Mobilizing for South Vietnam’s Last Days

At the State Department, a small group of FSOs worked outside normal channels to prevent a potential human tragedy.

BY PARKER W. BORG

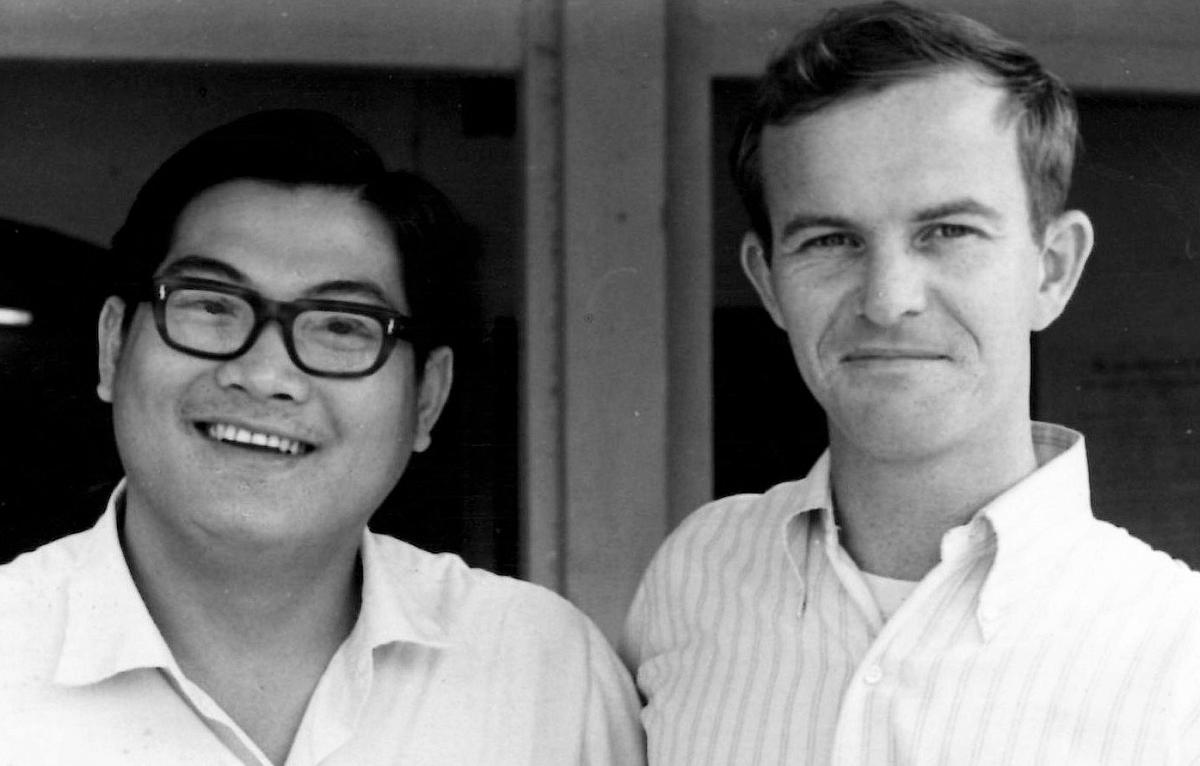

Parker Borg, at right, with one of his counterparts in Bing Dinh, circa 1969

Courtesy of P. Borg

Images of the final days of the American presence in South Vietnam 40 years ago remain vivid in the minds of everyone who lived through those turbulent years, or saw last year’s documentary, “Last Days in Vietnam.” Less is known, however, about what was happening then at the Department of State.

In addition to what history books have recorded about the role of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, a small group of Foreign Service personnel without responsibilities for Vietnam began working outside normal channels to address the end game there. Their success illustrates what’s possible when a small, determined group mobilizes to deal with a crisis.

When North Vietnamese forces took the town of Ban Me Thuot in March 1975, many of us who had previously served at Embassy Saigon or in the provinces believed South Vietnam’s end was just around the corner. Yet EAP seemed preoccupied with efforts to obtain supplemental funds from Congress to support past commitments to Vietnam, while our ambassador in Saigon, Graham Martin, was focused on keeping the country together and was unwilling to consider any form of evacuation.

Ambassador Martin argued that even contingency planning would undermine the confidence of South Vietnamese authorities, triggering the very crisis we were trying to avoid. We remained convinced, however, that the potential human tragedy from the collapse made planning essential. This was our primary concern.

Operating Below the Radar

Working in offices where we had access to some cables and intelligence reports but, with one exception, no Vietnam responsibilities, a small group of us who had all served there began meeting every day at lunch to talk about the deteriorating situation. These below-the-radar meetings took place in Deputy Secretary of State Robert Ingersoll’s conference room.

The core group included Frank Wisner (Director for Management in Public Affairs), Paul Hare (Deputy Director of Press Relations), Craig Johnstone (Director of the Secretariat Staff), Lionel Rosenblatt (on the Deputy Secretary’s staff), Jim Bullington (who worked on the Vietnam desk and could keep us informed about desk-level actions) and myself (who had been working on Secretary Kissinger’s staff). We were joined on occasion by one or two others.

