From Whitehouse to the White House

From the vantage point of both the field and the National Security Council, one FSO shows the critical role the Foreign Service played in a difficult environment.

BY KENNETH M. QUINN

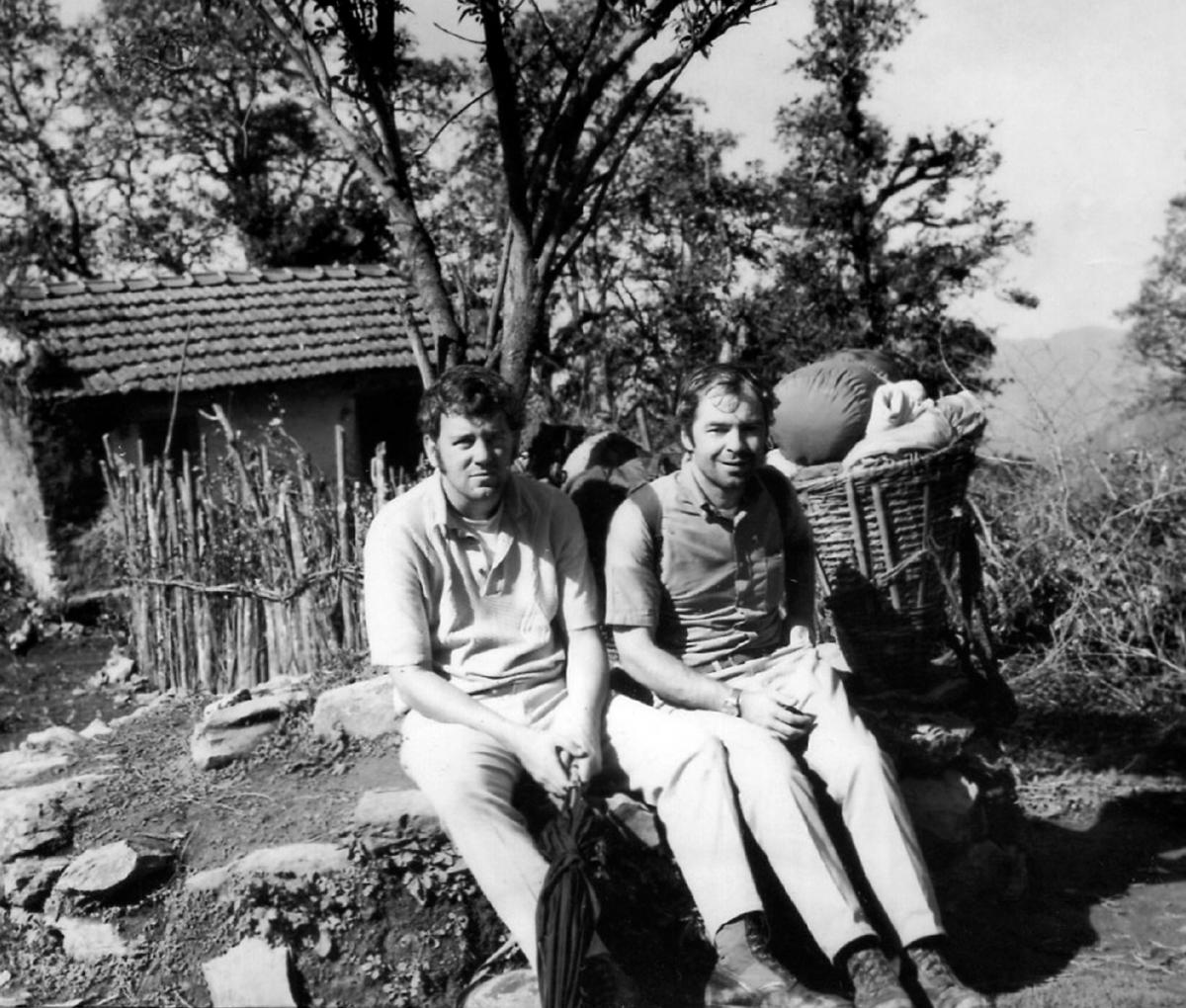

The author with Kent Paxton, right, a USAID officer who was instrumental in shepherding the very first refugees arriving in the United States through the U.S. Air Force base outside of San Francisco. He used his own money to purchase tickets for families of FSOs, as there was no system in place to deal with them.

