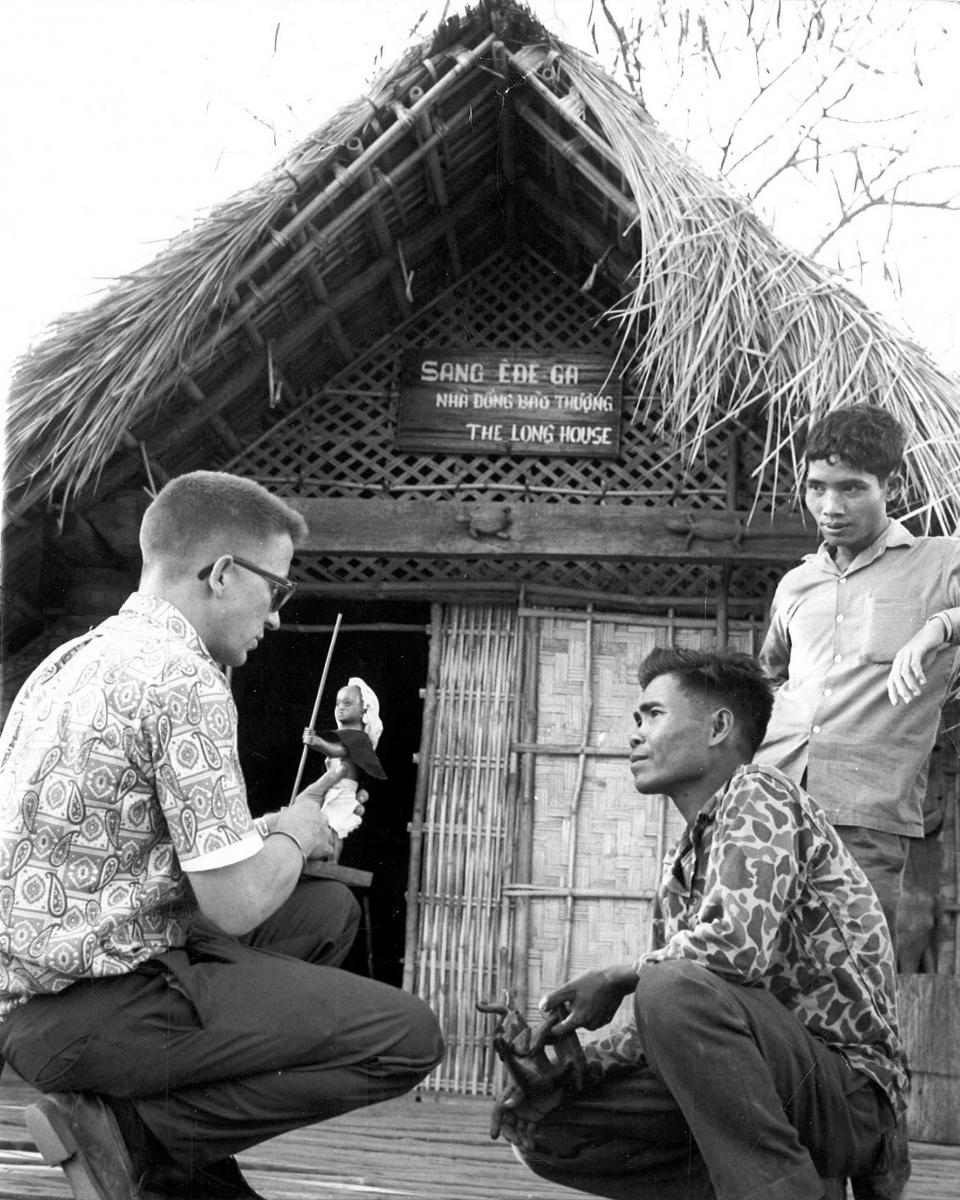

CORDS representative Mike Benge at the 1967 opening of a Montagnard handicrafts center he helped create. Captured during the 1968 Tet Offensive, he managed to survive until released in 1973. He received Prisoner of War and Purple Heart medals from USAID in 2013.

Courtesy of Rufus Phillips

Although Bob Komer had performed splendidly in organizing CORDS and getting it started in late 1967, his bombastic manner alienated the Vietnamese and angered Gen. Abrams. He was replaced in early 1969 by his deputy, William Colby, who knew how to work with the Vietnamese and ran CORDS in a very open, low-key but effective manner. Backed by Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, Colby dealt directly with host-government officials at all levels, from Pres. Thieu on down, on counterinsurgency matters. This helped avoid misunderstandings and improved implementation. He was able to bring trusted and independent information and political judgment to bear at higher command levels, where it counted. No such across-the-board access had existed since the original Rural Affairs operation in 1962-1963.

In 1969 CORDS began supporting a series of nationwide counterinsurgency plans in what was called an “Accelerated Pacification Campaign.” Province-by-province plans prepared with Vietnamese participation called for the gradual extension of control outward from hamlets already supporting the government into areas under Viet Cong influence, while postponing contesting areas under complete Viet Cong dominance. A Vietnamese government decision to treat local security force service as a substitute for the regular military draft encouraged a rapid increase in local defense forces. Counterinsurgency effectiveness was further enhanced by the extension of more local self-government (e.g., elections for village chiefs and councils and for provincial councils).

