Finding My Heroes, Finding Myself: From Refugee Child to State Department Official

Amidst the chaos of the last days in Saigon, U.S. government personnel risked their lives to save Vietnamese.

BY ANNE D. PHAM

With the fall of Saigon inevitable, at-risk Vietnamese climb aboard a barge in Khanh Hoi Saigon Port on the afternoon of April 29, 1975. Joe Gettier, with the help of Mel Chatman and Bill Egan, and against the orders of the U.S. ambassador, left the embassy that day to save people, using barges pulled by tug boats.

Nik Wheeler

My journey to America began 40 years ago, when I was plucked out of the Pacific Ocean during the last days of the Vietnam War. While that tumultuous period is fraught with tragedy, there were also many instances of hope and heroism. Indeed, I would not be where I am today were it not for the courage, kindness and compassion of countless personnel from the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development, members of the military and others who risked their lives to save endangered Vietnamese amidst the war’s chaotic denouement.

The war in Vietnam was a hot conflict that had emerged from the Cold War global confrontation between the superpowers. It was a war by proxy: China and the Soviet Union funded Communist North Vietnam, while the United States supported South Vietnam and served as its key ally. Canada, Australia, South Korea, Philippines and Japan also assisted with various aspects of the U.S.-led effort.

Many South Vietnamese, my father among them, had worked in various capacities in support of the American effort to ensure the freedom and independence of the Republic of Vietnam, a democratic country. Such individuals were at grave risk as North Vietnamese communist forces advanced, yet the U.S. was concerned about the appearance of abandonment that could come with overt evacuation planning. Nevertheless, many American civilian and military personnel scrambled to save the lives of these endangered individuals, sometimes defying orders from their superiors and disregarding their own safety to follow their conscience.

It was at this point that brave individuals like USAID officers Joseph Gettier and Mel Chatman sought alternative, last-ditch means to rescue people.

Among them were Foreign Service officers Lionel Rosenblatt and L. Craig Johnstone, who brought attention to the need for evacuation of South Vietnamese employees and associates at risk. After being denied permission to go to Saigon in the spring of 1975, these young diplomats took personal leave, purchased tickets with their own resources and saved several hundred people. Other FSOs, such as Ken Moorefield and Lacy Wright, also made significant efforts to gather people from various locations throughout the city.

15 Minutes to Flee

My father, Joseph Thinh Pham, came home on the evening of April 29, 1975, and told my mother that we needed to flee for our lives. He had just learned from an American at his workplace that the airport was under rocket fire, and that most roads in and out of Saigon were closed due to the fighting that would soon envelop the capital. The day before, he had witnessed smoke billowing from the USAID compound on the northern edge of Saigon.

This would not be the first time my parents had abandoned the life they knew. In 1954, when the country was partitioned, leaving the North under communist authoritarian rule and the South under a nascent democratic government, many Catholics, including my parents, fearing religious persecution, fled south.

Twenty-five years later, my parents again frantically packed up clothes, family photos and music tapes to help us remember our cultural identity. Sadly, we had to leave our two dogs behind.

I remember my father recounting, in vivid detail, the story of how we left Vietnam, saying that he wondered who the young Americans were who had helped to save our family and so many others.

The original evacuation plan for Americans and those South Vietnamese thought to be at risk depended on the assumption that it would be possible to continue flights from the Tan Son Nhut Airport near Saigon and make use of a limited number of helicopter airlifts from the embassy compound. The North Vietnamese rocket fire on the airport, which left the runways inoperable, created a dire situation.

It was at this point that brave individuals like USAID officers Joseph Gettier and Mel Chatman sought alternative, last-ditch means to rescue people. They commandeered military transport barges that had been used to carry supplies during the war. The two young Americans, both fluent Vietnamese-speakers, instructed the evacuees to board those vessels in the port.

American military personnel help refugees, including 3-year-old Anne Pham, off a plane at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, in May 1975.