Courtesy of Kenneth Quinn

It would be difficult to overstate the pure joy exhibited by my Vietnamese employees on Advisory Team 65 in Chau Doc province, in a remote corner of the Mekong Delta, on Jan. 27, 1973, when word reached us that the Paris Peace Accords had been signed. Holding hands, they danced in a circle singing “Hoa Binh oi”—loosely translated, “Hello, peace!” or “Welcome, peace!”

None of them likely could have imagined that, just two short years later, the South Vietnamese government would collapse and many of them would be fleeing down the Mekong River, hoping to escape the approaching North Vietnamese Army.

In 1973 I was a rural development adviser on my fourth consecutive tour in Vietnam. I’d been seconded by State to the U.S. Agency for International Development in 1967, right after completing the A-100 orientation course. All of my time “in country” had been as part of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam’s Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support program, known as CORDS, part of the unified military-civilian chain of command of the pacification effort. That would now change dramatically, as the U.S. military prepared to completely leave the country and the State Department established four consulates general, including one in Can Tho, the largest city in the Mekong Delta.

It also began a personal odyssey that would allow me, first, to be part of what I call the “Whitehouse Interlude” in Vietnam, a brief but remarkable period in Foreign Service history that deserves to be recalled with considerable pride. This would be followed by a front-row seat at the White House in Washington to the tragic denouement of the South Vietnamese government and America’s epic involvement in Indochina.

I believe that the provincial assignments had a significant impact on many of the FSOs who would shape foreign policy over the next three decades, as they came in direct contact with large numbers of war victims. For example, I always felt that Ambassador Richard Holbrooke’s passion to alleviate the suffering of refugees and his focus on agriculture in Afghanistan both came from his assignment as a provincial adviser in Vietnam. Indeed, the very existence of the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration in the State Department can be traced to Vietnam.

Our work there also showed that the Foreign Service could be an invaluable early warning system. In my own case, a decade after writing the first-ever reports on the genocidal nature of the Khmer Rouge, my “provincial instincts” took me in 1983 to the far north of Lebanon where I discovered Yasser Arafat reconstituting his PLO military forces outside Tripoli. After 9/11, I wondered whether we might have detected the plans of Osama bin Laden to strike the United States if we had had more FSOs able to travel through remote parts of South Asia and the Middle East, in the way we did in Vietnam.

The Whitehouse Interlude

With the departure of Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker after the 1973 Paris Peace Accords were signed, Deputy Chief of Mission Charles Whitehouse became chargé d’affaires and ushered in a spirit of openness and unvarnished reporting. This was reinforced by two Vietnam veterans, Tom Barnes and Frank Wisner, who arrived in Can Tho as the new consul general and deputy principal officer, respectively. They were followed by a flood of mid-level, language-trained FSOs, one in each of the 16 provinces in the Delta, augmented in many cases by Vietnamese-speaking USAID officers. Similar assignments followed in all 44 provinces of South Vietnam.

This “diplomatic surge” produced an amazing body of reporting documenting the shaky security situation and warning of what was to come. Seldom has the Foreign Service fielded so many highly competent individuals in such a dangerous but critically important environment.

Seldom has the Foreign Service fielded so many highly competent individuals in such a dangerous but critically important environment.

For my part, I continued to live and work in the provincial capital of Chau Doc, at the juncture of the Mekong River and Cambodian border. Now a vice consul, I had remarkable experiences during my 15 months there. Besides reporting on Pol Pot‘s Khmer Rouge, I used a plane and pilot for a week to map the extent of Viet Cong control of the entire Mekong Delta. I also burrowed into the dirt as bullets cracked over my head when a North Vietnamese Army unit, in a major ceasefire violation, ambushed an American cargo ship I was monitoring on the Mekong River.

My Vietnam assignment came to an abrupt end in April 1974 when an Air America plane landed in Chau Doc with orders transferring me to the National Security Council staff. My move from obscurity to a job at the White House caused quite a stir in Saigon. Suddenly I had appointments at the embassy, including with Ambassador Graham Martin and Tom Polgar, the Central Intelligence Agency’s chief of station.