Equipped with its own funds, CORDS injected supplementary funding at the local level, adding to the larger volume of funds flowing through Vietnamese government channels on a decentralized basis. Rural development programs launched by Rural Affairs were accelerated, and new ones were added. Despite the Thieu government’s drawbacks—too much corruption and a lack of openness and political legitimacy—counterinsurgency was strongly backed from the top. Such government actions as fully implementing land reform had a beneficial political effect, particularly in the Delta.

In late 1967, for the first time, American support for Vietnamese counterinsurgency became a fully integrated military and civilian effort.

CORDS also supported an intelligence and armed action program directed at the local Viet Cong infrastructure. Originated by the South Vietnamese, it became known as “Phoenix.” Armed provincial teams conducted raids against the local insurgency to remove its members from the battlefield by capture, if possible. CORDS advisory instructions clearly emphasized capture, to gain intelligence. While excesses did occur, the program acquired a bad reputation in the United States based largely on unsubstantiated congressional testimony. North Vietnamese comments after the war would give considerable credit to Phoenix for obliging local Viet Cong political and military cadre to move to neighboring Cambodia.

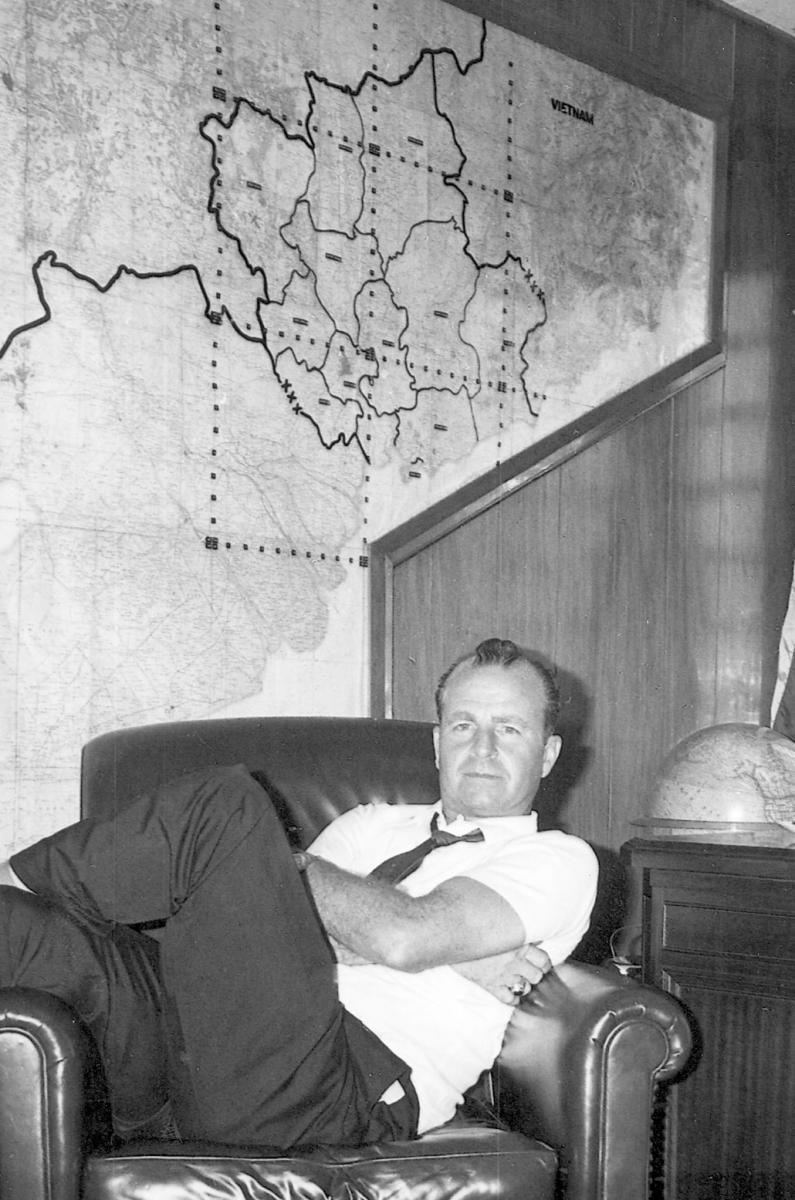

John Paul Vann, the legendary USAID provincial representative who rose as a civilian to become the top CORDS officer in charge of the II Corps region, died in a helicopter crash in 1973.

