Vietnam: Endings and Beginnings

Reflections

BY BRUCE A. BEARDSLEY

Having been given initial incoming processing, Vietnamese evacuees line up for resettlement processing by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (now the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service) on Wake Island in May 1975.

The end of one national adventure ushers in the beginning of another. Thus it was for Vietnam, and for me.

April 1975. The little news from Vietnam available at Embassy Kabul was grim. I had arrived in Afghanistan four months earlier, and almost immediately the steady beat of the North Vietnamese Army’s march on Saigon could be heard. Provincial capitals, whole provinces, major cities—they all fell to the onslaught.

I had served in Vietnam for 21/2 years, first in the Army (1965-1966) and later, after language training, as a junior FSO in one of the provinces (1970-1972). With each day’s news my thoughts returned to the green jungles and rice paddies I had known, and especially to the Vietnamese friends and colleagues still there. Were they alive? What were they doing? How had it come to this?

As the ineptitude of the embassy’s response and Washington’s dithering became apparent, I was even more distraught. What could I, or anyone, do? Then, out of the blue, a message: I was to take the next flight east to assist with the evacuation from Vietnam. Unfortunately, the next flight to New Delhi, the first step of the journey, would not depart for two days. In the interim, I put my office in order and tried to relearn a few words of Vietnamese.

Flights and time zones blurred: Delhi, Bangkok, Hong Kong, Guam and, finally, Wake Island. Wake was to receive and shelter the human overflow from Guam, and ultimately the island housed some 12,000 evacuees. Reception arrangements were already underway. The U.S. Immigration Service had a small team in place, and a pair of U.S. Agency for International Development evacuees had been sent there, while the U.S. Air Force shouldered the bulk of the logistical responsibilities.

A crowd watches the U.S. team interview their colleagues to determine resettlement eligibility and priority interviews in Pulau Bidgon, Malaysia, in August 1979. This island held about 45,000 Vietnamese refugees at the peak in 1979.

The USAID guys moved on shortly after my arrival, so I was left with the title “Civil Coordinator” and no staff, no job description and little guidance. The strongest ray of encouragement was the willingness with which the Vietnamese evacuees pitched in to run the camp. Once the basics of food, shelter and medical treatment were organized, I increasingly devoted my time to unique or intractable problems.

Many of those involved families who had left Vietnam together, but had become separated along the way. Another group wanted to return to Vietnam—typically they had been ship or aircraft crew members with no choice about departing. We also had several hundred with relatives in countries other than the United States.

I’ll never forget one person with whom I spent many hours. A very nice fellow, he had been a ranger captain and aide to a senior South Vietnamese general. In late April the general had taken him on a reconnaissance flight; but instead of flying over the battlefield, without warning the general ordered his chopper out to sea to join the many helicopters landing on vessels of the U.S. Seventh Fleet. My new friend told me his U.S. contacts had assured him they would see to his family’s safe evacuation when the time came. Alas, they hadn’t.

I sent inquiries to all refugee processing camps, but only received negative replies. My friend insisted he be allowed to return to Vietnam, as he could not imagine life without his family. We could not know what would happen there, but many feared there would be a bloodbath. I told him his rank and position practically guaranteed that the new government would not allow him even to visit his family. He would be better off going to the United States, with the hope of their joining him later. He was adamant, and as far as I know was among those who eventually returned to Vietnam—and imprisonment.

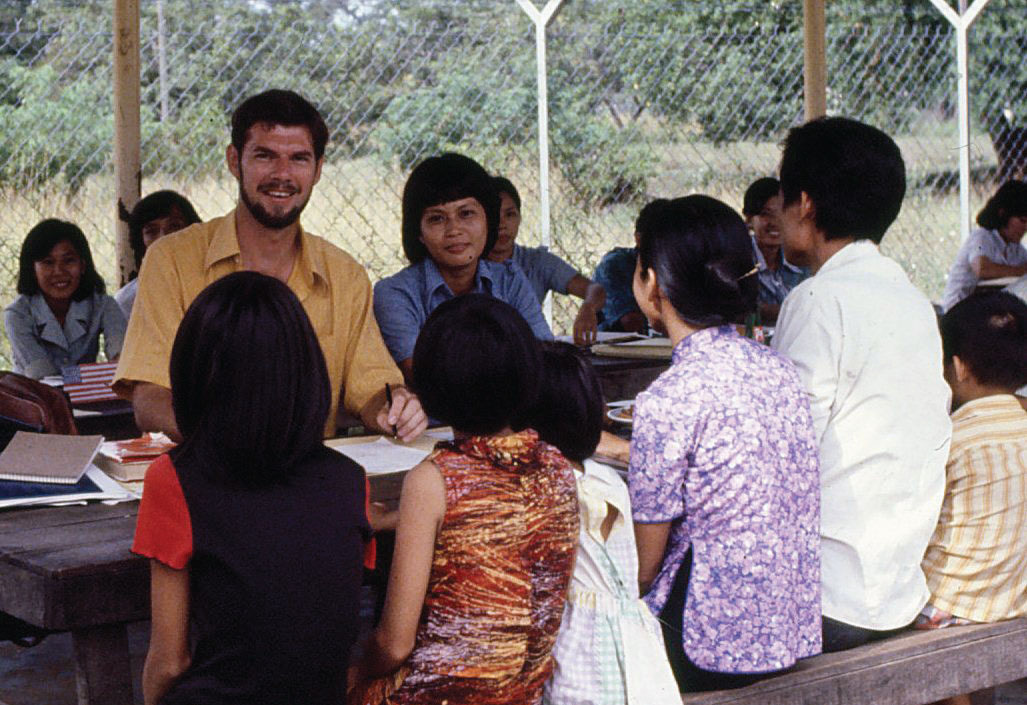

Bruce Beardsley interviews a family for resettlement in Kota Bharu, Malaysia, in September 1979. Though his language ability had returned sufficiently to conduct interviews without an interpreter, he used a volunteer (to his left) to assist with Chinese speakers and to help keep interview notes.

The heartache involved in this captain’s case was in part offset by the hundreds of family reunions I was able to arrange on Wake, a happy result of my cables to Guam and the department. I was also able to get Washington to overturn a decision to indefinitely delay any resettlement from Wake, and enjoyed seeing smiles on the faces of those who were among the first from Wake to resettle in the United States.

After a couple of months, I was medivacked to Clark Air Base in the Philippines, and from there returned to Kabul. I was happy to leave Wake, but remained in contact with a few of the refugees I met there for several years. That experience laid the groundwork for my later refugee work in Malaysia, Thailand and Kosovo.

It is now 40 years since the evacuation, and 50 years since I was among the first U.S. combat troops sent to Vietnam. I still wrestle with the ghosts of Vietnam. My evaluation of our efforts in that war has evolved over the years, but I am still critical of myself and my country. What could I have done better? What should we have done differently?

But life, and the world, move on. I resumed trips to Vietnam in the mid-1980s, and from the first was overwhelmed by the friendly reception I received—not only from officials (who weren’t always that warm), but from the many people on the street with whom I spoke.

Now one of “my” former first-tour officers, Ted Osius, has recently arrived as the U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, something hard to have imagined four decades ago. Even if one era ends on a sour note, another one begins. Let us hope that this will be a better chapter.

Read More...

- Vietnam Memories, Bruce Beardsley (The Foreign Service Journal, March 2013)