U.S. Army

That was how my parents left their homeland with their six young children. Our escape down the Saigon River, with darkness setting in, was a dangerous one. Near Vung Tau Harbor, where the river opens to the Pacific Ocean, we came under rocket fire. Thankfully, as I was only 3 years old, I have only faint memories of the journey. As the barge drifted out to sea, crammed with refugees, my father held me close and solemnly said to my eldest brother: “Take a good look at your country. It will be the last time you see it.”

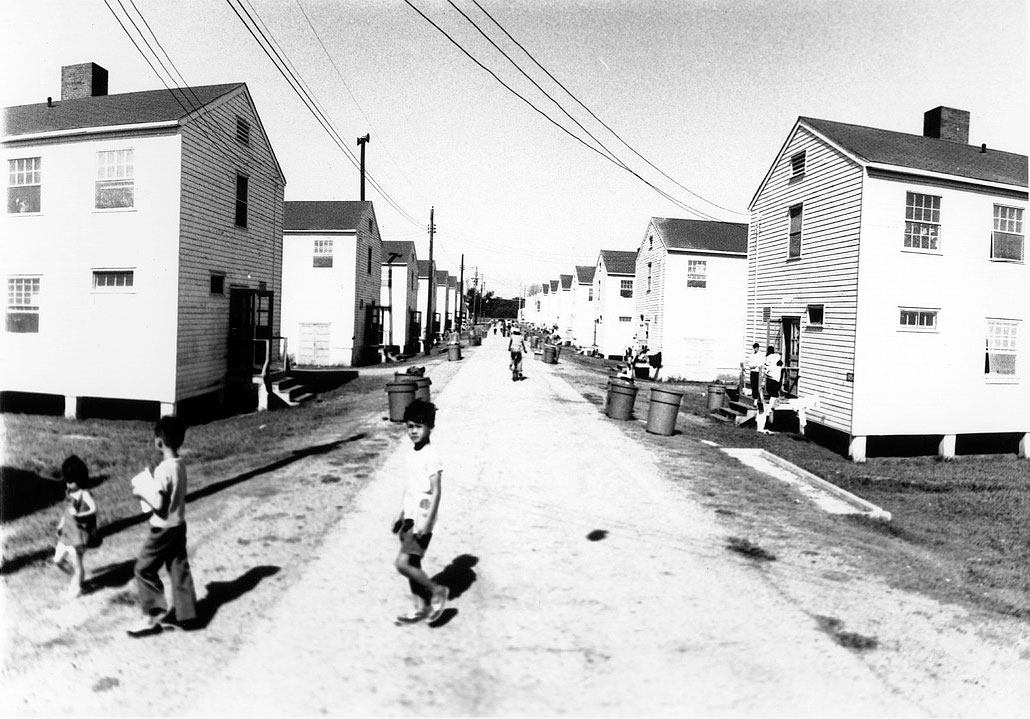

The next day, we were plucked out of the ocean from our barge and boarded the U.S.S. Sgt. Andrew Miller. On the evening of May 2, 1975, the flotilla was directed to the U.S. naval base at Subic Bay, in the Philippines. We were then transferred to Guam, and onward to Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, one of several refugee camps that had been set up to process the influx of refugees from Vietnam and its war-torn Indochinese neighbors. Our helpers at this stage included Richard Armitage, then a young naval officer who would eventually become Deputy Secretary of State.

There were many volunteers who helped us learn English and skills for resettlement and assimilation into American life. Among them was Phyllis Oakley, with whom I later worked when she was a press officer in the State Department’s public affairs office. Another FSO, Theresa Tull, who would later become the first female U.S. ambassador to Brunei, cared for many children, including personally caring for the young children of General Ngo Quang Truong, who stayed behind because he did not want to abandon his troops. Others, like Frank Miller, flew in from neighboring countries as early as March to secretly rescue people.