Courtesy of Ogden Williams

As CORDS grew, its American advisory personnel were becoming better prepared. A counterinsurgency training center, originally set up in 1964 in Hawaii by USAID, was moved to Washington to train CORDS advisers. Between 1968 and 1973, the Vietnam Training Center turned out 1,845 mostly civilian advisers from State, USAID and the CIA, of which about 250 became Vietnamese speakers. Instruction consisted of a mandatory 10 weeks in the role of an adviser, counterinsurgency concepts, development programs and familiarity with Vietnamese culture, history and language. Some trainees continued with intensive language for up to a year. Center graduates added significantly to CORDS success.

By 1972, counterinsurgency had succeeded in pacifying most of South Vietnam with the indispensable and strong support of CORDS. At the time, the CORDS program did not get the recognition it deserved. After the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, instead of a measured transition to full South Vietnamese control, CORDS support was precipitously withdrawn.

Two years later, when, in the absence of U.S. logistical or air support, South Vietnam collapsed in the face of an all-out conventional invasion by the entire North Vietnamese Army, the CORDS story was buried in the rubble—not to be revived until after 9/11.

Conclusions

Lessons learned from the overall experience, involving both sides of the U.S.-Vietnamese relationship, apply to many fragile countries currently under internal extremist threat.

Some have concluded from CORDS that complete U.S. unity of command is necessary for counterinsurgency assistance to be effective. However, at the probably less-intense scale of continuing U.S. involvement in an advisory capacity to fragile states dealing with incipient and existing insurgencies, what is most essential is civilian-military unity of strategy and effort. This can be achieved if both the civilian and military sides are equally geared up to work together, which puts a premium on skilled civilian participation from the State Department.

Effective service of this kind requires personal capability and specialized training including language, as well as being able to operate more freely in dangerous environments than present security rules allow. This is a large part of why State needs to create a relatively small group of highly trained expeditionary diplomats.

As CORDS grew, its American advisory personnel were becoming better prepared.

They would not only help U.S. mission chiefs manage the political and development sides of stabilization efforts in vulnerable states, but coordinate our counterinsurgency advisory efforts, as well. The continuing contest with extremists over the political and security stability of such states requires a longer-term and more focused approach.

In this context, some useful lessons can be drawn from the Vietnam counterinsurgency experience:

• Counterinsurgency cannot succeed without a political strategy which leads to the host country’s government gaining the strong support of its own people. This support is critical to long-term stability and cannot be imposed from the top down, but must be earned by deeds that are basically democratic in nature.

Left to right, Dick Holbrooke, Bob Komer (head of CORDS), Dick’s brother, Andy, then in the Army, and Vlad Lehovich, in Nha Trang in 1967.

Courtesy of Vlad Lehovich

• Security is essential for political stability; but without political progress, security will not endure. For the United States, carrying out an effective political strategy with skilled civilian advisory assistance, as well as wise, effective military advice, can be critical.

• Protection of the population (as stressed in the current U.S. armed forces counterinsurgency manual) and winning its support is necessary for success. Although only indigenous governments can ultimately win this kind of struggle, well-informed and wise U.S. support and advice can be essential.

• Success in providing effective help for host-government counterinsurgency is proportional to the amount of mental effort devoted by us to understanding the nature of the country, the aspirations of its people and the insurgent enemy.

After the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, instead of a measured transition to full South Vietnamese control, CORDS support was precipitously withdrawn.

• A completely integrated U.S. civilian-military advisory effort is ideal. However, in the current and probable future circumstances of less massive U.S. interventions, our counterinsurgency support needs to be a collegial venture marked by close interagency cooperation with a combined political, military and development focus. There also needs to be an effective organizational focus on the host government side.

• The CORDS effort succeeded to the extent it did not because of its size (which at times was an encumbrance) but because of its most dedicated and knowledgeable participants. Skilled individuals count much more than numbers.

• To be effective, counterinsurgency has to be built by the host government and citizens from the community level up, while simultaneously strongly supported from the top down. This often runs up against overcentralized authority and control.

• Attitudes of respect for the civilian population and a genuine devotion to their well-being on the part of indigenous government military and civilian officials at all levels are extremely important. The United States needs to play a strong role in insisting on this approach as part of our assistance.

In dealing with incipient and existing insurgencies, what is most essential is civilian-military unity of strategy and effort.

• Most U.S civilian and military advisers involved in counterinsurgency and stability assistance, to be fully effective in the host country, need specialized training, language capability and longer than conventional periods of assignment. Our support is not likely to be successful unless we have some advisers out in the field, despite the security risks involved.

Finally, intertwined as it is with political progress in enlisting the willing support of the population, counterinsurgency is a long-term process requiring dedication, patience and persistence. After all, we are talking about changing people’s minds.

Read More...

- Why Vietnam Matters, Rufus Phillips (www.whyvietnammatters.com)

- Three Lessons from Vietnam (The Washington Post, Dec. 29, 2005)

- Counterinsurgency in Vietnam: Lessons Learned, Ignored, then Revived (Small Wars Journal, 2008)

- The Picture Awaits: The Birth of Modern Counterinsurgency (World Affairs, 2009)

- A Legacy of Vietnam: Lessons from CORDS (The Simons Center)

- Impact of Pacification in South Vietnam (RAND Corporation, 1970)