While Amb. Martin was gracious to me (he even came to my wedding, which took place a few days before I departed the country), I found my one-on-one meeting with him somewhat disquieting. At times, he seemed to drift away in thought during our conversation. Leaning back in his chair and staring at the ceiling, he waxed philosophical about the vagaries of the policy process and the forces that were undermining him.

At the White House: Watergate

Arriving in May 1974, I found the White House beset by the issue that would ultimately play a very significant part in the demise of South Vietnam: Watergate. Less than three months later, I would be standing in the East Room watching Richard Nixon give his farewell address to the nation. Vice President Gerald Ford would inherit a weakened presidency that would be unable to respond forcefully a year later as South Vietnam collapsed.

Still, the military situation remained relatively stable through the rest of that year and into early 1975. There were intelligence reports that the North planned to step up military action in the central highlands in the spring, but the conventional wisdom was that Hanoi would wait another year so as to influence the 1976 U.S. presidential election. Indeed, the view in Saigon was so sanguine that Amb. Martin returned to the United States for dental work and consultations in March 1975.

Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger’s office on the night of the Mayaguez rescue, May 14, 1975. Kenneth Quinn is on the left, Kissinger in the center and Deputy National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft at right.

Courtesy of Kenneth Quinn

It was therefore stunning when the initial forays by NVA units in Ban Me Thuot province on March 10, 1975, quickly inflicted severe defeats on South Vietnam’s 22nd and 23rd divisions—the latter considered one of the better-led units. Now able to mass their forces without fear of punishing U.S. air strikes, the North rained down overwhelming firepower onto the South Vietnamese positions. By mid-March, having secured control of the entire highland area, their attention turned to Da Nang, the major military headquarters in central Vietnam, where the same process began to unfold.

By March 25, the deterioration was so alarming that Pres. Ford held an emergency meeting in the Cabinet Room at the White House with a senior emissary from South Vietnam, labor leader Truong Quoc Buu. I had the extraordinary opportunity to be the president’s interpreter as Buu revealed President Nguyen Van Thieu’s shocking plan to cede the entire northern half of South Vietnam to the communists.

The Weyand Mission: Return to Saigon

Immediately thereafter, the White House announced a presidential mission to Vietnam, headed by General Fred Weyand, the previous commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, to assess the situation. I was assigned to the trip. Traveling with Weyand and several senior CIA and Pentagon officials on his C-141 cargo plane were Amb. Martin and David Kennerly, Pres. Ford’s personal photographer and a Pulitzer Prize-winning combat journalist, with whom I had developed a friendship.

When we arrived at the darkened Tan Son Nhut Airport just after midnight on March 28, 1975, the atmosphere already felt ominous. I had a brief exchange on the tarmac with Station Chief Tom Polgar, who privately expressed his concern that the ambassador, who had consistently downplayed field assessments as too negative, would not report on how calamitous the situation had become.

Amb. Martin invited me to stay at his residence. During the week we were there, I found a sense of impending doom. Members of his Vietnamese household staff approached me, almost in tears, asking if they would be taken out of the country when the end came. Even Mrs. Martin appealed to me privately for guidance about what to tell her employees, with the clear implication that her husband was not giving her sufficient direction.

Kenneth Quinn meets with President Gerald Ford in January 1977.

Courtesy of Kenneth Quinn

While Gen. Weyand and his most senior advisers called on Pres. Thieu and the top military echelon of the South Vietnamese government, I went off on my own about the city talking to Vietnamese contacts and assessing the mood. I learned a lot just watching countless men in South Vietnamese military garb getting off provincial buses, having made their way back from the battlefields after their units had been broken apart and scattered.

For the first time in my life, I truly saw fear in someone’s eyes when I spoke to a female relative of an FSO in Washington who had asked me to check on his Vietnamese family. She asked what was to become of them and who would help them escape. Other Vietnamese begged me to take their babies or small children out of the country. At the embassy, several longtime colleagues asked me if I would carry some of their most precious personal possessions out on our plane.