From my father and his South Vietnamese contemporaries I learned that it is important to deeply understand the perspectives of both friends and adversaries.

Resettlement and the Gift of Hope

Growing up in the small New England town of Amherst, Massachusetts, was a stark contrast to living in the tropical heat of Saigon, where I was born. The local people and church in Amherst were welcoming and embracing, giving us clothes and other items to make us feel at home.

Seeing snowfall for the first time was exciting! But in a sad reminder of the life we had left behind, I kept asking my father to take me to see the “big turtles.” Still a young child, I could not grasp that they were in Saigon, at the zoo we had often visited before our departure. My father had to tell me that they were now a beautiful memory to cherish, for we had lost our country.

I remember my father recounting, in vivid detail, the story of how we left Vietnam, saying that he wondered who the young Americans were who had helped to save our family and so many others. He wanted to find them and say thanks—for the freedom we have and for the fact that we are alive. Yet while my parents were, understandably, stuck in the past, America was putting the Vietnam War behind it. Indeed, that process likely began years earlier, with the withdrawal of all U.S. troops in 1973 following the Paris Peace Accords.

The Pham family was sponsored by a local church and Professor Lucien Miller of the University of Massachusetts. In July 1975, from left to right, in the backyard of their sponsor’s home, where they stayed: Don, Maria Cuc (Grandma), Theresa, Paul, Mary (mother), Joseph (father) holding Anne, Tony and John.

Andrew Marx / Amherst Record Newspaper

As a student from a bicultural background in a small college town, I felt this tension between the past and the present throughout elementary and high school. When the topic of the war or “Vietnam” came up, there seemed to be a negative connotation, a sense of shame and a lack of desire for discussion. It seemed that many wanted to forget the war and the graphic television footage of death and destruction that had been its hallmark. At home, my father continued to recount stories as we ate my mom’s homemade pho soup while prewar romantic love songs played in the background.

While the war remained divisive for Americans, there was bipartisan support for assisting refugees in the years immediately following it. Senator Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) had long been interested in refugee issues. According to Assistant Secretary of State for Population, Refugees and Migration Anne C. Richard, “He became the author and driving force behind the Refugee Act of 1980, which moved the country from an ad hoc program to bring refugees to the U.S. to a formal partnership between the government and private organizations with annual goals for refugee admissions.” Others, like Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.), have also played an instrumental role in supporting humanitarian programs to reunite families and provide assistance for those who were released from re-education camps.

With congressional refugee admission authorities and funding, Julia Taft, Shep Lowman, Lionel Rosenblatt, Hank Cushing and other FSOs began implementing one of the largest refugee resettlement programs in the world, including approximately 140,000 refugees who arrived in 1975. Forty years later, they and other waves of refugees have made important contributions to America and other countries—far from the burden that many predicted.

Normalizing U.S. Vietnam Relations: Preparing for a New Future

In 1995, I could sense these solemn sentiments of loss and sadness among the Americans in attendance with the late Secretary of State Warren Christopher at Noi Bai Airport in Hanoi for a ceremony attending the repatriation of American remains. I was among the State Department personnel who assisted with Sec. Christopher’s trip to normalize relations with Hanoi and establish a new embassy at President Bill Clinton’s initiative.

Young officers with the interagency team help transfer endangered refugees from a barge on to a U.S. Navy ship on April 30, 1975. The Phams’ barge underwent menacing rocket fire near Vung Tau harbor, with nearby boats exploding as they were hit.

U.S. Navy Archives

I thought about the 58,000 American service members who had died in the Vietnam conflict. I also could not help but think about those in my father’s generation—the more than one million courageous and committed South Vietnamese military and civilian officers who died during the war, were sent to concentration camps or were executed. Then there were the subsequent waves of “boat people” who perished in the ocean—nearly half a million by some estimates. The war had continued to take a human toll long after the fighting was over.