The group worked at two levels. EAP Assistant Secretary Philip Habib accepted our offer to work on issues the bureau was too busy to cover. Deputy Secretary Ingersoll supported us by issuing occasional tasking requests, which permitted us to draft action papers.

Reviewing the embassy’s evacuation plan, we found it woefully inadequate for the thousands of American citizens living throughout the country. In addition, we believed that the United States had an obligation to large numbers of Vietnamese who had worked with Americans over the years and would be endangered under a communist regime.

These were the days before State routinely set up task forces the moment a crisis emerged.

We estimated that an evacuation plan for Vietnam needed to cover about 6,000 Americans, 4,000 other foreigners (ceasefire observers from the 1973 accords, foreign diplomats and third-country nationals working for the United States), and anywhere from 100,000 to one million Vietnamese. We developed information about commercial aircraft and ships in the area, consulted with Pentagon officials about military evacuation assets and sent forward various evacuation scenarios.

As North Vietnamese troops got closer to the capital in April 1975, the Federal Aviation Administration wanted to close the airport to commercial traffic. We pushed it to keep the airport open and called commercial airlines to increase the number of flights into Saigon.

The end seemed near, but nobody had any idea about Hanoi’s intentions, how long the South Vietnamese would resist or how violent the last days might be. Amb. Martin continued to oppose planning an orderly departure for American personnel or considering any evacuation for the many Vietnamese who had been associated with the U.S. effort.

His concern was certainly understandable: the Vietnamese numbers were staggering and the implications dramatic. Our figures showed 164,000 current embassy employees and family members, 850,000 former employees and family members, 93,000 close relatives of U.S. citizens, and 600,000 military and civilian officials who likely had close ties to Americans.

Organizing a Task Force

Our second major concern was how Washington organized itself for the end game. These were the days before State routinely set up task forces the moment a crisis emerged. We wanted to keep the department at the center of operations, but argued for an interagency task force that included representatives from the Defense Department, the Central Intelligence Agency and various domestic agencies. State agreed to establish an in-house task force, but we kept pressing for it to be an interagency operation to deal with the huge influx of Vietnamese refugees we anticipated would follow the collapse.

On April 18, 1975, the special Inter-agency Task Force was established under the leadership of Ambassador L. Dean Brown, a former deputy under secretary for management. We approached Amb. Brown immediately and volunteered to take leave from our jobs to become his core staff. Key members from other agencies who joined the task force staff at the beginning were Julia Taft from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (now Health and Human Services), Clay McManaway from the CIA and Colonel Gerald Rose from DOD, all of whom eventually moved on to other jobs at State.

At about the same time, Amb. Martin finally agreed to an orderly evacuation of Americans and top Vietnamese officials, but adamantly opposed any evacuation planning for other Vietnamese. He suggested they head for designated points along the coast where American ships would “try” to pick them up.

The ambassador’s attitude irritated most of us, but two task force members, Lionel Rosenblatt and Craig Johnstone, decided to take direct action. Without informing anyone, they flew off to Saigon on April 19 to implement their private evacuation plan. En route, Lionel called me to explain that he would call each day, using a pseudonym—to verify his well-being—and provide a status report. Since the task force was in a fluid state during these first days, it took two or three days before their absences were noted.

Amb. Martin was furious when he learned that two FSOs had returned to Vietnam during the draw-down for an unidentified mission. He sent a blistering message demanding their recall and ordered staff members to locate them. In the frenzy of Saigon’s last days, the two stashed some 200 Vietnamese former work colleagues in vehicles, slipped them past Vietnamese security and pushed them aboard departing aircraft.

The two errant task force members escaped from Vietnam just days before the end. Once they had left, members of the informal group convinced Amb. Brown that the two should not be disciplined, but welcomed back and their experiences put to use. Others in the department disagreed, however. Eventually, they were summoned to meet with Sec. Kissinger to consider charges of insubordination; but he acknowledged their bravery and declined to pursue any course of discipline.