My conversations with two Cabinet ministers and a contact in the prime minister’s office made the situation seem even more desperate. In whispered tones, I was told that Pres. Thieu was paralyzed by fear, unable to make a decision, and that expectations of leadership from Independence Palace were nil.

Just a Matter of Time

But it was during my visit with the young Defense Department analysts in the “tank” at the old MACV headquarters that I came to realize that the situation was truly hopeless. There I was able to track on large briefing maps the unobstructed movement of North Vietnamese divisions down the Ho Chi Minh Trail and into the southern battlefields. More than anything else, that stark display of the order of battle showed just how badly outnumbered the South was in terms of main force divisions—almost two to one. If the North continued its offensive, the inexorable flow of this overwhelming force into the south meant the inevitable defeat of South Vietnam.

Arriving in May 1974, I found the White House beset by the issue that would ultimately play a very significant part in the demise of South Vietnam: Watergate.

One of my most riveting conversations was with Al Francis, who as head of the embassy’s political-military affairs section had often reflected Amb. Martin’s hopeful assessments. He had been consul general in Da Nang when it was overrun just a few days earlier and had escaped on one of the very last flights out. In the chaotic evacuation, he had been controlling the door into the already badly overcrowded U.S. aircraft that was carrying Americans, and some of the Vietnamese most at risk, to safety as the North Vietnamese closed in on the airport.

When one renegade soldier threatened to halt the flight so he could board it, Al had pushed him away. The desperate man pulled out a handgun and fired at almost point-blank range toward Al’s face. The bullet left a blackened, curved indentation burned deep into his neck but, miraculously, did not penetrate the skin. He was left with a highly visible scar and a traumatized demeanor. To me, it was a harbinger of what was to come. It was clear that Al now saw the ominous future clearly, even if the ambassador did not.

When I returned to the residence that evening, I wanted to convey to Amb. Martin the hopelessness of the situation as I saw it and the need for urgent planning for an evacuation. The challenge, however, was to do this without losing his ear. The ambassador's reputation was that as soon as he determined that an officer or adviser was a naysayer or had negative views of the situation, he immediately tuned them out. As I endeavored to share my observations, he started to drift away. I could not be sure how much of anything I said actually got through to him.

But from my review of the daily embassy cables, it was evident that, while considered extremely serious, the situation was not being reported as hopeless. As a result, there was no missionwide preliminary planning for an evacuation. This differed markedly from my own judgment that the end could come in a matter of weeks, depending on how quickly North Vietnamese troops would reach Saigon.

Time for a Reality Check

The author acts as interpreter for Ambassador Leonard Woodcock in a meeting with North Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Van Dong in Hanoi, March 1977.

Courtesy of Kenneth Quinn

I did three things while in Saigon to try to address these divergent perceptions.

First, I made daily phone calls back to Washington to brief my boss at the National Security Council, Bill Stearman. To his great credit, Bill intervened during the Washington Special Action Group sessions (chaired by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger) to interject my much more pessimistic assessment as a counterpoint to the official reporting.

My second step was to seek a private session with Gen. Weyand, during which I painted the picture for him that I had found in terms of the collapse of confidence in Pres. Thieu’s administration, the sense of national despair permeating the civilian and military population and the stark military situation. The general, with whom I had worked from 1971 to 1972 at MACV headquarters, did not disagree with any part of my analysis, and sighed audibly when I mentioned the potential three-week timeframe before the South’s complete defeat.

Finally, I tried to put in place a mechanism that would allow at least some endangered Vietnamese to be evacuated as the end came. I met with two close friends—FSO Lacy Wright and Frank Snepp, the chief intelligence community analyst at the embassy—and expressed my dismay that no action was being taken, even behind the scenes, to prepare for an evacuation. Since we all had individuals we wanted to rescue (for me that included my wife’s family), I proposed that we create our own secret evacuation plan despite the injunction against any planning in the embassy. Lacy and Frank agreed, and we sketched out a safe house system and basic communication plan with phone numbers that could be shared with those Vietnamese we wished to help.

Lacy and I then began making contacts around Saigon. Once back in Washington, I sent dozens and dozens of additional names of relatives, friends and official contacts of State and USAID officers who were now living in the United States, including those from a large group of FSOs who were meeting daily at the department for a similar purpose (story here). Since my office was at the White House, every phone call I made to Saigon went with “flash” precedence, thus ensuring that I always got through and kept the names flowing.