While helping the press delegation, I sensed the energy of the younger generation of Vietnamese, eager to learn and yearning for a prosperous future. The country was changing and had moved on from the war years. Then again, many of them were too young to even remember the war.

In fact, the entire Asia-Pacific region was transforming, with increased trade and commerce and greater participation in regional organizations such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. The international context and the regional dynamics had shifted with the formal end of the Cold War and demise of the Soviet Union. Walking by the tranquil Hoan Kiem Lake in Hanoi, I saw turtles and recalled those I’d seen at the zoo as a child. Symbolic of the dynamics of Southeast Asia, there was continuity and change all at once.

As Secretary of State John Kerry wrote in his Feb. 2 op-ed, “From Swift Boat to a Sustainable Mekong,” in Foreign Policy magazine: “Long ago, those waterways of war became waters of peace and commerce—the United States and Vietnam are in the 20th year of a flourishing friendship.” As U.S. Ambassador Ted Osius noted in his arrival in Ho Chi Minh City in February, “A Vietnam that is strong, prosperous and independent, and that respects rule of law and human rights, was, is and will be an indispensable friend of the United States.”

Seeking Clarity, Healing and Heroes

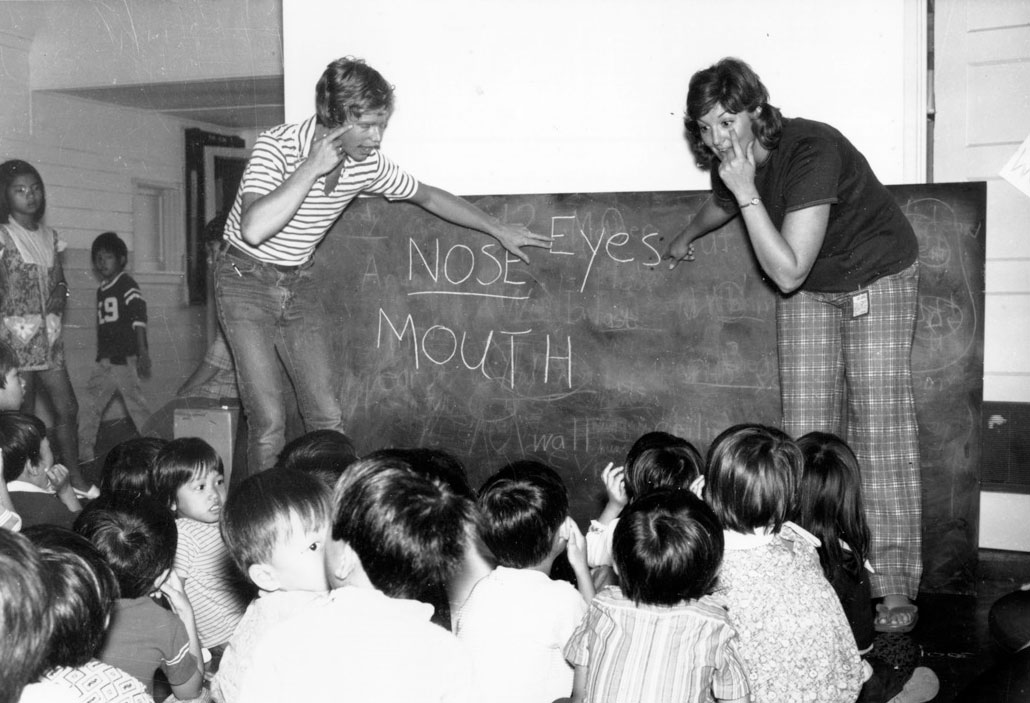

State Department officers, like Phyllis Young, at right, help teach refugee children at the Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, refugee camp.