Helping Vietnamese Refugees

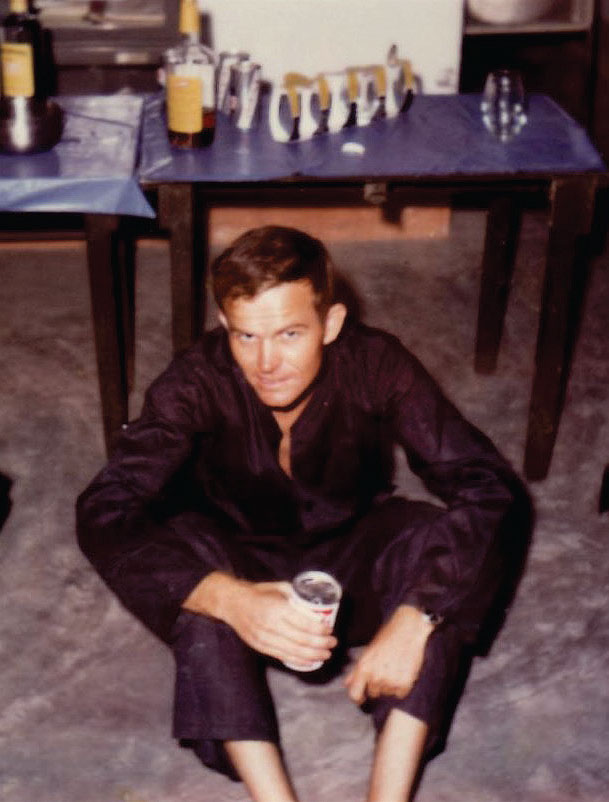

Parker Borg relaxing at a social event in Binh Dinh, circa 1969.

Courtesy of Parker Borg

Chartered U.S. aircraft began making hourly flights out of Saigon on April 22. In addition to Americans and third-country nationals, the planes carried away any Vietnamese who could make it past the gauntlet of security barricades between Saigon and the airport set up by the local authorities to stem panic. The final chaos was beginning.

With the North Vietnamese army poised to enter the capital, we were uncertain whether they intended a violent takeover or would permit an orderly departure of the last Americans. On April 29, President Gerald Ford gave the order to evacuate the embassy by helicopter, setting off the dramatic final hours of the American presence in Vietnam. We monitored the evacuation from our seventh-floor task force office as best we could, given the primitive communications that existed 40 years ago.

The flights were supposed to end at midnight Saigon time, but continued for three more hours under orders from a heroic Amb. Martin. About 1,000 Americans and 6,000 Vietnamese departed the embassy roof during the final 14-hour liftoff. The North Vietnamese held their fire as the waves of helicopters followed the Saigon River to U.S. naval vessels just offshore.

Once the evacuation was underway, a new set of issues confronted our task force. What would be the destination for the refugees leaving Vietnam? The airlifted refugees went from ships to U.S. bases in the Philippines, and later to other bases on Wake Island and Guam. Simultaneously, thousands of other Vietnamese fled on private boats to neighboring countries, many of which were hostile to them. This required a wave of diplomatic efforts to permit their entrance, at least on a temporary basis.

Then, where would the refugees go from the temporary staging points? It was understood that some would come to the United States, but how many? Where would they stay until resettlement was arranged? Working with the Defense Department, each service agreed to open portions of one base. The Navy provided Camp Pendleton in California; the Army, Fort Chafee in Arkansas; and the Air Force offered Eglin Base in Florida. When Eglin proved too small, the Army opened an additional camp at Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania.

By early June 1975, about 130,000 Vietnamese refugees were under American control: 56,000 were in the United States, 44,000 were at bases outside the country and 30,000 had already been released from the system. In addition to daily maintenance, the camps needed to provide medical screening, immigration processing and counseling about life in the United States. Concurrently, we pushed a worldwide appeal to other countries through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Red Cross and the Intergovernmental Committee on European Migration, to establish resettlement programs elsewhere to welcome Vietnamese refugees.

The ambassador’s attitude irritated most of us, but two task force members, Lionel Rosenblatt and Craig Johnstone, decided to take direct action.

Everything Happened So Quickly

To organize the settlement of refugees in the United States, we promptly began holding meetings with a half-dozen voluntary agencies whose work in this field dated back to World War II. These included the International Rescue Committee, Church World Services, Catholic Relief Services and Lutheran World Services. We also contacted local community organizations to facilitate sponsorship and resettlement. We helped all these organizations set up offices at the military camps, which many of us visited to monitor conditions and programs.

In the weeks following South Vietnam’s collapse, State proposed legislation (drafted by our task force), testified on its behalf before both houses of Congress, and witnessed Pres. Ford signing into law the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975. This authorized $405 million for costs relating to the reception centers, resettlement support, medical and welfare services, and the movement of some refugees to third countries. It was also the beginning of what would become the largest refugee resettlement program in the United States since the end of World War II.

Everything happened so quickly in the spring of 1975 that it was hard to tell when one activity ended and the next began. Within two months our task force oversaw the evacuation of Vietnam, established restaging camps, developed sponsorship programs, obtained legislative authorities, began resettling thousands of refugees in the States and promoted the resettlement of thousands of others in third countries.

While all of us on the task force brought our individual knowledge and commitment to its work, events on the ground quickly brought the entire department, and federal government, together to accomplish our goals. But the bottom line was the personal satisfaction we all derived from making a difference on an important national issue.

Read More...

- Ambassador Parker W. Borg Oral History Interview with ADST (Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training)

- Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975 (www.immigrationinamerica.org)

- America in Vietnam: The Final Act (Dr. John Guilmartin)

- The President’s Advisory Committee on Refugees: Interagency Task Force, May 19, 1975 (Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library)