While Gen. Weyand and his most senior advisers called on Pres. Thieu and the top military echelon of the South Vietnamese government, I went off on my own about the city.

A Long Flight Home

The Weyand Mission ended on April 4. On the long flight back to Washington, I drafted my own memoranda to Secretary Kissinger, both on the bleak prospects for South Vietnam and what would be needed to deal with the huge number of refugees—as many as a million people—who could seek to flee the country. Dated April 5, 1975, the two memos spelled out that the South could be lost in as little as three weeks.

By mid-April, even as the NVA moved closer and closer to the capital, Amb. Martin still felt that any sign of evacuation activity by the United States would cause what little remained of the South Vietnamese political and military fabric to completely rend, with mass chaos ensuing.

I feared that if this inaction continued, the opportunity to evacuate at least some Vietnamese would be lost completely. So, one evening, when most of the staff had departed, I walked from my third-floor office in the Old Executive Office Building across West Executive Avenue, in the side door of the White House, and up to Deputy National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft’s office. Always the last person to leave, Brent was engrossed in one of the multiple red-tagged memos that were stacked on what was technically still Henry Kissinger’s desk.

He beckoned me in and, with just the two of us there, I briefed him on the secret evacuation system that we had set up, which now had many high-risk Vietnamese ready to be taken out of the country. I told him that what was needed was a message to the ambassador from the White House instructing him to immediately begin to evacuate these individuals. I handed him a draft cable which gave the details of our plan, with Lacy Wright as the contact.

Kenneth Quinn, right, and his wife, Le Son, center, with former Representative Leonard Boswell (D-Iowa) on Jan. 19, 2009, when Quinn received the Army Air Medal for flying / commanding more than 100 hours of helicopter combat operations in Vietnam in 1970 during his assignment as an FSO to the CORDS program. He is the only civilian to have received this medal.

World Food Prize

General Scowcroft went to the president that night and then sent the message through the White House back channel to Amb. Martin, instructing him to assist these people to leave. This action, in effect, began the flow of Vietnamese out of the country. A trickle at first, over the next week or so more than 100,000 refugees were airlifted out of Vietnam. In his book Decent Interval, Frank Snepp wrote that this system eventually saved thousands of Vietnamese civilians.

One last memory of the evacuation is from April 28. When I arrived at work early that morning, I learned that the NSC had just met and advised the president to halt the evacuation due to the threat of attacks on the airport. When I phoned Saigon to relay this information, however, I was told that Tan Son Nhut Airport was not under attack, and that there were still 20,000 high-risk Vietnamese at the airport whom we were about to abandon.

Wondering what I could possibly do to prevent a humanitarian disaster, I ran across to the White House and into David Kennerly’s ground-floor office. Out of breath, I explained the desperate nature of the situation. David reacted instinctively. He dashed up to the Oval Office, to which he always had access, and told the president directly that he had an absolutely reliable source who told him there were thousands of refugees stranded at the airport who could still be saved. The president, who was said to consider Kennerly like a son, acted immediately to order the evacuation to continue. Thousands more refugees were flown out of the country that day, until the North Vietnamese bombardment finally forced the airport to close.

The evacuation of the embassy was completed on April 29. The next day, a North Vietnamese tank crashed through the gates of Independence Palace, ending the war and the existence of the Republic of Vietnam. Hoa Binh—peace—had arrived, but few in the South were dancing to welcome it the way my employees in Chau Doc had on Jan. 27, 1973.

Read More...

- Of Ladders and Letters— On the anniversary of Saigon's fall, a trove of documents sheds new light on old traumas (TIME, April 24, 2000)

- National Security Adviser’s Presidential Correspondence with Foreign Leaders Collection: Cambodia - President Lon Nol (Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum)

- Foreign Relations of the United States: Vietnam, January 1973-July 1975 (Department of State, Office of the Historian, Sept. 2010)

- Integrity and Openness: Requirements for an Effective Foreign Service | Kenneth Quinn (The Foreign Service Journal, Sept. 2014)