U.S. Army

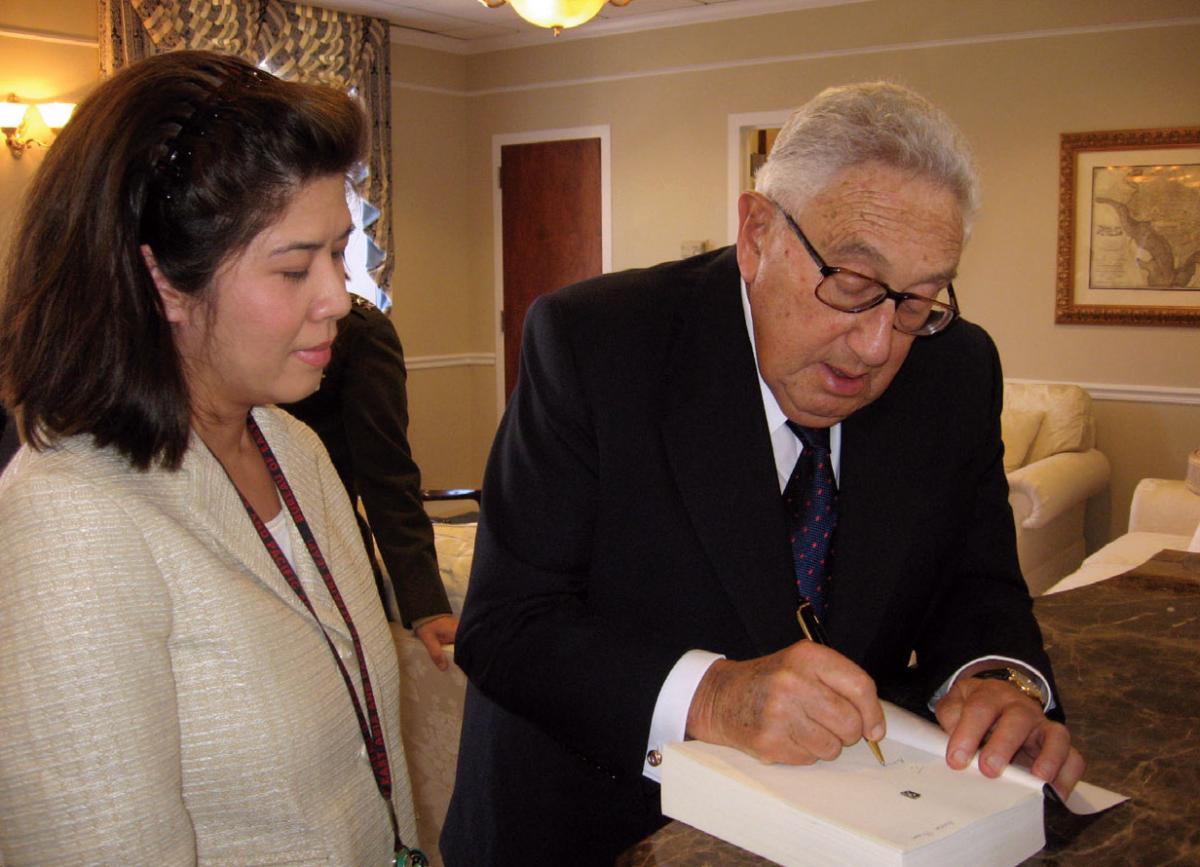

When I attended the National War College in 2008, I had an opportunity to meet Henry Kissinger, who said to me, with great emotion: “Out of my entire career, Vietnam and how the war ended pained me the most.” I asked Dr. Kissinger what lesson he learned from Vietnam, and he said: “We should not start a war we cannot finish. No war should end in stalemate.”

I gained a bit more insight in 2009 from a conversation with former Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte, who had worked on the Paris Peace talks under then-National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger. Ambassador Negroponte expressed the sentiment that negotiations had been conducted in haste and that perhaps a better peace settlement could have been achieved—with better protections for America’s South Vietnam ally—if there had been greater patience and care. What astonished me most was his bravery. As a young FSO at that time, he had articulated his concerns to Kissinger, that settling on final terms in four days, without adequate consultation with the government of South Vietnam, would lead to a very unfortunate outcome for that country.

A sign at the entrance to the Fort Chaffee refugee camp indicates the number of refugees housed there.

U.S. Army

That same year, I met Tony Lake, who in 1969 had become special assistant to Henry Kissinger. He expressed the sentiment that if the intent was to end the war from the time the secret negotiations commenced in the late 1960s, there was a moral imperative to do so earlier, so that more lives not be lost. Lake went to Vietnam as a young FSO from 1963 to 1965, but then resigned from the Foreign Service in protest over the war. He later became national security advisor in the Clinton administration.

After these exchanges, I recognized that it is easier to surmise what factors may have resulted in a different outcome in hindsight. To me, the answers appeared to be just as elusive as the insurgents the United States and its Republic of Vietnam allies were trying to track down in the jungles of Southeast Asia. I am hopeful that as documents and sources become available from many countries, reassessment of the war and additional key lessons may come to light as historians continue to battle it out, hopefully with greater balance, objectivity and clarity than in previous decades.

A Healing Effort

Anne Pham plays with her brothers, John and Tony, at Fort Chaffee refugee camp in June 1975.

U.S. Army

Later, while I was serving on the faculty of the Industrial College of the Armed Forces teaching grand strategy and national security studies, military officers asked me about how I came to this country. This prompted me to search for some of the individuals who were there during the last days of the war, to share their lessons with the military and civilian students I had the honor of teaching.

I invited my “unsung heroes” to a luncheon ceremony in 2009 at the National Defense University, where then-PRM Assistant Secretary Eric Schwartz commended their humanitarian acts. It was a moving, healing reunion that also allowed a daughter to fulfill one of her father’s wishes: to find the brave young Americans who had saved us to express our gratitude and reconnect threads from the past—a Vietnamese cultural tradition. I told them that despite the controversies and outcome of the Vietnam War, nothing should diminish our memories of their heroic efforts to save lives.

From my father and his South Vietnamese contemporaries I learned that it is important to deeply understand the perspectives of both friends and adversaries, recognize early on when ineffective strategies and tactics are applied and make modifications with changing circumstances because it was a complex war. U.S. patience is also essential: it takes time for democracy to develop and deepen. South Vietnam had been confronting many challenges, trying to unify factions as a nascent, imperfect and evolving democracy and a newly sovereign nation. Having cultural sensitivities and respect for our allies, as well as honoring commitments, is important for American leadership and credibility in the long term.

Meeting my heroes has taught me there is always hope, even during the darkest hours of our lives.

These lessons continue to resonate today in as much as questions pertaining to moral considerations in foreign policy and risk-mitigation in ending wars persist.

Diplomats are often at risk during conflicts, but especially so when wars are ending and new power brokers jockey into positions of authority. It is often during such transitions that the environment becomes most dangerous because military involvement has been withdrawn or ramped down significantly, while nation-building efforts must continue, requiring that American advisers, USAID workers and State Department staff remain on the ground.

Anne Pham, State Department faculty member at the National Defense University, honors her 1975 evacuation hero, Shep Lowman, in December 2009. Foreign Service Officer Lowman was first posted to Vietnam in 1966; he returned in 1974 and saved thousands of lives during the last days of the war.

Katie Lewis

The risks in Vietnam were compounded by the fact that there were presidential commitments to aid South Vietnam, as outlined in the Jan. 17, 1973, Nixon letter: “The freedom and independence of the Republic of Vietnam remains a paramount objective of American foreign policy,” and “The U.S. will react vigorously to violations to the agreement.” But, according to Admiral Elmo Zumwalt Jr., former chief of naval operations, they were never communicated to the U.S. Congress and the commitments were not honored. The Vietnam experience also demonstrated the importance of executive-legislative relations. It is challenging for democracies to continue protracted conflicts without support from lawmakers—clear communications and transparency are essential.

As film director Rory Kennedy emphasized during the Sundance launch of the documentary “Last Days in Vietnam” I attended last year, it is important to think carefully about a strategy for ending wars in a responsible manner and mitigate risks to those who helped America as well as innocent civilians caught in the crosshairs. Kennedy’s Oscar-nominated documentary covers the final hours’ efforts to save lives and the story of those left behind. As Colonel Stuart Herrington, who was on one of the last helicopters from the Embassy Saigon in 1975, notes, “Sometimes there’s an issue not of legal and illegal, but of right or wrong.”

Not everyone was saved though, including more than 400 evacuees left inside the U.S. embassy compound. When a number of my evacuation heroes have expressed sorrow for being unable to save more lives and for breaking promises because of orders from Washington to call off the evacuation prematurely, I asked them to think of me and focus on all the lives they did save and what it has meant for us.

The Strength of America

We cannot change the past, but we must never forget the humanitarian acts that show the importance of the State Department’s work. One of the main reasons I wanted to pursue a career in foreign affairs is because I know firsthand the human toll and devastation of war. I recently found my refugee documentation and have made a copy to carry in my handbag, to remind me of how fortunate I am and how I must continue to find ways to do meaningful things for others. It is my hope that future history books about the Vietnam War will include the stories of the brave unsung heroes who followed their conscience and saved so many lives.

President Barack Obama’s May 28, 2012, remarks at the Vietnam War Memorial underscored this notion of making peace with the past that resonated with my father and some of the 1975 evacuation heroes in attendance: “As any wound heals, the tissue around it becomes tougher, stronger than before. Five decades removed from a time of division among Americans, this anniversary can remind us of what we share as Americans. That includes honoring our Vietnam veterans by never forgetting the valuable lessons of that war.”

A healing moment: As a State Department National War College student in April 2008, former refugee child Anne Pham has a special exchange with Henry Kissinger. Dr. Kissinger was both Secretary of State and National Security Advisor during the final years of the Vietnam War.

Francisco Gonzales

Meeting my heroes has taught me there is always hope, even during the darkest hours of our lives, and that we have to keep moving despite adversity. By saving me on that fateful day, they planted the seeds of strength and hope that helped me to achieve my dream of working for the State Department.

My hope is to someday represent America abroad as an ambassador. While I may not achieve this goal, I have learned from my unsung heroes that the journey and our life experiences are what enrich us, more than any destination. We must try even when the odds of success may not be high, like finding a way out of Saigon in April 1975. I want to do it for my 1975 evacuation heroes, to make their sacrifices even more meaningful.

While I am a product of a painful chapter in history, I am also a product of the greatness of America, with its diverse society, democratic ideals and opportunity for all. Only in America can a former refugee child become a senior adviser working for the same agency as do the Foreign Service officers who saved her. I am a living testament to the importance of humanitarianism, a core and enduring strength of diplomacy. It is the story of America, and the American dream restored.

Read More...

- Refugee Act of 1980, Edward M. Kennedy (Refugee Council USA)

- From a Swift Boat to a Sustainable Mekong, John F. Kerry (Foreign Policy, Feb. 2, 2015)

- U.S. Flag Goes Up In Hanoi As Embassy Is Established (Chicago Tribune, Aug. 6, 1995)

- New US Ambassador arrives in Vietnam, meets President (Thanh Nien News, Dec. 17, 2014)

- Last Days in Vietnam, Academy Award nominee documentary (PBS)

- Remembering the Fall of Saigon and Vietnam’s Mass ‘Boat People’ Exodus (The Daily Beast, April 4, 2014)

- Letters: President Nixon to President Thieu, Jan. 17, 1973 (Nixon Presidential Library and Museum)

- Straddling Different Worlds: The Acculturation of Vietnamese Refugee Children (University of California, Davis)